Mexican Week: Cannon Bernáldez

Cannon Bernáldez is acutely aware and outspoken of the ways in which sectors of Mexican society are systematically overcome by violence and collective trauma. “On many occasions, I am left speechless, but I must continue,” notes the artist. “It is a fight against the system, to continue and resist.”

From documenting crime scenes and the “war on drugs,” to working directly with the families of the missing, the photographer’s artistic philosophy is a potent tool for social critique and resistance.

Finding new pathways for inspiration after a career as a photojournalist, she now assiduously explores alternative photographic processes. This shift in practice gave rise to more contemplative work that nevertheless still maintains its critical edge and urgency — especially for those who spend their lives waiting for and demanding justice.

In this second installment of our week on contemporary Mexican photography, Cannon and I discuss the evolution of her career, from her days as a photojournalist to her current projects about survival against state negligence and identity erasure.

— Vicente Cayuela, Latin American Editor

Editor’s Note: The following interview has been condensed

and translated from its original Spanish version

for accessibility to a wider audience.

Cannon Bernáldez (1974). Born in Mexico City, she earned a degree in journalism from the Carlos Septién García School. She has complemented her artistic education through courses and workshops in photography and film criticism. Her work has been showcased in galleries and cultural centers in Mexico and abroad, including the United States, Russia, Peru, and France.

Winner of the 12th Photography Biennial in 2006, she has received the Young Creators grant from FONCA in two cycles, as well as the Cultural Omnilife Foundation Prize (2001). She has twice been a member of the National Creators System. Among her solo exhibitions are: Alliance Française Gallery, San Ángel 2003; Images du Pole, Orléans, France (2004); Nacho López, Pachuca Photographic Library (2005). Her work is part of the collection of Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland, as well as the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas, and the Arts Center at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania, USA. It is also present in the Centro de la Imagen, Carrillo Gil Art Museum, University Museum of El Chopo, and the Televisa Cultural Foundation.

She has been a lecturer at the Autonomous University of the State of Morelos in the Faculty of Arts and at the Carlos Septién García School of Journalism. She has taught courses and workshops on photographic techniques and artistic production in Mexico City and at art centers in San Luis Potosí, Salamanca, Guanajuato, and the Álvarez Bravo Photographic Center in Oaxaca, among others.

Currently, she is a lecturer at the National School of Cinematic Arts at UNAM and a member of the National Creators System. Additionally, she directs her experimental photography workshop-studio, Photo Linterna Mágica, in Mexico City.

Follow Cannon on Instagram: @cannonbernaldez

© Cannon Bernáldez, El orden normal de las cosas (detail), courtesy the Artist and Patricia Conde Galería

Vicente Cayuela: Cannon, welcome. Thank you very much for joining our Mexican Week. Your trajectory addressing complex topics in Mexican society is inspiring. How has your approach to representing violence and social issues evolved throughout your career?

Cannon Bernáldez: It has been a whole process over many years; at first, I wasn’t very clear about it, but over the years, I have worked with themes of violence. I can’t have a perspective that is detached from what is happening in my country. My work reflects my reflections and concerns about the crisis of neoliberal politics. What is happening in Mexico is very strong; my creative process also tries to understand what is happening in my country and, along with it, the role of photography in its photographic representation.

Social problems have evolved. Previously, there was no talk of femicides, racism, colonialism, capitalism, etc. I believe that our role as artists is to question and highlight through our medium what is happening in society. The role of the artist should be towards a radical imagination, beyond the canons of art, away from the market. The production should lead to a reflection of our society and the medium itself. Create to believe in new possible worlds.

VC: Your work has shifted towards constructed and staged images in the last decade. What motivated this change, moving away from the journalistic and documentary practices of your previous works?

CB: It’s about feeling creative freedom. I declared myself an artist working with the photographic medium, moving away from stale and outdated photojournalism. This artistic shift allows me to explore beyond the image, experimenting with other media like painting, film, sound art, embroidery, collage, and performance. [After I had completed] a photographic project titled Miedos (“Fears”) which involved constructed photography and false photo-documentary, I thought I was ready to return to photojournalism, but I never imagined the images I would encounter. . . Reality overwhelmed me. The scenes were harsh, intense, and I couldn’t control what was happening. I decided to approach in the most subtle and suggestive way, showcasing the remnants, the traces of violent acts.

