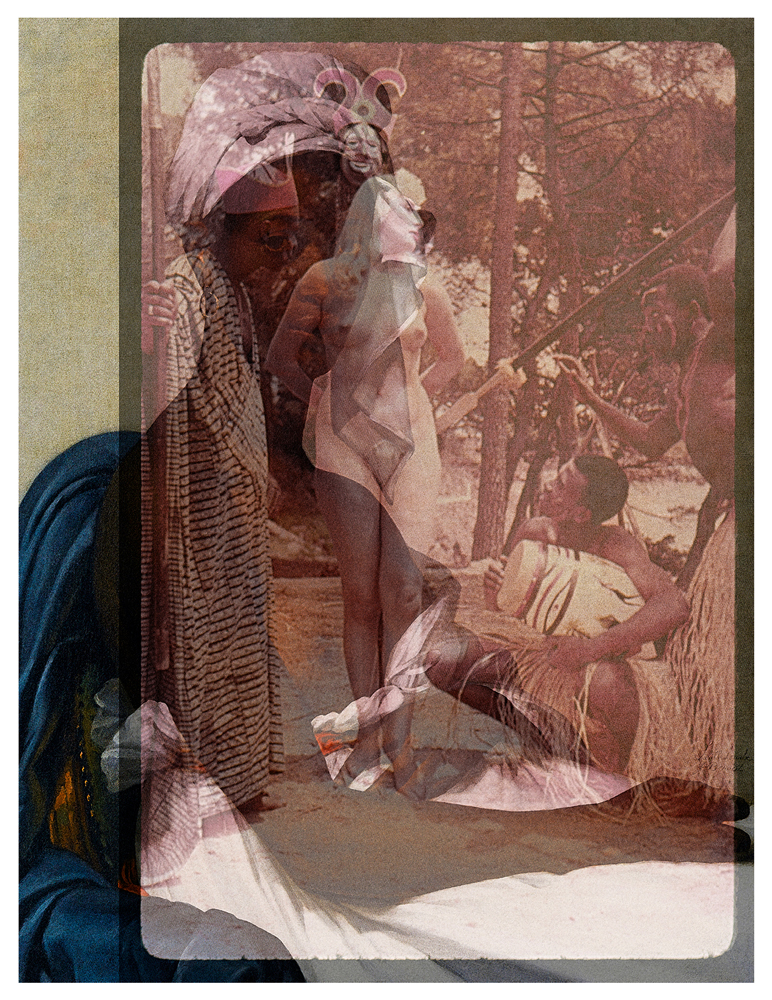

Photography & Anthropology: Gloria Oyarzabal, “USUS FRUCTUS ABUSUS”

Spanish visual artist and photographer. Programmer and co-founder of the independant Cinema “La Enana Marrón” in Madrid (1999-2009) dedicated to the diffusion of auteur, experimental and alternative cinema. She diversifies her professional activity between cinema, photography and teaching.Lives 3 years in Mali (2009-2012) developing her interest and research in the construction of the African imaginary, the processes of colonization/decolonization, the new strategies of colonialism and the diverse voices around African feminisms. Her work is shown, among others, in FOTOFESTIWAL(Lodz,Pl), FORMAT(Derby, UK), ORGAN VIDA(Zagreb, Cr), KaunasFoto (Lith), PHE PhotoEspaña(Madrid, Sp), Athens Photo (Gr), LagosFoto (Nig), Museum of Photography Thessaloniki (Gr), SIPF Singapore International Photo Festival, Photo Marseille(Fr), Odessa Foto Days(Ukr), ARTPHOTOBCN(Bcn), Biennale Für Aktuelle Fotografie (Mannheim, Germany), Helsinki Foto (Fin), Copenhague Photo (Den), FIFBH- Festival Internacional de Belo Horizonte (Br)….

Among her recognitions she has been nominated for the Prix Elysée 2022-2023 and the FOAM Paul Huff Award 2023; and has been awarded with Fotografia Europea 2022, FOTOFESTIWAL LODZ GRAND PRIX 2019(Poland), PHOTOMED 2019 1st Prize, Meitar Award for Excellence in Photography 2019 (Tel Aviv, Israel), Photo Chronicles 2019 Portrait Award, ENCONTROS DA IMAGEM 2018 DISCOVERY AWARD (Braga, Portugal)

She has published two photobooks: PICNOS TSHOMBÉ which received the Landskrona Photobook Award 2017 (Sweden), and WOMAN GO NO’GREE which was awarded with VEVEY IMAGES Photobook Award (Switzerland)and APERTURE PARIS PHOTO Best Photobook of the Year 2020.

Her projects have appeared in several prestigious international publications such as FOAM (Netherlands), M Le Monde (Fr), L’INTERNAZIONALE (It), APERTURE (USA), EXIT(Sp), PAPIERS(Fr), OVER(Irl), BALAM(Arg), THE ART MOMENTUM, THE HUFFINGTON POST(UK),…

Follow on Instagram: @gloria_oyarzabal

If we recognise that it is the artist’s duty to open the eyes/mind of the viewer, and thus raise awareness, then analysis and activism are intrinsic elements: power and responsibility, potential to raise passions, clarify harmful ideological fogs, correct historical errors, generate debate, provoke new thoughts, values and ethics that help to understand and listen.

