Lisa Sorgini: Behind Glass

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Behind Glass by Lisa Sorgini.

Lisa Sorgini is an Australian artist currently residing in northern New South Wales (Bundjalung Country). In 2021 she had works selected as winner of the Lucie Awards Portrait Project and CCP Ilford Salon for ‘Most Critically Engaged’ image, recognised as a finalist in Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait prize(UK), as well as being shortlisted for the National Portrait Prize (Aus) and the Ravenswood Australian Womens Art Prize (Aus) . She was also nominated to participate in the Leica Oskar Barnack Award. In 2020 she was selected as winner of the Lens Culture Critics Choice award for her portraiture series ‘Behind Glass’ and had work recognised and shortlisted for a number of other national and international awards including the 2020 CLIP Award , 2020 Australian Photography Awards and the Head On Portrait Prize. Her practice engages with the relationship between mother and child, family and community and investigates the societal perceptions and constructs that are often vastly at odds with the lived experience. She is deeply interested in the way our familial relationships, particularly the mother role looks and changes over time. Her work has been exhibited within Australia and internationally as well as being published extensively worldwide, with recent interviews and features in The New Yorker, TIME Magazine, Creative Review and National Geographic. Lisa is represented worldwide by ACN Studio (New York) and is a proud member of Women Photograph. Behind Glass was recently published by Libraryman.

