Photographers on Photographers: Nick Drain in conversation with Alanna Fields

I cannot remember where I first encountered the work of Alanna Fields, but I can tell you what I do remember. It was in 2019, and like what has seemingly become the norm for all of my encounters with new work, it was probably on Instagram— likely a post showcasing Alanna’s thesis work upon the completion of her MFA, which she received from Pratt that year. The images contained right-angles and primary colors and Black people both presented to be looked at and to look back. I cannot remember the account that introduced me, and though I could probably find it if I really tried, I find it more poetic not to. What I remember is that I saw the work, and I immediately combed through Alanna’s website searching for more. I learned that the images I had just seen were a part of— what I now know to be— her As We Were Series. I know that I saw Alanna’s work and I haven’t forgotten it since.

I never followed up on my curiosities beyond an Instagram follow and an intrigued eye, so when I was approached to participate in this interview series, it occurred to me that there was no better opportunity to get answers to the questions that have lingered from that day, and those that I have had the opportunity to form in this process. I’m grateful to those at Lenscratch for allowing me the opportunity to partake in this interview series and scratch that itch (I’m sorry, I had to). For those reading that are not yet familiar, I hope that your first introduction with Alanna’s work will look something like mine.

Alanna Fields (b. 1990, Upper Marlboro, MD) is a lens-based mixed media artist and archivist whose work examines the dialogue between black queer bodies in the photographic space through gesture, aesthetics, and the negotiation between legibility and masking. Fields’ work has been featured in exhibitions at Pt. 2 Gallery, Residency Art Gallery, Felix Art Fair in LA, UNTITLED Art Fair in Miami, MoCADA, Pratt Institute, and the Prince George’s African American Museum and Cultural Center. Fields is a 2018 Gordon Parks Foundation Scholar, 2020 Light Work AIR, 2020 Baxter St CCNY Workspace AIR, and the recipient of Gallery Aferro’s John and Lynn Kearney Fellowship. Fields received her MFA in Photography from Pratt Institute in 2019, and currently lives and works in New York City.

Nick Drain is a fine artist born in Chicago, IL, who lives and works in Milwaukee, WI. Centering his thinking around blackness, his work questions the politics of visibility in an effort to understand the complex relationship of blackness and Black people to the object of the camera. He has exhibited locally and nationally, most notably showing work at the International Center for Photography in New York City, NY, and the Colorado Photographic Art Center in Denver, CO. Nick attended the Yale Norfolk School of Art in 2019 and received a BFA from the New Studio Practice program at the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design in 2020.

Nick Drain: Hi Alanna! I’m excited to be speaking with you in this format. Before we start, would you tell me a little about yourself? What should people know about you?

Alanna Fields: Hi Nick. It’s great to connect with you as well. I am a lens-based mixed media artist. My work investigates and challenges representations of black queerness through my engagement with Black American vernacular photography.

ND: I first encountered your work back in 2019, and ever since then I’ve been appreciative of it. I think that I was first introduced to your work through your As We Were series, and I was immediately drawn to your treatment of images in the work, and intrigued by the formal similarities to the De Stijl movement. Can you talk about this body of work, and where it fits into your practice as a whole?