Assuming the responsibility of those who return home and feed a collective imaginary, sceptical reflections then arise when developing a project, my modus operandi follows alert inputs, and a continuous self-questioning leads me to historical research.

Since my years in Mali, my energies have focused on understanding the Machiavellian and damaging construction of the IDEA of Africa and its imaginary, the complex processes of colonisation/colonisation, the current tactics of neo-colonisation and, almost as a consequence, the wide spectrum of voices in African feminisms. The effect of colonisation and imperialism on the concept of ‘woman’ in other societies and the way gender issues are dealt with thereafter is evident, and the conclusion is that feminist and gender discourses cannot be universalised.

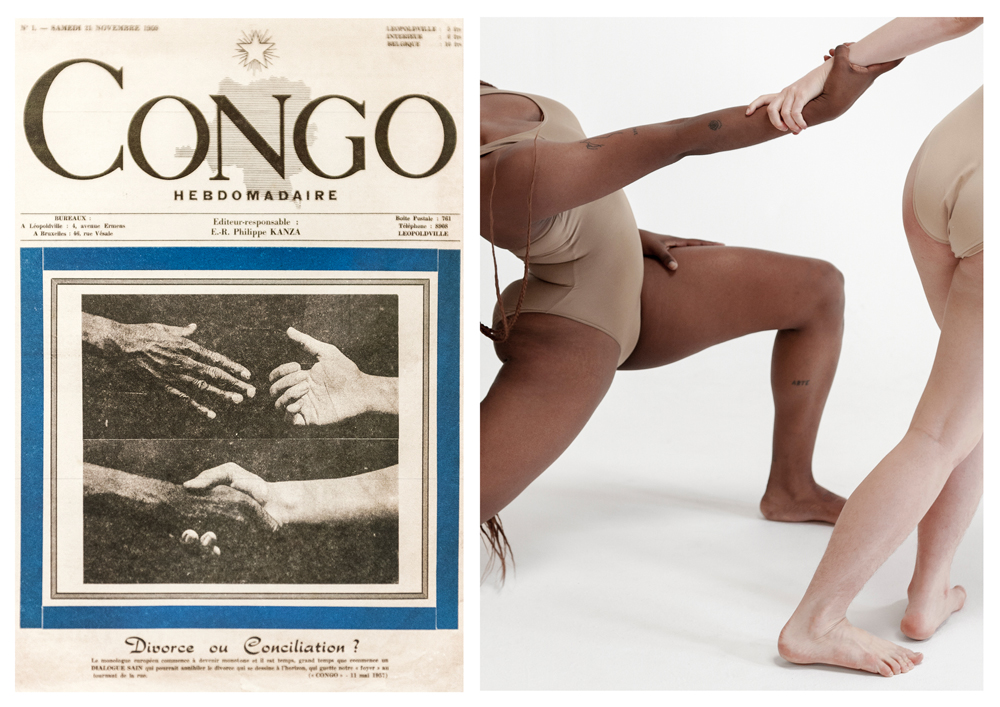

Processes of colonization of the mind: Ngugi wa Thiong’o or Chinua Achebe talk about how European civilization took over the African world and how Western influences through strategies such as language, religion and social structures, changed African societies. Not only geopolitically, but also psychologically, spiritually and mentally.

I research on the creation of the imaginary towards ‘the Other’, based on a perverse exercise of human classification that began, with premeditation and malice aforethought, centuries ago. ‘Gender’ and ‘race’ are social constructions created for the exercise of power: let’s understand how and why patriarchy and racism have come about. I’ve conveyed these ideas by questioning the universalisation of Western feminist discourses, showing how in other communities -e.g., the Yoruba- privilege is not linked to gender.

Museums are not neutral institutions. We walk their corridors in silence, indulging in their beauty, without realising the subliminal narrative that is offered to us. Let’s look behind the curtain and review the representation of the non-white body in Western Art History, offering a parallel narrative that shows another reality diverging from the official one. Let’s listen the voices outside the white box.

Let’s be sceptical, without giving up our illusions.

