Review Santa Fe: Javier Piñero: La Jaula

Over the past eight days, we’ve been looking at the work of artists with whom I met at Review Santa Fe in November 2023. To wrap things up (for now…), we have La Jaula by Javier Piñero.

Javier Enrique is a Boricua interdisciplinary artist, journalist, and writer based in NYC and the Caribbean, currently focusing on photography, text, and installation. His work explores cultural amnesia and reflective narratives about religious fanaticism, machismo, and colonial culture. He received his master’s degree in public relations from NYU.

Javier began his documentary work in 2016 as a United States Marine Corps unit photographer, documenting NATO exercises throughout the American, Asian, and European continents. As a freelance documentary photographer and writer, Javier has worked with organizations including BBC, Princeton University, El Nuevo Día, and Smithsonian Magazine, focusing on topics like food autonomy, cultural trauma, and traditional/native art techniques, having his recent photo essay, Survived by Few, published as the cover story for Smithsonian Magazine’s June 2023 issue.

In 2021, Javier became interested in self-portraiture and installation, balancing objects and narrative. In his ongoing project, La Jaula, he’s been utilizing elements symbolic of Christianity to create altars and objects that question their connection to holiness and divinity and how they affect/influence perspectives on self-liberation and social dynamics.

Javier is a 2023 artist-in-residence at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s Arts Center Residency, Review Santa Fe 2023 alum, and columnist at Puerto Rico’s El Aldoquín. In November 2023, Javier held his debut solo exhibition at Puerto Rico’s National Library and Archive. His work has been exhibited in Puerto Rico, New York, New Jersey, and D.C. and in online publications.

