Tokie Rome-Taylor: Reclamation

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Reclamation by Tokie Rome-Taylor.

Atlanta, GA based artist, Tokie Rome-Taylor, explores themes of time, spirituality, visibility and identity through the medium of photography. Portraiture, set design, and objects all are a part of Tokie’s photographic practice. She uses digital photography as her foundational medium, while also exploring cyanotype, and embroidery as a means to explore the layered complex relationship African Americans in the diaspora have with the western world.

Rome-Taylor’s series, “Reclamation”, was selected for PhotoLucida Critical Mass top 50 photographers. Rome-Taylor’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally with an exhibition record that includes the Chicago Museum for Innovation and Technology, The Southeastern Museum of Photography, The Griffin Museum of Photography, Stella Jones Gallery, SP-Foto SP-Arte Fair in São Paulo, Brazil, the Masur Museum, and Zuckerman Museum of Art, amongst others. She is a recipient of the Virginia Twinam Smith Purchase Award, adding her work to the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia as well as the Legacy Award, bestowed by the Griffin Museum of Photography. Her work is held in multiple public and private collections and was recently acquired by the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art. Her work has been featured in Atlanta Interiors Magazine, ArtsAtl, What Will You Remember and Feature Shoot Magazine. Additionally, Tokie is a Funds for Teachers Fellowship recipient, studying photography in Santa Fe, New Mexico and in San Francisco, California.

Reclamation

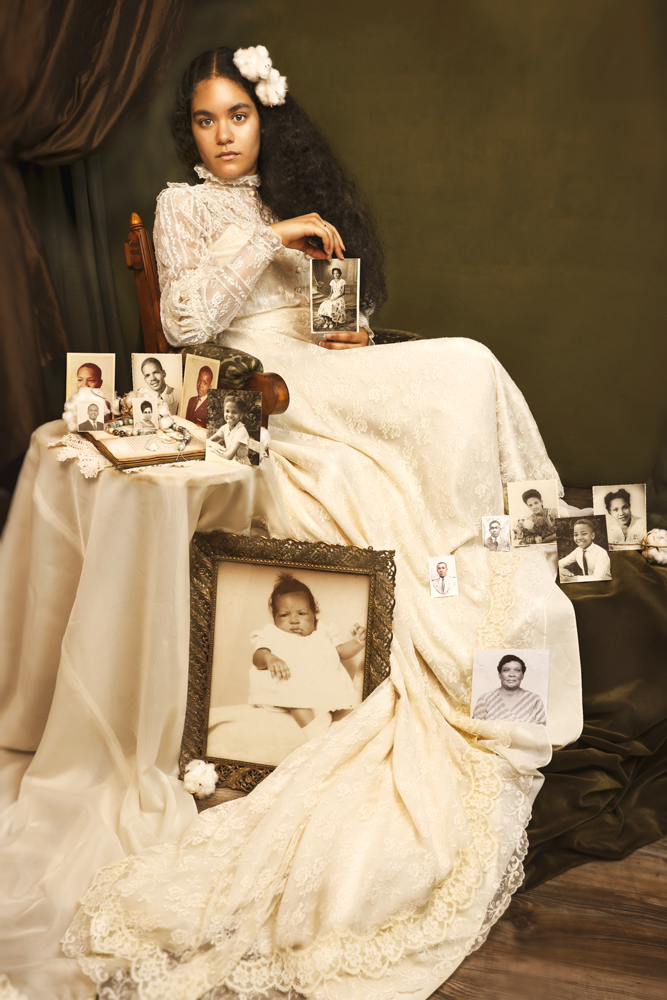

The “Reclamation” project explores the creolization of African American and European cultures. Photography, cyanotype, and embroidered/mixed media works will be created as storytelling elements, with subjects existing in an alternate and imagined physio-spiritual reality. The project serves to reconstitute spirit objects and cultural connections that never truly disappeared, but have been borrowed and subverted in plain sight throughout our life and ritual practices. These same symbols act psychologically to shift the embedded common narrative of the viewer of Blackness away from race and subjugation, and towards an expanded perception; a visual elevation of the subjects as powerful and holy in their own humanity.