Behind Glass

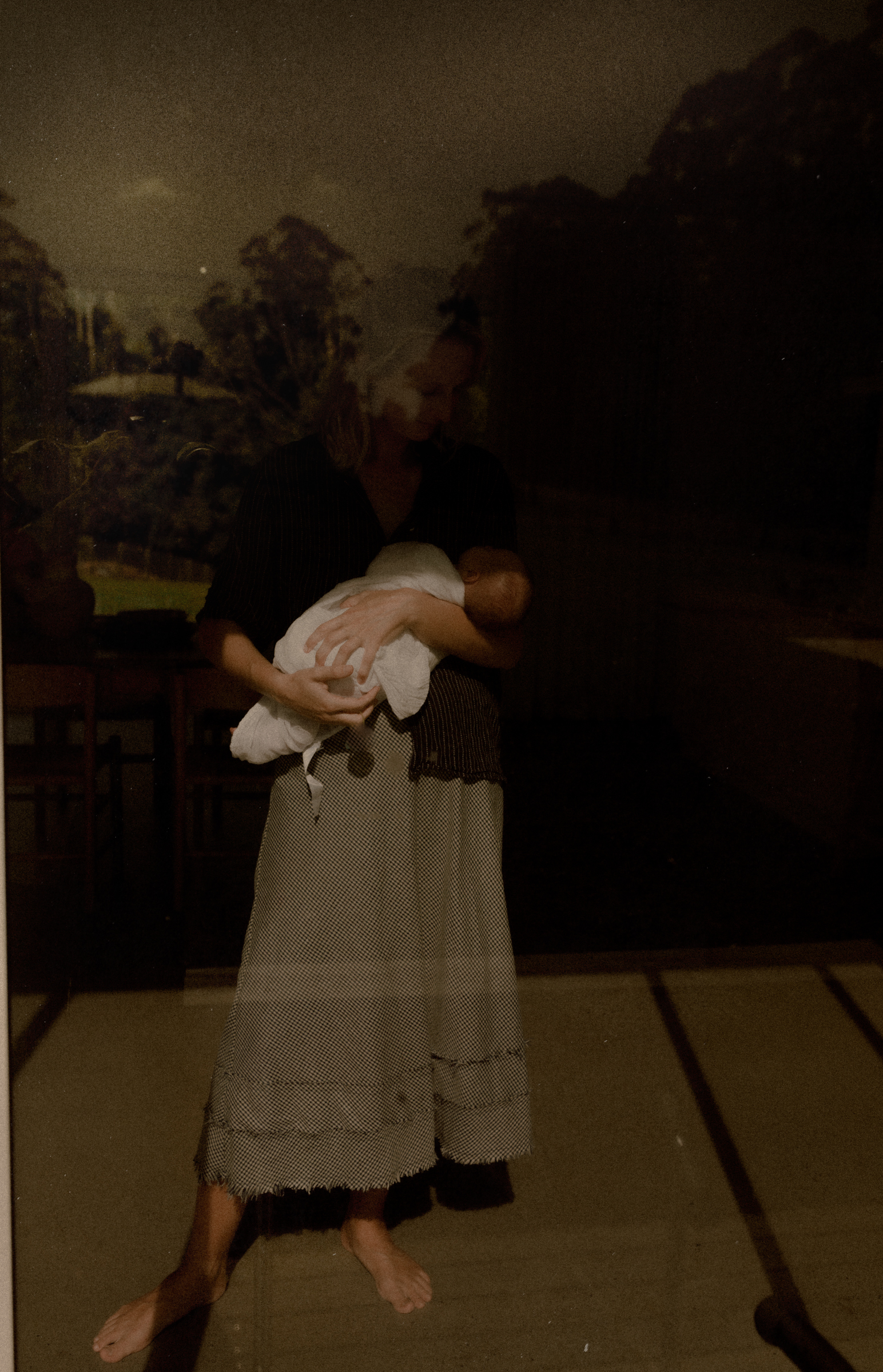

Behind Glass aims to offer a layered exploration of motherhood as shown during the months of the burgeoning COVID-19 pandemic, as unprecedented stay-at-home measures swept across Australia and the World. It stands as both a creative commentary and an important cultural record.

Born of the pandemic, shooting began for the series as the first stay-at-home orders came into force in Australia. Making portraits of those in her immediate community, It’s a body of work motivated by a need to make visible the unseen role of parenting during such isolation and one that evokes a spectrum of deep tenderness, tedium, quietude, love, frustration, fear, and despair. These works present the light and darkness of motherhood during these extended periods of lockdown. Behind glass, mother and child appear like living and breathing masterpieces – divine comedies of domesticity.

Whilst informing of a particular time, these images also speak more broadly of the maternal experience. It’s most blatant subtext is that of motherhood as contextualized within the modern western milieu; where women lie at the core of an intense inner world whilst continuing to remain begrudgingly detached from the outer as societal constructs and representations remain vastly at odds with lived experience.

Yet central to this story is also the concept of hope and connective awareness. Mothers joined through a collective experience. Through this work, the unseen is seen.

Daniel George: At what point after the COVID-19 stay-at-home orders were given did you decide to embark on this project? And what was it about the collective parenting experience at that time that captured your interest?

LS: Very early on at the beginning of the pandemic I had considered the project and contacted a few people locally who I thought might be interested in being involved.

I was also grappling with the feeling of being disconnected from my work due to the stay at home orders and sitting deep in the role of being mother to my two young children.

The biggest discomfort though was being disconnected from my supportive community, a network that is so crucial in early parenthood. The lockdown really brought that importance to the fore and made me aware of the value in this . As I worked my way through the project the feeling seemed to be mutual, each parent expressing that it had helped alleviate a sense of isolation and disconnect.

DG: I was drawn to the diorama-like quality of these domestic vignettes, and the parent-child narratives within the frames. Could you elaborate on how you view these as “divine comedies of domesticity?

LS: The act of child birth and its subsequent proximity to death as well as the act of raising a child are labors of sacrifice, surrender and deep love, and for me each of these images represent this in some way. The turn of a hand, tiny, often resistant bodies, the constant physical connection, women looking outwards while turning inwards.

The reference to The Divine Comedy, the spiritual journey of man through life and death in hell, purgatory and paradise was applied to subvert historically male sub-text to the current lived experience of women and mothers.

DG: I am curious about the ways in which you collaborated with your subjects for these photographs. Would you share a little about your process working with these people?

LS: Once I had organised the time with each subject I would arrive at their home and do a walk around the property to determine which window provided the best light to shoot with. From that point I asked the subjects to place themselves in front of that space and I would wait for the moment that felt right allowing them to interact and do what occurred naturally. Sometimes it was quick and for others I would move to a different location and work longer on achieving the desired image.

DG: Looking at other projects on your website, it is evident that you have a lasting interest in the mother-child relationship. Even projects like The Bushfire, the flood and the virus, which focus on the 2020 Australian brushfires, incorporate your experience as a mother. Would you talk more about the continued attention you give this perspective as a thread throughout your work?

LS: Delving into my own experiences first and foremost seems like the best way to make work that is honest and authentic. As the past 6 years have been informed so much by my experience of being a mother to my two young sons and losing my own mother it makes sense that this would permeate into my work.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026