Ashlyn Davis on Morgan Ashcom: What the Living Carry

I asked Ashlyn Davis, Executive Director of the Houston Center for Photography, to comment on their most recent exhibition by artist Morgan Ashcom, What the Living Carry. The show will be on display until November 11, 2018. Morgan’s monograph of the same name was published by MACK books last year.

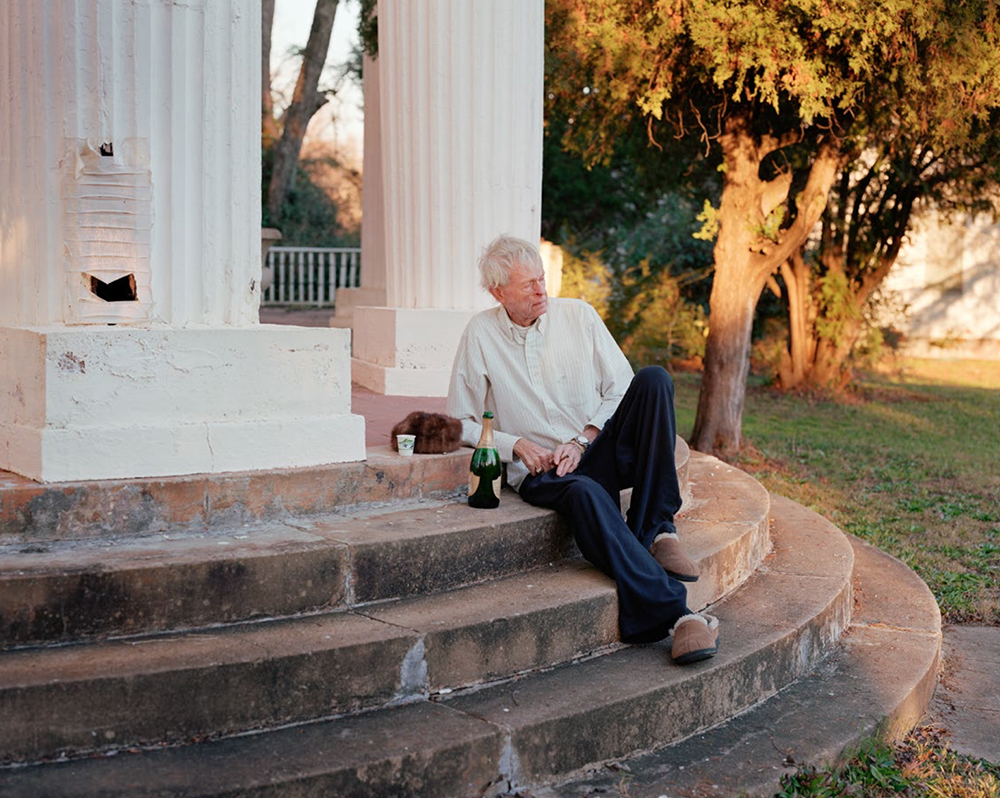

“In What the Living Carry, artist Morgan Ashcom presents the fictional town of Hoy’s Fork, a place inspired by memories of the rural American setting in which he grew up. Here, history, mythology, and visual culture intermingle to shape the fabric of place—from the architecture of its main streets to the genetic code of its inhabitants. Shot throughout various locales in the eastern United States, the project consciously picks up where many iconic photographs of the twentieth century left off.

Unlike Walker Evans or William Christenberry, however, Ashcom’s aim is not to show us what rural America looks like. Instead, these photographs present visual cues to stories, myths, histories, and ways of being that we carry on from the past.

What the Living Carry uses some of the classic tenets of the documentary aesthetic—large-format straight shots, ostensibly unedited views, and a mix of landscapes and portraits—to subvert viewers’ inherited beliefs about the veracity of photography, and particularly our easy acceptance that the realism of the photograph is real. In these photographs, we see real people and real places, yet together they present a view of a singular place that does not exist. It is simultaneously everywhere and nowhere, much like the past. Ashcom aims to challenge our assumptions of place by showing us—quite literally—that these inherited beliefs, practices, and vestiges of visual culture are more ubiquitous than we might think. ” –Ashlyn Davis, Executive Director

Could you introduce yourself to the readers, and tell them what you do for The Houston Center for Photography?

I am Houston Center for Photography’s Executive Director. On a daily basis I could be doing one of many different tasks, one of which is conceptualizing and organizing exhibitions in our gallery.

How did you first become acquainted with Morgan and his work, and how did this show come to be? Was there anything about the present moment, whether in the art world, politics, or the realm of social consciousness that made this work feel particularly important to showcase at this time?

