Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan Parker

In expanding our celebration of Earth Week, Earth Month: Photographers on Photographers will focus on the work of Eco.Echo Art Collective, a group of international artists deeply concerned with the well-being of our planet beyond human needs. The group’s concerns are climate change and anthropogenic activities’ global impact. Driven by an appreciation for the natural world’s beauty, diversity, and wonder, they believe in the inherent worth of all living beings regardless of their instrumental utility in fulfilling human desires. This week, members of Eco.Echo Art Collective will take time to reflect on each other’s work and how the transformative potential of photography can engage in challenging conversation and affect social change around ideas of humans and our surroundings.

Today, member J Wren Supak will share her discussions with member Ryan Parker.

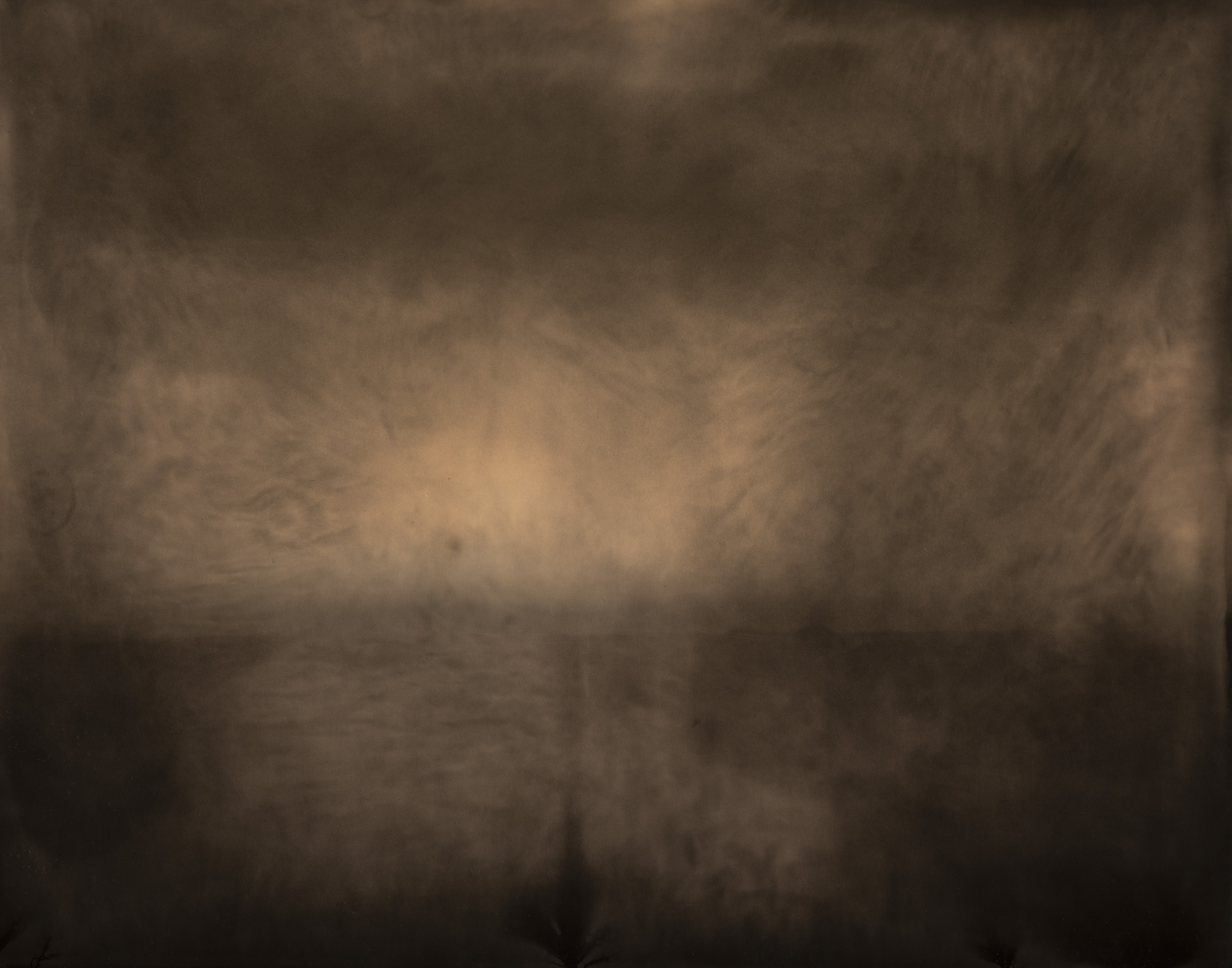

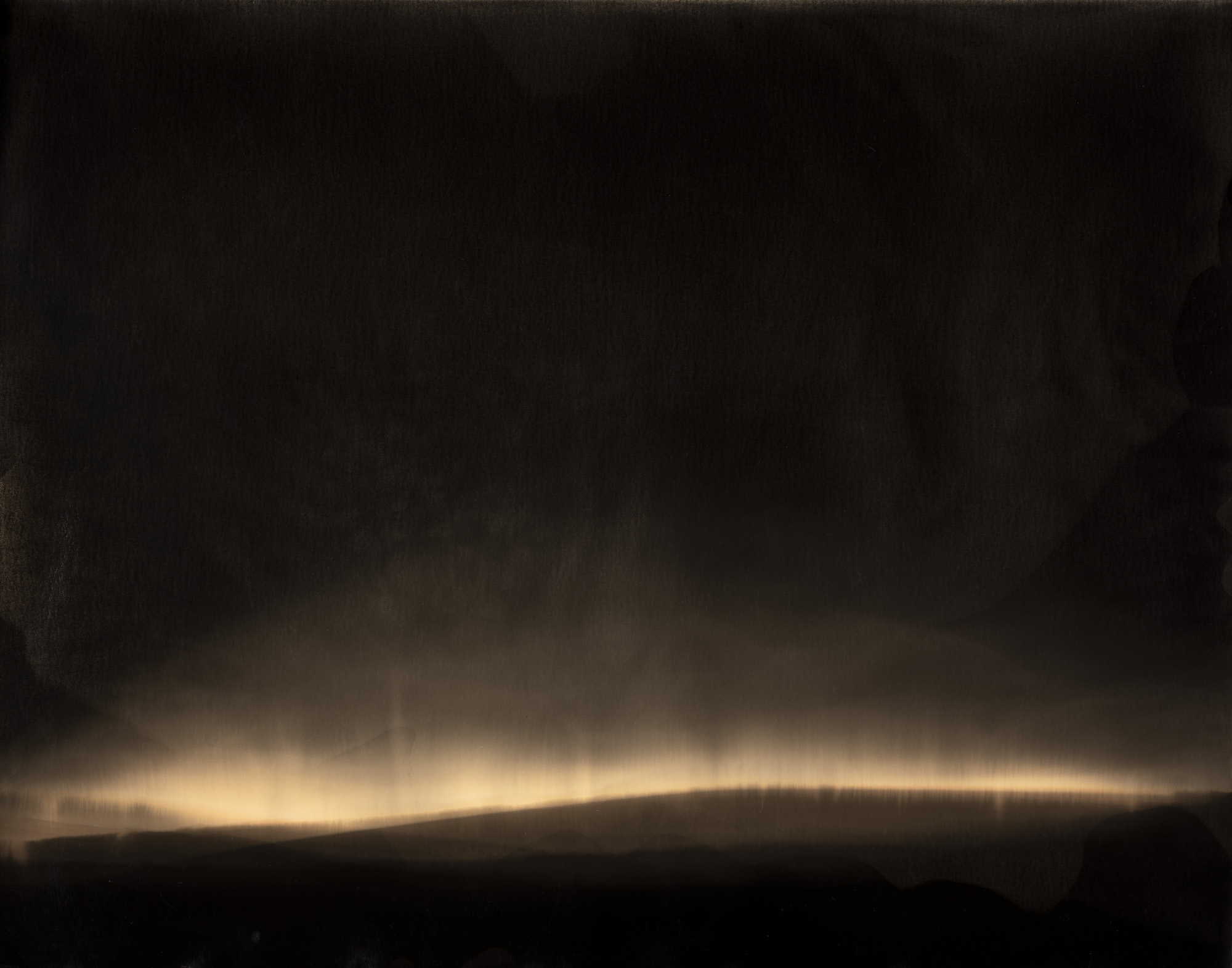

It is April, the awakening of Spring, and time to consider new ideas. I have had the pleasure of interviewing photographer Ryan Parker. Ryan is a technical photographer, dedicated to the practice. His images include painterly qualities—echos of minimalist and color-field or industrial abstraction imbue his compositions. Even a little James Abbott McNeill Whistler characterizes his chemigrams. I find that these are signifiers of his explorations of the implications of deep time on humanity. When I look at Ryan’s photography, I see a person looking at humanity’s influence on nature, interpretations in simple phrasings. His desolate landscapes are lonely, with occasional suggestions of irony without cynicism. Ryan is an intentional photographer. He uses his technology to compose images and develop or create them stylistically. His photographs stop short of self-consciousness and rest in a manner of showing- and -telling. This takes thought, planning, execution, skills, curiosity, and hopefulness.

We should also congratulate him on his nuptials! When we were interviewing, Ryan and another photographer and Eco.Echo Art Collective member Jessica Hayes, got married! They met when they were separately photographing the Spiral Jetty.

J Wren Supak: What threads your bodies of work together?

Ryan Parker: At its core is a love of community and culture. Though I don’t make many portraits these days, I’ve been preoccupied with the land. In Montana, so much beauty is counterbalanced by so many violent disruptions to the earth. The way we use this beautiful land and what it reveals about us have kept my attention for the past few years. Within each project, there are questions about land use, ecology, deep time, and our interactions as humans with the earth.

