Raymond Thompson Jr. and Wendel White in Conversation

Today we share a conversation with two artists who work with Black histories, Raymond Thompson Jr. and Wendel White, as they discuss their journeys and projects.

Raymond Thompson Jr. is a freelance photographer and multimedia producer based in Morgantown, WV. He currently works as a Multimedia Producer at West Virginia University. He is also pursing an MFA in photography from West Virginia University. He received his Masters degree from the University of Texas at Austin in journalism and graduated from the University of Mary Washington with a BA is American Studies. He has worked as a freelance photographer for The New York Times, The Intercept, NBC News, Propublica, WBEZ, Google, Merrell and the Associated Press. IG @raythompsonjrphoto

Wendel A. White was born in Newark, New Jersey and grew up in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. He was awarded a BFA in photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York and an MFA in photography from the University of Texas at Austin. White taught photography at the School of Visual Arts, NY; The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, NY; the International Center for Photography, NY; Rochester Institute of Technology; and is currently Distinguished Professor of Art & American Studies at Stockton University.

He has received various awards and fellowships including a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in Photography, three artist fellowships from the New Jersey State Council for the Arts, Bunn Lectureship in Photography, Anne Reeves Artist-in-Residence (Arts Council of Princeton), and grants from Center Santa Fe (Juror’s Choice), the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, and the New Works Photography Fellowship from En Foco.

His work is represented in museum and corporate collections including: Duke University; New Jersey State Museum; California Institute for Integral Studies; Graham Foundation for the Advancement of the Fine Arts, Chicago, IL; En Foco, New York, NY; Rochester Institute of Technology; The Museum of Fine Art, Houston, TX; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL; Haverford College, PA; University of Delaware; University of Alabama; and the NYPL Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NY.

White has served on the board of directors for the Society for Photographic Education, three years as board chair. He has also served on the Kodak Educational Advisory Council, NJ Save Outdoor Sculpture, the Atlantic City Historical Museum, and the New Jersey Black Culture and Heritage Foundation. White was a board member, including three years as board chair, on the New Jersey Council for the Humanities. He currently serves on the New Jersey Memorial Martin Luther King Jr. Commission and the advisory boards of the Atlantic City Arts Foundation and State of the Arts NJ.

Recent projects include; Red Summer, Manifest, Schools for the Colored, Village of Peace: An African American Community in Israel, Small Towns, Black Lives, and others. IG @wendel.white

Thompson: With your project manifest you recreate a personal archive from other’s archives. What is the impact of this? Why is it important for African American artists to work with historic materials in this way?

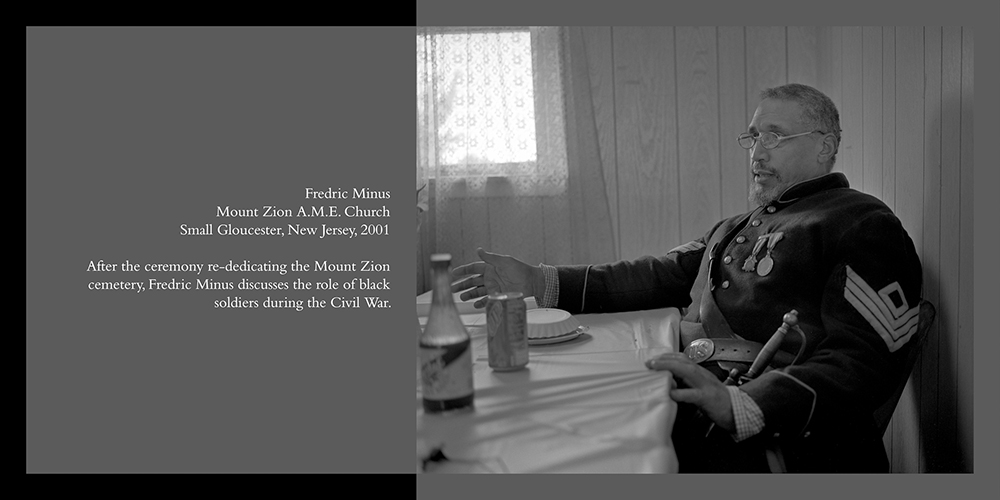

White: From the beginning of the Small Towns, Black Lives project, I was drawn into archives as a way to recover the lost narrative of a Black settlement in southern NJ. Beyond the information and stories held within the archive are the residuals of past lives and the broader narrative of African American life in the U. S.

