James Friedman: States Project: Ohio

It is with great pleasure that we kick off the Ohio States Project week with two projects by the Ohio States Project Editor, James Friedman. James could be considered a national treasure of photography–he has been a photographic educator for 45 years, inspiring countless students with his enthusiasm and unique way of seeing the world. His own work reflects a wonderful curiosity, with projects ranging from Dogs Who’ve Licked Me to 12 Nazi Concentration Camps to Almost Never Before Seen Portraits of Remarkable People. His work reveals an artist who is all in, creating work with humor, poignancy, and inquisitiveness. He has created a remarkable legacy of interpreting the world.

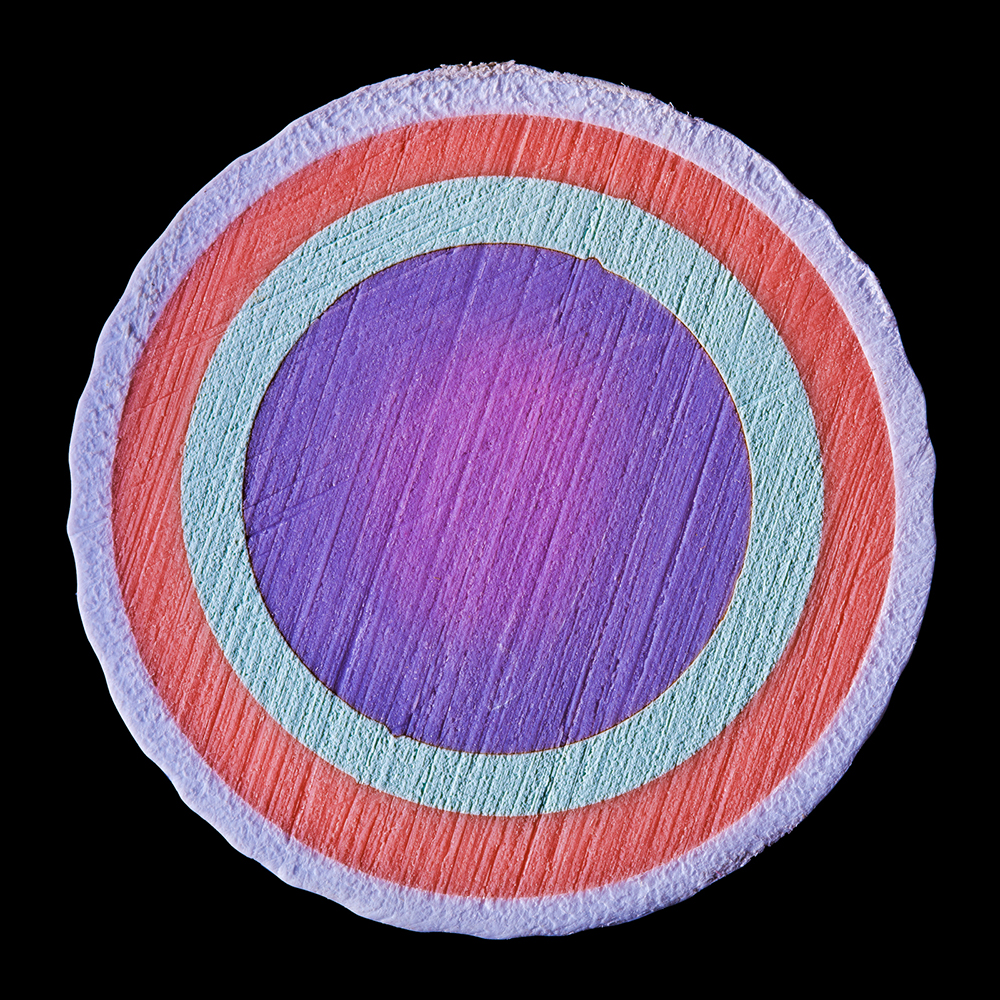

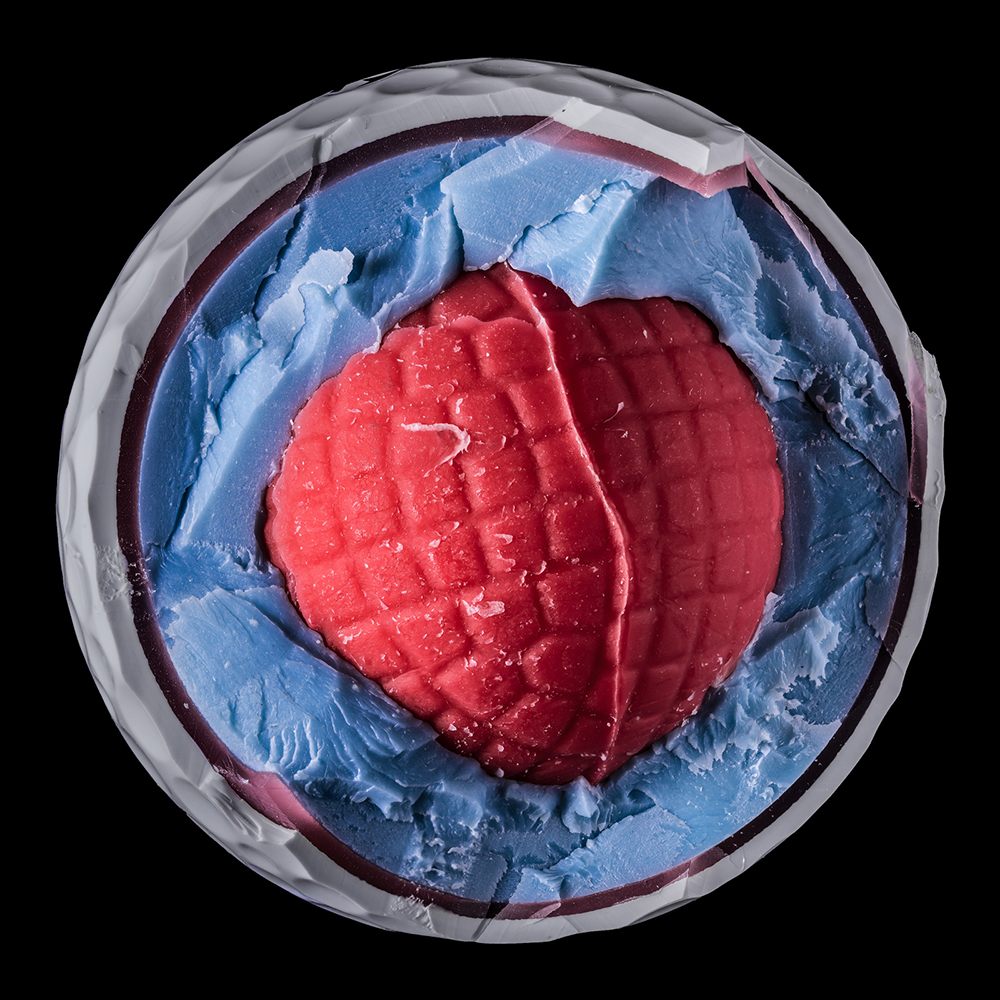

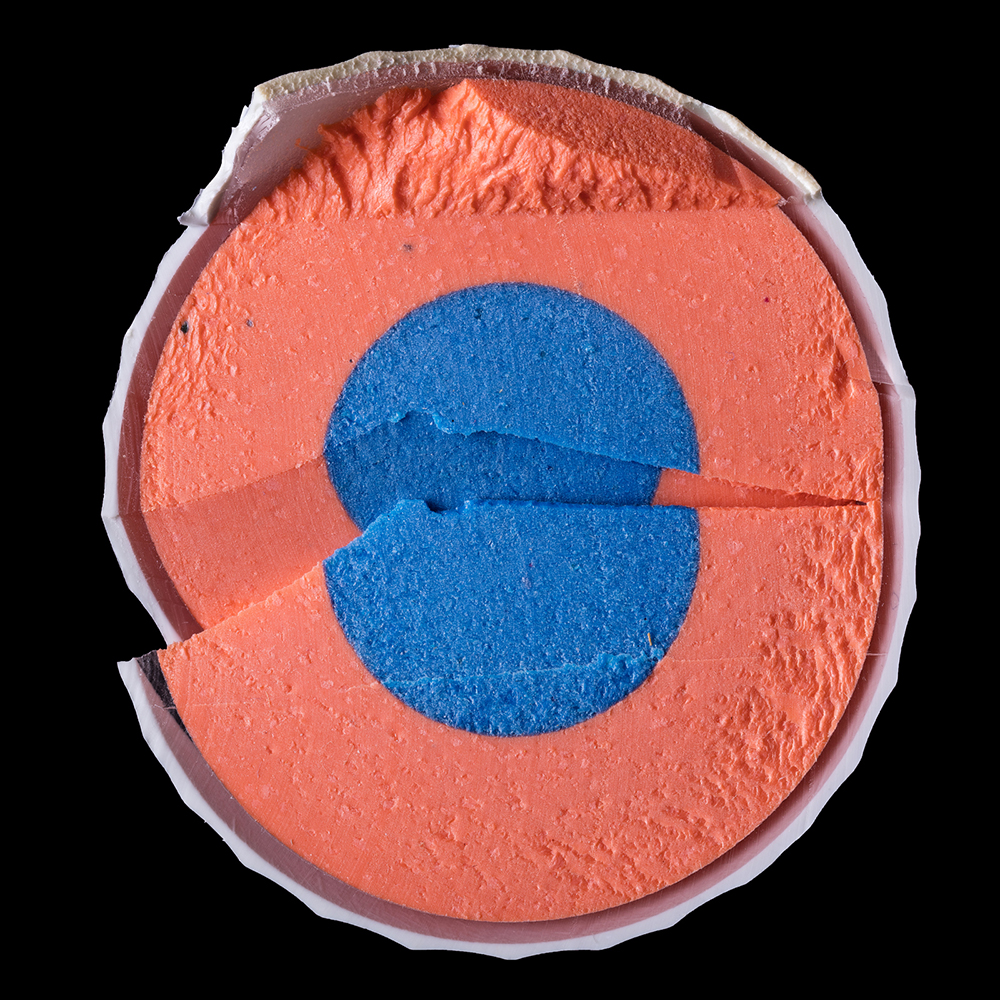

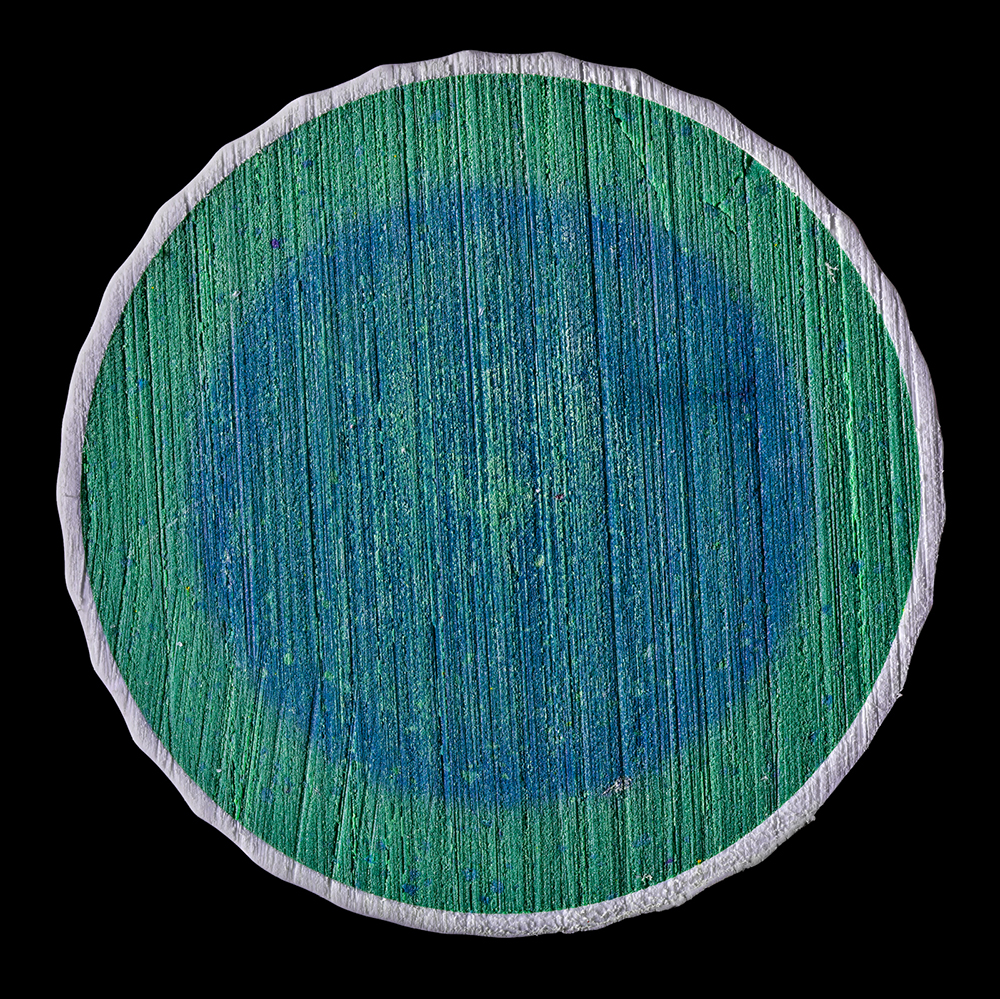

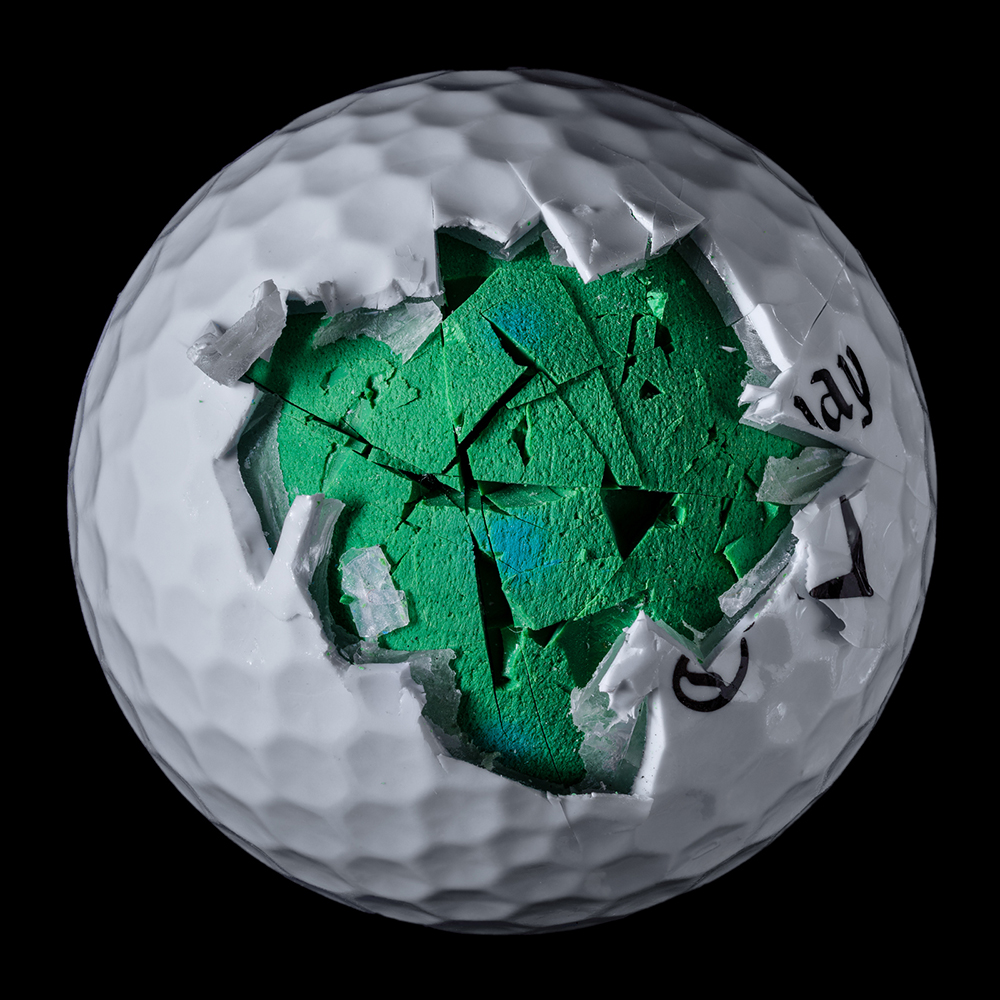

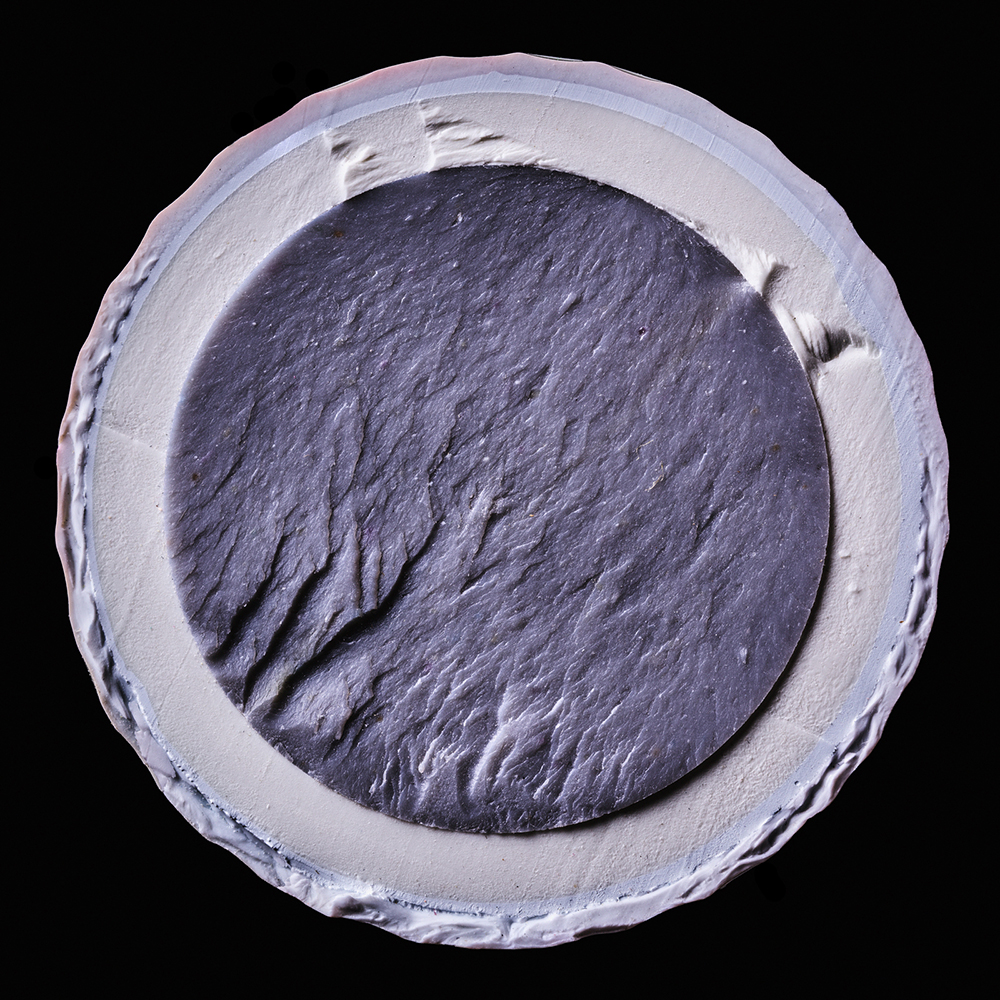