Follow Javier on Instagram: @javiere.pinero

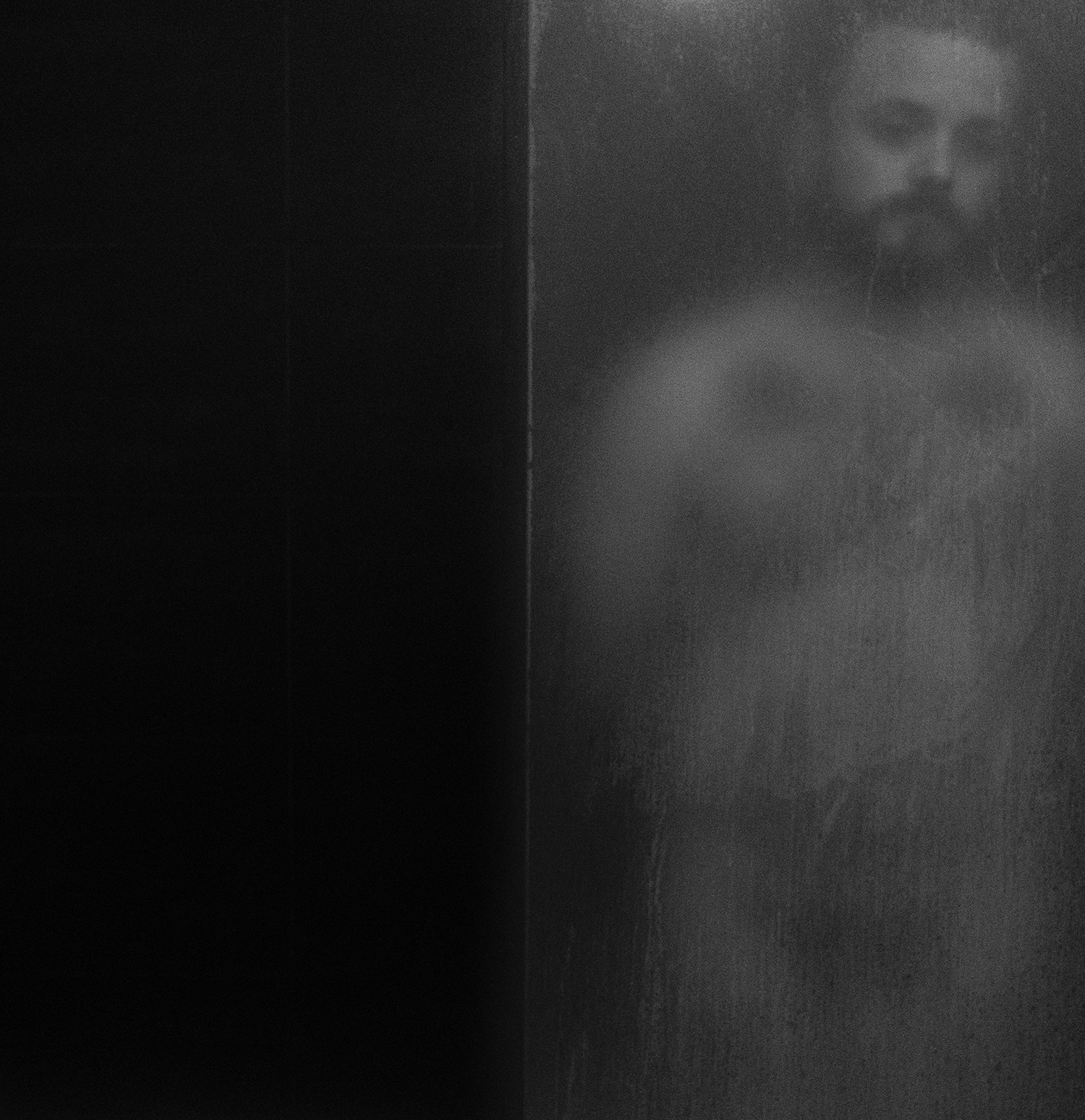

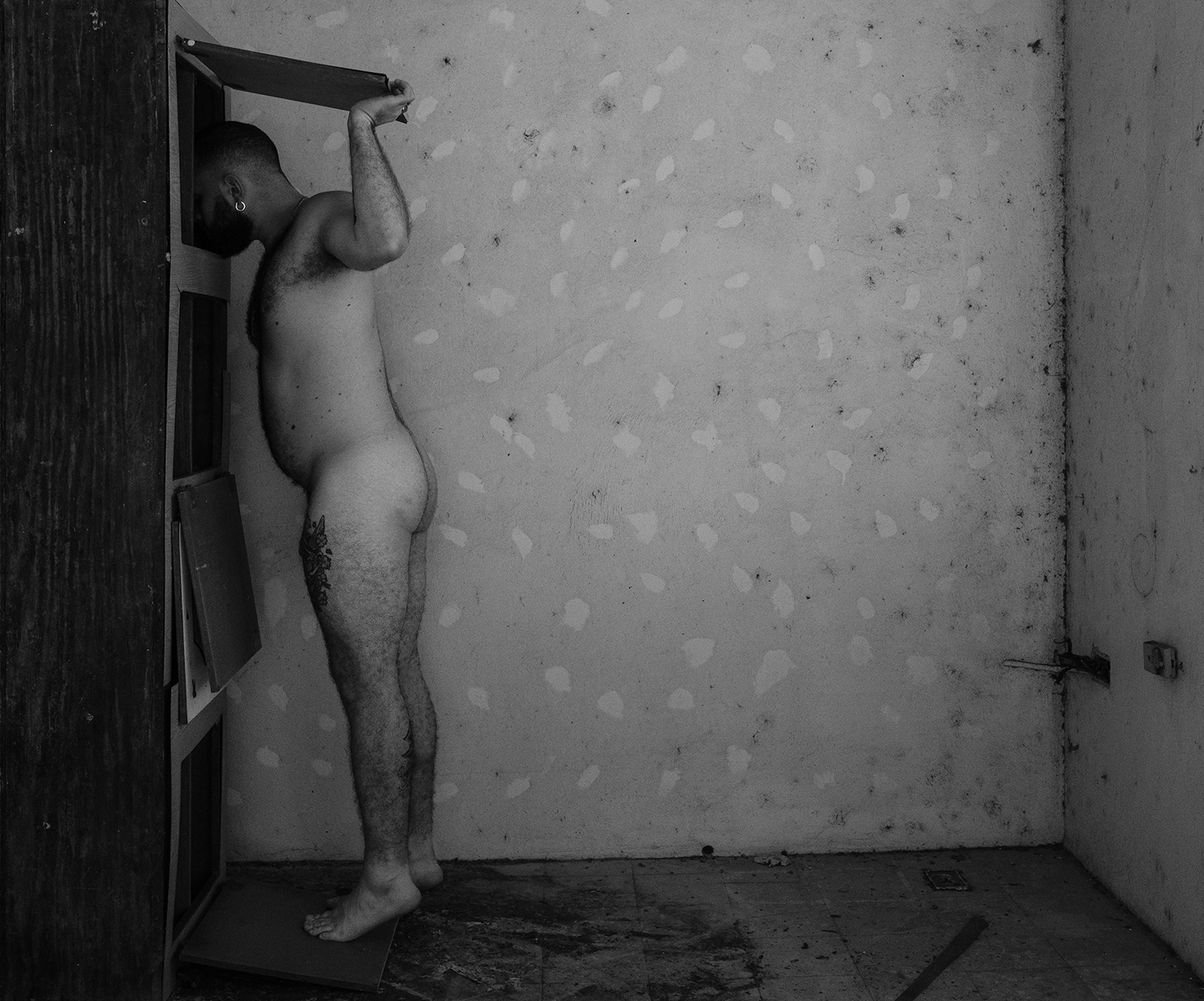

La Jaula

I make peace with the past by constantly revisiting it. “La Jaula” is an ongoing project (2021 – present) encompassing black-and-white self-portraiture, text, and installation, balancing objects and narrative, utilizing elements symbolic of Christianity to create altars and objects that question their connection to holiness and divinity. It is a reflective narrative of my experiences with religious fanaticism, machismo, and colonial culture in Puerto Rico and how they affect/influence perspectives on divinity, self-liberation, and social dynamics. Self-portraiture is central to my practice, providing a personal but allegorical quality to my photographs. They echo Francesca Woodman’s work ethic and aura in many ways, conjuring a visual poetic epic and casting myself as the central character. I write down in two languages, Spanish and English, what I cannot communicate through images, with neither language merely translating the other, but instead allowing each to function autonomously and engage in the vulnerability and semiotics inherent to their nature. The writings are short stories and journals done by hand that narrate my upbringing and point of view on my immediate family’s dynamics with religion. I bring the mediums together through rooms/stages that I then use for performance photography.

