Review Santa Fe: Jacob Wachal: Handumanan sa Pamilya

In mid-November 2023, I was able to spend two incredible, fast-paced days reviewing portfolios at Review Santa Fe. I was wholly impressed by the organization and implementation of the entire event. I am personally very thankful for organizations like Center that champion photographic artists and create these sorts of events–enabling career advancement and networking opportunities within the photographic community. During my time in Santa Fe, I looked at hundreds of photographs (maybe thousands?). While it was only feasible to formally review the work of a small number of participants, I wish I could have had more time to learn from at least a few more. Over the next week, we will look at the work of some artists who sat down across from me at my review table. I selected these projects because they were both visually and intellectually compelling. In the future, I am sure I will be featuring the work of many others who I met in Santa Fe, but for now let’s enjoy the work of the following, talented artists: Jacob Wachal, Sarah Kaufman, Beth Lilly, Bailey Quinlan, Harvey Castro, Jacque Rupp, Caroline Gutman, and Javier Piñero.

Today, we begin by looking at Handumanan sa Pamilya by Jacob Wachal.

Jacob Wachal is a lens-based fine artist from Lexington, Kentucky. His identity as a second generation Filipino-American heavily influences the concerns of his practice, especially in relation to the decolonization of the photographic image. His contemplative images and installed works explore overarching themes such as time, memory, and sense of place as they relate to his familial and diasporic experiences. These works seek to act as a reclamation of agency through the appropriation and subversion of historic forms and processes typically associated with imagery disseminated during the Western colonial period.

Jacob graduated with an MFA in Photography from the Savannah College of Art and Design in 2023, and his work has been included in exhibitions across the United States, in spaces such as the Center for Photographic Art (Carmel, CA), Zeitgeist Gallery (Nashville, TN), Colorado Photographic Arts Center (Denver, CO), Fenix Arts (Fayetteville, AR), and Sulfur Studios (Savannah, GA). In 2023, he received the Innovations in Imagemaking Award from the Society of Photographic Education, and was named a finalist in Lensculture’s Fine Art Photography Awards, as well as in Photolucida’s Critical Mass. Jacob is currently an instructor at the University of Kentucky.