Thompson: I was an American Studies major as an undergraduate. From my studies, I was left with this deep understanding of the importance of studying historical systems. I begin thinking of America’s complex racial caste system as a system of oppression that is very hard to see at the micro level and that requires examining from a macro level. Do you resonate from understanding black history from this angle? How has your connection to the field of American Studies influences your art making practice?

White: Historical narratives and historicity emerged organically in my work. It came about through many conversations with the individual participants in my work as well as discussions with artists and scholars. There is no doubt that I am working on these questions from a different viewpoint, gathering many small fragments to reveal the structures beneath the surface as well as a perspective seen from above (systemic racism). It may seem inefficient, something like starting a jigsaw puzzle without knowing the picture, but in this case I do know that the picture will be part of a particular set of concerns.

Thompson: What is it about the period of African American history from Reconstruction to the Civil Rights movement? I believe both of our art practices have focused on this time?

White: I became interested in the efforts to suppress any movement toward racial equity and to solidify the institutionalization of white supremacy. The dismantling of Reconstruction advancements, prisoner leasing, Plessey v. Ferguson, Wilmington’s successful insurrection to overthrow a multi-racial government (see http://wilmingtononfire.com), lynching, Red Summer, Tulsa, Rosewood, segregation and the school-to-prison pipeline to name a few of the complicated ways in which race based competition has played out in the U.S. during this timeframe. These and many other issues have been core concerns for black photographers for many decades, directly or indirectly as told through the stories of our communities.

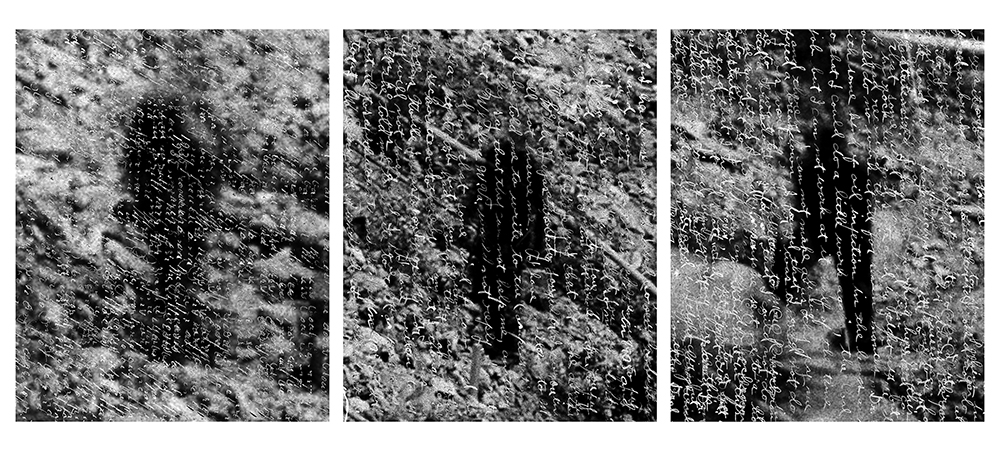

Thompson: I often struggle to integrate historical text into my work. How do you approach using text in your art-making practice and why is it important to focus our attention on words?

White: Text has been present in my work for more than three decades (first exhibition was “Eight Photographers” curated by Deborah Willis in 1990). The textual elements have always been mechanical (initially typeset and later digital) rather than mark making, so much of the work that influenced me was published such as Roy DeCarava’s Sweet Flypaper of Life or Wright Morris’ The Inhabitants. I also worked for a year creating a photographic archive for Essence magazine. The result has been that the text and image in my work are often derived from the influence of published works and the printed page.

White: Often in my work, one project leads to another, and over time, they emerge as a set of interconnected concerns. As you indicated above, perception of the macro-level system is critical. How do your various projects address this issue? If they are linked, are you finding the connections through your research?

Thompson: I think that there are connections in my work that I didn’t realize at first . The archive has emerged as a major influence in my photographic practice. My first attempt at making more experimental work was my project Imaging/Imagining. In that body of work, I tried to address the problem of African American exclusion from the visual archives surrounding America’s wild spaces. I did see many images of blacks in the wild spaces, so I made some. It was an attempt to fill in the visual narrative of an experience that I knew existed. With my next two bodies of work Appalachian Ghost and the trauma of white light I continued to follow my interest in the archive by actively engaging with and remixing the primary source materials I discovered.