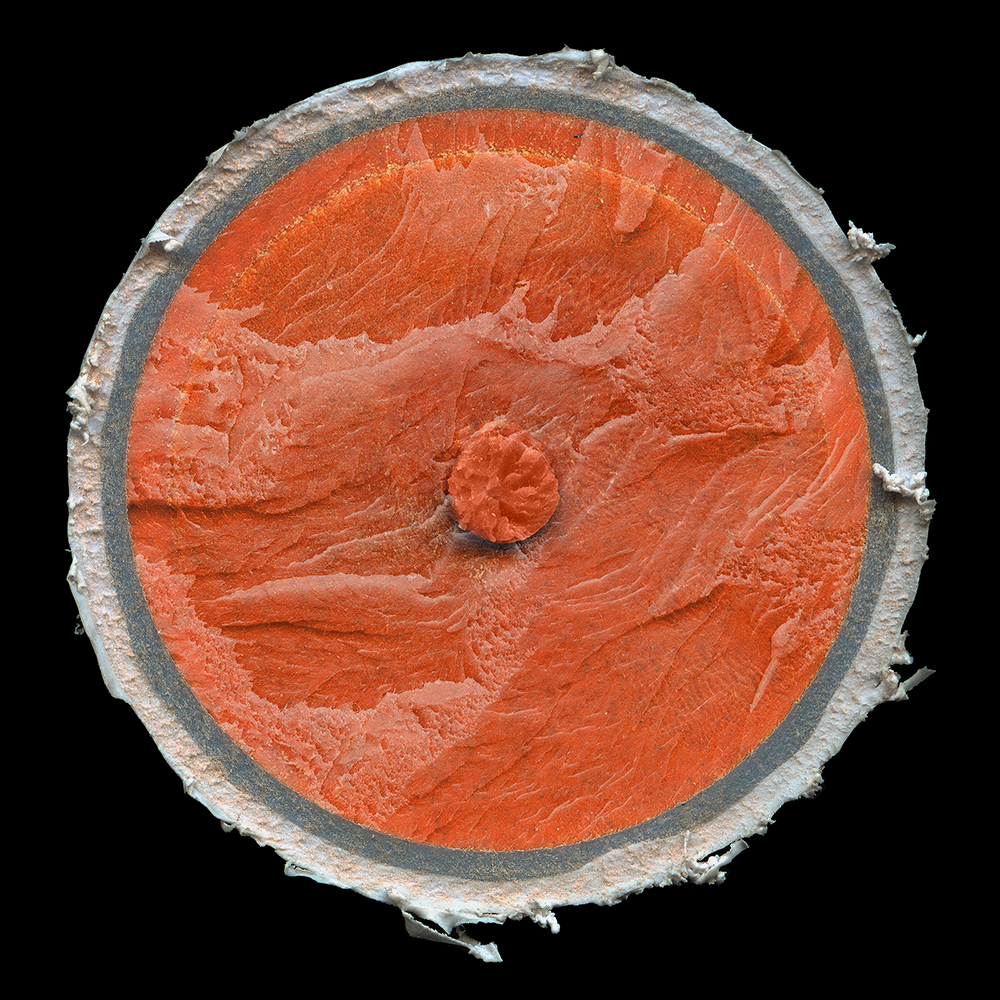

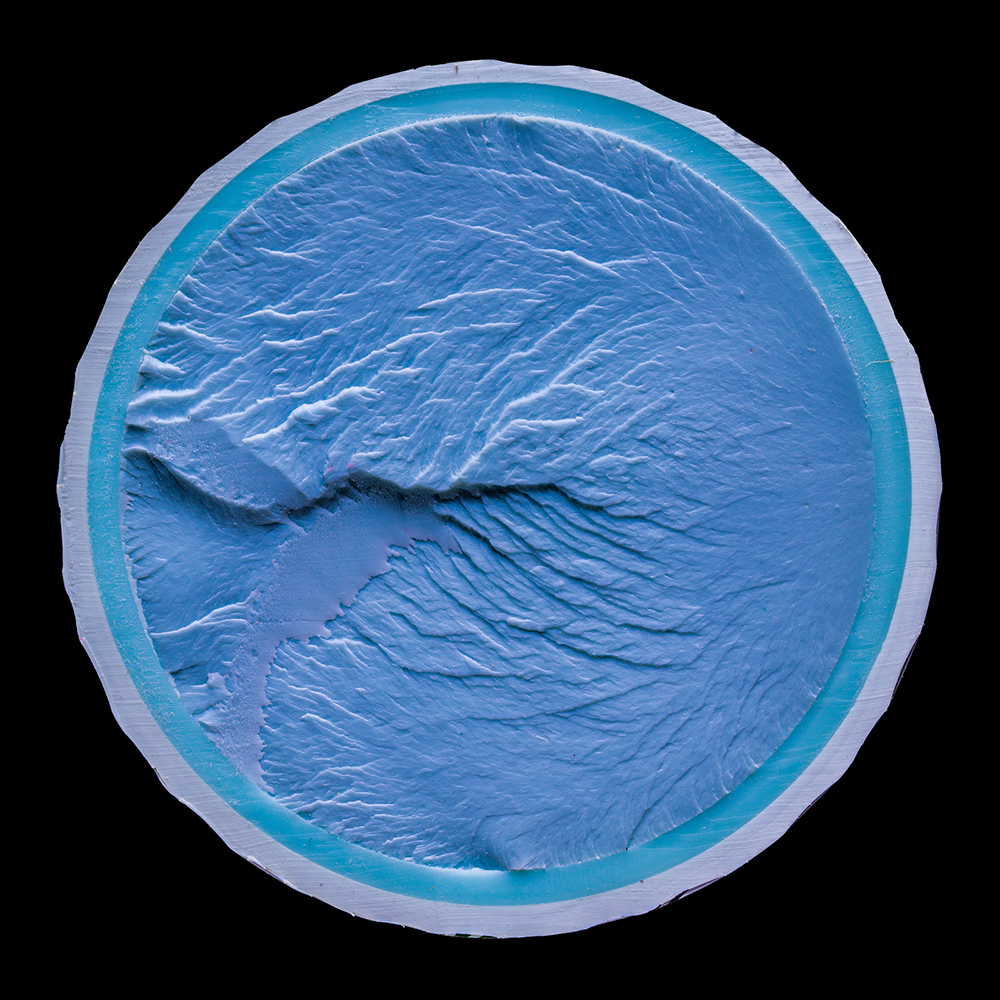

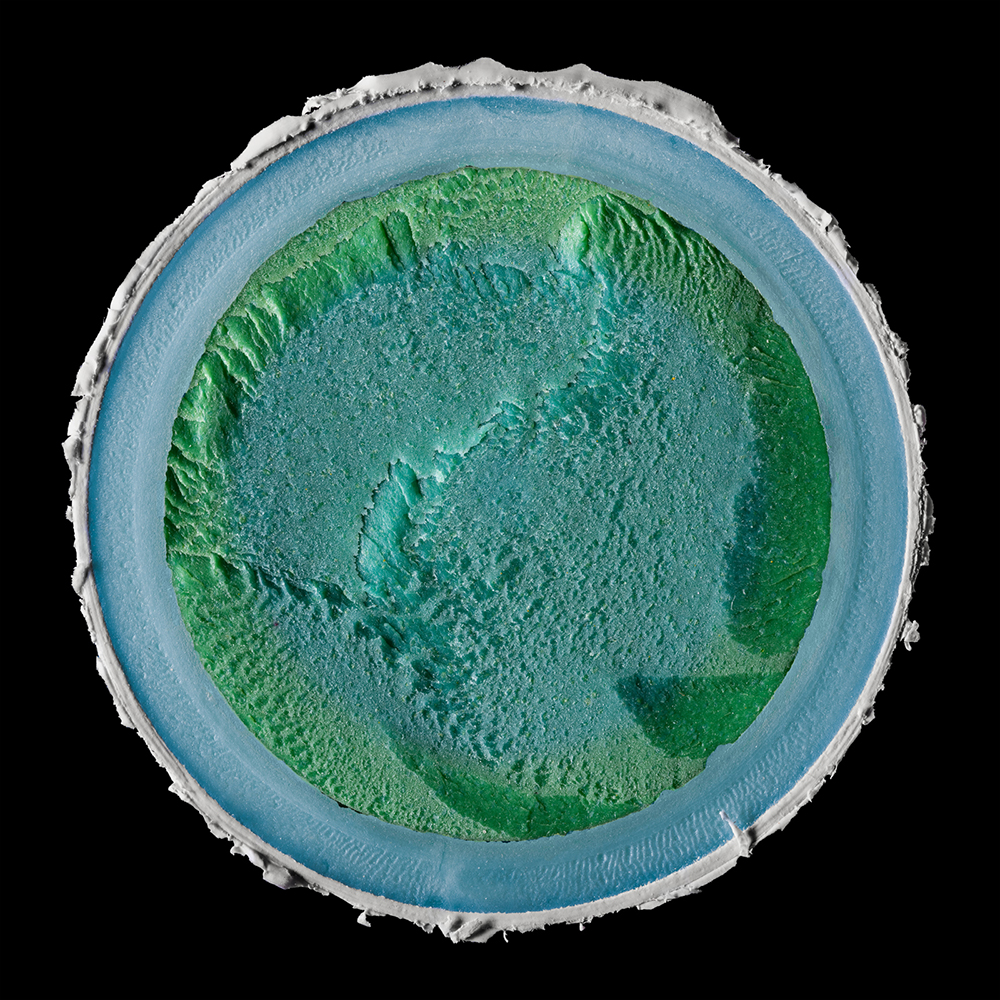

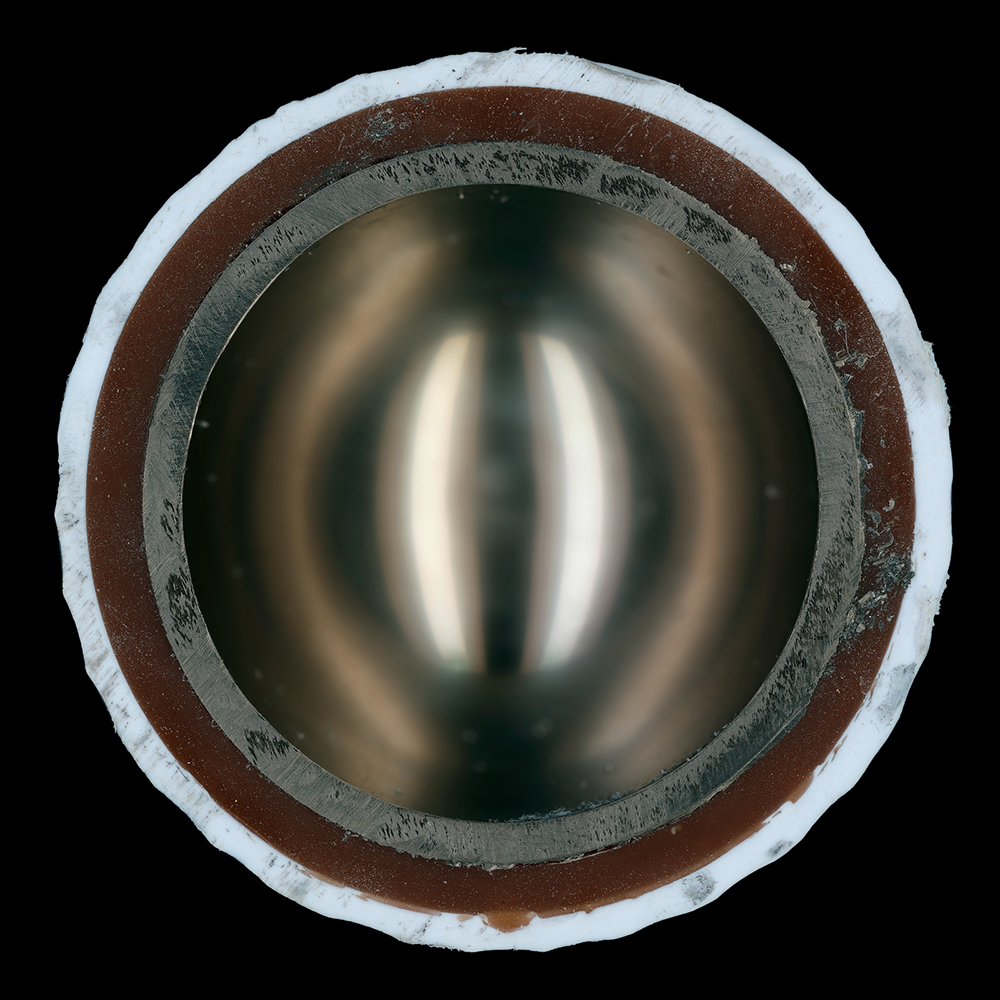

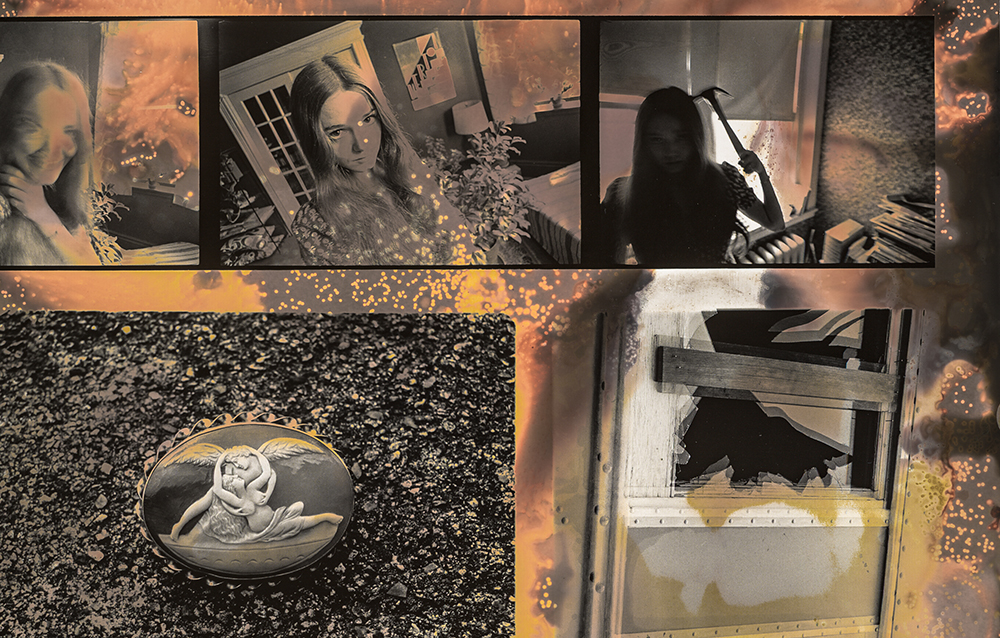

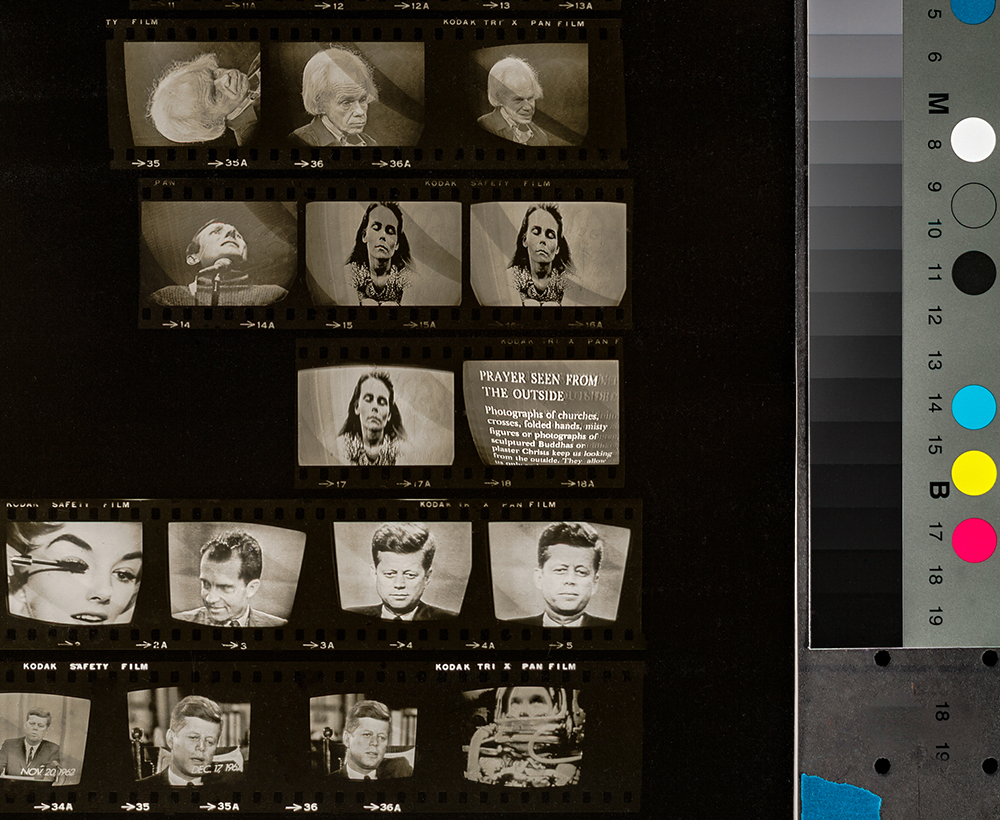

Today we feature Interior Design, a typology of golf ball interiors, and Unmasked, where he seeks to unmask the hidden potential for releasing color responses on conventional black and white photographic paper. An interview with James follows.