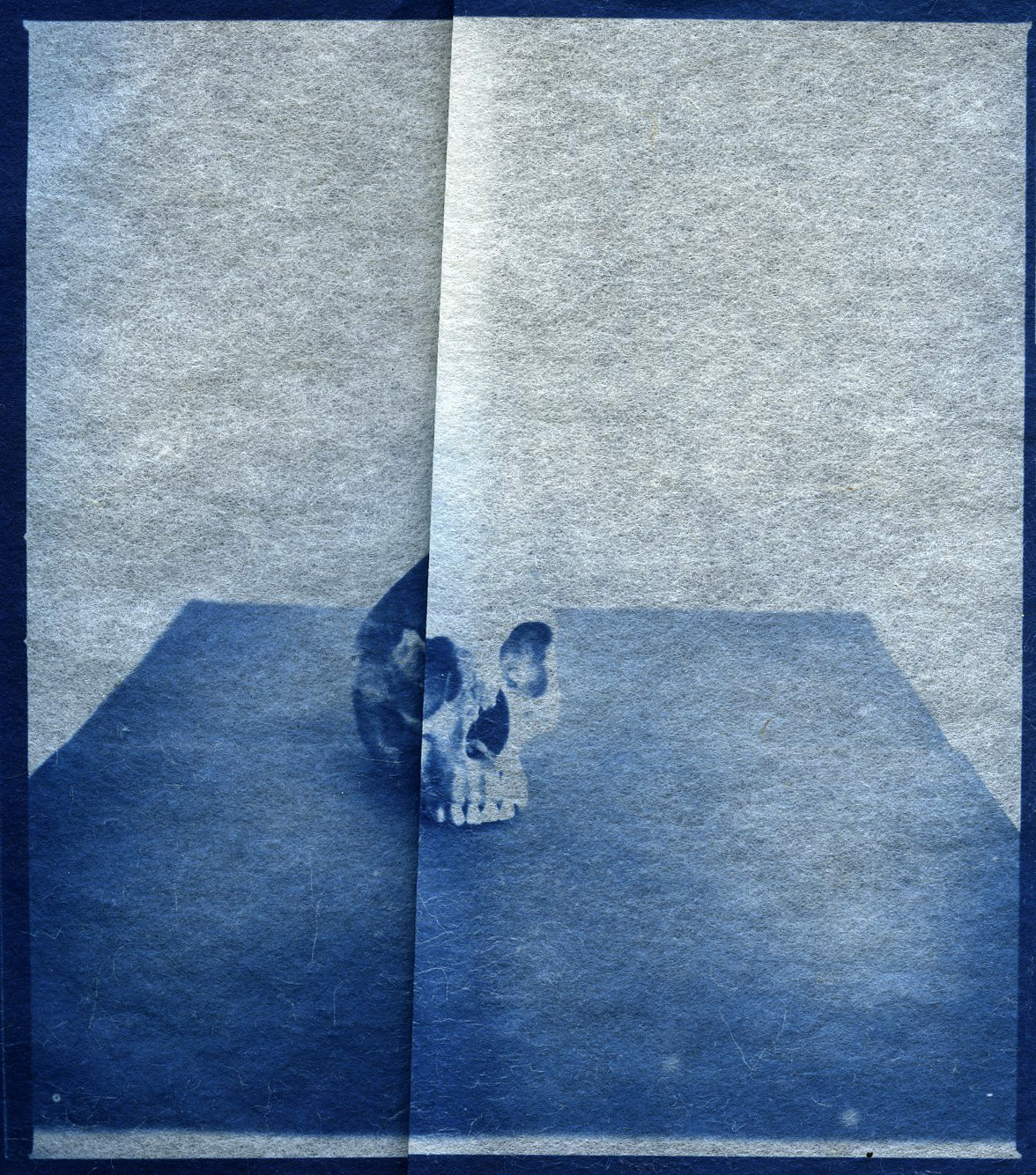

© Cannon Bernáldez, El Azul (detail), Cyanotype printed on tea leaf, courtesy the artist and Patricia Conde Galería

El Azul (“The Blue”) is the nickname of Juan José Esparragoza Moreno, the founder of the Sinaloa Cartel, who, alongside Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, created one of the most powerful and dangerous organizations in Mexico. The piece consists of around 25 printed cyanotypes in small formats on Japanese paper and tea leaves. It combines superimposed images of teeth, bones, male portraits, and old anatomy sheets, serving as visual representations of printed news, kidnapping, and testimonies of forced disappearance victims. These images also depict the search for human bones by the families of disappeared individuals, the fragility of the male body, and the infiltration of organized crime in our society. © Cannon Bernáldez, Cyanotypes Printed on Japanese Paper and Tea Leaves, 39 2/5 × 39 2/5 in | 100 × 100 cm, Edition 2/1, courtesy the artist and Patricia Conde Galería

© Cannon Bernáldez, El Azul (detail), Cyanotype printed on tea leaf, courtesy the artist and Patricia Conde Galería

VC: There is indeed a profound evolution in your approach. It is striking when we consider your past as a photojournalist, documenting violence and crime in projects like Cuando el Diablo Anda Suelto. Your more authorial projects, such as El Azul, are also concerned with the culture of fear heightened by the “war on drugs” and social violence. How do you address these themes in your images now and what still motivates you to do so?

CB: I think about subtle images without losing the main objective of showcasing violence and fear. There is a process of research and, in some cases, fieldwork and immersion. I delve into the subjects I investigate to understand what is happening with the topics I am working on. On some occasions, I gather testimonies, conduct interviews, or document my experiences with the victims. I evoke in a very suggestive manner in my images, desiring a viewer who can reflect on violence and what the victims of it go through.

