Joel Jimenez: Castle of Innocence

For the next few days, we are looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Joel Jimenez and I discuss Castle of Innocence.

Joel Jimenez is a visual artist, cinematographer, and independent curator who lives and works between Costa Rica and Spain.

His research-driven work explores themes associated with environmental psychology, place-identity, and the role of memory in our conception of history, perception of reality, and understanding of time.

His projects are interested in the in-between states, the emotional climate that emerges from stagnant conditions, and the atmospheric experience of silence, solitude, and nostalgia.

Joel’s work is shown internationally in group and solo exhibitions including PhotoEspaña, Singapore International Photo Festival, and Photo Israel. He was selected as a LensCulture Emerging Talent, Fresh Eyes talent, nominated twice for Prix Levallois, and a participant in portfolio reviews like Emergentes in Encontros da Imagem. His projects have been featured extensively in printed and online publications such as the British Journal of Photography, GUP Magazine, LensCulture, PHmuseum, Der Greif, Revista Balam, among others.

Castle of Innocence

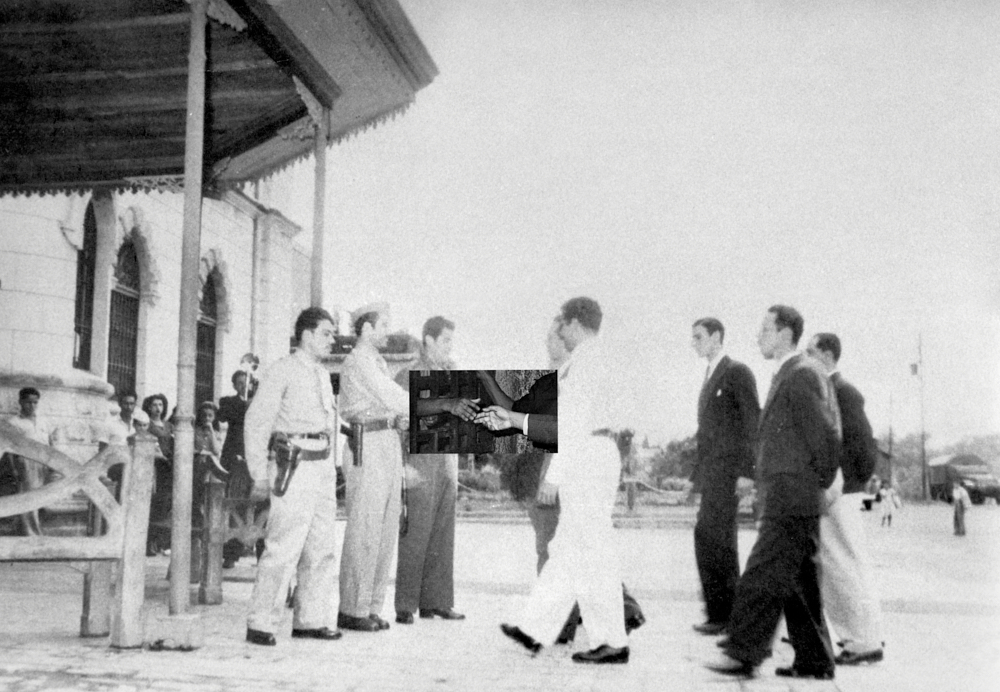

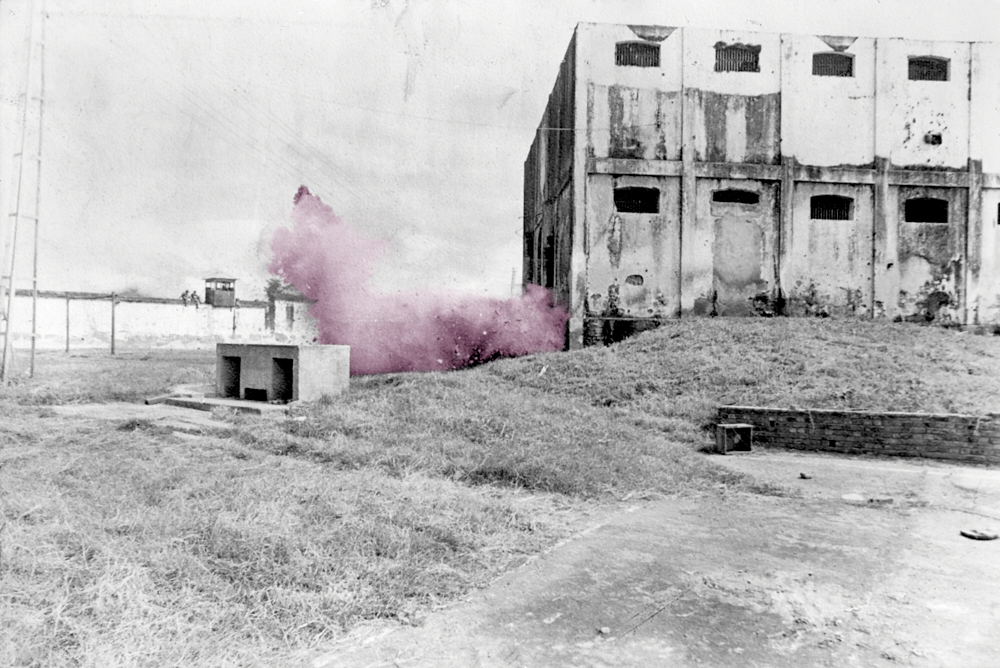

Castle of Innocence delves into the building of the Children’s Museum of Costa Rica – an imaginative museum space dedicated to children’s education through interactive and colorful scenarios – and its cultural heritage as the country’s former central prison.

