Kai Yokoyama: The day you were born, I wasn’t born yet

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series The day you were born, I wasn’t born yet by Kai Yokoyama.

Kai Yokoyama is a photographer based in Tokyo, Japan. Starting out as an architecture student at Saitama University, he switched his major to photography and completed his studies at Tokyo College of Photography. He has traveled the world photographing refugees, children with disabilities, and victims of terrorism. In recent years, having lived abroad, he has been photographing foreigners living in Japan. His works have been published such as The Washington Post, Marie Claire Italy, and Foam Magazine. In 2020, he won first place in the LensCulture/Journeys series category. In 2021, Yokoyama’s work has been awarded Helsinki Photo Festival and shortlisted at Kolga Tbilisi Photo, Encontros da Imagem Discovery Award, and Portrait of Humanity. Also, he receives Carolyn Drake’s mentorship program in Magnum Photos in 2021. Recently, he has been shortlisted for the 2020 Emerging Artist Scholarship in Lucie Foundation, and he was selected for Photo Vogue Festival 2021. He is a member of Native Agency and Diversify Photo.

The day you were born, I wasn’t born yet

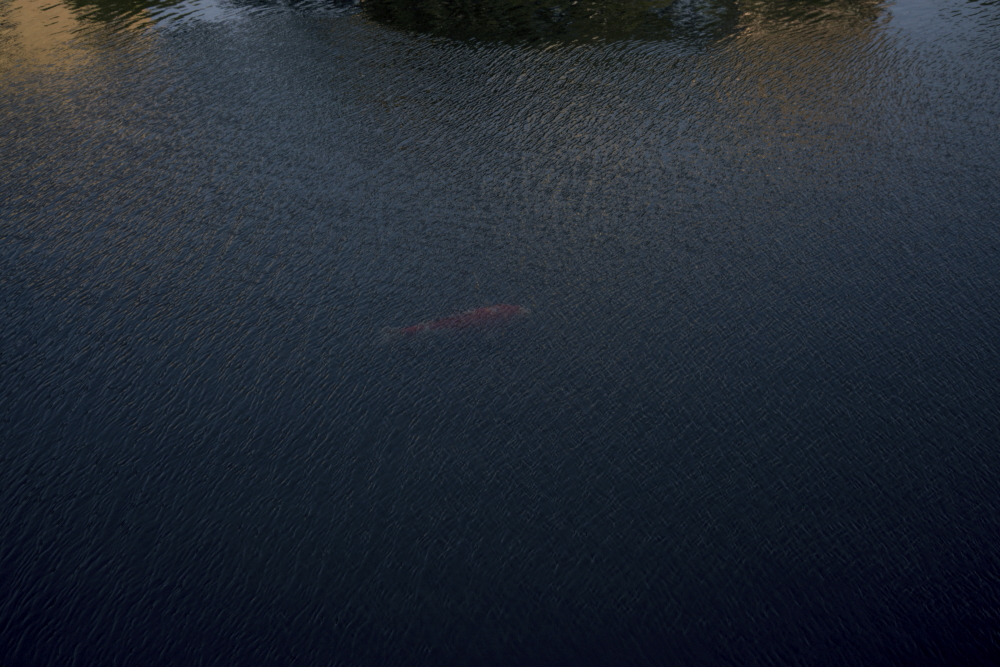

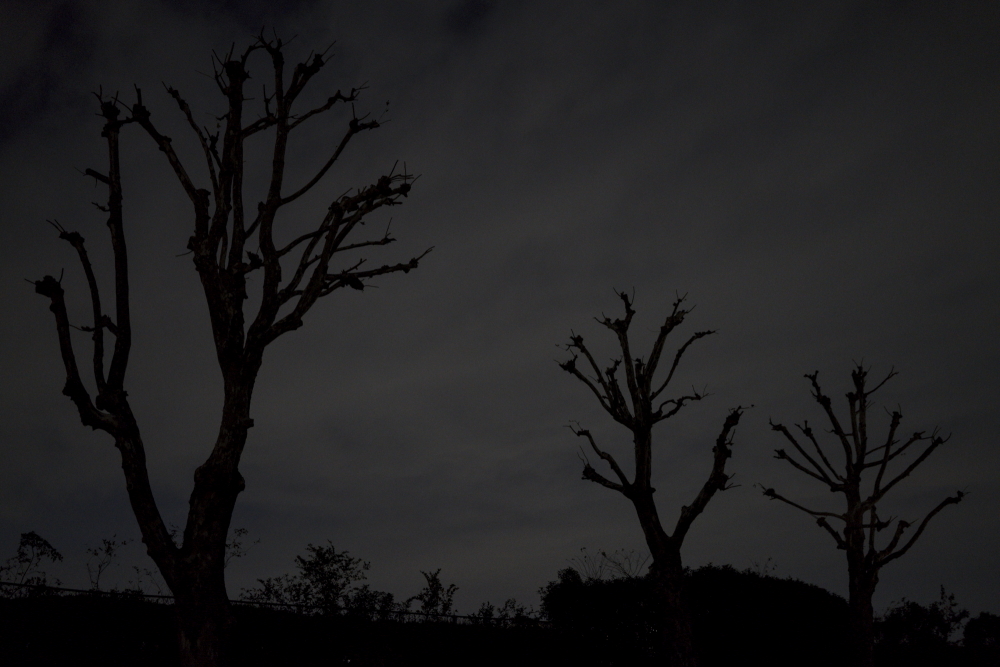

This is what I have to do now with my life. When this pandemic began in 2020, I lost control like people around the world. I talked with my parents more than ever and shared almost all my time with them. I searched for photos of my family in the past. I walked where my late grandparents lived and kept taking pictures. Then I tried to connect the present and the past. It was a kind of spatiotemporal movement as if I went back to where my soul had been. This April, my father said, “This year’s cherry blossoms don’t look beautiful at all.” I couldn’t help feeling the death from the scattered cherry blossoms. Cherry blossoms are drawn on the fighters, and the military song says, “Since we are flowers, we are doomed to fall. Let us fall magnificently for the country.” My grandfather went to the Pacific War. He came back and gave birth to the daughter who gave birth to me. I think it’s a miracle. There are countless reasons why I wasn’t born here.

Daniel George: I am curious about how this project came about. Prior to pandemic lockdowns, there must have been some thoughts/ideas mulling around in your head. What brought everything around to the point where we are looking at it now?