VC: In spite of this change of practice, much of your work still revolves around social commitment. How did the idea of using photography and art as tools to address the situation of children and youth affected by disappearances in your project Fotografía contra el olvido (“Photography against oblivion”) come about?

CB: Just part of this struggle and resistance is the search for projects of peace and culture. Getting to know and living with the families, I realized that many of their photographs were used as denunciation posters or search cards. The photograph of their relative is their great memory and treasure.

In the workshops, we use these images for memory, we make photographic objects, like small memorials that they themselves build with a lot of love and care. These acts are a form of resistance against forgetting, it is very important to work the image from memory in order not to forget them.

Fotografía contra el olvido is also for the mothers, wives, sisters, brothers, and fathers; it’s for everyone. We make resin pendants with the photo of the missing family member. I teach them how to use the resin, and this pendant becomes their greatest treasure, as they always carry it with them. When we conduct the workshops, a space of trust and love is created for them to make their own pendant.

© Cannon Bernáldez, photograph from Fotografía contra el olvido workshop, Colectivo Uniendo Esperanza del Estado de México

VC: These are very intimate interactions with families of missing persons that you are having.

CB: Yes, it requires great respect. I try not to expose the individuals and am cautious in working with families dealing with immense pain and despair, offering solidarity and companionship.

VC: What inspired you to work with families of the missing, and why did you focus on children and young people affected by these situations?

CB: Children and young family members of the missing are silent victims, suffering alone. I aim to provide a space for play, trust, and discussion about their missing relatives. While it’s a significant endeavor and I can’t always meet the demand, it’s vital to address the State’s responsibility for restitution and support.

VC: Thinking about the lack of action from the government, how do these collectives formed by these families emerge and how do they seek support in legal, forensic, and human rights aspects?

CB: Due to the lack of support and justice from the State, families have organized themselves. The issue of disappearances is not solely attributed to organized crime but also to the government. In some cities, there are no specialized police, investigators, or forensic experts. Faced with this lack of specialized personnel, there are no searches, no investigations. Families speak of a double disappearance, as the government doesn’t assist them, and often the police are working under the orders of criminal groups. When families began organizing, they started self-educating and creating their tools and resources for field searches. Some organizations have approached them to provide legal and forensic training, resulting in a few advancements, albeit minimal. The families are aware that they must continue in their struggle and resistance.

VC: What significant impact has the project had on the participants in terms of creating visual objects loaded with their own meaning, knowledge, and memory?

CB: The idea of remembering is very important; it is significant because it is like a promise to say that they will be found, that they will continue the fight. In some instances, they give workshops to their peers; this project is no longer mine; it belongs to them. The idea is to continue with other groups, such as the families of femicide victims or murdered journalists. The victims may change, but the struggle continues.

VC: In more general terms, what challenges have you faced when working on themes like death, violence, abandonment, and desolation?

CB: The great challenge that I face is to generate subtle, reflective, suggestive images. For me, it is very difficult to think and visually solve how to represent the unrepresentable, to name what is not named, what does not manage to have a name like horror, disappearances, fear, injustice, torture, executions, the purest violence in inexplicable dimensions, executed by criminal groups supported by the state. On many occasions, I am left speechless, but I must continue; it is a fight against the system, to continue and resist.

