Carlos Ortiz: All We Got

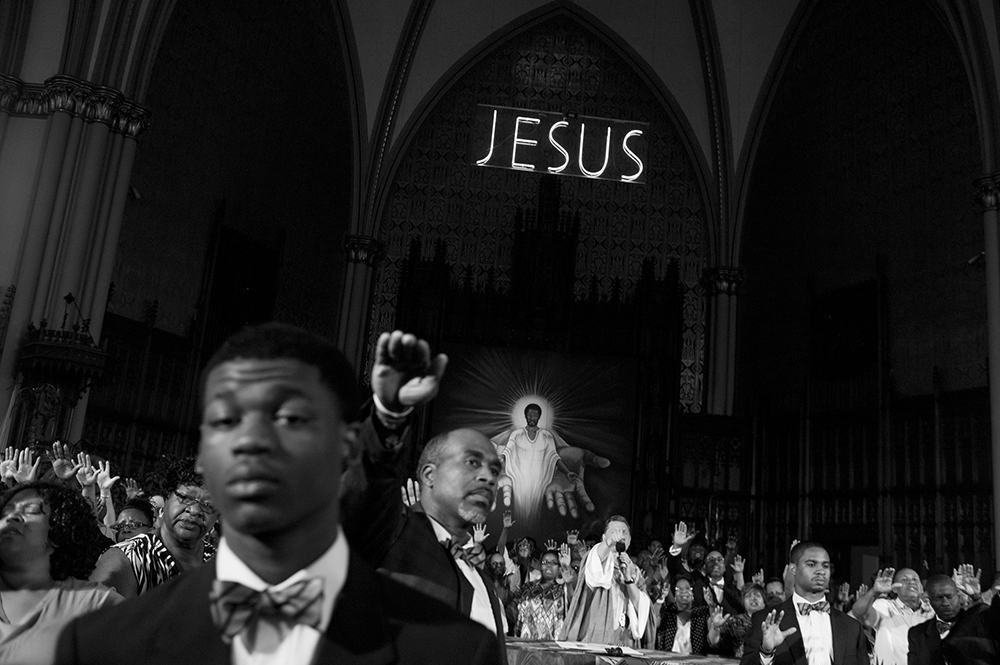

©Carlos Ortiz, Rev. Michael Pfleger of St. Sabina Church embraces young men who are working to break the cycle of violence during a prayer service. Auburn Gresham, Chicago, 2013

Carlos Ortiz and I are united for life as fellow 2016 Guggenheim Fellowship recipients living and working and in the Bay Area. Even before this coincidence, we’d fall into meaningful conversations about photography over stacks of Polaroids he was scanning or the insane quantities of exhibition prints I was making. We are both former Rayko Photo Center Artists-In-Residents and share a belief that a photograph can transport someone toward new perspectives and experiences. Carlos and his wife both teach at the University of California Berkeley, though most of his work is made within African American neighborhoods in Chicago, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and other communities nationwide. He is a documentarian through and through, crossing between film and photography to connect audiences to teen violence and the Great Migration’s lasting legacy.

Carlos Javier Ortiz is a director, cinematographer and documentary photographer who focuses on urban life, gun violence, racism, poverty and marginalized communities. In 2016, Carlos received a Guggenheim Fellowship for film/video. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally in a variety of venues including the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts; the International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, NY; the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago; the Detroit Institute of Arts; and the Library of Congress.

In addition, his photos were used to illustrate Ta-Nehisi Coates’ article The Case for Reparations (2014), which was featured in Atlantic Magazine‘s best selling issue in its history. His photos have also been published in The New Yorker, Mother Jones, among many others.

His film, We All We Got, uses images and sounds to convey a community’s deep sense of loss and resilience in the face of gun violence. We All We Got has been screened at the Tribeca Film Festival, Los Angeles International Film Festival, St. Louis International Film Festival, CURRENTS Santa Fe International New Media Festival, and the Athens International Film + Video Festival.

Carlos’ current project is series of short films chronicling the contemporary stories of Black Americans who came to the North during the Great Migration. Beginning with his mother-in-law’s story, Carlos is exploring the legacy of the Great Migration a century after it began. For Carlos, who moved back and forth between Puerto Rico and the U.S. mainland as a child, the story of displaced people in search of stability and economic opportunity resonates with his own.