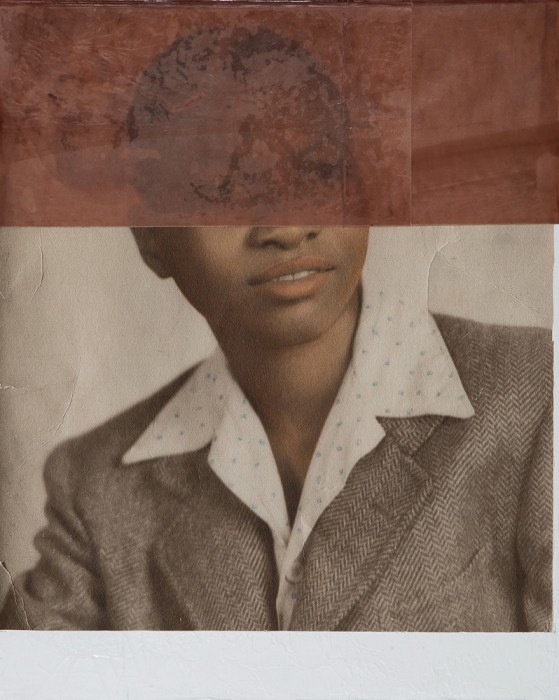

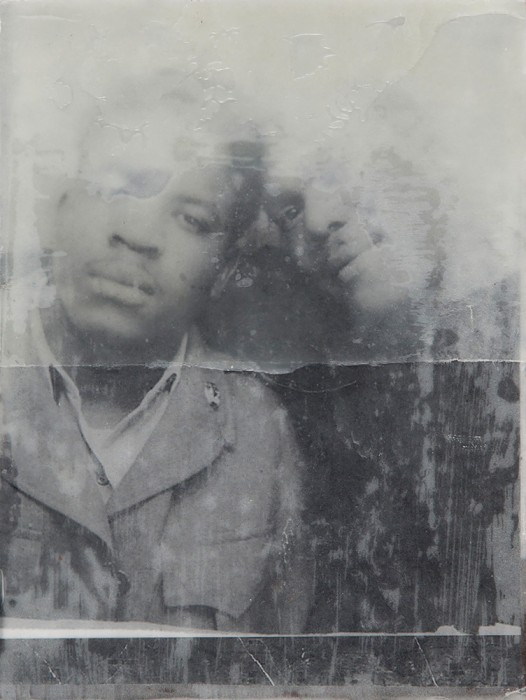

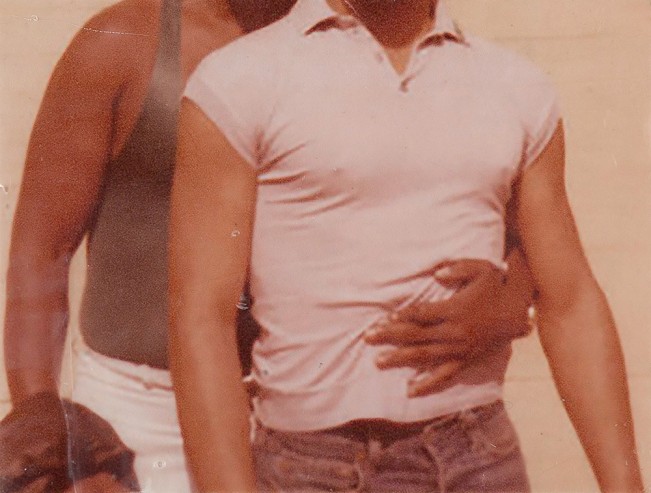

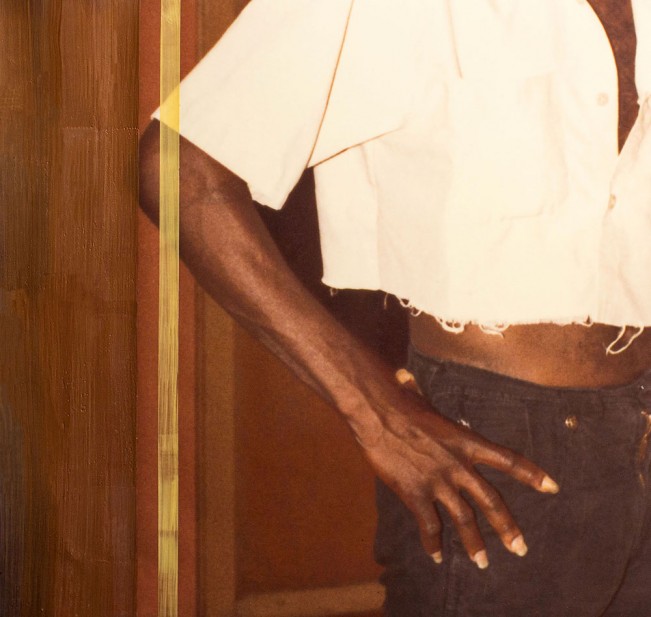

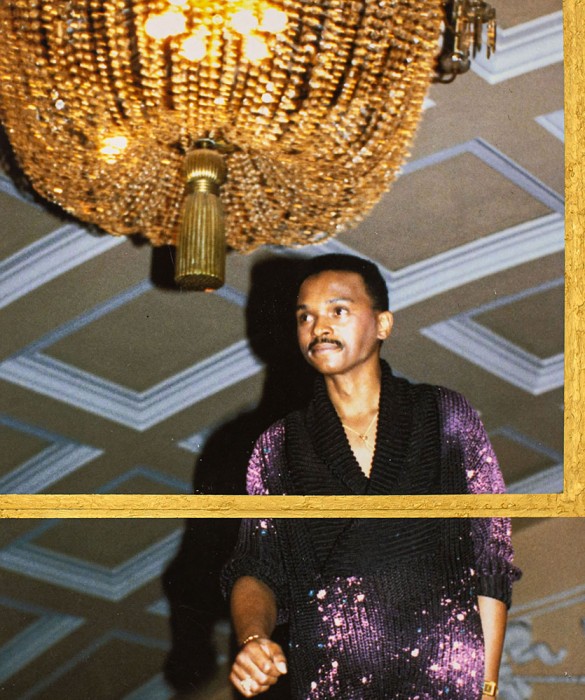

AF: As We Were, as a body of work is an introspective gesture where the finding of oneself is achieved through the finding of one’s ancestors. This series was a quest to uncover representations of black queer life in early photography as a means to decontextualize how black queer life has been recorded culturally and historically.

One of the brilliant ideas behind the De Stijl movement I think is that through our relationship to color we find order. Within my practice, I utilize color as a means of rebellion, disruption, and counter-narrative. In Dreadful Funkiness, the pairing of red, white, and blue counters the white patriarchal narrative of the “American Dream” complicated by blackness and queerness.

ND: I certainly can appreciate the application of color as a means to subvert and disrupt. While on the subject of the formal elements in your work, I’m curious about your employment of wax as the means through which these images are often obscured. Does wax serve a similar purpose or hold a similar significance in the work?

AF: Conceptually, the function and symbolism of wax in the work serves a means to seal and memorialize black queer history and to visually address how black queer life and representation has been historically obscured and invisibilized.

ND: Your work speaks on visibility and representation through masking and obfuscation, which I find to be an intriguing paradox; covering in the pursuit of uncovering a history and lineage.