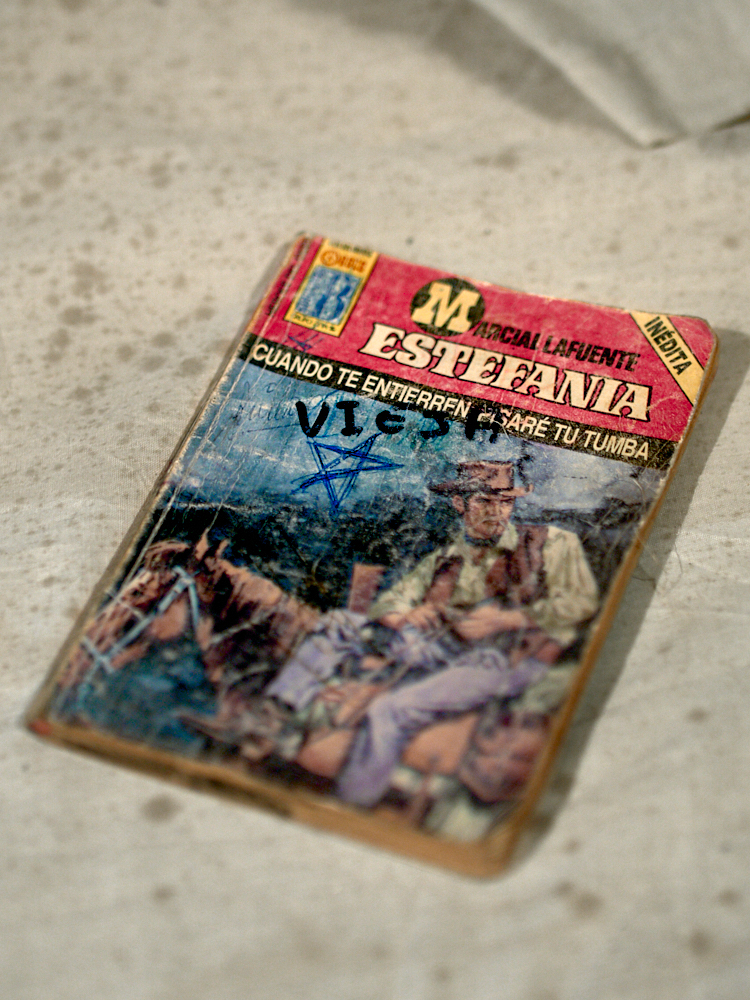

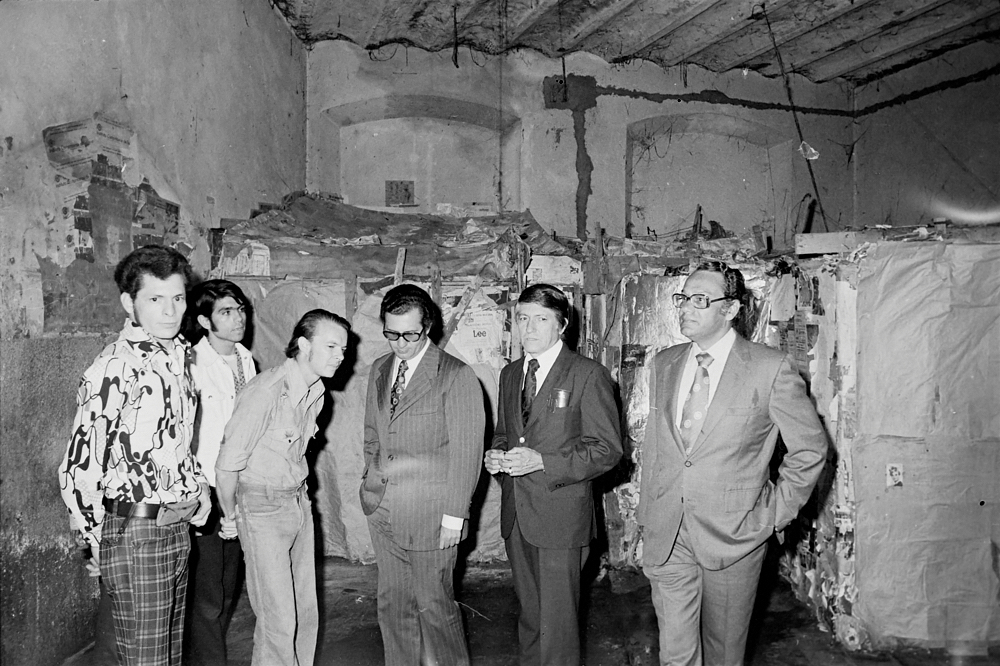

By working with archive material from the prison era and different environments and objects from the museum, the project questions the role of power structures in the construction of historical narratives, and the use of photography as a document of truth.