Follow Jacob on Instagram: @wachal.photo

Handumanan sa Pamilya

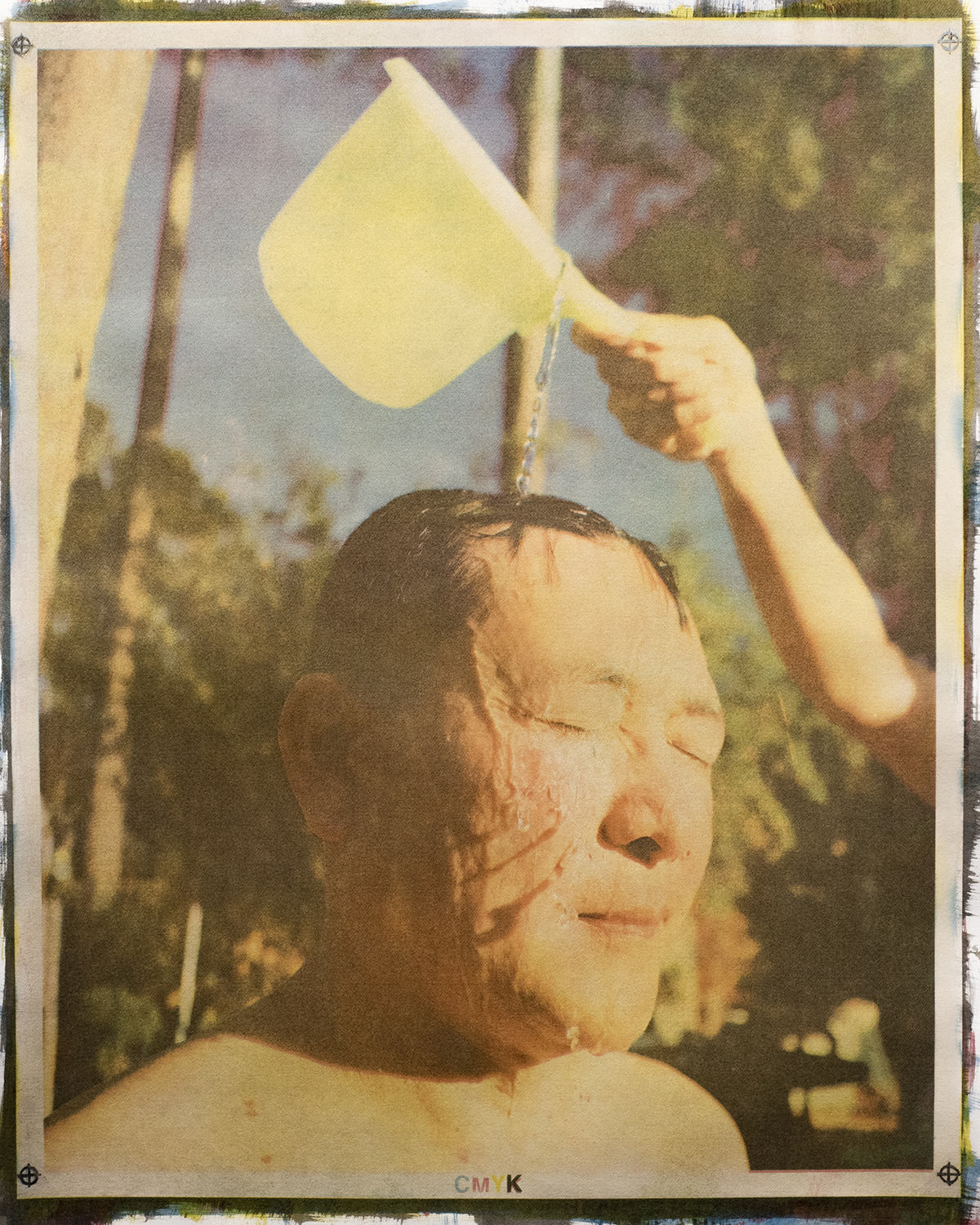

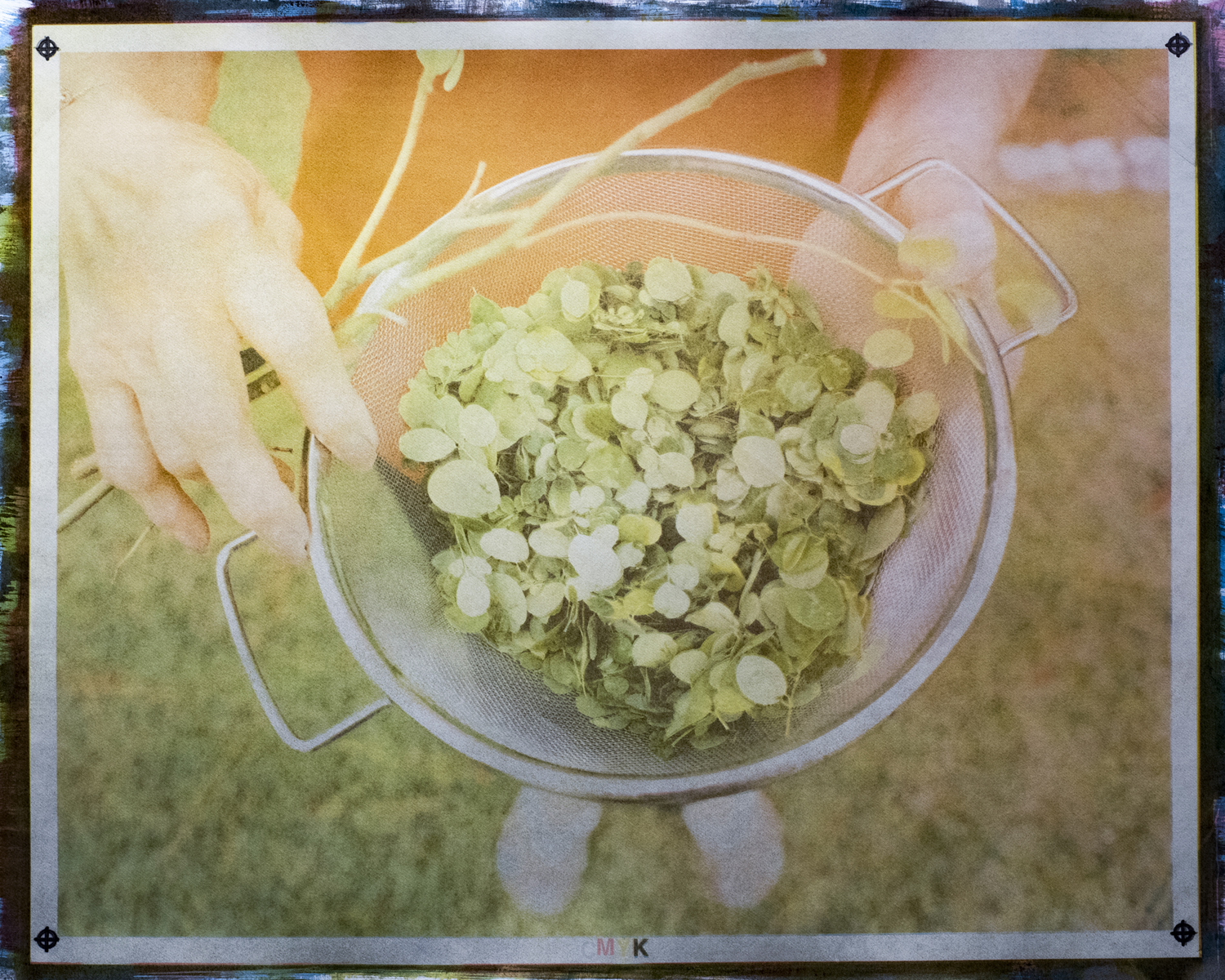

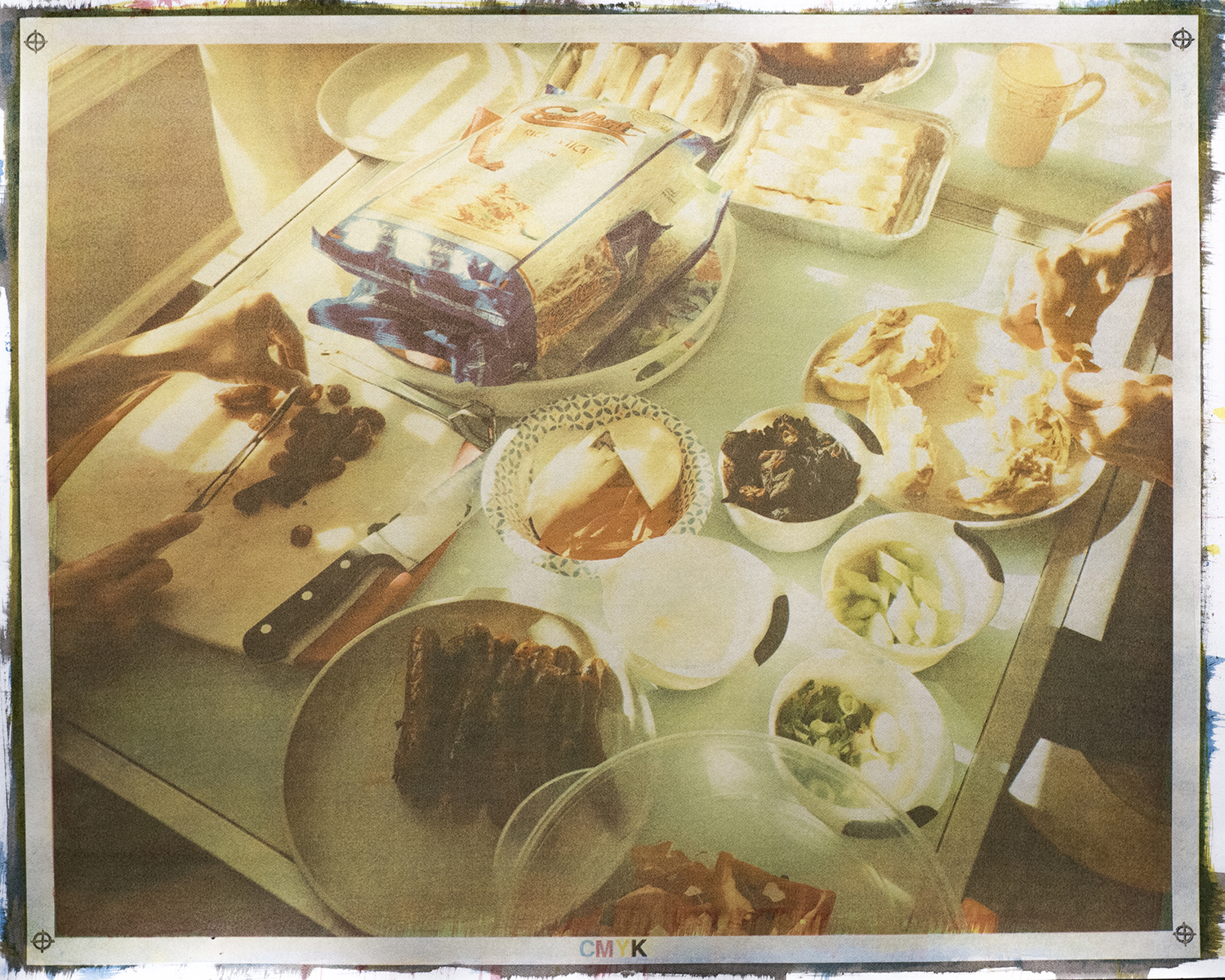