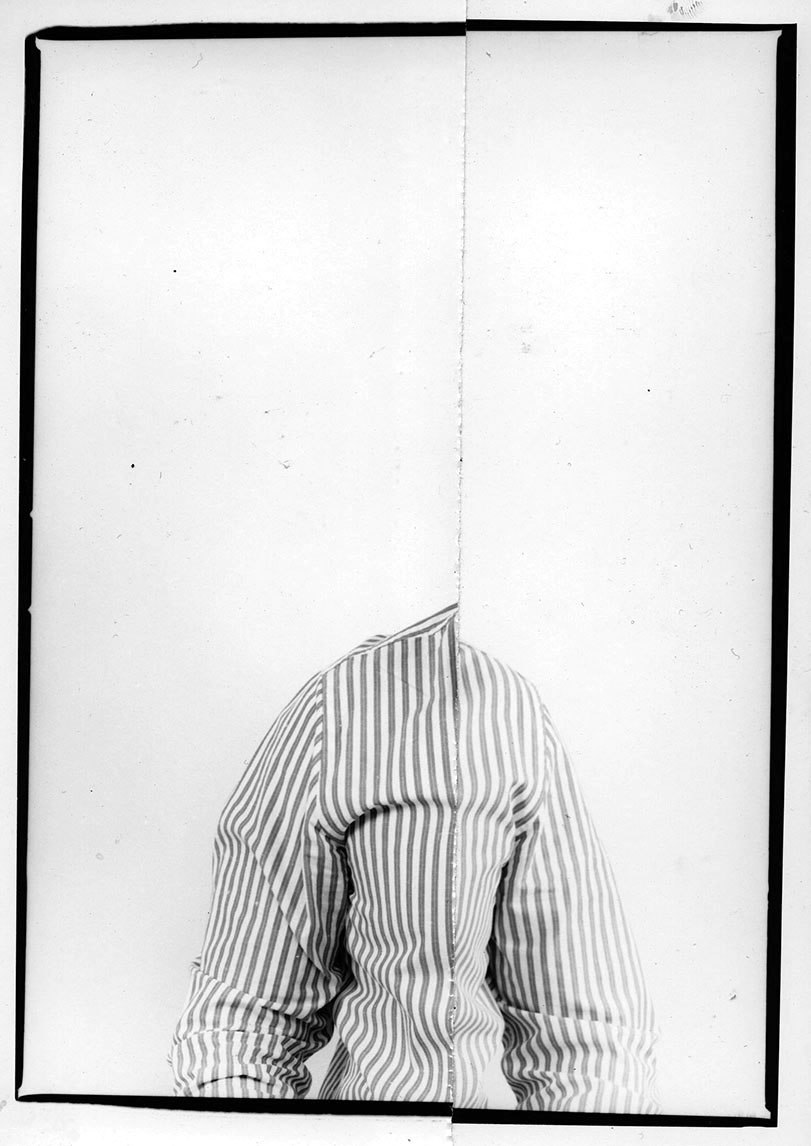

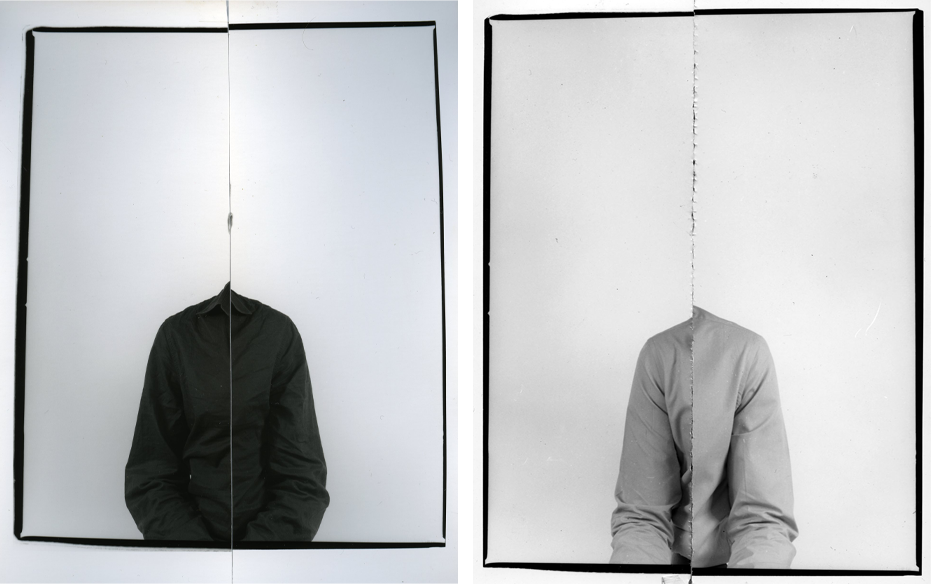

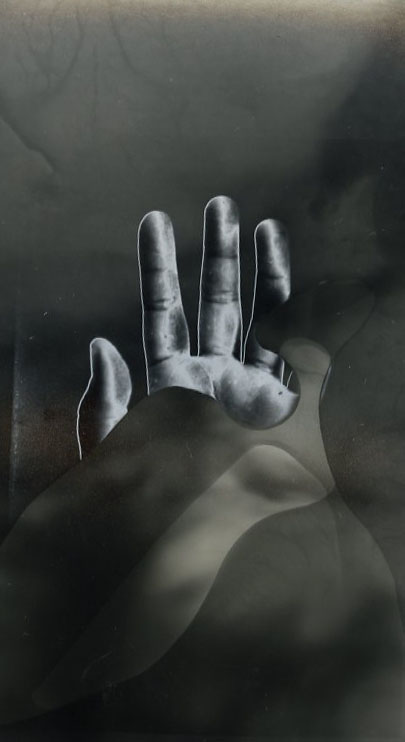

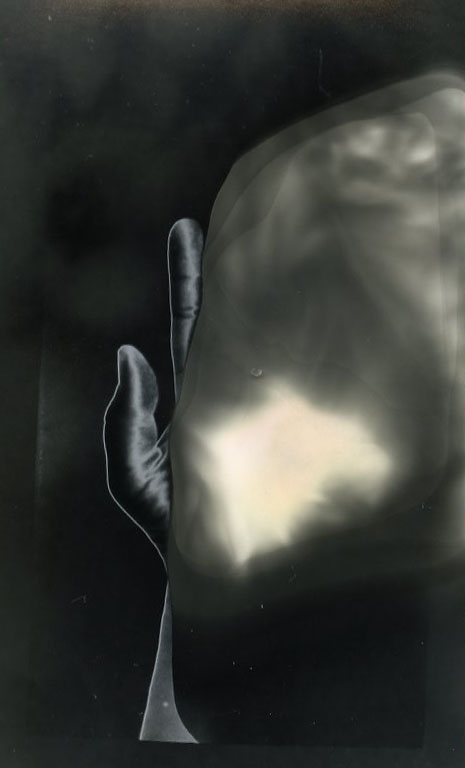

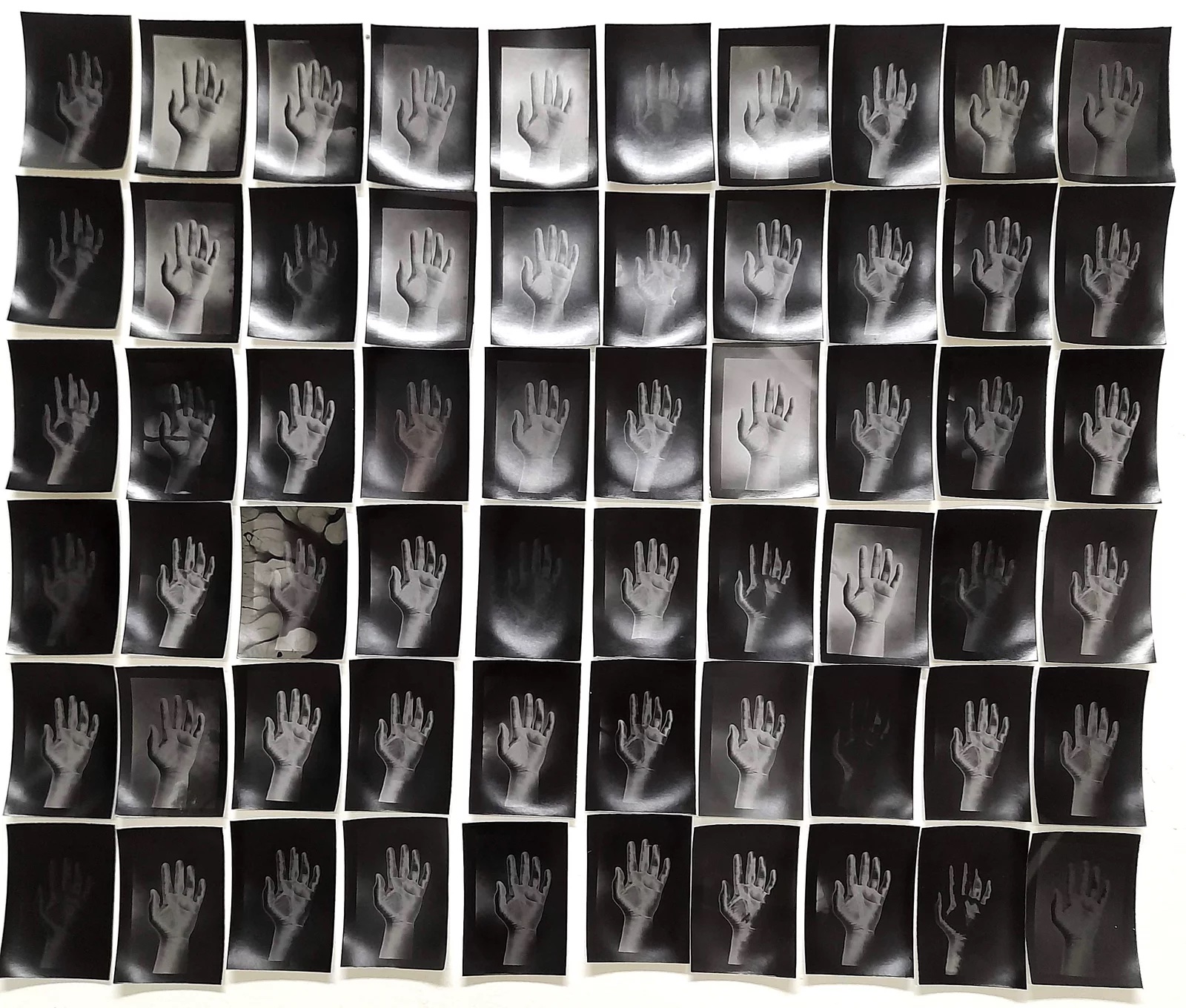

© Cannon Bernáldez, El orden normal de las cosas, detail, solarized gelatin silver print 31 1/2 × 46 9/10 in | 80 × 119 cm, frame included, edition 1/1

© Cannon Bernáldez, El orden normal de las cosas, detail, solarized gelatin silver print 31 1/2 × 46 9/10 in | 80 × 119 cm, frame included, edition 1/1

