Focus on Ecuadorian Photographers: Isadora Romero

©Isadora Romero, PROLOGUE. Of a hundred pieces of land in Paraguay, 94 are used to grow transgenic monocultures sprinkled with agrotoxics and none of these products feed local people. Only 6 pieces of land are used to grow local products that feed people in a sustainable way.

This week we are featuring the work of Ecuadorian Photographers. Ecuador straddles part of the Andes Mountains and occupies part of the Amazon basin. Situated on the Equator, from which its name derives, it borders Colombia to the north, Peru to the east and the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west.

Isadora Romero is an Ecuadorian freelance visual storyteller based in Quito. Her work focuses on human identities, gender and environmental issues. Co-founder of Ruda Colectiva, a Latin American woman and non-binary photographers collective. She has exhibited her work in the Americas and Europe. She was selected for the Magnum Foundation’s Photography and Social Justice Fellowship 2021 and the World Press Photo’s Joop Swart Masterclass 2020. She was invited to the 2019 Antarctic Artist in Residence at INAE. She won individually and collectively two National Geographic emergency funds as well as a Magnum Foundation emergency grant for Covering Covid 19 related Issues. Winner of the second place in environmental issues at Poy Latam 2020 she also won an honorable mention in the 2019 Photobook contest. She is the winner of the Photojournalism for Peace Prize and the Ecuadorian Culture Grant in 2017. She is the finalist of the Ilia photo contest of Rome, as well as of the Magnum Foundation’s Inge Morath 2017, and wins an honorable mention in the Fotodocument’s Marilyn Stafford award among other recognitions. Her multimedia works have been projected in various countries of America, Europe and Africa between 2015 and 2021. She has work with media outlets and NGOs around the world. She has also been a tutor in Latin América being invited for the Colloquium of photography in Mexico, and to direct a photographer’s residence in Chile, 2019. She is the leader of the Women photograph chapter in Quito. Member of Women Photograph, Diversify Photo and the everydayprojects.

Follow Isadora Romero on Intagram:@isadoraromerophoto

©Isadora Romero, Saturnina Almada (Ñanina) is one of the main seed guards of Edelira. She inherited the ability for collecting, planting and labeling native and traditional seeds from her mother. She knows that her work is important and she hopes that one of her children will maintain this tradition.

Ra’yi

Ra’yi (from the Guarani language that means seed) portrays, in a subjective and symbolic manner, women peasants who fight the inequality of agricultural business in Paraguay, one of the most most inequitable territories in Latin America with regards to land distribution: 2.5% of the wealthiest population owns 85% of the productive land. The peasants use only 6.4% of all arable land. This is not enough to supply crops for the whole country. The few who can produce have great difficulty in selling products because there are no adequate roads or transportation.

However, there are particular initiatives and social organizations that fight to resist from within: seed guards that preserve native seeds and volunteers who help empower and organize women to grow and distribute agro-ecological products in Asuncion, the country’s capital.

For me, it is fundamental to talk about this problem away from victimization, showing examples of resilience. Using various narrative tools, I wanted to make the statistics visible but also portray the deep-rooted relationship that women have with the land, the crops, the territory, their identity, the care they have and the understanding of the living cycle. Ra’yi is a tribute to those who resist and fight for a better future.

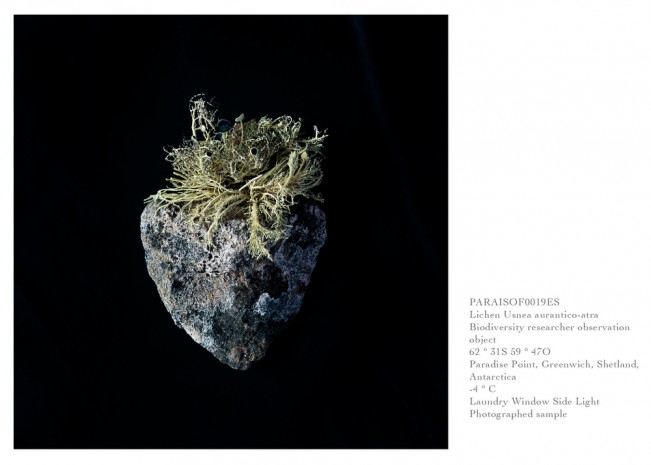

Estremophiles

This is a visual story that contains photographs and objects obtained during the XXIII Ecuadorian Antarctic expedition. This project explores the human presence on the white continent. Bringing out the absurdities and contradictions of the human species.