Carlos’ work has been supported by many organizations including the University of Chicago Black Metropolis Research Consortium Short-term Fellowship (2015); the Economic Hardship Reporting Project (2015); the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting (2013); the California Endowment National Health Journalism Fellowship (2012); the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation (2011); Open Society Institute Audience Engagement Grant (2011); and the Illinois Arts Council Artist Fellowship Award (2011).

In addition to his photography and film, Carlos Javier has taught at Northwestern University and the University of California, Berkeley. He lives in Chicago and Oakland with his wife and frequent collaborator, Tina K. Sacks, a professor of social welfare at the University of California, Berkeley.

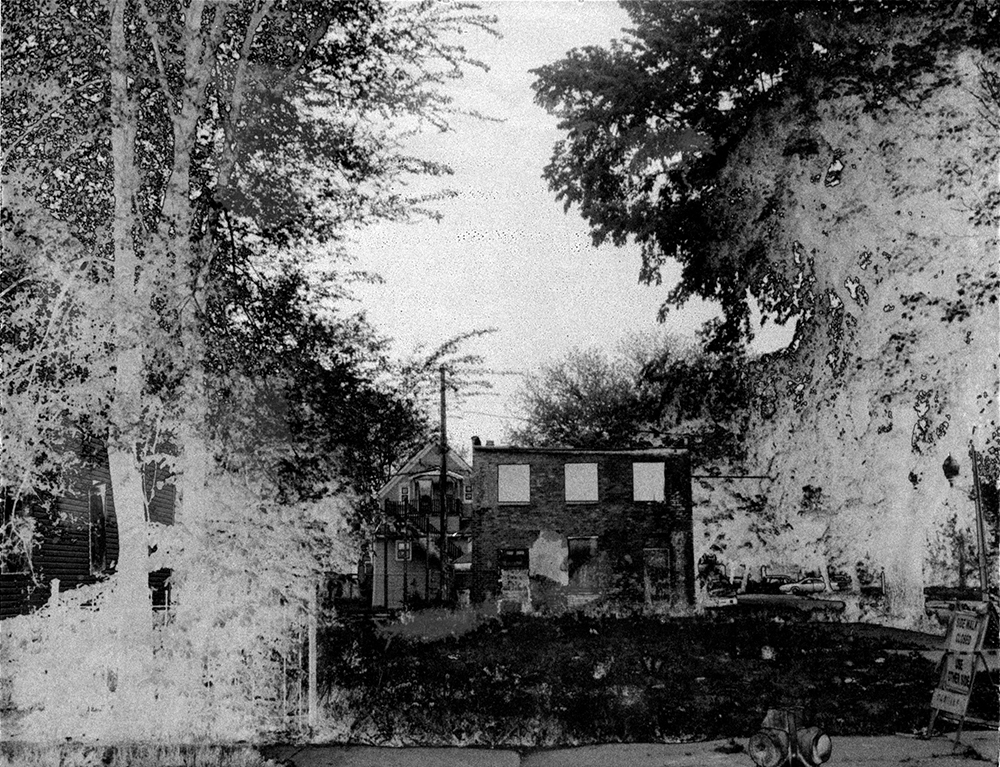

©Carlos Ortiz, Abandoned and boarded-up houses in Englewood. In time, nature tends to reclaim the landscape. Englewood, Chicago, 2013

We All We Got

We All We Got explores the consequences and devastation of youth violence in contemporary America from 2006 to 2013, through a mix of powerful photographs, incisive essays and moving letters from diverse individuals affected by this perennial scourge.

My work provides an avenue for knowing these children and their families. This work is not the end of the conversation about youth violence and society’s complicity in it, but rather the beginning. The terror in the eyes of grieving children and inconsolable mothers only allows the viewer to begin to understand the toll that this reality takes on the children who live it.

The stories take place in Chicago and Philadelphia. By repeatedly returning to the same neighborhoods over the course of eight years, I show the plight of the communities with which he has built a deep connection. You see abandoned buildings, memorials for victims, segregation, graffiti, juvenile incarceration and other constant reminders of the outcomes of violence on young people and their surroundings.