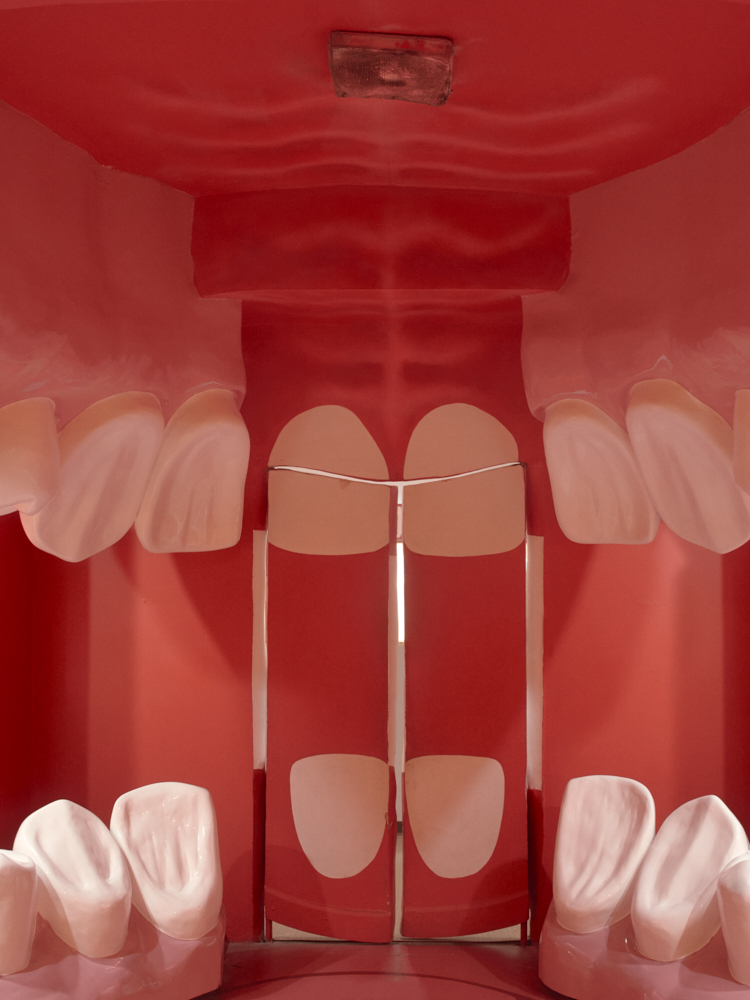

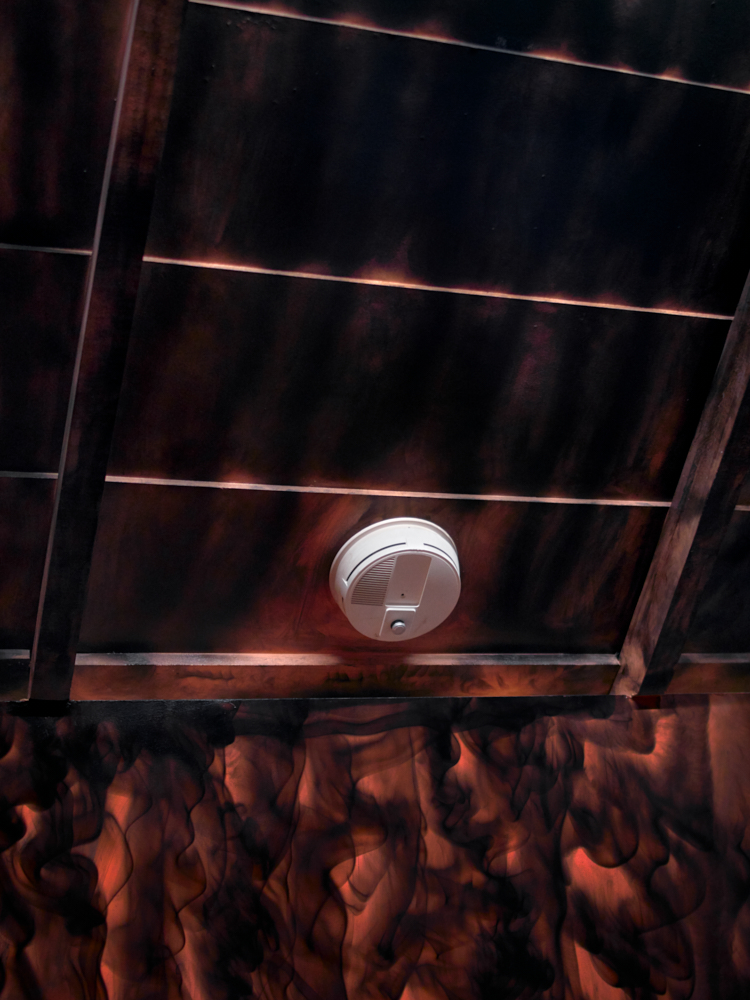

Both the prison and museum are institutions designed to contain physical or symbolic representations of collective identities. In this regard, the project merges both spaces in a nonlinear narrative to confront the imprints of trauma and violence from the building’s past as a prison with the illusory atmospheres in the museum’s current context.

Because of the secrecy and ominous nature of the prison, there are a lot of gaps and absent information, therefore, in its retelling, many stories carry both factual details and myths, provoking the boundaries between reality and fiction to start to dissolve.

In the same way, the children’s museum uses storytelling devices and imagination to educate on different themes including historical events such as the prison’s past through replicas of prison cells from various periods.

These parallelisms allow for a reflection on the multiple tensions, reoccurrences, and contradictions that concern the dissemination of knowledge, history, and collective memory, whereas it also provides ground to examine the liminal space between protection and control in our current post-truth era.

Daniel George: Tell us more how this project came about. What brought the Children’s Museum of Costa Rica and its history to your attention?

Joel Jimenez: A few years ago, my brother told me to go with him and my niece to a place called the Children’s Museum. I vaguely remember that I visited the place when I was a child on a school trip.

Going into the museum, I found a place that seemed paralyzed in time. Most of the spaces and objects seemed dated. The building kept the same architecture as its original function as a prison, reminiscent of a panopticon.

Wandering through this maze, I could see that the atmosphere carried the heavy weight of time within. But what was fascinating was the fact that the museum had just opened a section dedicated to its past as a prison. In that section they constructed replicas of prison cells to mimic what could’ve been life at the prison.