The history of the photograph as it relates to Black bodies has evolved from depicting images of property, to one where we create and share iconography that speaks to shared cultural triumphs and tragedies. “The humblest servant girl may now possess a picture of herself which was once the special and exclusive luxury of the rich and great”–Fredrick Douglass. The photograph, commonly used as a weapon for propaganda, can also be used to heal and bind the wounds of those who are on the opposite side of the lens. There is power to be wielded in how a person sees him/herself and how they elect to project images of themselves and their people.

Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman said, “We cannot just have a vision of justice. We must be able to envision ourselves in that vision for justice to be served. For the right to representation that we all deserve.” These words lift my soul and speak directly to my core beliefs as an artist/photographer. My art is a ‘mirror-world’ used to capture and reflect back the soul of my culture within the larger society where we exist but are very often not seen. It is critical that both my audience and the subjects depicted in my ‘mirror’ to see themselves, in some way, reflected back. The viewer must know and own their own power, with full rights, worth and voice. Photography is a weapon and, in this way, is an advocate. Advocacy means challenging the viewer to address the political and social plight in the culture and society they live in. It also speaks quietly when necessary, weaving its way as a visual idea through, underneath and around the physiological and sometimes immoral fabric of a culture. Photography is an art that by definition captures and shifts perceptions. It is this kind of advocacy that I do within my work.

Perception of self and belonging begins in childhood. Children are the subjects I use to speak to ‘belonging.’ These Black and brown children revisit history, to re-examine history and tradition. It is my objective that children and adults view and imagine themselves and their history within these images. My work is the beginning of conversations exploring these rituals and material artifacts as a means of channeling our history. The children in my works act as the conjurers. Their innocence and purity open a portal to the ancestors and invite a rewriting of their history. Each subject is transformed into the ancestors they should have been able to see.

I’m a daughter of the Diaspora and a child of the American South. I’m rooted in a place that has not taught its children any true history, beyond suffering, servitude and second-class citizenship. People of color, and particularly their children, do not see themselves mirrored or represented when they visit most cultural spaces. As a child I recall vividly not feeling any connection to the faces that peered back at me. They bore no resemblance to me. My work addresses a void in history and it is a void of ‘worth’ that was forced upon me. Along with promoting the formal beauty in Blackness, my work intends to ensure that my children and those that come after them will have positive, corrected images of themselves. My work stands so that they will never know that sense of not being of worth – of not belonging to history. While the canon of art has slowly shifted towards interest in ownership of images of Black bodies in general, there is still a gaping hole of human understanding that I feel this project can begin to fill.

Daniel George: Along with photography, you are fascinated by ethnography, identity, and representation. What interests you about these themes, and how did that lead to the development of this particular project?

Tokie Rome-Taylor: Material, spiritual, and familial culture of descents of southern slaves are entry points for me. I use these themes to build symbolic elements that communicate a visual language and exploration of history. The research centers on their material culture, spiritual practice, and traditions. These have all been used to create a visual language that speaks to our shared history. My focus on identity, representation, culture and ethnography coincides with me being a southern, African American woman from Georgia who grew up with a sense of being the “other”. Historically, African Americans have been made to feel like outsiders in this place we call America, particularly in the south. This “otherness” creates an experience in the world that D.E.B.Dubois would refer to as “the veil,” this feeling of always being apart from society (whether true or false). It’s a sense of being able to see all of the benefits and possibilities the world has to offer but being separated from it. As an artist, this “otherness” has led me on a journey to reach back in time to connect to my history, understand identity, and what it means to be seen or represented within a society. It is a journey that doesn’t have a clear roadmap or guides. This body of work focuses on African American children from the south as historical ancestors who have traded roles. Wiithin traditional western art, people of the African diaspora were either omitted or were portrayed as objects of status and wealth for wealthy patrons who commissioned the works. They were staged alongside other objects that the commoners could never attain. They were not valued as a people but as property. This body of work reexamines that history, creating images of an alternative past, where these children’s humanity, history, and worth as a people are seen and celebrated. My portraits of Black children represent a visual elevation that has been omitted from the canon of mainstream “western art history”. I look for connections–threads– to how materials, cultural elements, and history can be used to layer symbolism and narrative within the work. I am intrigued by exploring how to communicate using not only images created with the camera, but also with the subject the camera focuses on and the materials used to create the final piece.