Interior Design

Although I studied with Minor White in an experimental graduate program in photography at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and admired his iconic photographic abstractions, for most of my career my chief interest has been in portraiture as a personal documentary and street photographer.

I never felt personally connected to abstraction until I happened to attend a golf equipment trade show and saw a bisected golf ball. For the first time, abstraction resonated with me as I discovered elegant formal qualities and surprising metaphorical possibilities in the unlikeliest of places, a 1.68” golf ball. Thirty-five years after first viewing the abstractions of photographers White and Aaron Siskind and the paintings of Helen Frankenthaler and Joan Mitchell, I learned to appreciate and embrace abstraction in my own work. For some viewers, my photographs from this series, titled Interior Design, allude to celestial bodies and the sublime. For me, their serendipitous structural exquisiteness and their subtle and passionate arrays of colors have inspired new exploration in my photography; I am particularly delighted to see the diminutive golf balls transformed into 36” x 36” prints.

Incidentally, I do not play golf.

James Friedman became a photographer when he made his first self-portrait the day after an anti-Semitic hate crime at his Midwestern suburban home. He was four years old.

Using a Kodak Brownie Hawkeye camera and film processed and printed at the corner drugstore – and, later in childhood, developing his own film in a bathroom at home – Friedman began a lifetime’s passionate commitment to the medium. He recalls that, as a child, “when I looked through the camera’s viewfinder, a world that could be confusing and sometimes fearsome seemed harmonious and balanced.”

Friedman was self-taught in photography until college. It was a desire to play on the varsity tennis team, not to study art, that led him to Ohio State, but he soon discovered the variety of photography courses the university offered and earned a BFA. He was one of five students accepted into an experimental graduate program in photography at MIT that would be the last graduate class directed by Minor White. He later did additional graduate work at San Francisco State University and during that time worked as an assistant to Imogen Cunningham. He is grateful to have had as mentors these two luminaries of 20th century photography, who taught him not only technique and vision but also how to devote his life to the medium.

Later in his career, the flashpoint incident of violence that prompted Friedman’s first, childhood self-portrait was among the events that inspired him to travel to Europe and photograph, in color, Nazi concentration camps. Friedman sees now what he didn’t understand as a child – that making that first, defiant self-portrait allowed him, even if indirectly, to confront and reckon with violence and trauma.

Friedman began a career teaching expressive photography in 1974 and has taught at Ohio State, Antioch College, Ohio Wesleyan University and Santa Fe Community College and as an independent educator. He also has enjoyed a long, successful career as a fine art photographer. Friedman was awarded the Aaron Siskind Foundation’s prestigious Individual Photographer’s Fellowship, has exhibited his photographs in more than 50 countries, was the recipient of the Governor’s Award for the Arts in Ohio (honoring an individual artist whose work has made a significant impact on his discipline), has been awarded 10 fellowships and grants for excellence in photography from the Ohio Arts Council and the Greater Columbus Arts Council and has achieved international recognition for his work. Friedman is particularly proud that prominent art historian and author Dora Apel described his project, “12 Nazi Concentration Camps,” as “arguably the most significant body of photographic work on the concentration camps in the post-Holocaust era.”

Thanks so much for taking on the challenge of being the Ohio States Project Editor! Can you tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography?

I experienced a dysfunctional, chaotic and, sometimes, fearsome family life, in which there was very little emotional intimacy or expressed affection. I felt abandoned as a child and profoundly lonely until one day when I looked through the viewfinder of my family’s Kodak Brownie Hawkeye camera and suddenly the world appeared balanced and harmonious. I was four years old when I made my first photograph. Since then, I have felt connected to the world whenever photographing and making prints; decades later, photography continues to nurture and provide stability for me.

How did you find the Ohio photographers you are featuring this week?

Because I have spent the majority of my life in Ohio, I have been aware of many of the talented and important photographers working here. And the Ohio Arts Council was uncommonly generous in allowing me to review the work of applicants from recent years for its Individual Excellence Awards in Photography. These awards recognize the exceptional merit of an Ohio artist’s past body of work and celebrate the creativity and imagination that exemplify the highest level of achievement in a particular artistic discipline. It was a pleasure to see the synoptic diversity of the work of Ohio photographers. Between my personal awareness of photography in Ohio and the Ohio Arts Council’s support, I selected four practitioners whose work evidences profound and authentic engagement with the medium.

Is there anything that defines or inspires photography in Ohio?

Some of the best photography being made anywhere can be seen in Ohio. There are legions of immeasurably talented photographers who have chosen to make Ohio their home rather than, say, relocate to New York or Los Angeles because of their love of the soulful, genuine nature of Ohio.

Today we are featuring two of your many, many projects, how have you managed to be so prolific?

An insatiable curiosity about the unpredictable, elastic and chameleon-like nature of photography and an old-fashioned Midwestern work ethic have led to my prolific output of work during the past six decades. Earlier in my life, I was consumed by tennis, playing with commitment in childhood and as a teenager and as a varsity player for Ohio State University. The endless hours of practice over many years needed to refine my tennis skills provided a framework for my later passionate, exhaustive engagement with photography.

I am restless, by nature, and have always considered each new project as the opportunity to begin anew in exploring photography, without feeling any need for each project to be directly connected in form or content to previous work. I love that my archive of projects is eclectic and varied in its formal and conceptual strategies; in my view, despite differences in approaches, all of my work still is connected by formal and conceptual rigor and autobiographical elements.