(follow-up: do you know Glynnis Reed’s work? )

White: You are currently pursuing an MFA after an undergraduate degree in American Studies and a graduate degree in Communications. I have recently had great conversations with Ron Tarver and Don Camp, both are black photographers that began their careers as photojournalists later migrating their storytelling backgrounds into more specifically fine arts practices (MFA’s). What drew you towards the MFA as a skill set in your artwork?

Thompson: Photojournalism was the absolutely best training ground to be becoming a well rounded photographer. You get to shoot everything, from sporting events and funerals to politicians and state fairs. But, one thing that was missing for me was that photojournalism focused on the present moment. My time as an American Studies major really taught me how complex American history and culture really were and that African Americans were in many ways the backbone of this civilization. But, you would never know that from the history that I learned in high school or what I was seeing in pop culture. I figured out that I needed a way to look into the past and also look into the future. Photojournalism was too limited to help me do that. So I went to art school looking for an answer.

Thompson: Your early work from Small Towns, Black Lives focused on the quotidian of black life. It is the kind of black spaces that traditional American media and culture tended to downplay, favoring the more sexy images of black life on the sporting field, on the performance stage or in a drug ravaged ghetto. What role do you think historical images from the African American quotidian have to play in contemporary American life?

White: These images are part of the “racial competition” I referenced earlier, in that, at the contemporary moment there is an ongoing struggle to define the narrative of the American story. There are so many great scholars and artists working to fill in the gaps and correct the misconceptions of the historical record in this country. At the time (Small Towns, Black Lives project began in 1989) I was particularly aware of the sharp contradiction between the majority of media representations of black communities and the communities I was photographing as well as the communities of my childhood (the Cobbs Creek neighborhood of Philadelphia in the 1960’s or the Oranges—Orange and East Orange) in the 1970’s. A Utah school is allowing parents to “opt-out” of Black History month for their children and all of the push back that has come as a result of the 1619 Project and its accompanying curricular materials is evidence that information about the integral role of African Americans is still perceived as diminishing the central European narrative of America. Telling the stories of ordinary (which in the context of enslavement is quite extraordinary) black lives is still perceived as radical and threatening to the ideal of American exceptionalism.

Thompson: What do you hope the viewer will take away from your combination of image and text from your Red Summer series? Do you feel like this work resonates with our current political and social moment?

White: This work is part of a broader set of concerns in my work regarding the African American life in the U.S. As a result of the accumulation of projects and portfolios, the ongoing pattern of repeated violence toward the black community is one feature of my work. I am marking the other narratives of resilience and agency that emerge as a response and inspite of the various forms of oppression. So, yes, I am certain that we understand the contemporary moment in the context of the historic patterns of abuse. This is a critical point, black anger and frustration are not isolated from the history of the U.S. In the Red Summer works I continue to respond to the past events that have shaped the current moment.

White: Looking at your Dust and Trauma of White Light series (which are remarkable) I am drawn to thinking about the recent discovery of a mass grave connected to the prisoner leasing system that operated between the Civil War until WWII (in its most brutal form) only to be replaced by other oppressive policies in the justice system. Have you been thinking about the role of labor in your work?

Thompson: I have been thinking about the role of labor in black life as it relates to the how and why African Americans have been included in America’s historical visual archive. The Dust series from Appalachian Ghost is a good example of these thoughts. On one hand, I wanted to remind myself and my audience that it was African American labor that built this country. But on the other hand, I wondered if I was drifting too far in the direction of the black working body as iconic. I asked myself if using these iconic working black bodies is somehow complicit in the replication of visual stereotypes. I don’t have an answer yet to that question. I think the trauma of white light is trying to have a different conversation. I want to connect the cash crops that built American wealth with the visual stereotypes that are the backbone of the American narrative.

Thompson: Since we are on the subject of the iconic, I was wondering if you had any thoughts on the use of iconic imagery of African Americans in photographic history?