At a time when the need for conservation of the planet is being urgently discussed, but the actions needed directly contradicts the geopolitical and economic interests that prevail in human societies that abuse natural resources, it is strange to think of a utopian and mysterious continent like Antarctica. A place destined merely for scientific study, but where nevertheless, many exploitations interests are latent. This space of which we have widely known its landscapes and fauna, in our imagination the human species does not appear as one that arrives by seasons and intervenes in its environment. As part of the scientific commission of the XXIII Ecuadorian expedition to the continent, I decided to carry out an artistic-anthropological-scientific study of the human species, in turn questioning the hegemony that Western science has in our collective imaginary.

©Isadora Romero, Zulma Vega (Ñazunni) in her garden. In her farm she has everything she needs to feed her family, she knows all the plants that act as natural fertilizers for the land, also those that give rise to pests. Its orchard full of diverse plants everywhere differs a lot from the apparently perfect plantations of the adjacent monocultures.

©Isadora Romero, Romi Cabrera is one of the creators of the Peasant’s little market, an initiative that allows farmers to market their organic products in the city. She joins these bridges with love and dedication but she considers herself just as a volunteer. For a long time she did not want her image to identify the project but the peasant producers.

What was the first image or circumstance that motivated you to photograph?

I don’t really know if it was an image. My path with photography began when I was a child and wanted to make movies. While studying film, I took a photography class and liked it better. I noticed that in order to make films I needed a lot of time, people and money. Whereas with photography, it was just my camera and I.

©Isadora Romero, One of the producers of the “Peasant’s Little Market” who have organized to grow their gardens and with the help of this initiative can market their products. Thanks to the profits that this generates, they have been able to leave abusive jobs, have more independence and help their families.

Which fields and people have inspired your photographic work?

I’m inspired by film. My mom is a journalist and my dad is a communicator and since I was young I had the opportunity to learn about different languages, narratives, rhythms, etc. My parents’ stories always inspired me! Regarding literature, I was inspired by short stories by Latin American authors like Pablo Palacios, Cortázar or Borges. However, I noticed how all my influences were white men from other continents and it was important to find Latin American women too. That is how I came across Graciela Iturbide, Ana Casas and many other photographers that I deeply admire, especially from Mexico. I have always been interested in Cristina de Middel’s work. Now, there are also contemporary photographers whom I admire, colleagues like Yael Martínez, Coral Carvallo or Luján Agusti. I like observing artistic processes.

How do you create a visual narrative?

While you discover how you like to photograph, your aesthetic and what attracts your attention, it’s important to know what you want to say. What is it that moves you? Especially for your own projects, freedom and independence are wonderful but you’ll have to deal with them for a while.

Every time I approach a new theme, I ask many questions and I need to pose those questions to generate them in photographs. The projects that thrill and motivate me are the ones that pose questions and allow me to add my experience to unravel them. You don’t really need answers, you’re not gonna look for answers with your camera. Nor is it necessary for you to know what to represent and have people know your stance. I believe it’s better to draw from vulnerability and acknowledge that you do not know and will never know everything.

©Isadora Romero, One of the main reasons why the products of the field can not be commercialized is because there are no good roads and highways that connect the city with the countryside. Except for the roads that reach the largest soybean plantations, the rest of the roads are still dirt and during the rainy season it is impassable.

©Isadora Romero, A woman shoe dries out at Ñazinni’s house in Edelira, Paraguay. Women empowerment is very important for both of the initiatives showed in this project. Conamuri organization as well as the peasant little market both believe that changing how women get involve with the land can change the whole community.

How can we address violence in photojournalism without victimizing those who are involved?

As an image creator and a privileged person whose voice has the capacity of narrating and being heard, I am conscious of how harmful that voice can be. This has been important to me since I began studying film. Precisely, what you have mentioned about further victimization is a grave issue that has recently been acknowledged. First, I began telling stories that were of no interest to the media and that meant that I had the possibility of broadening my narratives. Namely, Latin America has always been portrayed as poor and violent. How can we change that narrative? How can I speak about the other aspects of people’s lives? We obviously have a terrible amount of violence and we have it marked on our bodies but we can talk about that from a different perspective. There is no recipe but I think it arises from understanding people’s complexity and not being simplistic. What happens to those people once you show your photographs?

I think I cannot, strictly, be a photojournalist because I am not brave enough, I am too sensitive. It has been important to take the time to know whom I photograph, who I am collaborating with and so we create stories together. I think that’s a fundamental step towards not victimizing. Victimizing is easy, there is a power structure that allows it. Once you break that structure, everything becomes more human. Seeking collaboration is important, not photographing from an omnipotent voice.