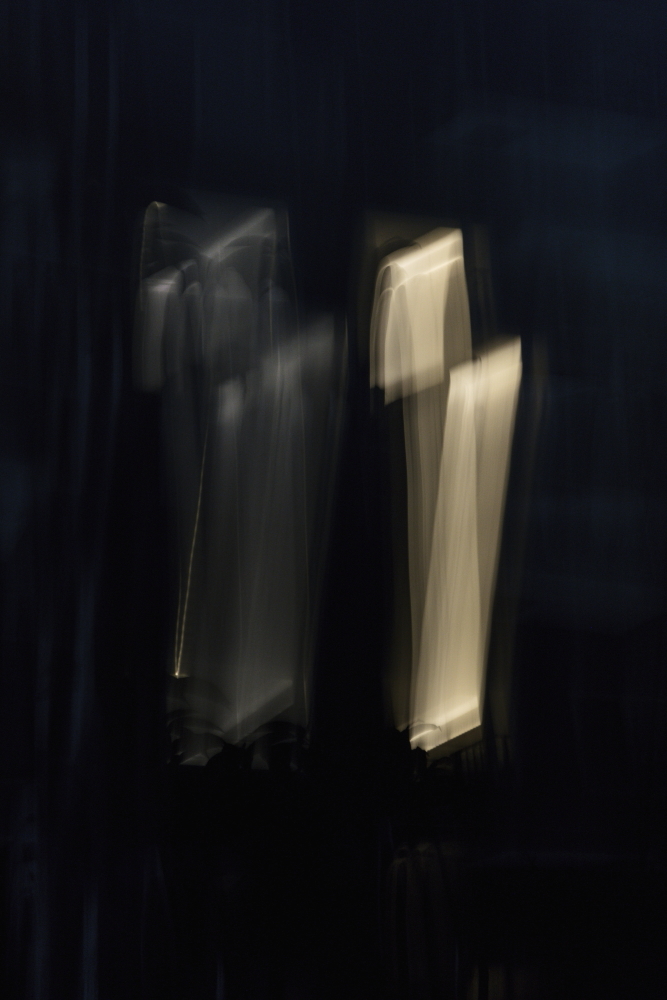

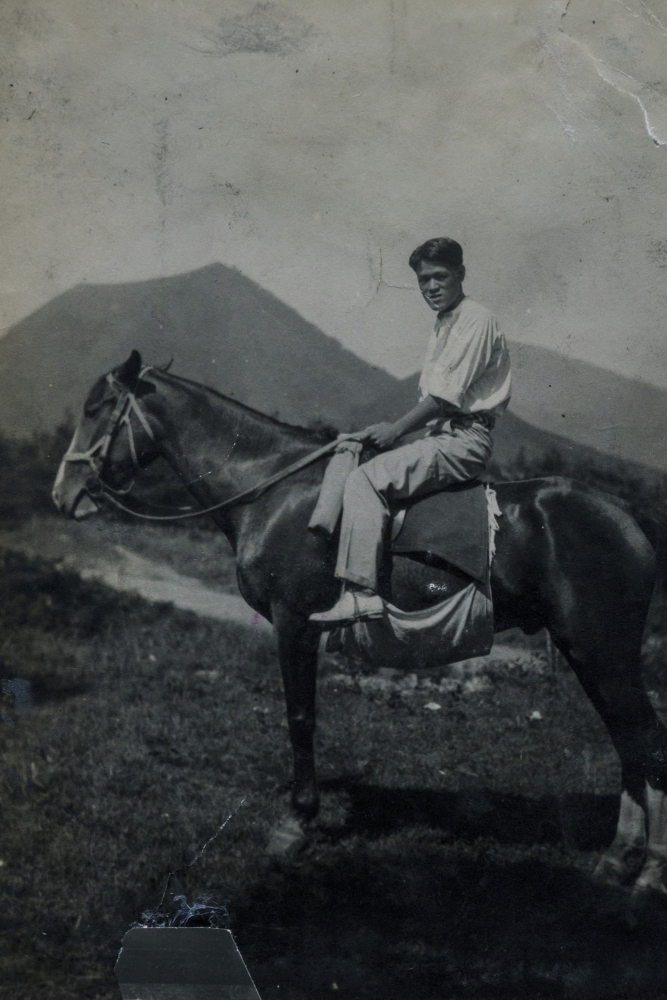

Kai Yokoyama: To be honest, before the pandemic, I had no idea for this work at all. The pandemic happened, and I was stuck in my home, taking pictures of the lights of the building across the street from my place. I had no idea what this was doing at the time, but I felt something there. When I think about it now, I feel that this light led me to something special. It was like a gateway to the past. And after that, I went back to my parents’ house. That’s the house I grew up in. I found a picture of my grandparents there. From there I went back to my house again, and fortunately the house where my grandparents and mother grew up was near my house, so I went there and took pictures. I didn’t think much before I took the pictures, I just took pictures of what I felt in the place.

DG: At the outset of the pandemic, you understandably turned toward family for solace. What caused you to delve beyond those around you, and to look toward your ancestors? What were you searching for at the time? And what did you find in their photographs?

KY: The reason was that I was truly grateful to my grandparents and parents for my being here and alive. When the pandemic happened, I didn’t know what it was, and I thought it was the fear that I might die that brought those feelings to me. What I was looking for was something to connect with me. What I was looking for was something that would connect me to myself, something that would connect me to my past. And from the pictures of my ancestors, I felt a sense of awe and gratitude. It is because of you that I am able to be here now.

