American Masterpieces at the Los Angeles County Art Museum

The Los Angeles County Art Museum is feeling Au courant again, some of it due to the new addition of the Broad Center, some to the new curator of photography, Britt Salveson, and now, some to a terrific small exhibition that is a response and a counterpart to the exhibition, American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765-1915. The photographic echo is titled, In Color: New American Stories from LACMA’s Photography Collection. The show is comprised of a handful of large-scale color photographs by contemporary artists who worked or are working in the United States. Though the paintings and the photographs viewed below do not hang side by side (each are taken from both concurrent exhibitions), they resonate in their pairings (created and written for the LACMA blog by Sarah Bay Williams). The exhibitions run through May 23rd, 2010.

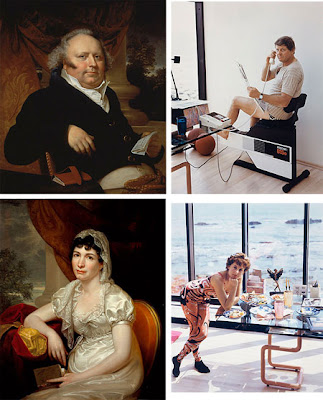

Rembrandt Peale & Joel Sternfeld

On the left, above, we see portraits of Mr. Jacob Gerard Koch, a wealthy Philadelphia merchant, and Mrs. Jane Griffith Koch, his wife, by Rembrandt Peale. On the right are Joel Sternfeld’s portraits of (what can be assumed to be) a couple in Malibu, an investment banker and his Pucci spandex-clad ladyfriend. The similarities? Both Peale and Sternfeld use architectural details such as columns and drapes (Koch) and drinking cups and floor-to-ceiling windows (Malibu) to indicate that the portraits are possibly to be viewed in tandem. In both sets, the male figure is seen to be in the midst of reading or reviewing correspondence—Koch with a letter in hand and the investment banker deftly multitasking between phone, newspaper, and exercise bicycle (the last of which history tells the stout Mr. Koch was sorely in need). The females appear more at ease, dressed attractively, and in the midst of reading (Mrs. Koch) and having a healthy lunch (Malibu). Even the males both have a tiny bit of flair to their dress—Mr. Koch, with a kerchief of red with flecked gold, and the investment banker with just a peek of, well… leopard print tighty whities, of course.

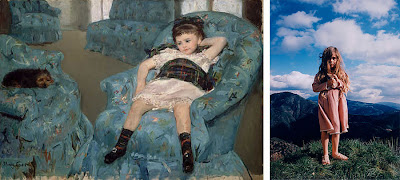

Mary Cassatt & Sharon Lockhart

The random scattering of blue club chairs and a deep blue sky thick with clouds echo each other here—but the psychology of Mary Cassatt’s Little Girl and Sharon Lockhart’s Ruby suggest comparable tone as well. Both images portray girls of a similar age, disheveled and accompanied by an animal—Lockhart’s Ruby holds a rat, while Cassatt’s Little Girl is sacked out by a proper dog (Cassatt’s own Brussels griffon). Lockhart’s Ruby, looming large in front of the viewer, seems to both own the world and to be in danger of falling into it—at cliff’s edge. Cassatt’s Little Girl reclines in posture like a bathing beauty, but is intentionally painted as just a little girl worn out from play. The brash informality of these images foreshadows the autonomy of adulthood while granting the viewer those true moments of childhood.

John Singleton Copley & Tina Barney

John Singleton Copley’s Portrait of a Lady and Tina Barney’s Jill and the T.V. portray subjects with items and dress that depict wealth, such as the upholstered sofa and silk reclining gown of Copley’s Portrait and the large television and silk kimono of Barney’s Jill. But look at those eyes! In Copley’s portrait, the simple realism of a vacant background, not a jewel on her person to be found, and little sartorial decoration is heightened by a quiet confidence in her stare, with a slight angle to the face as if in serious consideration of the viewer. Barney’s Jill, also intense, is mid-sentence, looking beyond the camera plane and seemingly interrupting whatever was on that television, relegating it to permanent background noise and almost geometric abstraction.

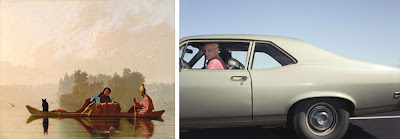

George Caleb Bingham & Andrew Bush

In reference alone, these images could be thought of as similar—two vehicles of river and road traveling alongside our viewing plane. However, George Caleb Bingham’s Fur Traders Descending the Missouri speaks much more of the waterway of the Missouri and the opportunities this brought to those who were seeking resettlement and trade. As described in the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, the image can be “read from left to right—against the flow—from the native bear cub chained to the boat’s prow, to the boy reclining on the pelts, to the man at the stern, a straight line from the beast to civilized humanity.” Andrew Bush’s Man Driving Southwest, part of his series of Vector Portraits of people driving 50 to 70 miles per hour in Los Angeles and the surrounding environs, studies the car/human relationship as an extension of personal space. In a city of highways, such as Los Angeles, the car becomes another form of dress and a comfort zone, or, in the case of what Bush guesses to be an air conditioner malfunction, perhaps the decline of civilized humanity.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and Photography, Part 2January 22nd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and PhotographyJanuary 21st, 2026