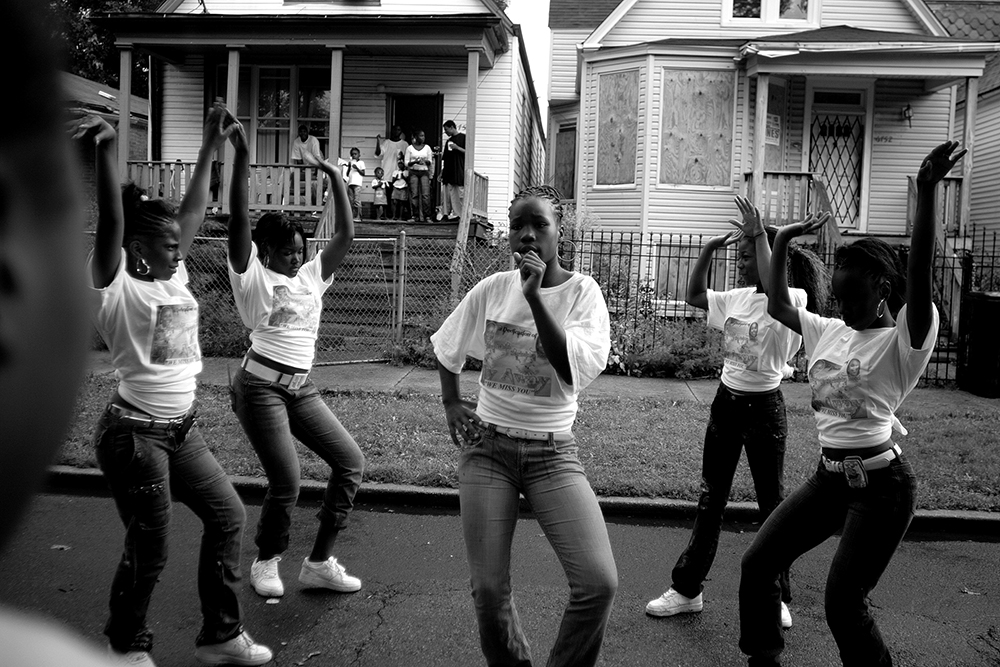

But through all the heartbreak, you also see the incredible resilience of the individuals left behind. And where there is terror, there is also a glimpse of the innocence that remains and a tiny glimmer of hope.

©Carlos Ortiz, Chastity Turner, 9, was washing her dog near her grandmother’s house on the 7400 block of South Stewart Avenue when a van pulled up and three young men fired opened fire. One of the bullets hit Chastity in the back as she ran toward the house. Her father, Andre Turner, 30, may have been a target of the attack. Greater Grand Crossing, Chicago, 2009

©Carlos Ortiz, Girls in the Englewood neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side attend a block party to celebrate the lives of Starkeisha Reed, 14, and Siretha White, 12. Starkeisha and Siretha were killed days apart in March 2006. The girls’ mothers were friends, and both grew up on Honore Street, where the celebration took place. Englewood, Chicago, 2008

©Carlos Ortiz, Young boys continue to play in empty lots after the deaths of their neighbors, Starkeisha Reed, 14, and Siretha White, 10. Englewood, Chicago, 2006