The work from “Unmasked” feels to be contemporary, yet it was made over 40 years ago…I feel like art is cyclical and many of the approaches from the 1970’s and 1980’s are rearing their heads again…do you agree?

I agree – in fact, approaches from the 1870s and 1880s, and even earlier, are reappearing – but I have some reservations. As a vehement response to the radical digital revolution, a number of photographers recently have embraced analog film cameras and resurrected 19th century processes ranging from daguerreotypes, to work with wet-collodion imagery and ambrotypes, among many others, to experimental analog darkroom investigations. While there is some exceptional work being done using both antique and more recently abandoned processes and materials, in my view there has been an unfortunate tendency to celebrate some artists or their work merely because of the use of these anachronistic techniques and not for the art’s inherent merit. Current work using older technology or approaches has value only when it does not allow process to overwhelm ideas and substance.

And finally, describe your perfect day…

My perfect day would be photographing in Iceland.

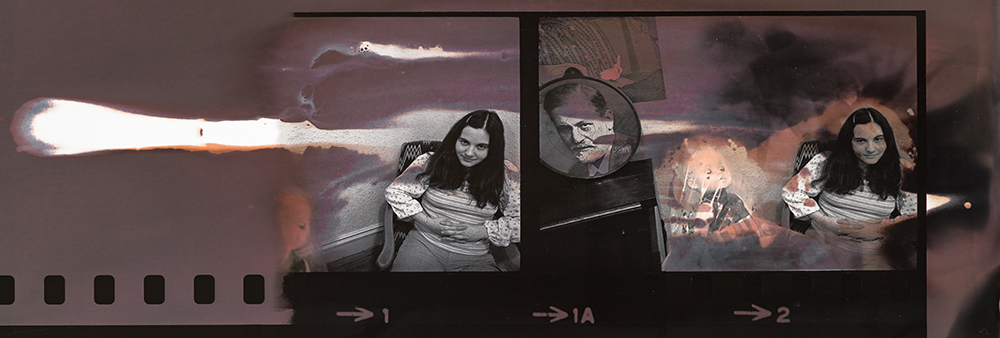

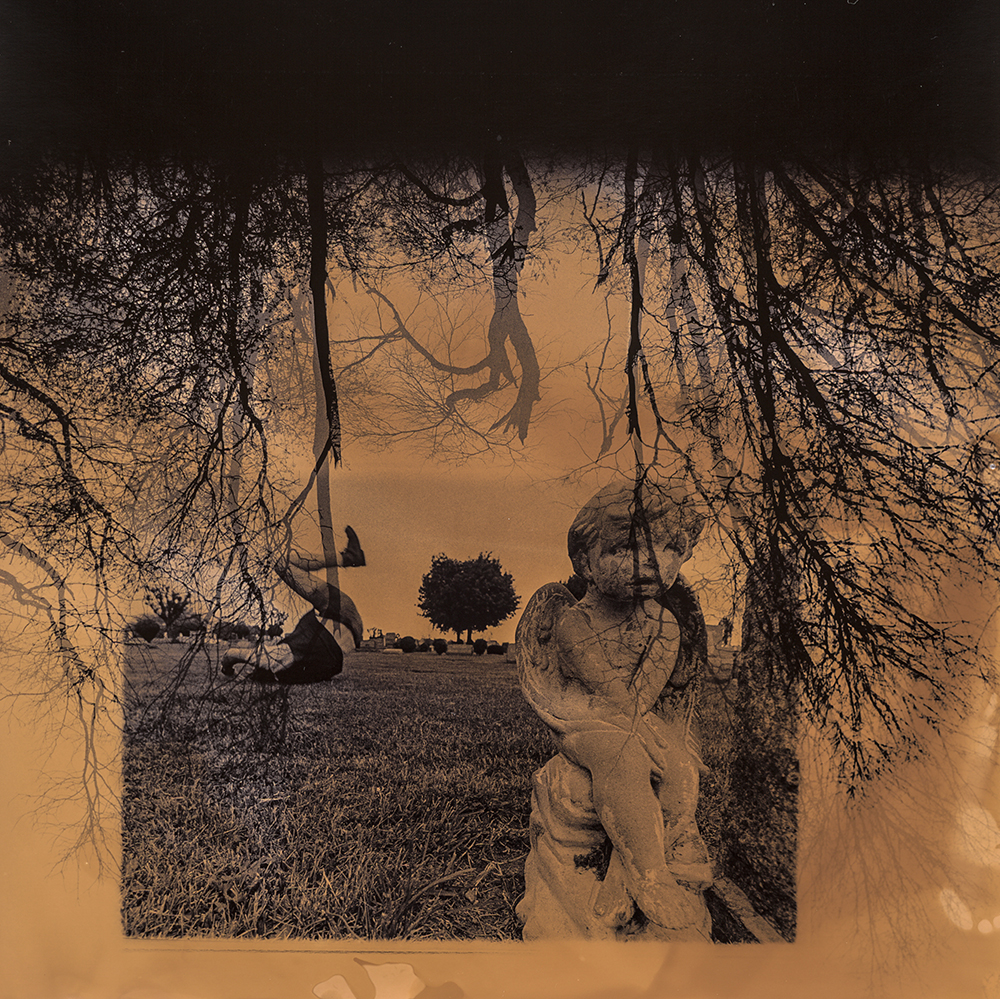

Unmasked

All of the works in Unmasked were made between 1970 and 1975 in a chemical-based, analog photographic darkroom using fiber-based, black and white, chlorobromide photographic paper processed in traditional chemistry. Employing various experimental procedures with readily available materials, I sought to unmask the hidden potential for releasing color responses on conventional black and white photographic paper. I have also included photographs from the series that are absent of color because I consider them to be central to this project and because their formal and conceptual strategies are compatible with the other works in Unmasked.

The works in Unmasked were made during a period of profound personal upheaval, including the sudden death of my father while playing tennis at age 47. The majority were made during my graduate studies with Minor White at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While a number of other students made photographs that imitated his approaches, I determined to distance my photography from Minor’s and used strategies in Unmasked that I believed were quite different from what could be seen in his work. Viewing these photographs now, though, I realize that while they do not look like Minor’s pictures they undeniably share his work’s passion for self-discovery and its highly charged, raw emotion.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026