On this journey, my direct familial history did not give me the answers I craved. My mother has never really talked about her family members. There are secrets there. A continuation of the southern tradition of being seen and not heard, of not asking. In my family, secrets and information live and die, existing only for the people that were there to see it. I have never had a relationship with my father, so there is also that void. My way of dealing has been to search for broader connections, more of an academic approach. I grew up a member of Big Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church but never felt a connection to any of the religious aspects. As an adult, I questioned the practices of the church and really looked more into spirituality to investigate how the African spiritual practices overlap those of Christian religion in the south. A lot of the things I was doing in my work were instinctive; exploring African cultural practices such as adornment, leaving offerings for ancestors or how objects/artifacts have symbolic meaning and use. Robert Ferris Thompson’s Flash in The Spirit is an influential book for me as it gave me an academic starting point for what I was searching for. The more I delved into reading, exploring the notion of creolization, conjuring, and material culture,which were my search terms within the academic Journal database Jstor, there is this sense that my work is being guided by the unseen. A comfortable calm, as if I am doing what my ancestors have asked of me. I’m a southern girl and one tradition we had is taking a bath in the tub–never a shower. The tub bath is a place to sit and soak in, to meditate. My learning is the tub bath right now. There is a lot of knowledge that I am still soaking up, meditating on, diving into. There is so much more for me to discover, but each bit constructs threads of connection for me that lead me home.

DG: Could you talk more about your use of the cyanotype, embroidery, and mixed media processes. Why was it important to incorporate these visual approaches as opposed to relying on straight photographs—bringing your subjects into an “alternate and imagined physical and spiritual reality?”

TRT: I compose the photograph to capture layering of person, textures, and objects to reflect the ideas I have. Sometimes a pure photograph is enough to communicate that idea. However, sometimes that idea I am trying to communicate requires more. The use of beading, embroidery, gold leafing, cyanotype and/or wax are all inspired by the materials used in creation and adornment of clothing within traditional West African culture. The work becomes less about the pure photograph and more about the concepts and ideas the artwork is asking the viewer to explore. Photography has always been both my method of creating raw material, and my method of creating frozen moments in imagined historical time. It is a way for me to communicate my thoughts and ideas, much like paint and brushes are used by a painter. I explore mediums and layering in order to grant myself freedom from the expectation of how a photograph should ultimately exist. For me, the photograph is not about capturing reality, but about creating it. I am creating an alternative and imagined realm for my children to exist within that is hopefully reflective of an idealized reality they will ultimately inherit in real life.

Sometimes the image tells me it’s “done” as a pure photograph. The photographs are further manipulated digitally. I use multiple layers, painting in light and shadow and color. Further manipulation may come in the form of archival images digitally collaged within the piece, using the image as a digital negative for cyanotype or as the base image for physical manipulation via embroidery, beading, gold leafing on vellum or encaustic.

DG: Can you elaborate on your choice to focus exclusively on young women in these photographs? You write that this work promotes “the formal beauty in Blackness” and it “intends to ensure that [your] children and those that come after them will have positive, corrected images of themselves.” Frederick Douglass, whom you also reference, was certainly aware of the photograph’s power to accomplish this. How do you feel that your photographs begin to fill that “gaping hole of human understanding?” And why is it significant at this particular point in history?

