Evan Hume: Viewing Distance

For the past few days, we have been looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Evan Hume and I discuss Viewing Distance.

Evan Hume is an artist and educator based in Ames, Iowa where he is Assistant Professor of Photography at Iowa State University. He earned his BFA from Virginia Commonwealth University and MFA from George Washington University. Raised in the Washington, DC area, Hume’s approach to photography is informed by the experience of living in the nation’s political center for much of his life and focuses on the medium’s use as an instrument of the military-industrial complex. He has exhibited widely at venues including Fotografiska (New York, NY), Filter Photo (Chicago, IL), Office Space (Salt Lake City, UT), and Furthermore (Washington, DC). Hume’s work has been featured by publications such as Aperture and Der Greif and is included in the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s Midwest Photographers Project. His first monograph, Viewing Distance, was published by Daylight books in 2021.

Viewing Distance

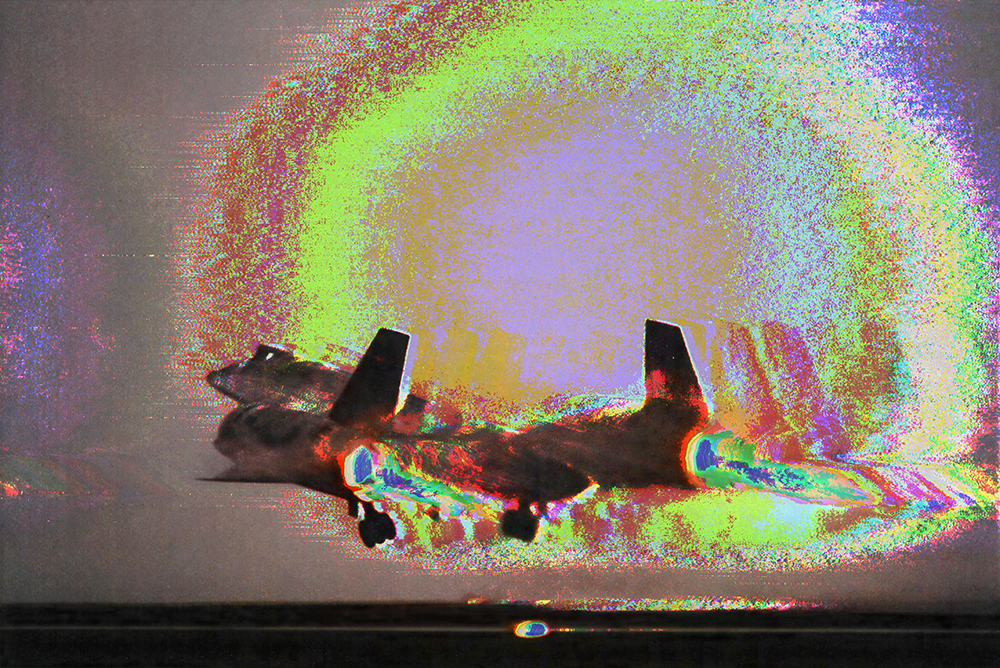

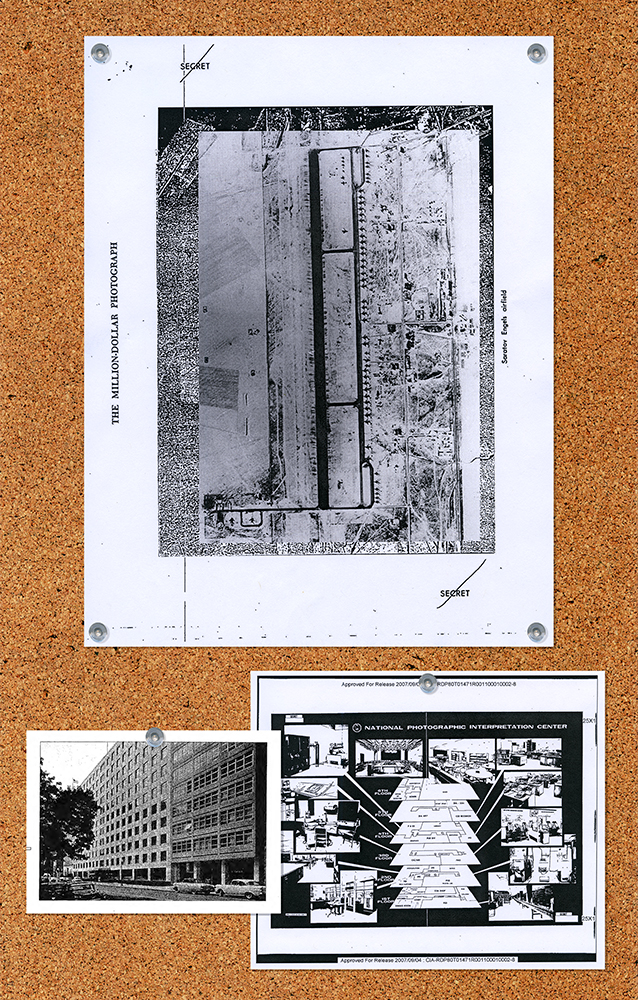

Photography’s technical and operational development in the twentieth century and into the twenty-first is inseparable from political conflict. This is the focus of my series, Viewing Distance, which grew out of many years of researching photography’s use as a tool of the military-industrial complex for surveillance, reconnaissance, and documentation of advanced technologies. I obtained the source material for this work by searching through the National Archives and filing Freedom of Information Act requests to intelligence agencies. The resulting body of work highlights interstices in the history of photography as well as the relationship between photography and the expansion of the US national security state.