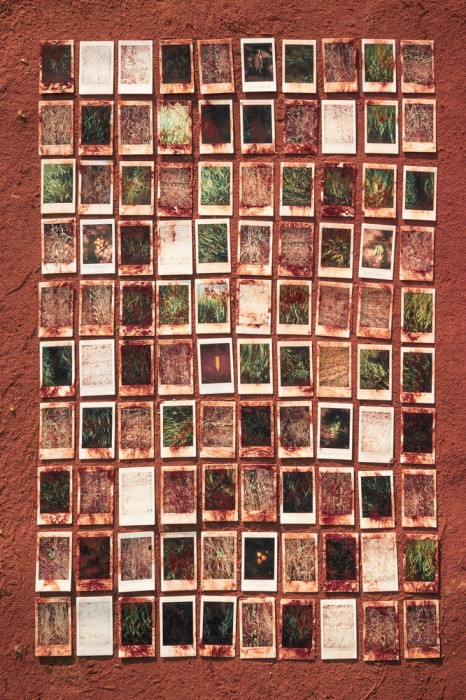

What has been your process when intervening documentary photographs for your series Ra’yi and Hebra?

I think of language when I think of other means of narrating. How can we form an image? I remember questioning formats when I was studying. Whose idea was it that film should look rectangular (16×9)? I understood that language is a preconceived notion. We live in a world in which we can tell a story in a million ways, we have every possible technological device available, we even have ancient technology. If we have a box full of crayons, why use only one? Thus, when I’m working on a project, the photographer’s gaze is no longer sufficient to tell the story. Namely, for Ra’yi the statistics were too striking. We are used to seeing statistics as numbers, they are hard to imagine or understand their scope in reality. The food that sustains the Paraguayan population is grown only on 6% of their territory. The rest of the land is monoculture and transgenic farming. Paraguay is an extremely fertile and wonderful country but there are many social issues that stem from the territory. How can we make statistics visible? I usually take a lot of equipment with me when on assignments. On that occasion, I took my instant camera and I found my way into the soy and wheat fields in order to make statistics visible.

Hebra was a similar process. My colleagues and I were tired of the development being one-sided and wanted a collaborative project, to reflect more before making photographs.We speak with people and listen, we build together. Projects are alive before they even come about, they guide me. The most important part of Hebra’s process was the healing ritual through embroidery on the images. We addressed important questions: What happens after violence? What are our healing systems? How have we healed since ancient times? Nowadays, during the pandemic, I’m working on an analog project. I was fed up with the digital world and being in front of a screen and wanted to experiment with my hands. I started making antotypes with fruit juice, I needed to generate images in which my body was involved.

Each project dictates which tools I may use in order to expand what I can say through the images.

©Isadora Romero, On each Antarctic island there is a structure with arrows that point the distance between that exact point on earth and different places on the planet. Here is this structure covered in frost from the night before. Greenwich, Shetland Islands, Antartica

©Isadora Romero, A complete flotation system hangs alongside the Achilles ship that transports expeditionaries from their stations on the Antarctic Peninsula back to the American continent after the southern summer is over.

How have you faced the dangers that derive from your profession?

When you are on-site, you must be intuitive, you must be able to develop your intuitive capacity. Curiosity leads us to dangerous places but one must be cautious and prevent unnecessary risks. Honesty and transparency when addressing another person’s issue is essential. When I covered the strikes in October, I was in danger. I confronted violence and it resulted in psychological scars, this happens with photo journalists. Now that I participate in RUDA, a collective that I work with, it is like therapy. We have a monitoring app and we give each other advice on how to develop projects. I am only talking about my own experience, I know of other colleagues that are going through very vulnerable times.

©Isadora Romero, A colony of chinstrap penguin chicks pass by an old structure at the Chilean base Gabriel Gonzales Videla on the Antarctic Peninsula. This Station only functions during summer and was build in 1959 over near penguin colony, something that is prohibited now.

©Isadora Romero, Biologist Tania Oa on a snowy day next to the Pedro Vicente Maldonado station’s laboratory located on Greenwich Island on the Antarctic Peninsula. She has traveled five times to Antartica to develop an investigation about lichens.

©Isadora Romero, An iceberg several kilometers long floats in the then calm waters surrounding the Antarctic peninsula.

What does it mean to be a woman in Ecuador? Have you felt excluded because of being a woman?

I believe that there are limitations with being Latin American and making a living through photography. One of the biggest issues when it comes to work is not living precariously, a constant struggle for me. Also, I noticed how I am an incredibly privileged Ecuadorian citizen and that has always opened many doors, one ought to be coherent with that reality.

I am interested in educational processes, workshops, womens’ organizations, broadening my tools and debating about communication processes. These go hand in hand with telling stories, and Ecuador is an endless source of stories. Once I moved to Argentina, exhausted from living in Ecuador, I noticed I had no stories to tell. As soon as I came back, I began narrating and connecting my family’s legacy and understanding my ancestors as narrators. Further, when thinking about gender, I know I have less access and I am questioned because I am a woman. I am subject to danger and I must transform my attitude to look less vulnerable. Gender permeates every action.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Juliette Ludeker: Somewhere You Can Never GoFebruary 16th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026