Oftentimes in marginalized communities, there are things kept secret from those who are not members of the community in order to ensure the safety of the group and its members. More than likely, this would have been the case for those in the images you repurpose, as Black, queer people. In my own work, I have been thinking about the flipside of representation— the strengths that can come with invisibility— and I am a little curious to know if you have any thoughts on that, or more generally, what your thoughts are on the value of representation. Why do you feel that representation is important, and how does the masking in your work function in relation to that?

AF: I think about this often. For marginalized communities, photographs have always functioned as a proof of existence and doubly as a way we want to remember ourselves. As Black, queer people, our representation and recording of our histories are complicated by our intersections, and thus we have historically had to soften our queerness for survival’s sake. This shows up especially in early vernacular photographs where there is a common theme of hiding in plain sight. It is important to honor those experiences in my work, the suppression, the masking, and ultimately the breaking through the veil.

ND: Honoring not only the moments of triumph or the moments of struggle, but making space for both simultaneously is something that I appreciate, and something that I would really like to see more of in art generally. In one of the documents you sent me ahead of us speaking here on record, you mentioned the term ‘black queer audacity’. I’d never encountered the term before, but upon reading it I instantly knew that it was something that I wanted to know more about. Can you speak on that term and what it means for you?

AF: ‘Black queer audacity’ as I’ve referred to it, is the radical nerve to reject the silencing and the softening of one’s queerness for palpability. In my work, you see the progression of this audacity through fluid presentations of gender and embodiments of both masculinity and femininity through aesthetic, posture, and gesture.