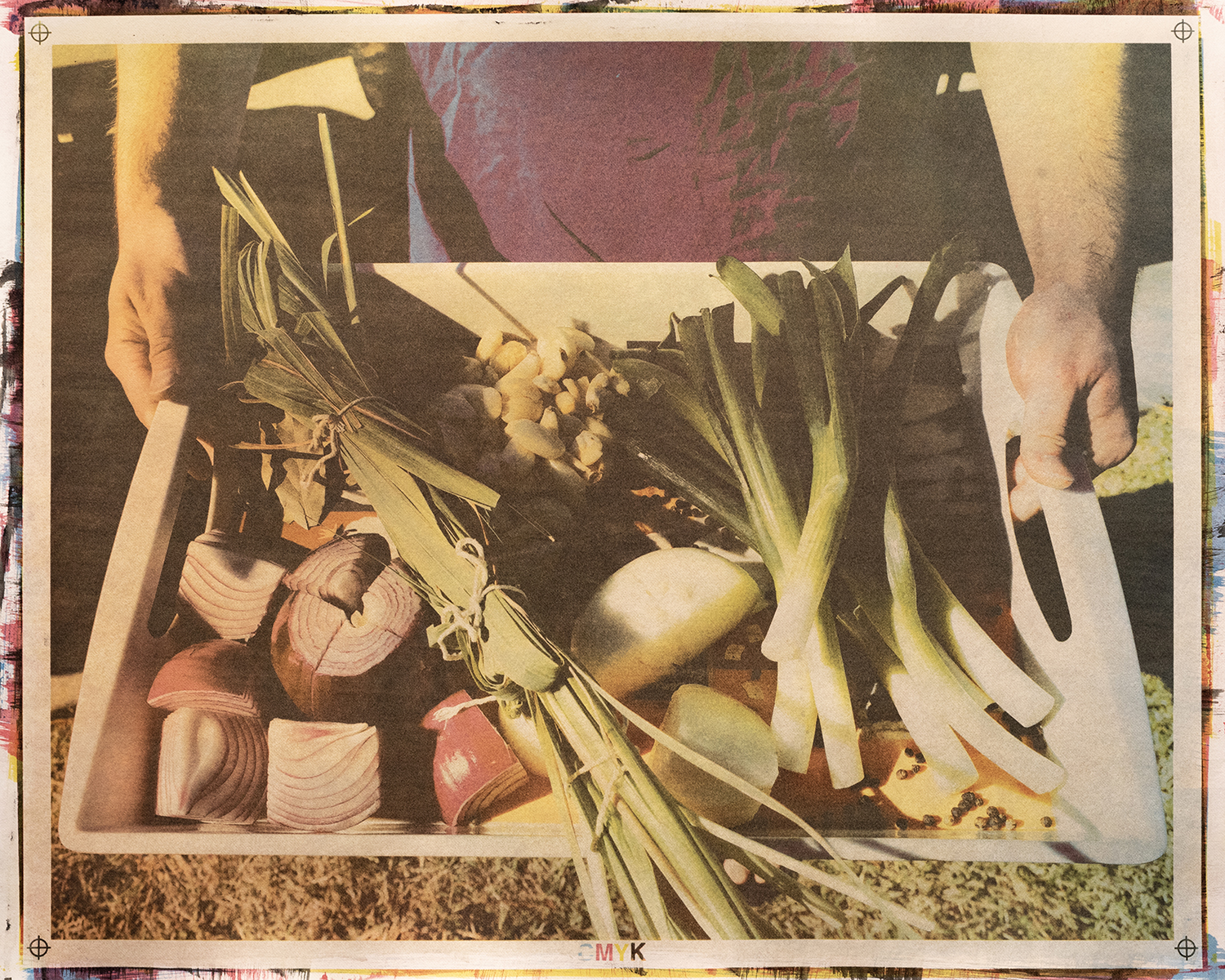

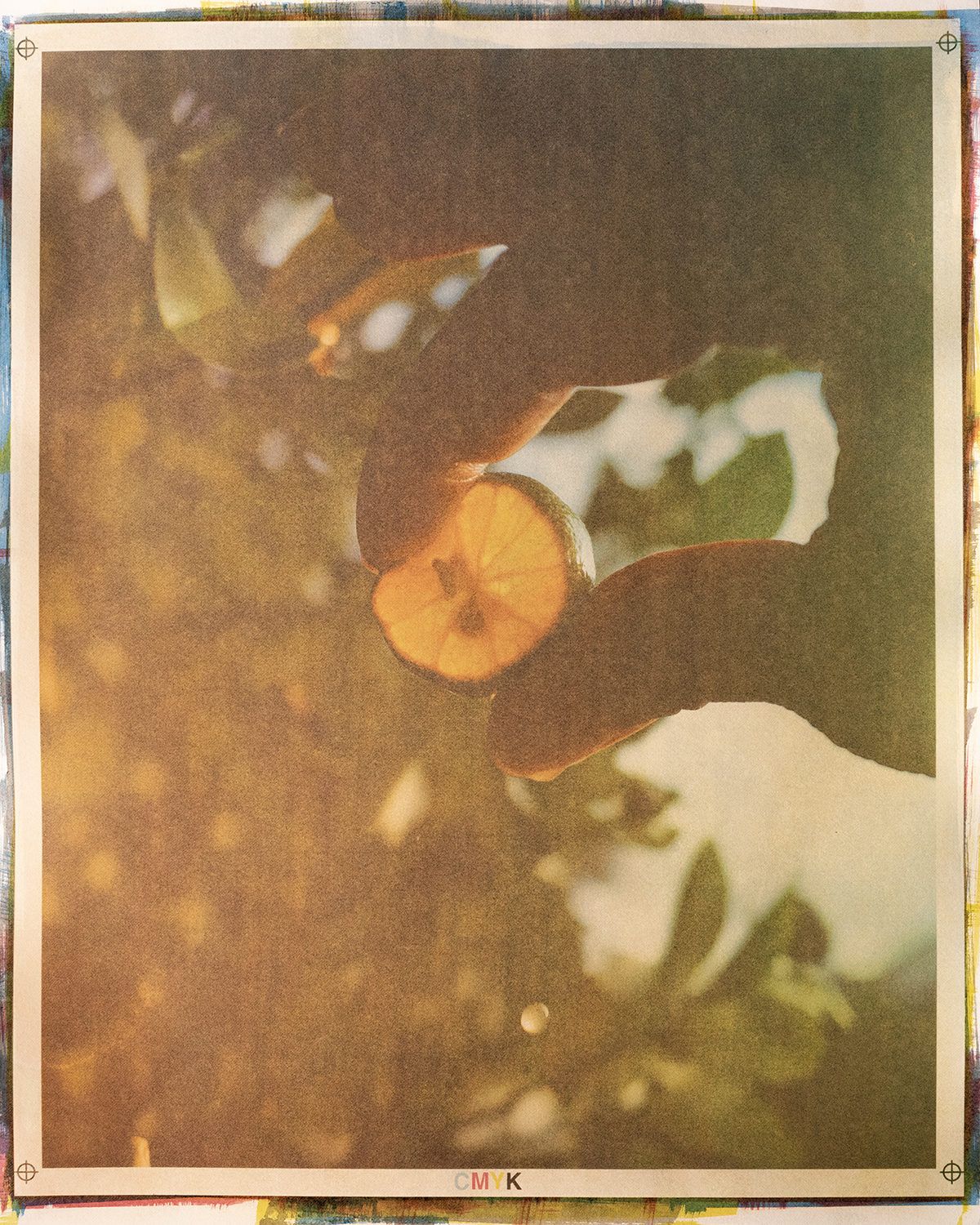

Handumanan sa Pamilya is an exploration of my identity through the visual interpolation of the memories my elders carry of their upbringing on the island of Cebu, Philippines. Each image exists as a reflection on the effects of time and place in relation to the diasporic experience; children born unto a foreign land, connected to a home thousands of miles away through the tenuous and fragile threads of memory and tradition.