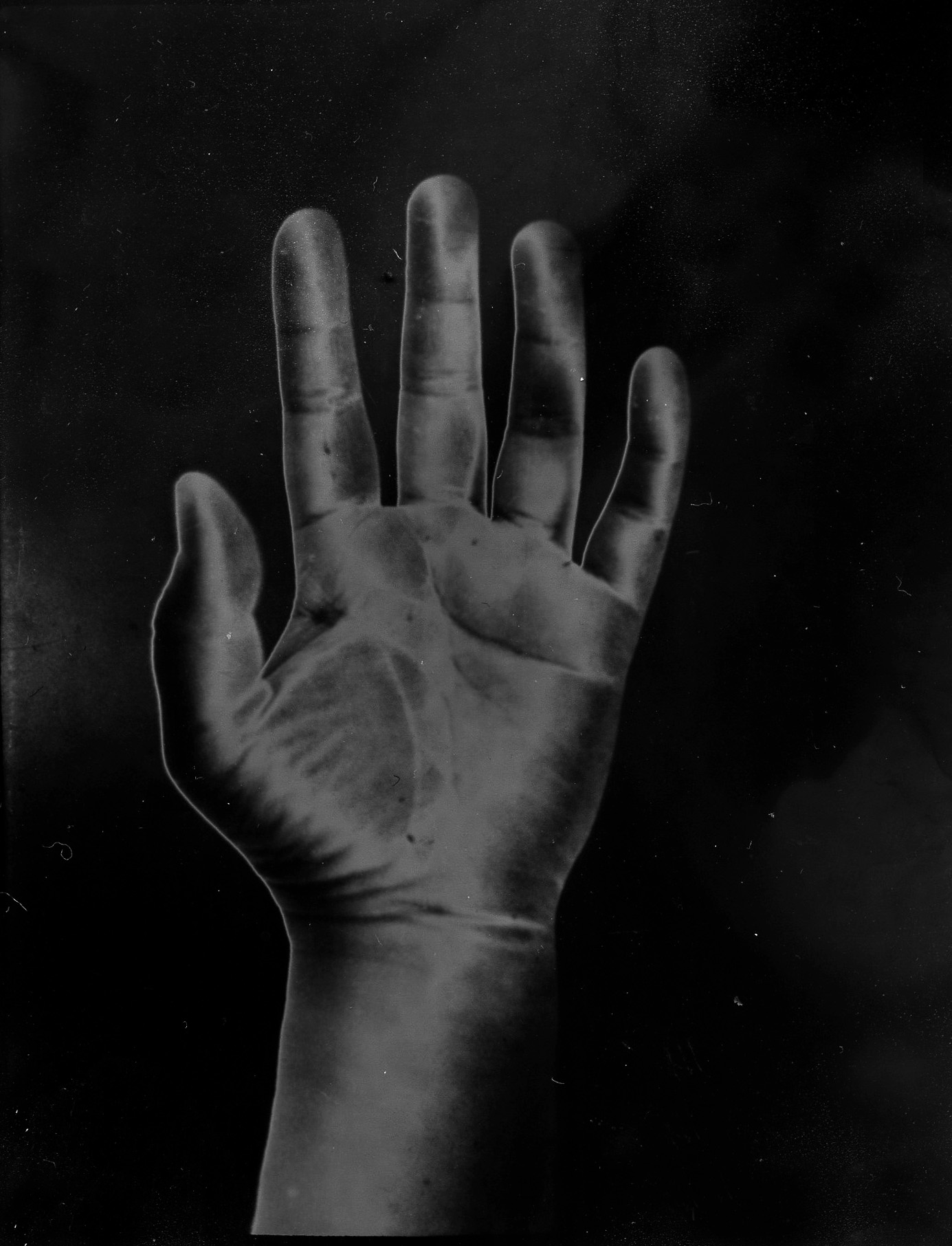

VC: You not only address these issues externally through society. More recently your work has taken a more vulnerable, autobiographical undertone. In El orden normal de las cosas, you explored creating a series of photographs of your hands, printed on solarized silver gelatin, after a very traumatic event in your life. Could you provide more details about that and the concept behind this work?

CB: In 2021, I was assaulted in Mexico City, receiving a blow to the face that caused me to fall, resulting in a small fracture in my left hand. For days, my face was deformed from the impact, and my hand was in bad shape. I filed a report and sought help from the state, such as filing a report and medical attention, but I found none. I was alone and felt ashamed. The state re-victimized me, and I found no justice. The only thing that occurred to me was to take photographs of my hand. My body was broken, battered, and in pain. Once recovered, I began printing and experimenting with photographic printing in my home lab with small photographs using the solarization technique. I have a small lab in my house that I set up during the pandemic, allowing me to make small prints. I started printing impulsively; my hand was the representation of that pain, deformed and broken, resulting in more than a hundred prints. There could be more, as it represents the constant search for justice and redress that the state did not provide me.