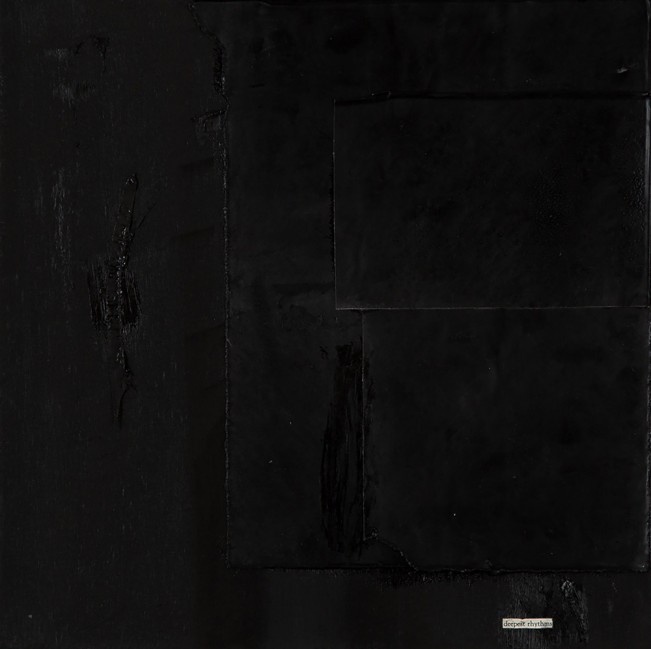

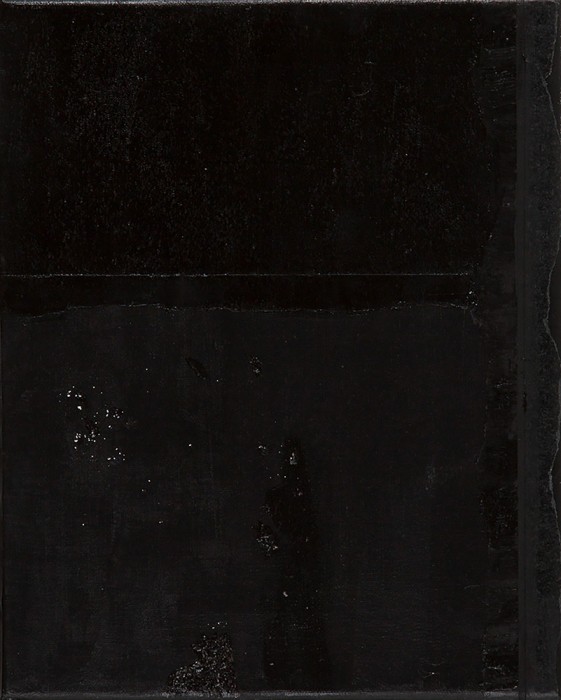

ND: Explained in that way and with some of the other things you’ve said here, the methods and aims of your Audacity series become much more apparent. Though it was your As We Were body of work that brought me the desire to speak with you, I’d like to address one more body of work before we close out. Of all of your work, Black Series is notably different in that it does not directly feature any photographic figural representation. How do you contextualize this body of work alongside the rest of your oeuvre? What function do you feel that it serves in relation to the rest of your work and practice?

AF: The ‘Black Series’ exists as a visual ode to Black American life and culture through an abstract engagement with layers, sculpture and variations of blackness. Each piece in the series visually highlights themes of intersection and oral history through line work, texture, and material. All of my work and practice is an exploration of black life and existence and how we have shown up in history over time, ‘The Black Series’ I hope, captures the synergy of our shared experiences as well as our nuanced ones.

ND: What’s next for you? Is there anything on the horizon that you’d like to plug?

AF: I have a few things in the works right now but I am really excited to share some new work in Light Work’s Annual 2020 Contact Sheet and I’ll be showing work alongside some great artists in a group exhibition at the University of Minnesota in the fall.

ND: For my final question, I’m going to take some inspiration from a question posed to me in a recent interview that I really liked and have come to appreciate quite a lot. We are unquestionably living through history in the making. Whether it be a piece of advice, a rallying call, sage wisdom, or even a moment of exhalation— with the state of our world as it is, what’s one thing that you think people need to hear right now?

AF: I’ll speak on what I feel my community needs to hear right now. It is these words I refer to when I need affirmation of my powerful resilience and that of my ancestors. June Jordan said “We are the ones we’ve been waiting for,” and this must be our rallying call, ancestral wisdom and self-exhalation, now more than ever.

ND: Having this conversation has felt like getting to close out a browser tab that I’ve had open for a very long time now haha, so thank you for taking the time out to speak with me. Stay safe.

AF: Thank you. Sharing with you has been my pleasure.

Keep up with Nick here:

www.nickdrain.com / @nckdrn

Keep up with Alanna here:

www.alannafields.com / @alannafields

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Hugh Kretschmer: Plastic “Waves”April 24th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Richard Lloyd Lewis: Abiogenesis, My Home, Our HomeApril 23rd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024