Daniel George: Tell us how this project began. What led you to pursue this exploration of your family history?

Jacob Wachal: Handumanan sa Pamilya is sort of a natural continuation of research that I began during my undergraduate studies. That body of work in some ways was a surface exploration of what it meant to be a member of a diasporic group of people, mostly focusing on the act of migration and presenting it as something innately human. When I got into graduate school, I knew I wanted to continue making work about my identity, and after some experimentation with point of view and subject matter, I realized how much of my identity and firsthand understanding of what it means to be Filipino stems from the specificity of my experience within my own family, the Herrera clan, and so they became the main focus. This exploration of family history became doubly important when I started to more intensely research the colonial history of the Philippines and realized how much of this history has been lost and replaced by heavily politicized photographic archives that were in no way reflective of my family’s oral storytelling tradition, or our small collection of family photographs which survived two house fires. Understanding the fallibility of recorded history and the fragility of memory led me to undertake the role of archivist, influenced both by the desire to preserve the stories of my elders for future generations of Herreras, as well as to present a more authentic visual record of Filipino identity which stands in opposition to the colonial photographic archive.

DG: You write that this work is a “collaboration with your elders.” Would you mind walking us through that? Why did you feel it was important to work jointly in these reenactments?

JW: From my childhood, time spent with my elders was an opportunity to learn about what life was like for them in the Philippines, as well as what it was like for them to be uprooted and end up in a small Appalachian town as the first Asian immigrant family to be recorded on the census there. Prior to my career in the arts, I often took these stories for granted in some way-a lot of zoning out and nodding my head-without realizing that one day I would be responsible for keeping these stories alive. For immigrant groups that are known for their tendencies to assimilate, it is a common experience for these familial histories to be lost intergenerationally, along with language and important cultural practices. After understanding the hardships that my grandparents faced and how integral to my identity their experiences are, I wanted ultimately to provide a platform and space for them to proudly tell their stories and let their voices be heard. This collaboration involved sitting down with my grandparents, my mother, and my aunts and uncles, and talking to them about their life experiences before choosing an experience that we could work together to recreate. I would then make some compositional sketches and we would gather materials, construct objects if needed, and then make the photograph. Collaborating in this way was important and introduced a performative aspect to the work-it stopped being solely about the picture, and it allowed me to create memories of my own with them that echoed their childhood. For example, in the making of Tinikling, after hacking some bamboo poles down to size, my aunts Rachel and Leah began walking me through the steps of this traditional Filipino folk dance. Before I knew it, we had put some music on and the entirety of my family was outside and dancing Tinikling, laughing and smiling and playing, just like how they had always described it to me but I had never experienced. The resulting photograph ultimately married past and present and moved beyond what could potentially have just been an empty facsimile. In some ways, this collaborative performance also subverts the practices of American colonialist photographers in the Philippines, who oftentimes forced Filipinos into staged situations or particular dress as a way to provide pseudoscientific support for their imperial worldviews.

DG: During our review in Santa Fe, among other things we talked about language and translation—and you mentioned that you were learning Cebuano? In what ways do you think this informed your creative process while making these images?

