Paloma Lounice: Ramona

This week we are looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Paloma Lounice and I discuss Ramona.

Mexican and American photographer Paloma Lounice explores intimate themes in her work such as family heritage, identity, and memory as constructs. With a degree in Modern Languages and Intercultural Studies, most of her photographic training was through Centro Fotográfico Manuel Álvarez Bravo in Oaxaca, Mexico. Her project Ramona was selected for a solo exhibition at the same institution, and her work has been shown in various collective exhibitions and publications in Mexico and the United States.

Follow Paloma Lounice on Instagram: @palounice

Ramona

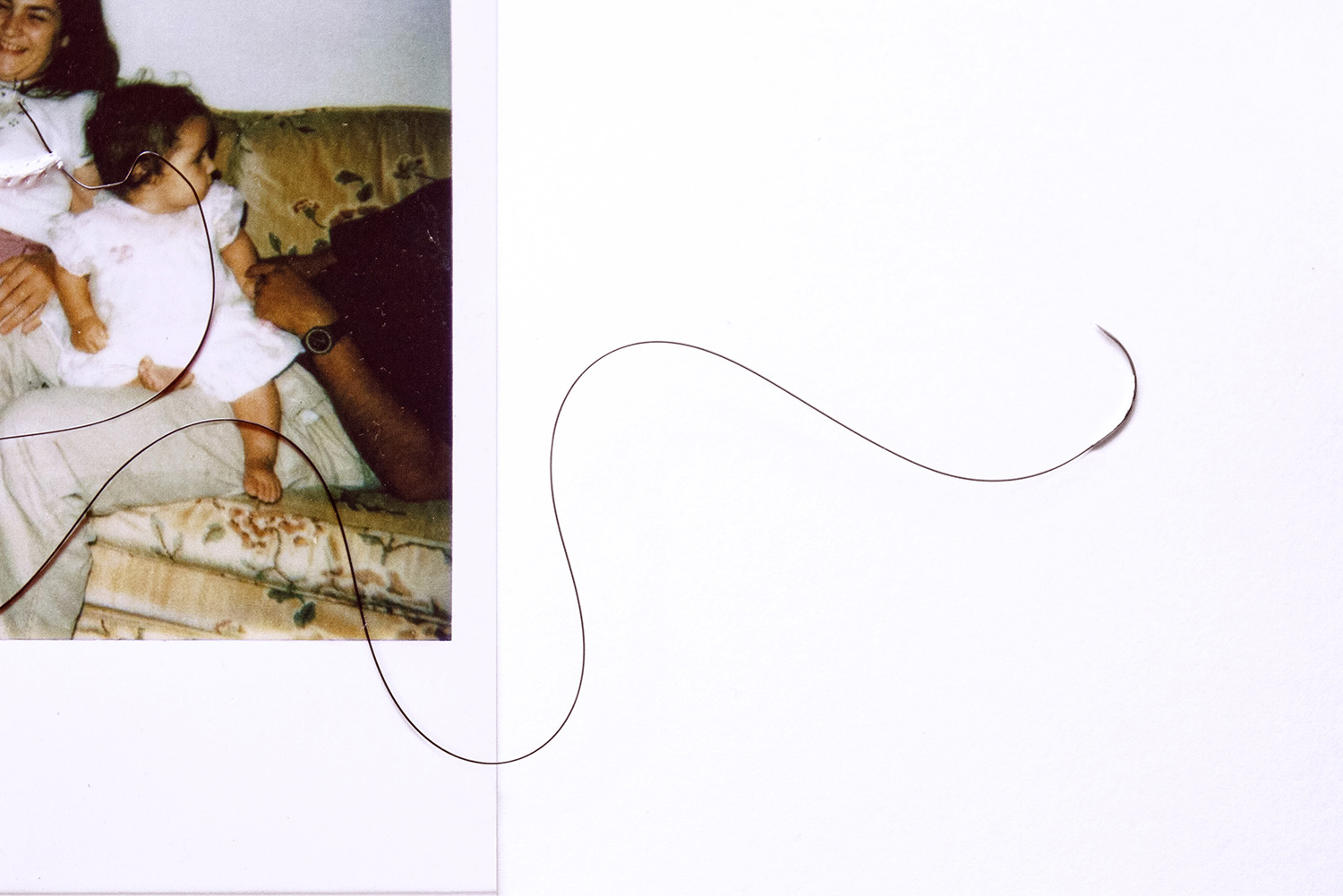

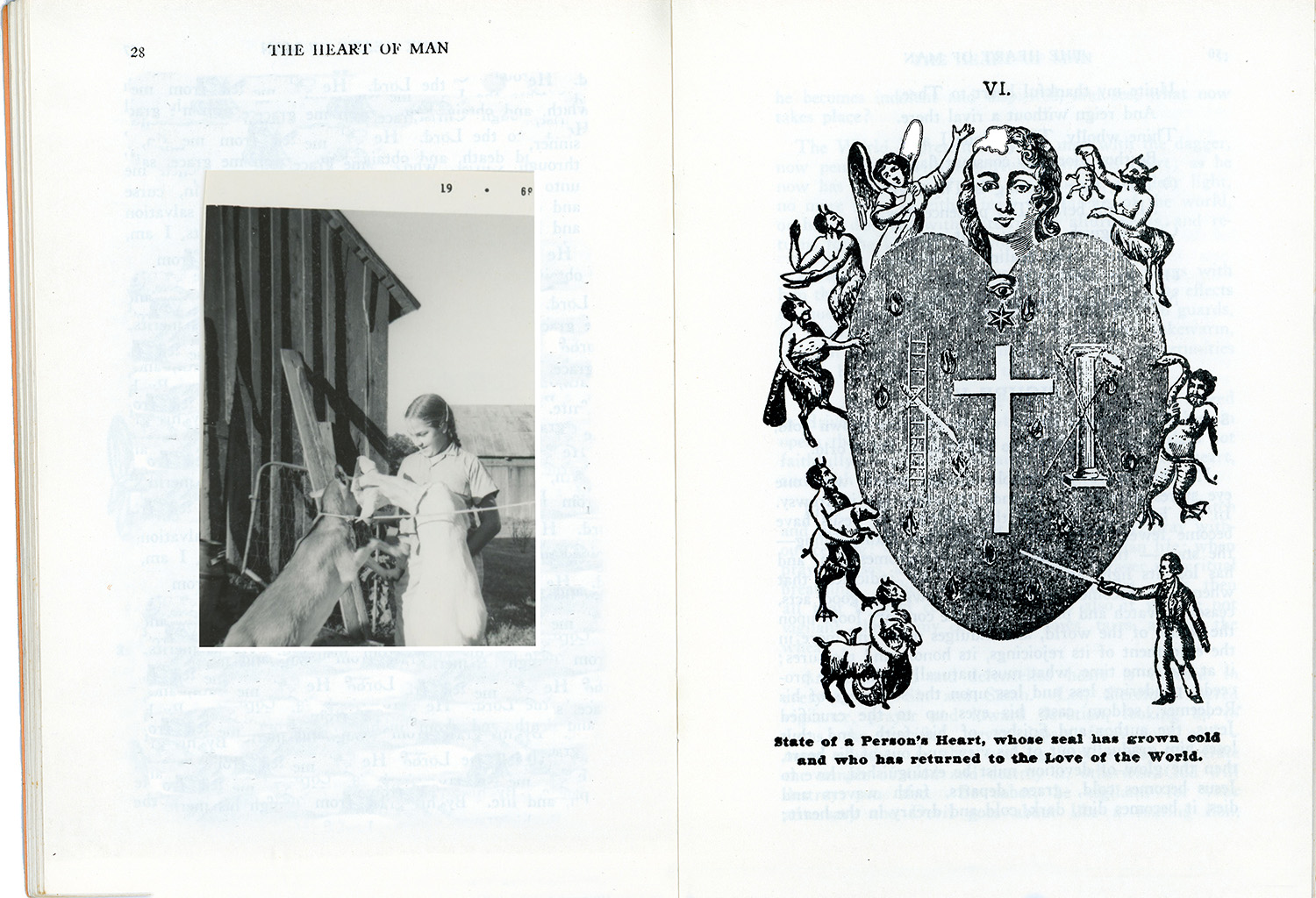

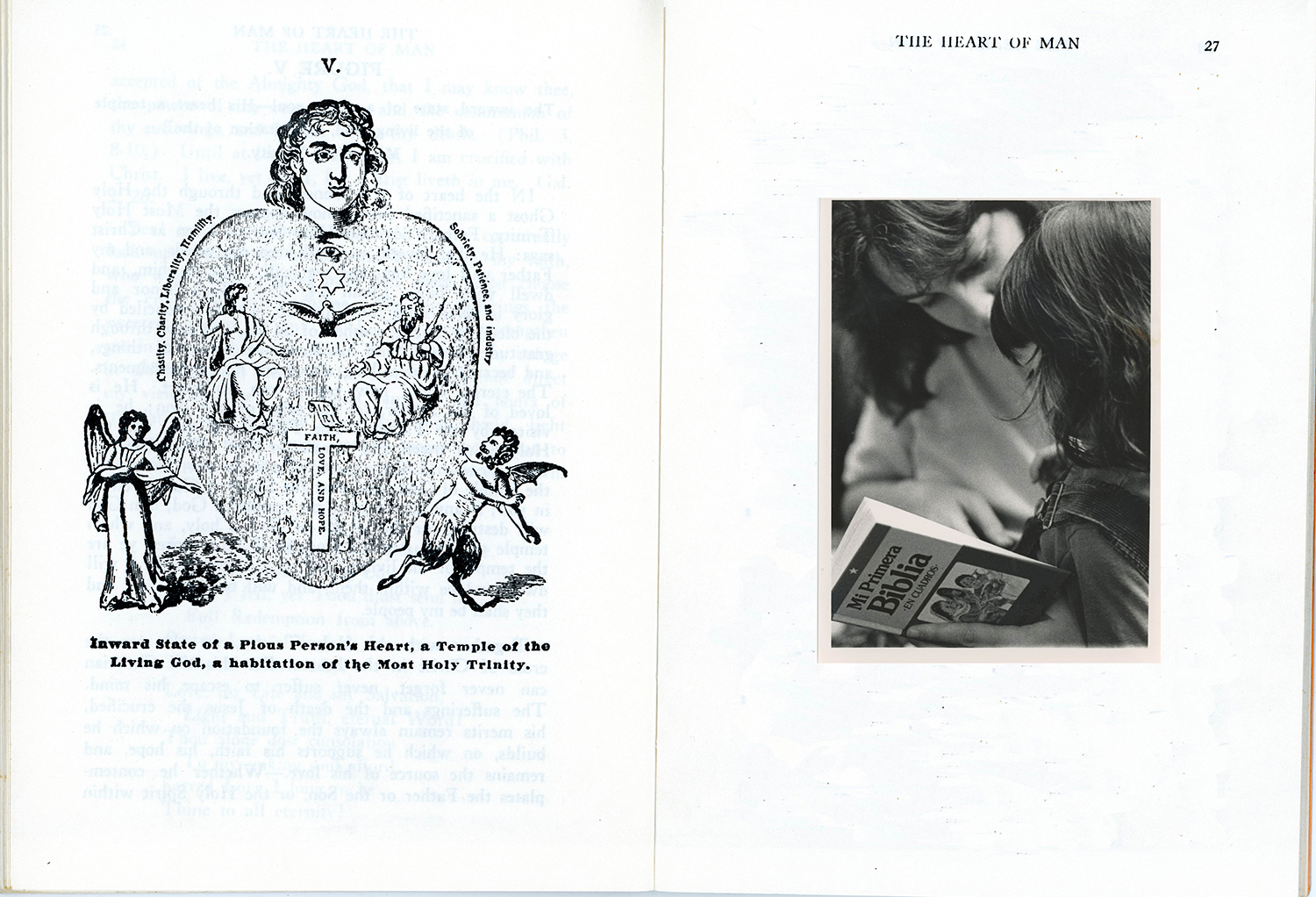

Ramona is the first chapter of an ongoing series that explores intergenerational heritage, memory, and identity as constructs. Serving as a line of conversation between mother and daughter, Ramona explores the continuity and noncontinuity of family narrative through archival images and photographs of my own. I take ownership of my family albums and heirlooms to deconstruct and retell their story. By tracing a dialogue with my mother in this way, I give her absence a place to be.