© Cannon Bernáldez, El orden normal de las cosas, detail, solarized gelatin silver print 31 1/2 × 46 9/10 in | 80 × 119 cm, frame included, edition 1/1

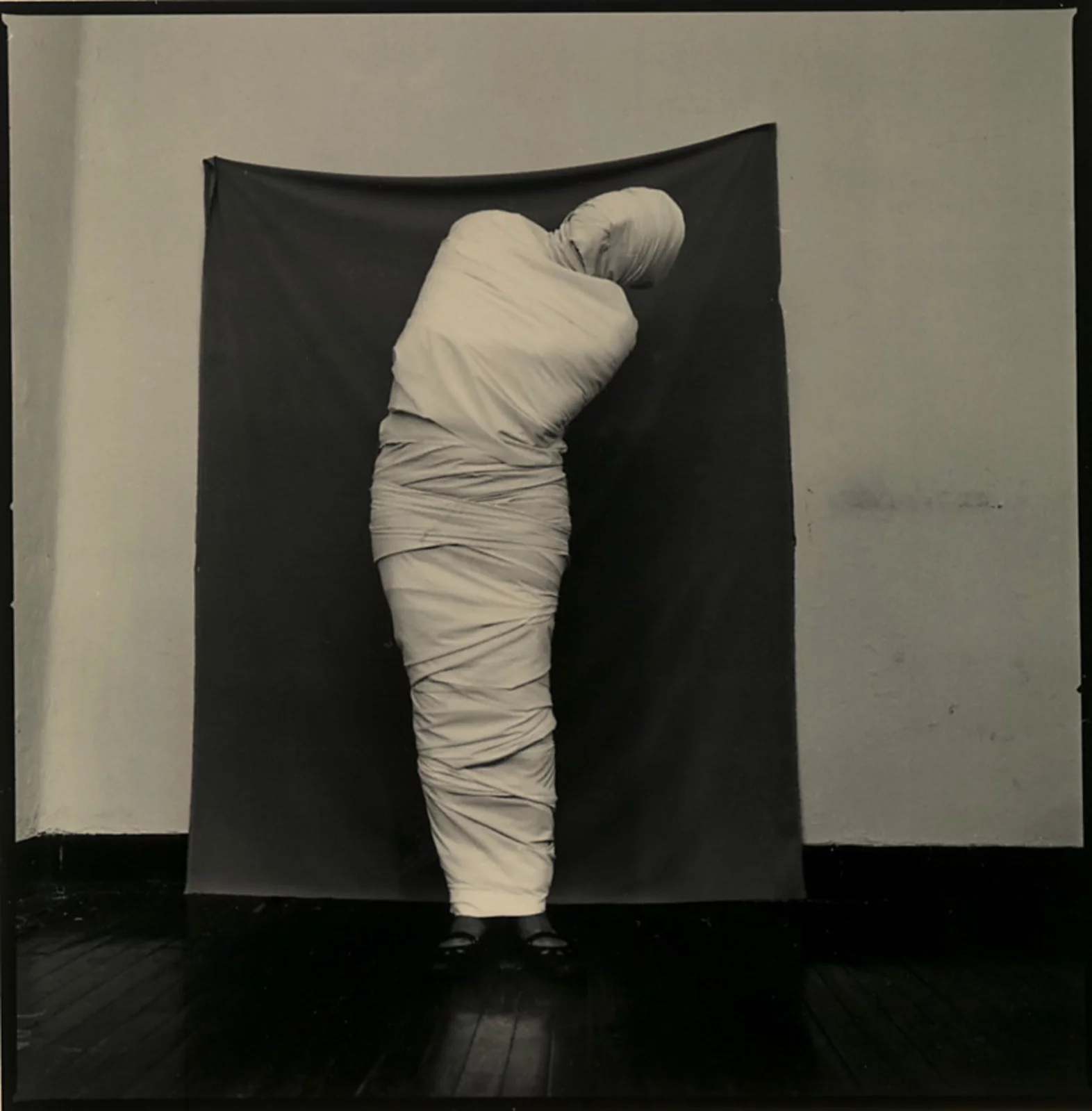

VC: Miedos (“Fears”) is another authorial project that is also more internal, featuring self-portraits and staged scenes where you enact your own death, exposing personal fears and phobias. How do you use the combination of fiction and reality to convey messages and emotions in this work?

CB: I have visual references that have helped me construct my images, such as childhood stories like The Wizard of Oz or Alice in Wonderland, along with violent newspaper images. I am drawn to fantasy and bucolic images. My academic background is in journalism, and I did press photography and documentary projects. During that time, I believed the model of documentary photography was exhausted, and I should try combining documentary and fiction, creating false documents. I focused on making images that appeared real, from their atmosphere to the final result. I wanted them to look old, so once printed, I toned and sepia-toned them with coffee. I submerged the prints in coffee to give them that antique and vintage tone. In the end, I had to show myself as I was. I tried to connect with the viewer in the clearest, but above all, honest way. I believe many people fear being run over or having their body found in the field—a reality that can happen to anyone in contemporary Mexico.