White: This causes me to think of the work of Terry Boddie, Lorna Simpson, Dread Scott, Carrie Mae Weems, Ron Tarver, Clarrisa Sligh, Lynn Marshall-Linnemair, Albert Chong, Stephen Marc, and Carla Williams. Central to this practice is the scholarship of Deborah Willis, Sarah Lewis, Teju Cole, Kelli Jones, Thomas Allen Harris, Leigh Raiford, and many others

Thompson: From my perspective, it feels like marginalized artists are producing work to counter historical archives at an increasing clip. From your experiences working with this subject matter what advice would you give to us new to working with history and archive materials?

White: As I indicated earlier (Utah school creating the option to participate in Black History month), we are undoubtedly in an era of increased repressive activity with regard to Black Lives and the narrative of the American story. These efforts are often painful and difficult for us as artists and as members of the black community which has endured so much. Brian Stevenson’s work on lynching is a particular example of that duality. Archives preserve things of value and are also repositories of painful evidence. The engagement of artists in the archive will bring new perspectives to the understanding of these materials.

Thompson: Is there a role for Afrofuturism thinking in archival and historically based photographic work?

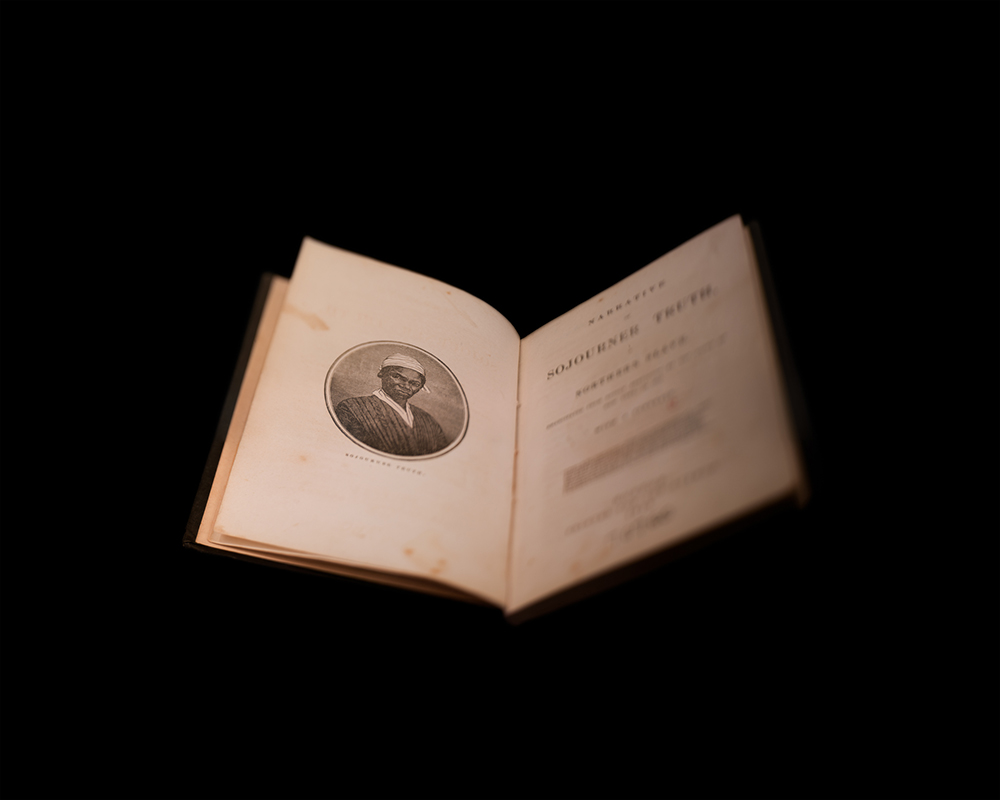

White: Without a doubt there are many historical figures that have used the idea of inventing a future that did not exist, the entire effort of African Americans to free themselves from enslavement, was a form of Afrofuturism. Colson Whitehead leverages this notion in his novel Underground Railroad. Certainly Frederick Douglass’ use of the then new technology of photography (extensively) was also an expression of the concept. The manner in which he used the photograph and constructed an identity through the use of the photograph was at the time revolutionary (see Picturing Frederick Douglass). In many ways this question is the other side of the concern about the archive. If seeking the archive is a means of reframing the past narratives about black life and culture, Afrofuturism seeks participation in the construction of new stories for the human future, resisting the already long history of imagining a most white future (especially in science fiction narratives). Looking at the archive and the historic use of photography (among other technologies) are long established activities throughout the diaspora that have imagined and used technology as a means of gaining access and agency in a “better” future.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026