Daniel George: How did this series begin, and what prompted your interest in creating a body of work that functions as a portrait of your mother?

Paloma Lounice: I began Ramona unknowingly when I started photographing objects (quarantine was brutal) that I kept in my personal treasure box. I realized that everything I photographed was a keepsake of my mother. I started digging through the mountain of old photographs, tapes, transparencies, documents, negatives, and other archival material in my family’s possession. My mother passed away when I was 11 and I felt a need to reconnect with her. This work grew out of my need to get to know my mother and say “this is me”, “this was you”, and “this is each of us in each other”.

DG: This work is unique to other projects that we can see on your website, as it is the only that utilizes archival photographs. I am really fascinated by the dialogue that you create between these, and photographs you have made yourself. In what way do these images collectively produce the family narrative that you wish to share?

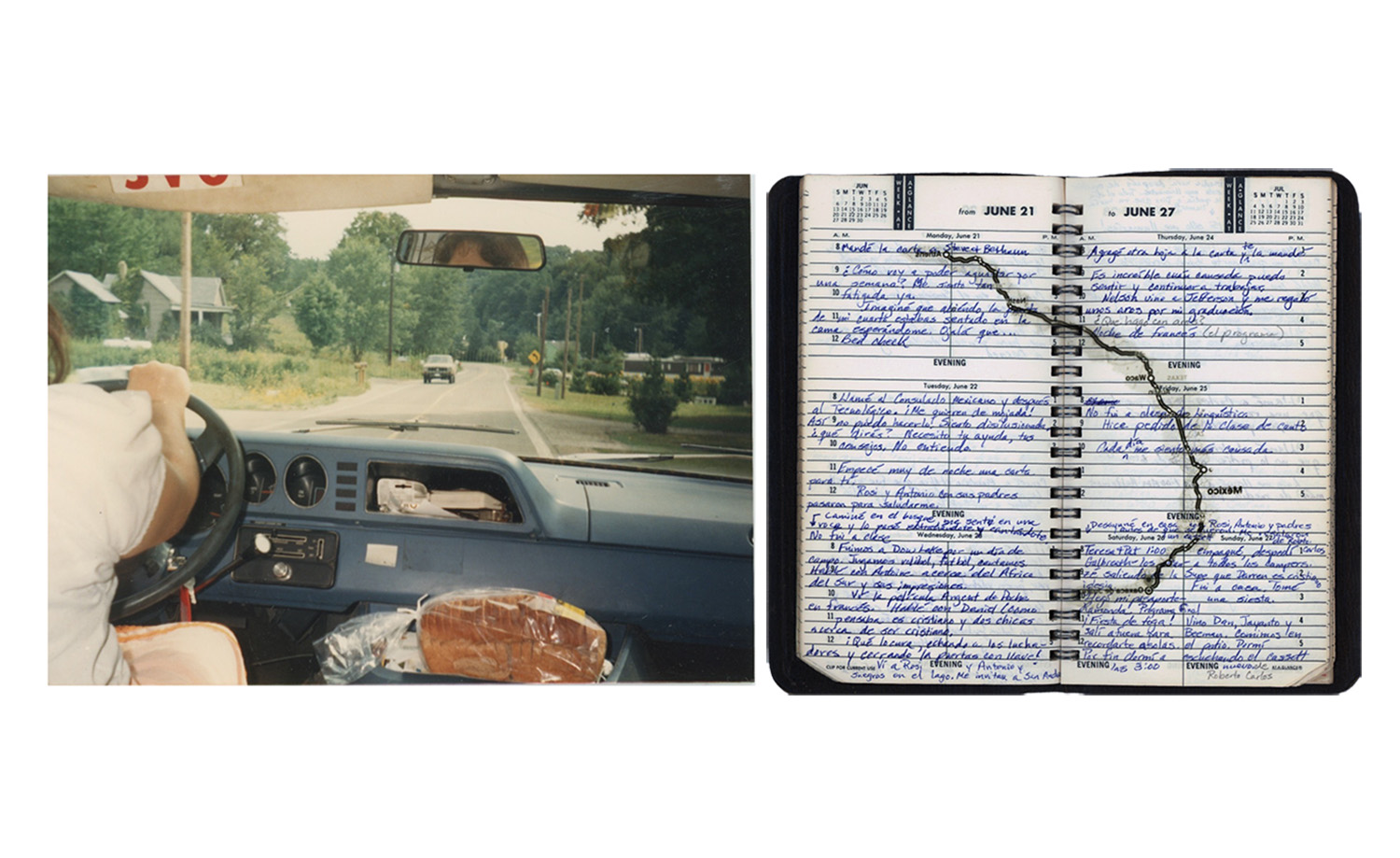

PL: Ramona was a breakaway from my documentary work. At the beginning of the pandemic, it became clear to me that looking outward would not satisfy my thirst for charting the internal landscape. Part of the creative process for this was reading my mother’s diary/planner that was chalked full of appointments, thoughts, details about every aspect of her life at the time. I realized that in many ways, I was living a parallel life to my mother’s at the time she wrote it. She and I were a similar age, both school teachers, both in love, both living between the U.S. and Mexico and missing the other. I had moved back to my hometown to teach and I realized I had started adopting habits and routines I had seen my mom do when I was a child. I also became close to her old friends. I felt this was a testament to the intrinsically linked stories that exist between those who are close to us, those who have gone before us, particularly those of our parents.