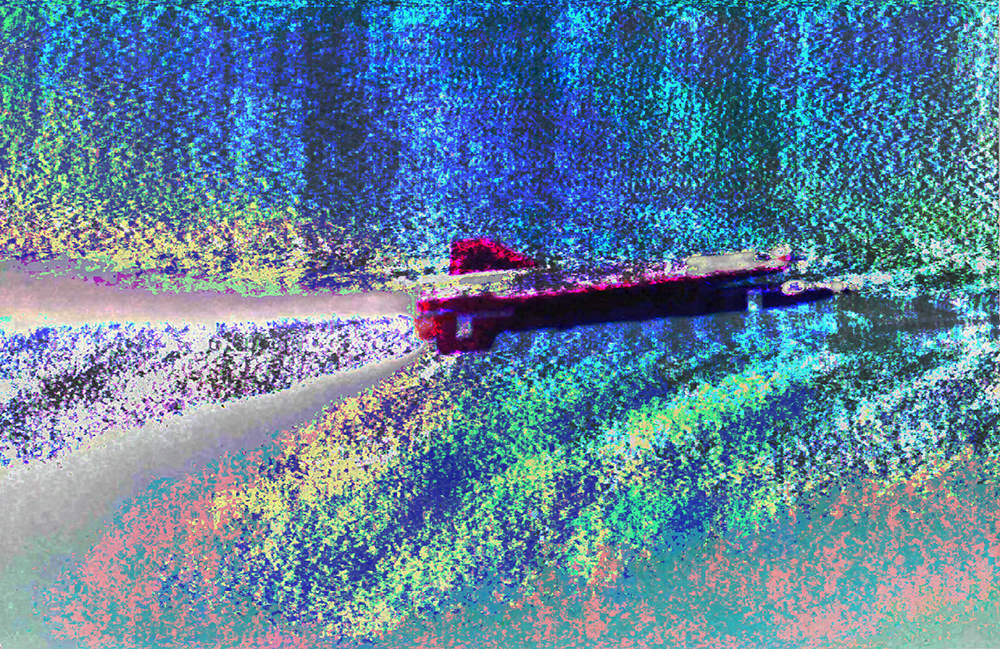

The emergence of Soviet nuclear capabilities in 1949 was a cause of great alarm in the US, and the so-called bomber gap—the unfounded notion that the USSR had surpassed the US in its arsenal of bomber jets—was used to justify increased defense spending and the buildup of a bomber fleet by the US Air Force. By the early 1950s, President Eisenhower and national security officials believed that innovations in aerial photoreconnaissance were necessary to assess Soviet weapons capabilities. Aerial photography’s goal during the Cold War became capturing images of Warsaw Pact military installations while avoiding detection by Soviet radar systems. The results of this photographic desire were significant developments in camera systems as well as high-altitude and high-speed aircraft created from a partnership between government agencies, corporations, and academia. This expansion of photographic operations was the precursor to the satellite and drone imaging that have become essential to intelligence gathering and preservation of US global dominance.

