Kirsten Hoving: Working Stone

The name Kirsten Hoving may be more familiar as the Director of the PhotoPlace Gallery in Vermont , a gallery that continually champions emerging photographers, or as a Professor of Art History at Middlebury College, or the mother of the photographer, Emma Powell, but she too is also a talented photographer. We are grateful that she sets her camera aside to create monthly opportunites for photographers, mounting in-gallery and on-line line exhibitions (complete with a catalog), but when she does get time to create photographs, they are varied and quite special. I featured her work from Night Wanderers on Lenscratch last year.

The name Kirsten Hoving may be more familiar as the Director of the PhotoPlace Gallery in Vermont , a gallery that continually champions emerging photographers, or as a Professor of Art History at Middlebury College, or the mother of the photographer, Emma Powell, but she too is also a talented photographer. We are grateful that she sets her camera aside to create monthly opportunites for photographers, mounting in-gallery and on-line line exhibitions (complete with a catalog), but when she does get time to create photographs, they are varied and quite special. I featured her work from Night Wanderers on Lenscratch last year.

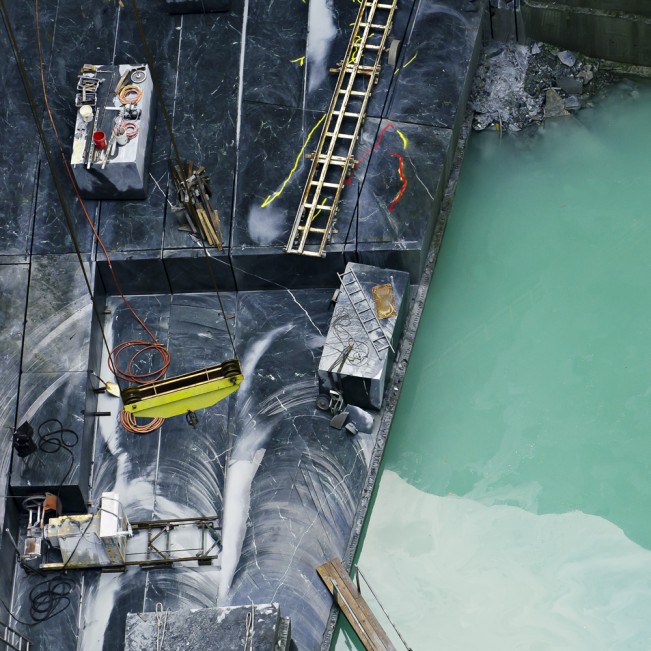

Today I am featuring a new body of work created in a state that is typically known for the fireworks of fall foliage, but it also is rich with rock. Working Stone, explores Vermont rock quarries , “workplaces whose scale dwarfs the men and machines“.

Kirsten is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Art History at Middlebury College, where she has taught courses in Modern Art and the History of Photography for over 30 years. She is also the co-director of PhotoPlace Gallery in Middlebury. Working Stone is a project that grew out of her fascination for the rocks under her feet and her delight at being a 60-something woman tromping around with the guys in her very own hard hat.

WORKING STONE

Nearly half a billion years ago, my home state of Vermont lay under a warm, shallow sea. Prehistoric marine organisms, whose fossils are still visible on rocky outcrops, built reefs that, over the eons, turned to limestone. Continents collided, mountains taller than the Himalayas rose, and under great pressure sediments of marine limestone on the western side of the state metamorphosed into marble. The igneous granite deposits to the east formed from the slow crystallization of molten rock below the surface of the earth. Rocks made from ancient undersea creatures and rocks of pressurized lava – these are the hallmarks of the geological and historical landscape that lies under my feet.

In more recent history these rocks have been quarried, first by Abenaki and other native tribes for tools, then by farmers who walled their land and built sturdy houses, and now by industrialists who extract huge blocks of marble and granite before abandoning one site and moving on to the next. There are still active open pit and underground quarries in Vermont, although there are many more abandoned ones slowly succumbing to water and weather and time.

In more recent history these rocks have been quarried, first by Abenaki and other native tribes for tools, then by farmers who walled their land and built sturdy houses, and now by industrialists who extract huge blocks of marble and granite before abandoning one site and moving on to the next. There are still active open pit and underground quarries in Vermont, although there are many more abandoned ones slowly succumbing to water and weather and time.

Many photographs in Working Stone explore the active quarries of Vermont, workplaces whose scale dwarfs the men and machines that remove massive blocks of rock to be shaped into tombstones or ground into mountains of small pebbles for making roads or even toothpaste. Other photographs contemplate inactive sites, whose rock faces still bear traces of human interaction with the geologic landscape. I am fascinated by the way the stone has been and is still worked–by the ladders, hoses, bolts, and derricks, by the trucks and saws and generators. But most of all, I am drawn to the stone itself, with its textures, colors, lines, and marks reading like a map of time stretching back beyond human imagining.

Many photographs in Working Stone explore the active quarries of Vermont, workplaces whose scale dwarfs the men and machines that remove massive blocks of rock to be shaped into tombstones or ground into mountains of small pebbles for making roads or even toothpaste. Other photographs contemplate inactive sites, whose rock faces still bear traces of human interaction with the geologic landscape. I am fascinated by the way the stone has been and is still worked–by the ladders, hoses, bolts, and derricks, by the trucks and saws and generators. But most of all, I am drawn to the stone itself, with its textures, colors, lines, and marks reading like a map of time stretching back beyond human imagining.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026