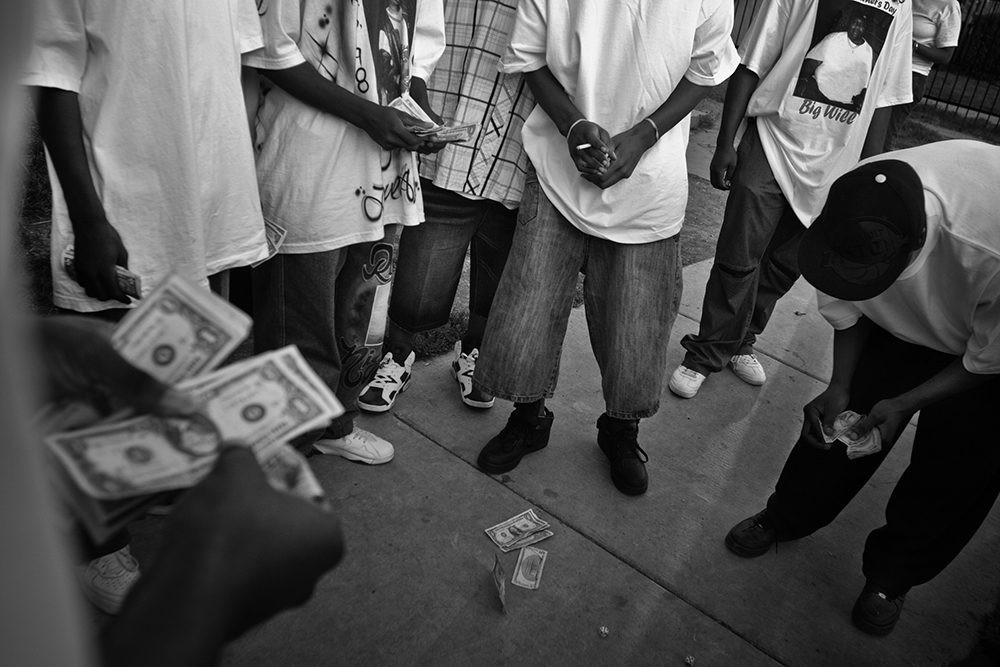

©Carlos Ortiz, Young men pass time by playing dice on South Marshfield Avenue and West 69th Street. Englewood, Chicago, 2006

©Carlos Ortiz, Siretha White’s family and friends lay flowers on her casket at her funeral. The shootings of 10-year-old Siretha, only eight days after the shooting of 14-year-old Starkeisha Reed, saddened and shocked the community. Both deaths were a result of gang violence with assault weapons. Englewood, Chicago, 2006

©Carlos Ortiz, The Rev. Jesse Jackson and Hadiya Pendleton’s parents gather at a press conference to address gun violence in Chicago. Hadiya, 15, was shot in the back while hanging out with friends at a North Kenwood neighborhood park. She was killed only one week after performing at events for President Barack Obama’s second inauguration. First Lady Michelle Obama attended the funeral in Chicago. Auburn Gresham, Chicago, 2013

©Carlos Ortiz, Albert Vaughn was the neighborhood guardian, the older teenager who would play ball with the younger kids and try to keep them safe from trouble. About 50 of his friends and family members gathered to remember “Lil Al” on the block where he was killed. Englewood, Chicago, 2008

©Carlos Ortiz, Angry community members, business owners and church pastors marched through Chicago’s South Side to protest the overwhelming number of murders that took place in October of that year. Greater Grand Crossing, Chicago, 2009

©Carlos Ortiz, Alex Arellano, 15, was shot and burned after being hit with bats and then struck by a car that was chasing him. Gage Park, Chicago, 2009

©Carlos Ortiz, Jalil Speaks’ aunt cleans her nephew’s blood off the sidewalk. The 16-year-old boy was killed in front of Strawberry Mansion High School. Jalil failed to pay $50 he lost in a rap contest, and many believe that was why he was killed. Jalil also had a handgun and exchanged fire with his killer. Strawberry Mansion, Philadelphia, 2004

©Carlos Ortiz, A friend of 16-year-old Jalil Speaks sits next to a sidewalk memorial. Jalil was shot and killed outside a Philadelphia high school shortly after classes let out at 3 p.m. Strawberry Mansion, Philadelphia, 2004

©Carlos Ortiz, The Bud Billiken parade, the oldest African-American parade in the country, kicks off the new school year and celebrates black life in Chicago. Washington Park, Chicago, 2013

©Carlos Ortiz, Murals inside the state juvenile detention center in Chicago. Near West Side, Chicago, 2010

©Carlos Ortiz, Darius Brown was playing basketball with his friends at Metcalfe Park when a white car drove by and sprayed the crowd of young people with bullets. The next day, the playground was stained with blood. Protests and a cry for peace followed. Bronzeville, Chicago, 2011

©Carlos Ortiz, Members of St. Sabina Church pray to end violence in Chicago. More than 50 young people have been murdered in the neighborhood since 2006. Auburn Gresham, Chicago, 2013

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026