Daniel George: Tell us how La Jaula began. What brought about your interest in creating a “narrative of [your] experiences with religious fanaticism, machismo, and colonial culture in Puerto Rico”—and their resulting effects?

Javier Piñero: I began developing La Jaula in 2021. It had been a year since my move to NY for graduate school and for some reason, I began to feel lost. It was a very odd and sudden reaction. Before moving to NY, I served for four years in the United States Marine Corps as a unit photographer and I spent quite some time far from home, but I never felt alone or invisible. It seems that the feelings of isolation and emptiness I experienced came from the now indefinite point of return and having to define myself outside of a colonial system. So I wrote.

Writing has always been my place of comfort–journals only store honest conversations, there’s no need to lie when you’re speaking to yourself. During this period I wrote a lot, I wrote about my pain, about my anger. I wrote about resentment. I tried to comfort myself with the narratives and promises I grew up hearing, narratives born out of colonial trauma and fantasies offered by salesmen of the church. But god was silent here, there was only the rowdiness of the city and my thoughts. A heightened period of pain now that I lived with my colonizer. But, I gained an outside perspective and was able to recognize what was causing me disturbance.

Escaping from indoctrination is a long and tiring obstacle course. Each obstacle can represent some type of trauma like, family dynamics, male roles, social reintegration, etc. Some days they slow you down and some days you feel driven to find freedom. On those days you get to play a healthier version of yourself that courageously seeks expression. La Jaula became an unveiling process–who am I under all of these layers that hurt and weigh me down? Do I still believe there is a deity watching over me, while being everywhere at the same time? Will we ever be more than just someone’s territory? What if the male role sucks?

Translating these questions into images while challenging various societal stereotypes/standards seemed like the right answer; it brought me peace.

DG: Regarding this work’s focus on self, how would you describe the power that this method of portraiture holds?

JP: When embarking in a voyage of self-discovery, self-portraiture acts like a magic mirror that provides truth. It’s a communication tool that allows you to evaluate and decompress. If you practice it with some type of consistency, eventually you eliminate the facades and a more honest/transparent person emerges. It can be a much more comforting road to healing, or at least understanding.

Self-portraiture is rebellious and challenging, especially nude self-portraiture that steers away from eroticism. And when we stare at ourselves, ourselves completely, repressed and powerful emotions can manifest.

DG: In your statement you mention how this project is informed by that of Francesca Woodman. What drew you to her portraiture, and how would you say she influenced your approach?

JP: A year into the project I began to search for references, but nothing seemed to resonate with me. When I saw her work for the first time it provoked the same feelings my self-portraits provoke for me. Everything just seemed to click. I bought her books, I saw her documentary, and read a couple of essays, and…you know, these were real feelings and a very honest and passionate language she was using. Her work is always piercing.

It was an inspiration. It pushed me to explore my body, different forms and poses. How could I better communicate these strong feelings? It helped me understand that I was present and that captured interactions with the space and my body is a powerful communications tool. She gave me a lot of clarity.

DG: I am interested in the various uses of language that this project employs (visual, and written in both English and Spanish), and how each acts independently of the others—adding various layers of meaning. Could you talk more about this method of storytelling?

JP: There are feelings that are native to my tongue.

Writing in two languages is courageous (I believe). Allowing them to act autonomously and not rely on translations is an act of vulnerability that exposes you to different narratives of your pain. So, as I cover the walls in writing, I begin to understand the unresolved conflicts and the abandoned battlefields, and I ask, why do I hurt so deeply, and why do words hang on to those feelings? Back and forth between dots and dashes, crossed-out drafts, I drift into a place where the true stories reside—because La Jaula is a story of liberation, and it’s only fair to myself to understand as much as possible, in my native tongue, and more.

DG: I wonder if we could end by talking about the first sentence in your artist statement—”I make peace with the past by constantly revisiting it.” Artists throughout history have used creative expression as a restorative act—producing a degree of healing. Would you mind elaborating on your statement?

JP: My move to NY was as much an opportunity as an escape. I left many unresolved conflicts and thought that the distance would heal without the need for confrontation. But even at a distance, I found myself going over the traumas. On some days, I could brush them off; on others, I couldn’t even stand from the bed.

My work reflects on the past, on my upbringing, on indoctrination. When and if you can escape, you spend some time without realizing the amount of pain you’re carrying, and I know some people are blessed enough to keep going and never look back. But that isn’t my case. I pick apart the feelings of past experiences and allow myself to react. Through this process, I not only heal but understand why these phenomena still happen and why so many are trapped in these oppressive systems. The only way to understand is to visit, now in a healthier state of mind.

I make peace with the past by constantly revisiting it. Every day (and I mean every day), I think about my past, and I don’t think it’ll ever stop.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026