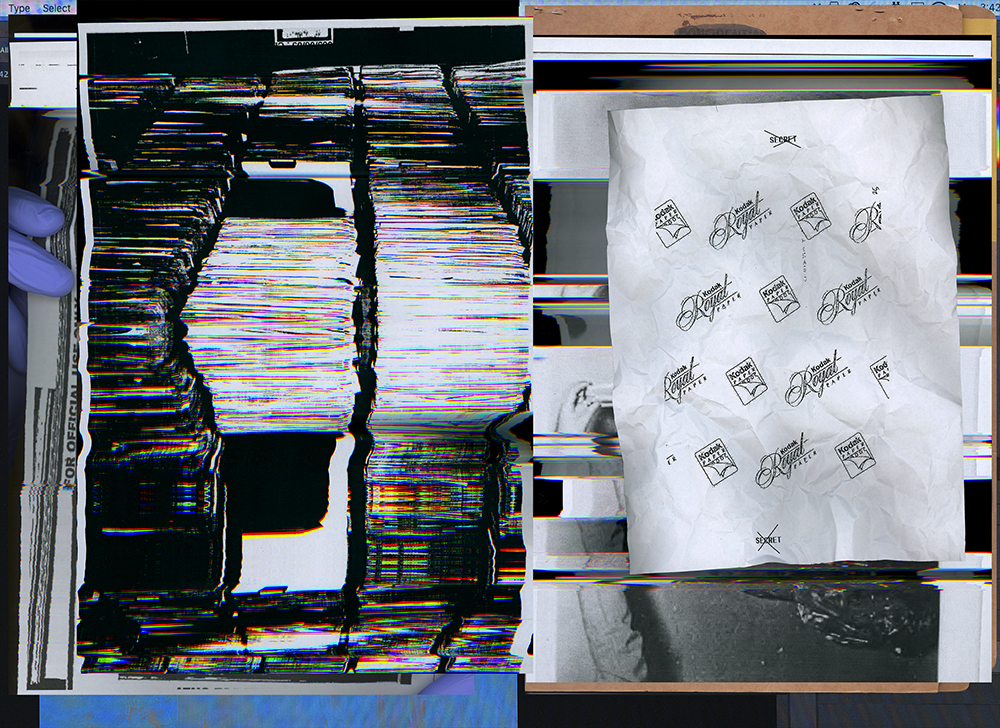

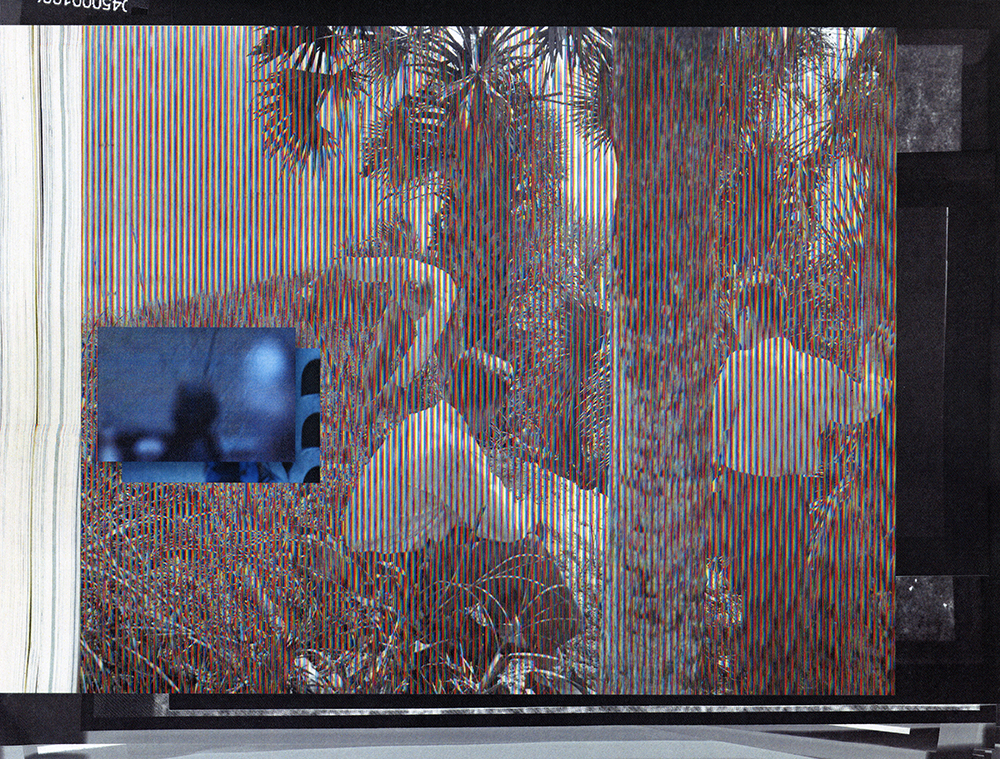

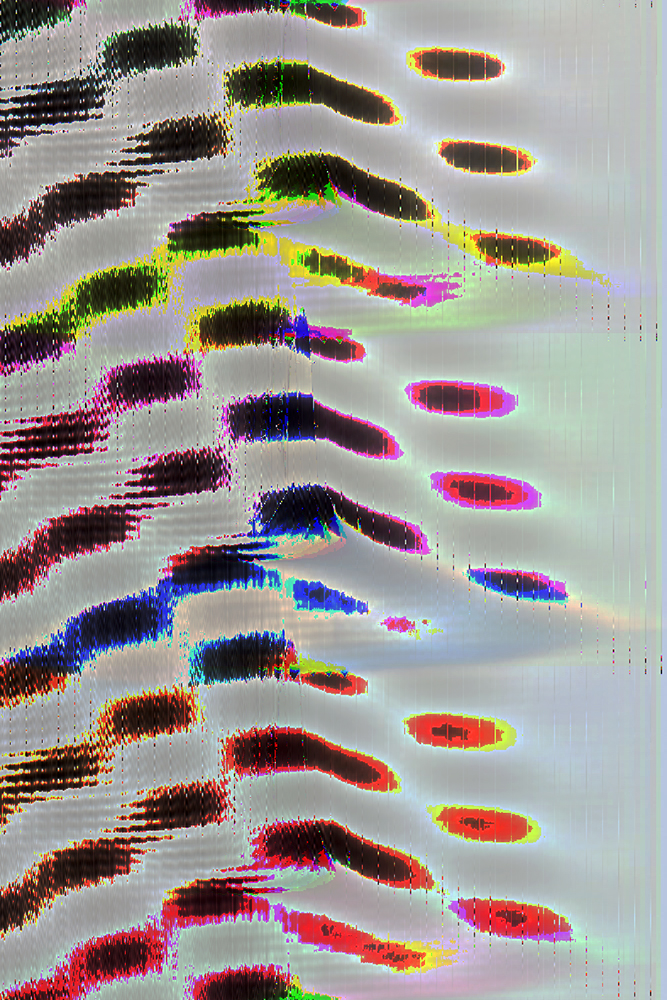

The source images that make up the pictures in Viewing Distance provide a distorted and fragmented archival glimpse of photography in the service of US imperium. While many of the images date back to the mid-twentieth century, they have only recently been declassified and much information remains secret. These pictures represent the decades-long time delay from when knowledge comes into being and when it becomes publicly accessible. Viewing Distance combines photographs pertaining to Cold War developments in photographic technologies with contemporary documents and devices, connecting past and present with implications for the future. Processes including analog printing, digital collage, scanner manipulation, and data bending are used to animate the archival material as well as emphasize the tension between informational and enigmatic source images. Through this disruption and layering, historical fragments are presented in a state of flux, open to alternate associations and implications. What we are allowed to know and see is often incomplete and indeterminate, encouraging speculation and critical vision.

Daniel George: I’d like to hear about how this project began. What got you interested in the government archives and how photography is used within the military-industrial complex?

Evan Hume: It’s been many years in the making. My family moved from New York to the Washington, DC area when I was 14, and I ended up spending a large part of my life in that region. The federal government has a huge presence in the local culture, so that was the world I grew up in. The September 11th attacks happened just a couple of weeks after I started high school and being in one of the areas directly impacted was eye opening. I’ll always remember the