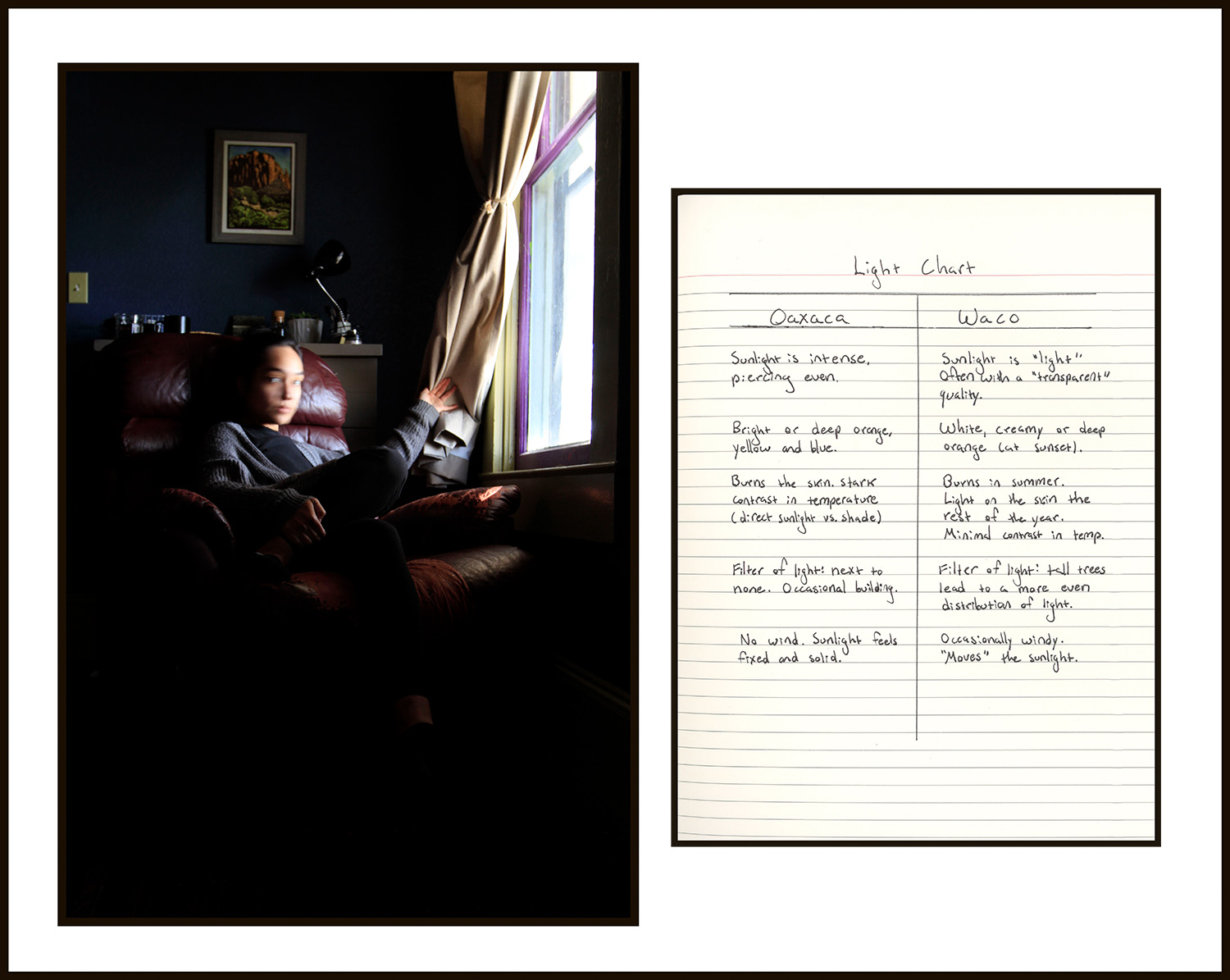

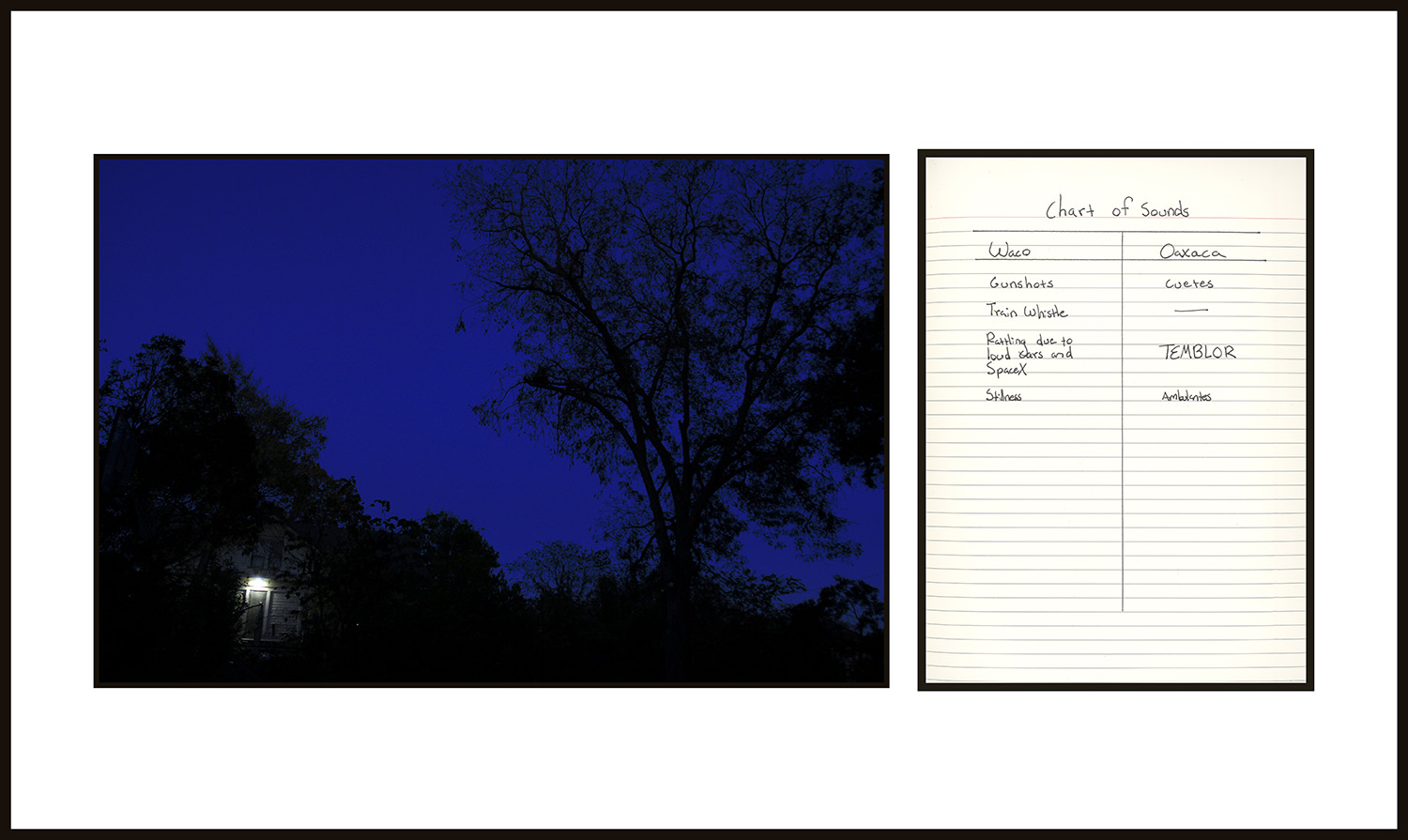

My need for personal exploration grew as I documented the cultural and geographical nuances between Oaxaca, Mexico, and Waco, Texas (both cities I grew up in and have moved back and forth from). I noticed a conversation occurring between my notes and those of my mother. I began to do the same by pairing images.

The dialogue or “third thing” created when pairing these two sets of photographs and archival material is particularly intriguing to me. How do they inform each other’s reality? How does my knowledge of a bridge between these two times and people transform how I perceive the past and current moment? How I relate to my family?

The family narrative I wish to share is one of interconnectivity that I’ve weaved through layered memoirs and chronicles that have the capacity to speak through each other, even to heal each other. I believe many family histories consist of recurrences and intentional reversal of trauma momentum, it is the ebb and flow that exists between generations.

DG: I’m curious about your choice to “deconstruct and retell” your family history. Tell us more about this, and perhaps more about your exploration and interest in memory as a construct.

PL: The construction of memory is a complex and multifaceted process, as is its deconstruction. I’ve always felt we have some power to move in and influence how we perceive the past. Memories are not stored as static representations of the past but are instead reconstructed each time we retrieve them. I believe that although we may not be able to alter the syntax of our story and that of our family, we most definitely have some power over its semantics, a sort of redemptive and creative sovereignty.

This agency can change how we relate to the past, it’s unraveling in our current lives. It has the potential to affect our relationships and perspectives about others and ourselves in real-time, and in turn, that of the people who will carry on our story into another time and place. In this way, I consider us to be carriers and alchemists of memory.

For me, Ramona achieved the impossible, creating a relationship and dialogue with my deceased mother in the different chapters of her life: as a daughter, a young woman, a wife, and a new mother. A new understanding and empathy transformed my view of her life and the characters in her life. When I use the word “retell” in this context, I’m not referring to fiction as much as I am to the liberty of narrative.