The idea of illusion and imagination combined with the historical trauma of the building got me motivated to start the research process of this project and begin learning about the history of the place to see what lied beneath the surface of those walls.

DG: I’m curious about your general approach to your creative work, and from where these interests derive. What do you find compelling about “the emotional climate that emerges from stagnant conditions, and the atmospheric experience of silence, solitude, and nostalgia?”

JJ: I conceive the photographic practice as an interlocutor medium between the internal and external world. The image works as a space for projection, representation, and reflection of these oscillations between the two worlds.

The internal world that I mention is made up of personal mythology that is traversed by my life experience. Different elements, motives, and emotional states recur in my production as echoes of a process that, like memory, is transformed every time it is invoked.

In this personal mythology, I find an obsessive search to represent intermediate states, generally associated with stagnation, pause, and waiting. An exploration of atmospheres linked to oblivion, absence, and silence also converges in this universe; I try to understand how to dialogue with the affections that cross my sensory experience in relation to the environments that surround me, and with this, I generate an approach to individual and collective memory.

I study the mechanisms that configure our reality based on mnemonic elements, traces, and clues that function as questions and reveal the malleability of our experiences that configure our identities.

I would like to think about my photographic approach as a mix between different research methodologies and fields of study (history, psychology, sociology) and a meditative process in which I dive into the affects and sensorial qualities of a space. Both rational and emotional intersect to work on the atmospheres of the environments in which I find connections with my own identity.

DG: Could you talk more about your process and incorporation of archive materials in your images? Why do you feel that this approach is best suited to question photography’s role in both memory and history?

JJ: An objective throughout this project was to work with the contradictions that lie within the building. Documentary meets with imagination to understand both the prison reality and the children’s museum illusionary environment.

In that sense I began to think of ways to talk about history in a nonlinear method. I found Aby Warburg’s Atlas Mnemosyne as a strategy to puzzle the multiple timelines of the building together according to different themes or ideas that were discovered during the investigation.

Through this methodology, I discovered that I could combine multiple materials and strategize the reading of it through themes or ideas that could be traced to the reality of the museum/prison space.

In my opinion, even though this practice can be overwhelming, it allows for multiple layers to come through and reveal new interpretations in the intersections of the different information that is presented.

DG: You write that through various creative strategies, “boundaries between reality and fiction start to dissolve, and a renewed sense of place-identity surfaces.” In what ways do your photographs accomplish this?

JJ: Photography has a very complicated relationship with truth. Its inevitable referential condition (although questionable) will provide a connection with some kind of truth. As a tool it is subject to control and power structures that determine its conditions, parameters, and restrictions.

I believe that photography allows for a circulation of truths (individual or collective) that should be placed in tension and interaction. In that dialogue there should be both a rational and an emotional discussion about the contradictions that arise in their connections.

I also believe in the power of memory as a device for truth. Reality does not always equal to veracity, and in many cases I see validity in the capacity of emotional reasoning and imagination to understand someone’s truth or identity.

Both museum and prison are seen as structures of institutional power, with that mindset I wanted to reflect on the thin line between control and protection. History as a narrative tool is always determined by context and subject. Whoever determines a dominant narrative can fade the traces of all the other stories that contradict or darken that history.

Photography works in similar ways, particularly in its interpretation as a lens to access certain realities. Construction, intervention, and selection are all processes that are intertwined with image devices and (his)storytelling.

In that way I wanted to talk about these issues from a standpoint more related to memory, in which that speculative intention is inherited and where fact and fiction can be used together to generate an emotional reality.

DG: One component of this project that I found intriguing was the inherent unease of the museum’s history and current role within the community. Of all the potential approaches to this series, why did you feel it was important that images maintain an “ominous atmosphere?”

JJ: I perceive the project as a labyrinth in which the viewer chooses how far they want to go into the multiple layers it presents. In that sense, I always imagine the viewer of the work as someone that enters for the first time in the real Children’s Museum of Costa Rica.

This experience is very interesting because at a first glance you receive the layer of color and games that the museum presents, but as you travel through it you start to see the broken instruments, the cracks through the walls, and then you understand its past as a prison, the violence, the darkness.

I see the project as a space of observation and examination; in that sense, each viewer will get something different from each viewing. What I do hope is that the atmosphere of the space carries without regard to the meaning to the spectator.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026