sound of fighter jets patrolling the skies that day. The immediate post-9/11 era and “war on terror” were transformative for me in how I saw my surroundings and the world at large. It was a personal political awakening, and like many people at the time, I felt the Iraq War was unjustified. I wanted to understand how and why this was happening and what the world-historical implications were. Over time, it became clear to me that the key to understanding much of this was to understand the operations of the military-industrial complex and intelligence apparatus as they relate to the US’s objectives for maintaining extra-regional hegemony.

Those concerns and perspectives took a while to manifest explicitly in my work. My first breakthrough in that regard was in grad school when I began working with archival photographs, which I was led to in a sort of funny way. In college and grad school I would listen to a late-night radio show, Coast to Coast AM, which covers all things paranormal and conspiratorial. I became particularly fascinated with UFO culture and the mythology surrounding it – alleged extraterrestrial encounters, government cover-ups, etc. I even attended a UFO conference at the National Press Club while in grad school, which got me thinking about UFO photography. I met a man who claimed to be photographing UFOs above Capitol Hill at night. The images were noisy and unintelligible. I was very interested in abstraction at the time, and it occurred to me that alleged UFO photographs often had an abstract quality. I knew from my interest in the UFO phenomenon that the government had conducted investigations of UFO reports from the late 40s to the late 60s under the Air Force’s Project Blue Book, so I decided to see if there were photographs from those files that I could access. It turned out they were available from the National Archives, so I ordered rolls of