© Cannon Bernáldez, Untitled, 2010, Silver gelatin print toned with coffee, 4 1/10 × 4 1/10 in | 10.5 × 10.5 cm, Frame included, Edition of 10, courtesy the artist

© Cannon Bernáldez, Untitled from Miedos, 4, 2005, Silver gelatin print toned with coffee, courtesy the artist

VC: Now let’s talk about your background. How did your family environment and the sociocultural situation in Mexico City influence you as a photographer?

CB: My father was an amateur and self-taught photographer; he made his own lab, built his enlarger with a slide projector of the time, and also prepared his own chemicals. There are some prints he made and a couple of cameras. When I was born, his hobby had ended, and for some strange reason, he named me Cannon, which I understood was after a Goddess of Mercy in Japan.

My environment was more influenced by my older sister, as from a young age, she attended cultural spaces and read many newspapers and magazines that were critical of the State. There was a newspaper called “La Jornada” which published incredible everyday life photographs, it was a great visual reference. I remember that as a teenager, I would look at it and wished to be a press photographer.

At that time, the state began to give more space to Mexican photographers, the 150th anniversary of the arrival of photography in Mexico was celebrated, and several exhibitions were organized in some museums, and of course, the foundation of the Centro de la Imágen in Mexico City in 1994. This space, dedicated exclusively to photography, had a huge influence on my life and training. It determined my perspective, as I met great people, from historians and curators to artists, etc. I learned another way of doing photography.

VC: How would you describe your evolution as a photographer over the years and the challenges you faced at the beginning of your career?

CB: My evolution has been to understand my own creative process, to be very respectful of my process, but above all, to be honest with myself. My training was in journalism, a profession where objectivity was a key point for its practice. I decided it was not my path, and that was when I gave way to imagination, play, the unexpected, chance, experimentation, and the alternative. I wanted to develop my own style, reflective and sometimes irreverent and radical. It has been very hard work because I deal with complicated themes such as violence, death, desolation, and abandonment.

The difficulties I faced were understanding and getting to know this complicated photographic language. Thirty years ago, there weren’t as many photography schools in Mexico, only a couple, and there was no space for reflection and analysis of the image. That is, one could not think of the photographic image from another perspective, other than social photography. It was not until the foundation of the Centro de la Imagen that I could learn and discover new forms of production. My current challenge has been to think of photography beyond photography itself.

© Cannon Bernáldez, El orden normal de las cosas, detail, solarized gelatin silver print 31 1/2 × 46 9/10 in | 80 × 119 cm, frame included, edition 1/1

VC: Cannon, thanks once again for joining us. I have one last question for you. How has photography changed since your beginnings in the medium, and how do you think this affects the construction and appreciation of photographic culture?

CB: [Photography] has changed in ways I could have never imagined, the immediacy, the viralization, and other concepts that are linked to photography. Nowadays, memory is immediate and ephemeral; no longer do we talk about light, silver, chemicals, archives, there are other devices and other generations. … The only thing I believe we must keep in mind is our capacity for doubt and reflection.

Never before have so many images been produced as in this era; thousands and millions of images circulate daily. Moreover, with the arrival of Artificial Intelligence, the risk is even greater. There is no visual education. It is only recently that there has been talk of colonialism, racism, indigenous peoples, radical far-right groups, etc. Our culture has been visually subjected to colonialist and exotic gazes.

Never before had we been able to access intimate spaces, the residences of artists or the extreme luxuries of famous influencers; the private became public. We have aspirational, false images that reflect a perfect world. In political campaigns, we talk about digital armies, a whole arsenal to discredit the opponent; now more than ever, we must be alert.

There is such an abundance of image circulation and so much immediate stimulation that we have stopped contemplating, looking beyond. We need to return to manual processes, not out of resistance to technology, but to return to other ways of relating to the world. Our reality is filled with screens and phones. We need time to get to know ourselves and create imaginaries of resistance against this overwhelming digital reality.

Vicente Cayuela is a Chilean multimedia artist working primarily in research-based, staged photographic projects. Inspired by oral history, the aesthetics of picture riddle books, and political propaganda, his complex still lifes and tableaux arrangements seek to familiarize young audiences with his country’s history of political violence. His 2022 debut series “JUVENILIA” earned him an Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the Saint Botolph Club Foundation, a Lenscratch Student Prize, an Atlanta Celebrates Photography Equity Scholarship, and a photography jurying position at the 2023 Alliance for Young Artists & Writers’ Scholastic Art and Writing Awards in the Massachusetts region. His work has been exhibited most notably at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally in print and digital publications. A cultural worker, he has interviewed renowned artists and curators and directed several multimedia projects across various museum platforms and art publications. He is currently a content editor at Lenscratch Photography Daily and Lead Content Creator at the Griffin Museum of Photography. He holds a BA in Studio Art from Brandeis University, where he received a Deborah Josepha Cohen Memorial Award in Fine Arts and a Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography.

Follow Vicente Cayuela on Instagram: @vicente.cayuela.art

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026