JWS: What do you mean by deep time? (which photo expresses deep time to you most)

RP: Deep time is a useful way to consider longer time scales then humans traditionally can do. It was coined by John McPhee, if memory serves, and refers to thinking of things through a geologic time scale rather than a human. Millions and billions of years vs hundreds of years. My interest in it comes from thinking about the entomology of terms often used to describe the land. We have language to describe erosion made by wind, eolian. We also have words for human-made marks on the land, such as ditch, culvert, and berm. But what of the human-made marks will last thousands of years? What do we call a mound of earth covering nuclear waste or a pile of slag a hundred feet high? This is a question I spend a lot of time thinking about. There is an image I made of what looks like a mountain peak. But upon closer look is an enormous pile of slag. I wonder, in a hundred years, what will be called such mounds of slag.

JWS: What equipment do you use to capture images and why?

RP: I work in large format with color slides but also carry a medium format digital camera with me. I found this balance to be fairly pragmatic. Working under a dark cloth on ground glass can be very rewarding if you can endure the burden of it all. It helps me reflect on what I am photographing. There is a sort of privacy under the dark cloth, where I can think about the work and be sort of removed from the place for just a moment to think about just the edges of a frame. But I always have that digital camera should I not be able to set up a tripod and slowly work.

JWS: How do you process your images, and why do you process them the way you do?

RP: It’s hard to describe. I didn’t necessarily come to photography directly. I trained as a painter in school while working fairly interdisciplinary. Because of this I feel fairly comfortable with a wide breadth of working methods.

I no longer paint, nor consider myself a painter. But have at times borrowed from those skills. While working on a series on the high plains of Wyoming, I found it rather challenging to interrupt the place I was working using traditional lens based methods. The photographs I was creating and the videos didn’t resolve the scope of how it felt to experience the wind at night, watching the glow of small towns in the distance. So, I started to make small sketches of the horizon lines, the waves the grass made as they blew, and the subtle lights at night. These drawings became the basis for a series of Chemigrams I would later make. With a few trays laid out in the bathtub of my apartment, I worked to recreate the scenes from these simple little drawings. Folding the paper, dipping fixer, developer, really just playing around with applying the chemicals to create tones and marks which evoked the feelings I could recall from my time on the high plains.

JWS: Beautiful! Why did you choose photography over painting as your medium?

RP: Walking away from the canvas wasn’t easy. But I found myself spending more and more time in my studio and not out on the land. I remember writing this statement about my studio, which turned into a sort of break up letter. I was writing about how much time I was spending creating rectangles inside of this little box, to be hung inside other larger boxes. When what made me want to become an artist in the first place was the connections I made while out on the land.

The camera sort of became the obvious tool for that. I could turn my studio into a backpack which would allow me to spend weeks at a time working, seeing, thinking about the land.

JWS: That makes sense to me. Do you ever experience an overwhelming sense of hopelessness about the subject, and if so, what do you do with that?

RP: Working on Hinterland burdened me emotionally. While working on the project, I continually thought about how we cope with our landscape. How we heat our homes with natural gas to push out the cold of winter but in the same breath of the flame which brings warmth chokes the air. How tenuous our entanglement with the land is.

While working on this project there was a train derailment in the mountain pass just outside of town. It spilled 4300 tons of coal. I wanted to photograph it, and visited it with the intention to photograph it. But, while walking around the folded crushed steel and piles of black rock and dust, I just couldn’t find it within myself to get under the dark cloth. Looking for compositions in this mess was more than I could bear.

Later, I realized how important it is to set aside a space for healing and looking for hope in the land. After working on that project for years, I started looking for part of the land where humans have managed to strike a balance, sometimes through mediation, sometimes through conservation.

Ryan Parker (b. 1989, Twentynine Palms, CA) is a lens based artist and documentarian based in Bozeman, MT. He was raised on military installations across the US and Japan until the age of 13. These early years became integral to the subject matter within Parkers lens based practice. His work is concerned with the altered landscape, specifically the relationship between industrial standardization and economic factors which lead to upheaval in small communities. His large format photographs document the hinterland, the space subtly forgotten.

Parker has exhibited his photographs with the Holter Museum of Art (Helena), the Yellowstone Art Museum (Billings), Usage Gallery (Brooklyn), Praxis Gallery (Minneapolis), The Center for Fine Art Photography (Fort Collins), Atlanta Photography Group (Atlanta), Blue Sky Gallery (Portland), Subjectively Objective (Detroit), Ejecta Projects (Carlisle), and Filter Photo (Chicago). In addition to exhibiting his work, it has been included in publications by Light Leaked, Subjectively Objective, and Pine Island Press. In 2016 he received a Sidney E. Frank Foundation Fellowship, and in 2014 the Edwards Family Endowment for the Arts.

You can learn more about Ryan’s work on his website, https://www.ryanparker.info/ and follow him on Instagram: @ryanparker.studio.

J. Wren Supak is an abstract expressionist who works on paper, digital, or canvas, depending on the project. She has exhibited her work in major cities and events, including Miami’s Art Basel-SCOPE, Budapest Mini Video Art Festival, and Colombia. In photography, she works with captured images from a vehicle, boat, or walk, minimally framed and edited, with found light and color. In painting, she is the opposite; she adds material or pigment and reflects light to the common end of abstraction as a means of explicating ideas.

You can learn more about Wren’s work through her website, http://jwrensupak.com/, and follow her on Instagram: @jwrensupak.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026