microfilm containing photographs from the Blue Book case files. I found that many of the photographs were very abstract – high contrast with minimal details. They looked more like photocopied modernist paintings or collages rather than photographic evidence. That was the start of me working with archival images that functioned as indeterminate historical fragments. From there, I began thinking more broadly about how photography has been used by the military and intelligence agencies, which is the basis of my book, Viewing Distance.

DG: What does your research process look like? Would you mind sharing your methodology?

EH: I have a few methods for how I obtain the material I work with. As I mentioned, I began by researching the National Archives and I continue to do so. They have many records that are available as digital files, and you can also order reproductions as I did with the Blue Book photographs. Most government agencies have released select declassified files that can be downloaded directly from their websites. If I’m looking for something that hasn’t been released, I file a Freedom of Information Act request.

I filed my first FOIA request while in grad school. I was researching the CIA’s involvement with American modern art in the mid-twentieth century. As historians such as Frances Stonor Saunders have written about, the CIA was covertly funding exhibitions of American abstract art to frame the US as a champion of free expression in contrast to the socialist realism of the USSR. I requested documents pertaining to modern art as well as the contents of the CIA’s art collection. It took 10 years for the request to be fulfilled. I received a list of works in the art collection, but most of the pictures were redacted. The other documents provided were essays written about modernist abstraction to accompany exhibitions of artworks at CIA headquarters.