I’ve known Morgan and followed the development of his work for the past several years. We originally met through other photographers in New York when he was completing his MFA in Photography at the Hartford Art School. When his second body of work, What the Living Carry, was published by MACK in 2017, I was excited to see a project that presented a complex, lyrical narrative while simultaneously engaging in a highly conceptual conversation about photography and culture.

Whether it’s a social, theoretical, or aesthetic issue, making the concerns that are actively shaping the world we live in accessible to a broad public through photography is one of the most gratifying outcomes of our exhibitions program. Morgan presents several overlapping themes in What the Living Carry that seem particularly resonant to our current moment, including the legacies of viewing rural America, the truth status of the photograph, and the present-day implications of popular versions of history. Ultimately, the project insists that we can’t assume anything based only on what we see. Given the conversations around fake news, post-truth, and our image-saturated environment, Morgan’s work seems like a prescient and accessible call to visual literacy through the photograph.

Morgan’s exhibition does not just contain his photographs, but also many other media and artifacts to expand upon what’s on the wall. Can you talk about some of these objects, and how they fit into the scope of Morgan’s work? As the curator, what was your experience in creating conversation between various mediums to form a complete portrait of this fictional town and its inhabitants?

This was one of the most exciting aspects of the exhibition for me, because these “untraditional” components of Morgan’s photographic project are built around his interrogation of truth in reproduction, but in a way that viewers might be more willing to accept. In a general sense, viewers have accepted the subjectivity of nearly all other forms of art and representation, but when it comes to the photograph, it’s still difficult. So, the objects more easily bring the viewer along that more theoretical line of inquiry.

In terms of our understanding of the town and people of Hoys Fork in a literary sense, these objects lend a physicality to Morgan’s construction of place and allow us as spectators to interact with this fictional world. With the gravestone, for instance, visitors are asked to place a sheet of paper on top of the object and make a rubbing, which is traditionally a way to transfer information from one surface to another. Yet, as the visitor runs the pastel over the paper they will see that the information will never fully appear. Or, we encounter the desk of a man we learn is Eugene, who from the letters and their carbon copies, we discover runs a “Center for Epigenetics and Wellness of the Spirit.” Eugene asks the visitors to leave a lock of hair for a DNA analysis—and many visitors do! This absurdist reference to epigenetics points to the more serious research being done in this area of science that studies, among many different environmental factors, how we essentially inherit the experiences of our parents on a cellular level. And finally, the vines formally echo the DNA helix referenced at Eugene’s desk, but they also stand in for the forest, which in a literary sense has a rich history as a symbol of the unknown and of the unconscious. Literally, though, these objects are thermoplastic prints—three-dimensional extensions of two-dimensional photographs.

All the objects ask us to think conceptually about inheritance through reproduction, the veracity of that reproduction, and ultimately, our past, present, and future definitions of the camera and lens-based representation. These are the threads that braid together to echo the narrative content of What the Living Carry—that while the past is never passed (to reference Faulkner), it also is never fully present, whether that’s photographically, through recorded history, or through genomic expression. When there is reproduction of any kind, there is an inherent loss of truth. It’s one of the biggest conceptual leaps the project makes, but also one of the most thrilling.

Something that strikes me most about Morgan’s photography is the employment of a very disciplined documentary style and color palette as a foundation to construct an atmosphere about Hoy’s Fork. What is your impression of Hoy’s Fork, what are you drawn to and how do you relate to it personally?

One of the underlying narratives of What the Living Carry is that the photograph—despite its ability to reproduce likeness to a near scientific degree—is unable to fully represent the truth. Photographically, Morgan uses a documentary aesthetic to point to his belief that there is really no objective document. The “documentary” portrayal of this fictional town allows the viewer to confront this idea in a way that feels comfortable, in a way that we are used to looking at photographs as images of real people and places.

I initially read Hoy’s Fork as a representation of the American South. The project asks us to do that and is full of references to a visual lexicon of visualizing the American South through photography. The brilliant maneuver Morgan makes is to show us something we think we know intimately, but that really, we know nothing about—because it’s fiction. It’s only until the viewer moves deeper into the project that they can begin to understand the fictional elements. The project pivots on our assumptions, and the exhibition actually depends on a second look—a reconsideration of what we think we see. That second look could happen inside the gallery, or after a viewer has left. It’s those lingering resonances that become one of the main aims in the presentation of the work at Houston Center for Photography. In a sense, the exhibition asks us to consider if it’s possible to redefine our relationship to the past and in doing so shape the future in a new image.

We have a tradition here at Lenscratch of asking the folks we interview to describe their perfect day. What’s yours?

The perfect day would involve some combination of time spent outdoors, ideally a hike or a swim in a secluded area, a really good novel or photobook, and a homemade dinner with friends.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026