DG: Could you expand on the title of this project? What draws you to find connections with those who preceded you?

KY: This title is taken from a book I was reading during the pandemic. The poet is Nakahara Chuya. What I try to do is talk to my parents and relatives, ask them about their past, and listen to what they have to say. It didn’t matter what it was, I just listened. Then I would ask more questions about what I was interested in. I think listening is a very powerful tool.

DG: I am interested in your consideration of place as a source of familial experience and memory. Why was it important that you visit and photographs these particular locations?

KY: It was because I thought there was something special about those places for us. The fact that my grandparents were there means that when I go there, I can picture them being there. I think that’s one way we can connect with them. For those reasons, I didn’t think too much when I was shooting and kept taking what I felt in that place.

DG: It is evident through your images and writing that this work serves to function as a reminder of both life and death—and to connect past and present. In what ways do you feel the photographic medium is best suited to illustrate these themes?

KY: A photograph becomes the past when it is taken. Therefore, I think that photography is a way to find a connection with the past and the dead. That’s what I think now.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Eliot DudikDecember 13th, 2024

-

B.A. Van Sise: On the National LanguageDecember 9th, 2024

-

The New Renaissance of Photo BooksDecember 7th, 2024

-

Smith Galtney in Conversation with Douglas BreaultDecember 3rd, 2024