For Viewing Distance, I was focused on researching a significant moment in photography’s technical and operational development – the creation of high-altitude, high-speed photoreconnaissance aircraft and the advent of satellite imaging during the first decades of the Cold War. There is a direct connection between major advancements in photographic capabilities and the expansion of the national security state. I obtained files mostly from the Air Force, CIA, National Archives, and National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). I was able to find CIA and NRO documents outlining the histories of photoreconnaissance planes and satellites that were originally classified and only intended for those with clearance. The documents were helpful in gaining an understanding of technical information and specifics about the development of certain government projects although they contain redactions, so secrets remain. I also read critical texts that give geopolitical context to the material I work with, such as Perry Anderson’s American Foreign Policy and Its Thinkers.

DG: Based on what we can view on your website, you often incorporate found imagery in your work. What role do you feel this plays in your creative practice?

EH: My encounter with the Project Blue Book files led to an interest in photographs that are rooted in specific historical circumstances but have some degree of obfuscation due to reproduction, redaction, or how the image was originally captured. These sorts of photographs go against common expectations of photographic evidence (clarity, detail) and call attention to a shared condition of all photographs as fragments that only every show part of a larger “picture.”

Photographs transform as they circulate both in bureaucratic archives and in the public sphere. They shift contexts, they are photocopied, scanned, compressed, and resized while losing and gaining information along the way. The overlapping processes of circulation and transformation can expose the fragility and malleability of photographic images as well as the fragility and malleability of historical narratives.

DG: I was drawn to the visual quality of your photographs—particularly the use of digital manipulation to distort information. Could you talk more about this process as it relates to highlighting “tension between informational and enigmatic source images?”

EH: This is related to what I mentioned about working with photographs that have varying degrees of obfuscation. Some contain representational and intelligible elements (despite marks and distortions from reproduction) while others are veiled by redaction or repeated photocopying. Sometimes this dichotomy will exist within the pages of the same document. For Viewing Distance, my approach to digital editing and collage was influenced by the differing states in which I encounter archival photographs coexisting. I also think of my digital collage processes as ways to visualize the layers of time within archives as well as the physical and digital forms the images can simultaneously inhabit. I see Viewing Distance as a montage of images in states of transition, as they circulate from the archive out to the world, entering new relations with other images and shifting from print to digital file and back again.

DG: I am fascinated by the idea of information being declassified by the same entity that maintains secrecy around other related facts or details—making clear that we are only allowed mediated pieces of an entire picture. I cannot help but draw parallels with the positionality of a photographer and the ways in which a photograph operates in an identical manner. Would you elaborate on how your work encourages “speculation and critical vision” as it relates to what “we are allowed to know and see?”

EH: An important realization I had when I began working with archival photographs is that photography can conceal just as much as it can reveal. As viewers, we only see what the photographer and camera allow us to see, and a photograph can possess both specificity and ambiguity. A common tendency when looking at a photograph is to want to understand it: what’s happening? What’s the story behind it? I think all photography encourages speculation to an extent. From the denotative elements of the photograph, connotations and associations arise.

The presence of redaction and visual references to image-making and editing in my work (e.g., a developing tray, Photoshop tools, scanner marks, artificial shadows) invites criticality and questioning. I like the way art historian Lily Brewer describes an aspect of my work in her contribution to Viewing Distance, that I’m attempting to “stop the flow” of declassified photographs momentarily and highlight their indeterminate, fragmentary nature through digital intervention. I want to present the photographs as precarious pictures with ideological origins rather than neutral, transparent historical documents.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Scott Offen: GraceDecember 12th, 2025

-

Izabella Demavlys: Without A Face | Richards Family PrizeDecember 11th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 2November 27th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 3November 27th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 4November 27th, 2025