JW: Language is integral to identity, and I think it’s a common thing for diasporic people to lose over time through the process of assimilation. Cebuano was something my mother wasn’t able to pass down to me during my childhood, due to the conditions of her own upbringing and her desires to fit in once she moved to the US. She shared with me recently how heartbroken she was when she started dreaming in English, and how she knew from that night on she would never get that part of her back. Cebuano and the other 120 or so languages spoken in the Philippines, as well as languages spoken by indigenous peoples around the world, tell all kinds of stories, both tragic and uplifting. In the case of Cebuano, Spanish and English leave linguistic evidence of colonization through various loanwords and phrases, but it also contains all kinds of information that becomes lost when translated, sort of like when you happen to overhear a snippet of a whispered conversation and are forced to fill in the blanks to make sense of it. The endurance of this language is evidence of the resilient spirit of the Filipino people, and I think it is especially evident in these words that do their best to defy understanding by those that sought its’ eradication. As an example, the last photograph in this series is titled Tanday, which can translate loosely to leg hug, or the act of resting your leg on someone you are sharing a bed with-it can also refer to a pillow you keep between your legs when sleeping on your side. In English, it loses its gentle intimacy, and a word that symbolizes closeness becomes a hollow descriptive phrase lacking emotion. Ultimately, I chose Cebuano words reflective of the imagery to help capture these nuances of Filipino-ness that might not be so easily translated, to mimic for the viewer the language barrier I encounter myself when trying to engage with my own identity, and as another performative and collaborative aspect which allowed me to sit down and spend time with my elders and actively reclaim my identity through re-learning a language we were forced to give up.

DG: You have presented this work in various formats. What brought you to the gum bichromate process, and why do you feel it is best suited for this work?

JW: Handumanan sa Pamilya, in many ways, is about looking into the past to more holistically understand the present. I knew generally that these works needed to be lens-based because of the connection between photography, identity, and colonialism. Soon after the first photograph in history was made, the technology quickly built a strong relationship with various scientific fields due to its perceived accuracy and infallibility opposed to other illustrative methods. The photograph then came to be understood as the truth, and it was not long after that this understanding of the inherent “truthfulness” of the photograph by the general public that it became weaponized in order to advance colonialist agendas. Ultimately, I began to to develop an interest in the pictorialist movement of the early 1900’s as a time period when photographers themselves were becoming disillusioned with the societal perceptions and expectations of photography, utilizing more painterly printing methods as a way to distance themselves from those that used the photographic image as a mere tool rather than a means of expression. From this understanding of pictorialist ideals, I chose to present the works as gum bichromate prints in order to join in this tradition and break away from the photographic truth-claim which was so pointedly weaponized by colonialist photographers while also visually referencing the effects of time on memory, as well as the emotional subjectivity of memory. Interestingly enough, although I initially understood the pictorialist movement as a progressive one, I soon realized that these artists, although they were rebelling against prevailing attitudes of photography in order to advance the possibilities of the medium, were doing so from a position deeply entrenched in traditional and imperialist ideals, with Alfred Stieglitz himself writing of the state of photography in the late 19th century, “Pictures, even extremely poor ones, have invariably some measure of attraction. The savage knows no other way to perpetuate the history of his race; the most highly civilized has selected this method as being the most quickly and generally comprehensible.” After reading this, the significance of choosing gum bichromate to print these photographs became greater. It became an act of reclamation through a tongue-in-cheek subversion of Stieglitz’s claim in the very medium that he saw as separating his photographs from those of “savages and fiends”, as well as a way to insert Filipino identity into a record where it has been largely absent or erased, to be considered alongside of and in opposition to the pre-existing colonial photographic archive.

DG: In your artist statement, you write that this project “seeks to engage with and question the broader consequences of colonial photographic practice.” How would you say these photographs accomplish this?

JW: We are currently living in a period in which we are collectively reconsidering our personal and shared histories. Oftentimes, this can be an act as simple as giving a second thought to something taken for granted or previously written off. Particularly with photography, it is something that has become so ubiquitous it can be easy to ignore, although it has arguably had the most substantial impact on the way that we view and interact with the world compared to any other technological advancement in recent history. I often hear the statistic that over a billion photographs are taken each day. In a time where that wasn’t the case, those with the means and the power were also the ones deciding what should be photographed and how, printing and disseminating images across the world to people that may very well have never left their place of birth, easily establishing and enforcing prevailing imperialist narratives. The effects of these propaganda campaigns didn’t just cease one day, they still often influence us, whether we realize it or not. Even the language used to describe aspects of photography imply violence-shooting, taking, capturing, etc. Alongside the commodification of images through postcards, coffee table books, likes on instagram, photo tourism, and the very idea that you can own a piece of the world or even begin to understand it through a photograph, are all symptomatic of a medium that was once used (and still is) for empire-building. I wouldn’t say outright that Handumanan sa Pamilya has accomplished more than allowing me a chance to relive and memorialize my family’s treasured memories of Cebu, but I hope the decisions that I made when putting this body of work together begins a conversation, and I’d say that’s a start.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026