TRT: Museums are the repositories of what a society supposedly values and deems culturally relevant, and they are also spaces that have, for centuries, chosen to ignore the artwork of people of color. Works that did have people of color in them were depicted in a subservient manner. This is a demeaning narrative that children of color have had to battle subconsciously. I know I did as a child and as a young adult.

The work is not limited to young women, but specifically to African American children.

They are a key subject in my work because I feel that African American children have primarily been ignored as the center within the canon of the artworld. This focus stems from my belief that our understanding of our place and worth within a culture or society is formed in childhood. Images of African American children re-examine history and tradition, representing a visual elevation that had been omitted from mainstream “western art history”. It is my goal to instill a connection to history and tradition in the children as well as adults taking part in this project and those that view the artwork. Children need to see themselves depicted in a manner that celebrates them, their history, and heritage. Without this visibility, a subconscious sense of not belonging within a society is created within an individual. On the flip side of this, they get bombarded with negative stereotypes in the media that criminalize them or sexualize them at an early age. So on one hand there are museums and art spaces that are the repositories of what a society supposedly values and deems culturally relevant. Spaces that have for centuries, chosen to ignore the artwork of people of color. This absence of Black childrens’ presence in cultural spaces is combined with visual representation in the media that centers on negativity. This is a demeaning narrative that children of color have had to battle subconsciously. One the other hand… the work I create combats that. There is a subconscious learning that happens when we see ourselves portrayed in a certain manner. I want my subjects and those viewing them to make that connection to elevation, power, and worthiness to be seen. Beyond that I also want to make sure that these children and those viewing these works understand that as an artist, I am also a teacher, teaching what I feel our society should value, based on my experiences. It’s really important to explore visibility—who gets seen versus who isn’t worthy of being seen. My children, literally and figuratively, should be seen. They are seeing themselves as strong, unafraid–confrontational even, pure and open to the world. Children are my conduits to connect to elevation, spirituality, and ancestors, but they are also my way of speaking to who our society should deem worthy.

DG: You are currently working on a book for the Reclamation Project. Is there anything you’d like to share about its current development, and what else we can expect looking forward to its completion?

TRT: “Reclamation” is nearing a point that I feel proud to share with the public. It will be a self-published book and I have learned so much on this journey of creating it. One major takeaway is that creating a book is an entirely different learning curve than creating artwork! It seemed like a simple idea at the time; create a book of my artwork. However, it has grown into a project that encompasses a critique of the artwork, an archive of the sitters and their stories, and an opportunity to reflect on the symbolism I have created within the works. It really has acted as a tool to develop myself as an artist, which was an unexpected outcome. I have several wonderful curators and arts writers who are contributing essays to the book. Berrisford Boothe is an art, writer and Professor of Art at Lehigh University. He is the former curator and current advisor for Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art. Juana Williams is an arts curator and writer residing in Detroit, Michigan. Her curatorial practice predominantly focuses on deconstructing cultural and social issues, transgressing traditional boundaries of art criticism and curation, and countering anti-blackness within the arts. Williams has held multiple positions at various art institutions including the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. These two individuals consider the works through the lens of art and history. Additionally, several of the sitters’ families, all from Georgia, have included their narratives and archival images of family photos and artifacts. It was really important to me to include both the essays and the narratives of the families that were involved with the creation of the artwork. So much of African American history resides in an oral narrative that stories have the potential to get lost if the griot of the family passes away before the stories are passed down. The families and I had long conversations about family heirlooms and passed down legacy items. A common thread in the conversations was that on the surface, the families did not think they had any family mementos or artifacts. Many shared that the strife of poverty, migration from one area of the country to another, or the focus on simply living, left little thought to passing down family history or identifying family heirlooms. The conversations were revelatory to them and sparked family conversations with elders that ultimately identified family heirlooms and history that may have been lost or forgotten if not for the project. I felt honored to weave together their family heirlooms and stories with my artistic practice.

The monograph is currently available for pre-order and will be out in 2022.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026