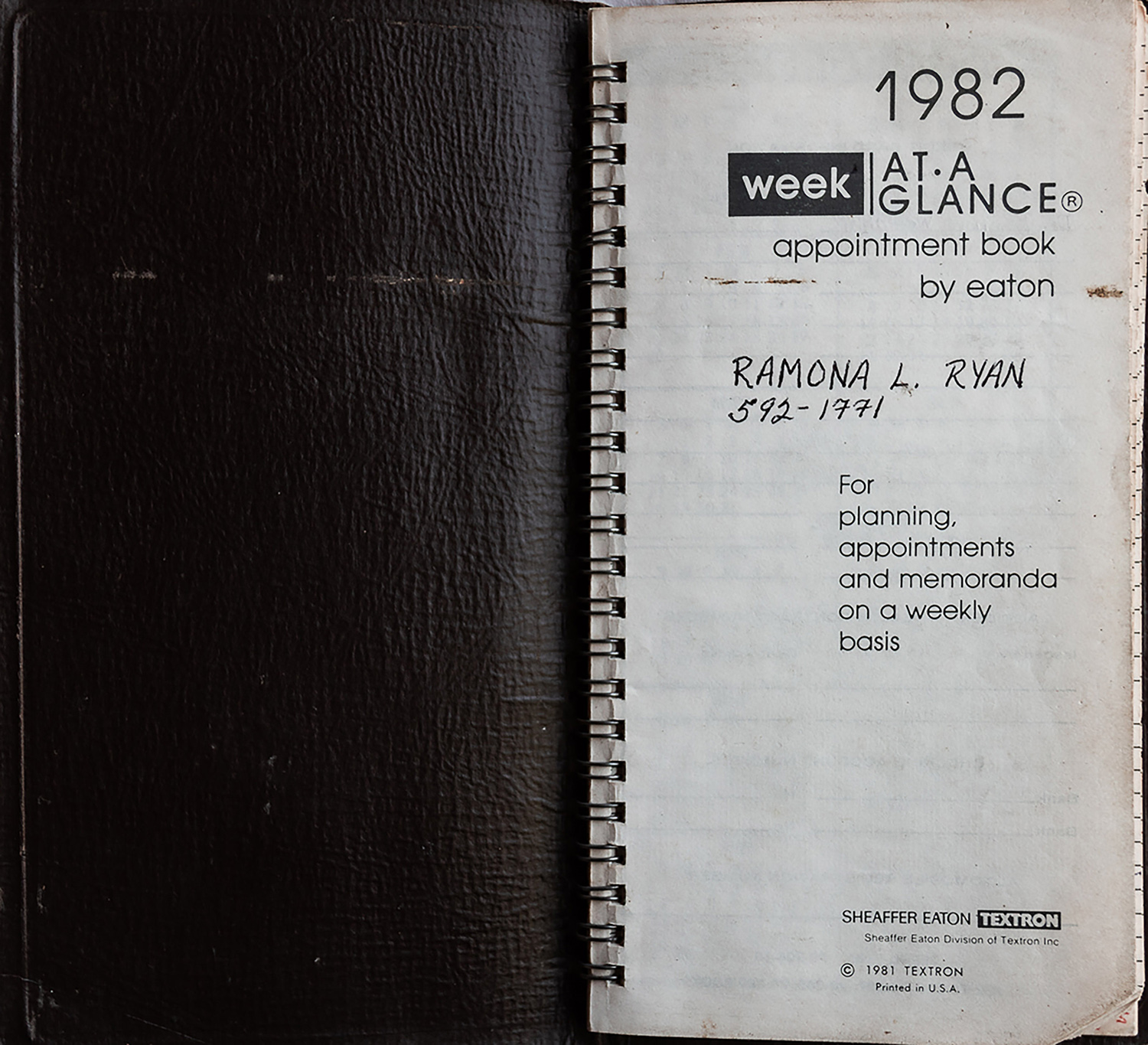

DG: I enjoy that you open this series with Ramona’s appointment book—partly because we see her name in her own handwriting (I assume), but mostly because it says, “For planning, appointments and memoranda on a weekly basis.” The word memoranda immediately makes me think of the photography’s role as a sort of reminder, albeit a fragmented one. I imagine that this spoke to you as well. What do you make of the phrase?

PL: My mother would write everything down. Unlike my father who would write pieces of information on scraps of paper he found laying around the house, my mother kept a register, a planner, a recipe book, a tax folder. The materiality of memory is something that has always fascinated me. Photography’s role in this remembrance is unique in that it has the appearance of objective legitimacy, a documentary nature that allows the viewer to believe that what they are seeing is real and unbiased. To me, it’s a container. I think memoranda is a way to keep ourselves, ironically, by inhabiting a body outside ourselves, a sort of container. However, it’s essential to be aware of the limitations when piecing together pictures of the past. How we piece those together is the art.

DG: You write that this is the first chapter of an ongoing series. Would you like to share how you anticipate it continuing over time?

PL: In October of last year, I began scanning, collecting, and digging into my father’s family history. The second chapter of this larger body of work on family archives centers around my paternal grandfather, his legacy of violence, and the trauma and collective memory surrounding it. Since I’ve started working with this archive (my paternal one), it’s been interesting to observe the difference in character and how it’s led me to new places as I attempt to work with its nature-specific challenges and tonalities. I’m not sure how many chapters this larger body of work will comprise but I’m willing to go down this path as far as it takes me.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026