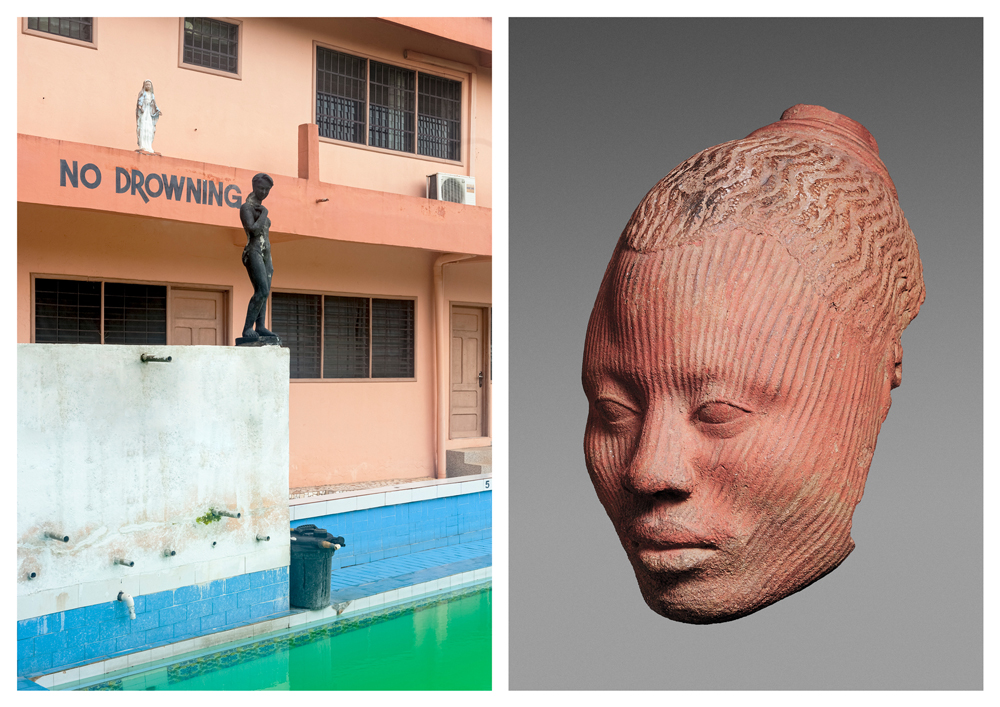

In Roman law, ownership was defined as the absolute full enjoyment over an object or corporeal entity. The USUS was the right that the holder had to make use of the object according to its destination or nature, FRUCTUS was the right to receive the fruits, ABUSUS was the right of disposition based on the power to modify, sell or destroy the object or given entity. Property was perpetual, absolute and exclusive.

Questions of spoliation, hegemonic narratives, race and gender are addressed based on the concept of ownership.

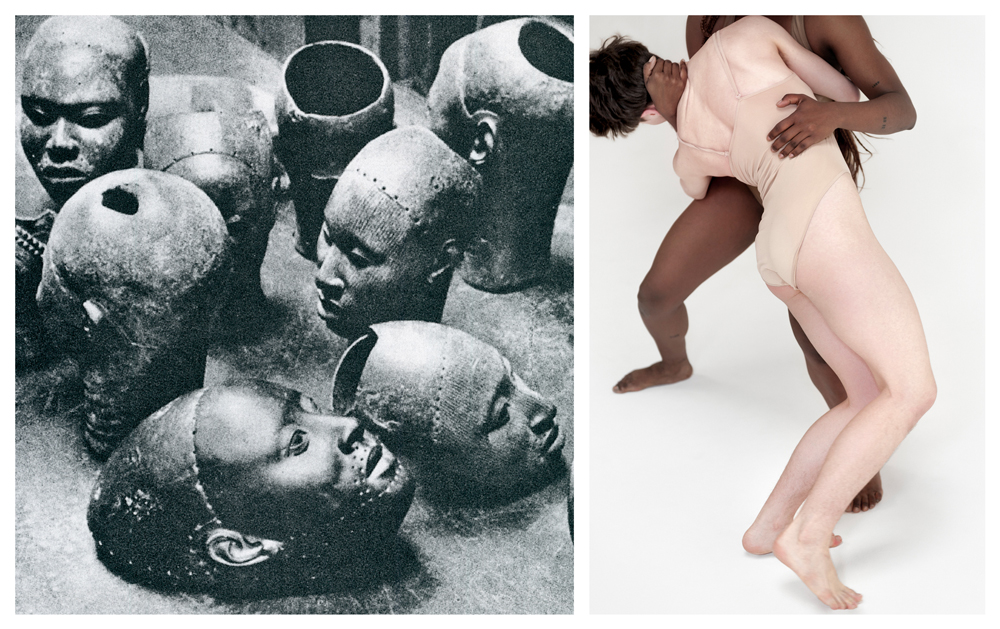

Museums originated as institutions more than 300 years ago, when certain royal collections were made accessible to the great public. They would hence become instrumental tools in the construction of identity and the definition of Nation. And bearing in mind the outstanding colonialist origin of many of their collections, then conflict with History narrative, the creation of knowledge and, consequently, collective and individual memory, becomes unavoidable.

A revision of the relationship between anthropology and museum collections assembled from a despoiling colonial past, its historicity and historiography, justified by a quest for discovery – almost always legitimated through a “rescuing” spirit –, leads to the conclusion that for decades these spaces have reinforced exotism and distinction, intrinsically related to supremacist discourses.

Museums as creators of imaginaries, as institutions that aren’t and have never been neutral holders, yet have benefited from exhibited objects and artefacts. They are a powerful tool for instilling respect, changing prejudices and revising History. Or dangerously the opposite.

Is the concept of museum universal?

Let’s look behind the curtain.

Untie to tie.

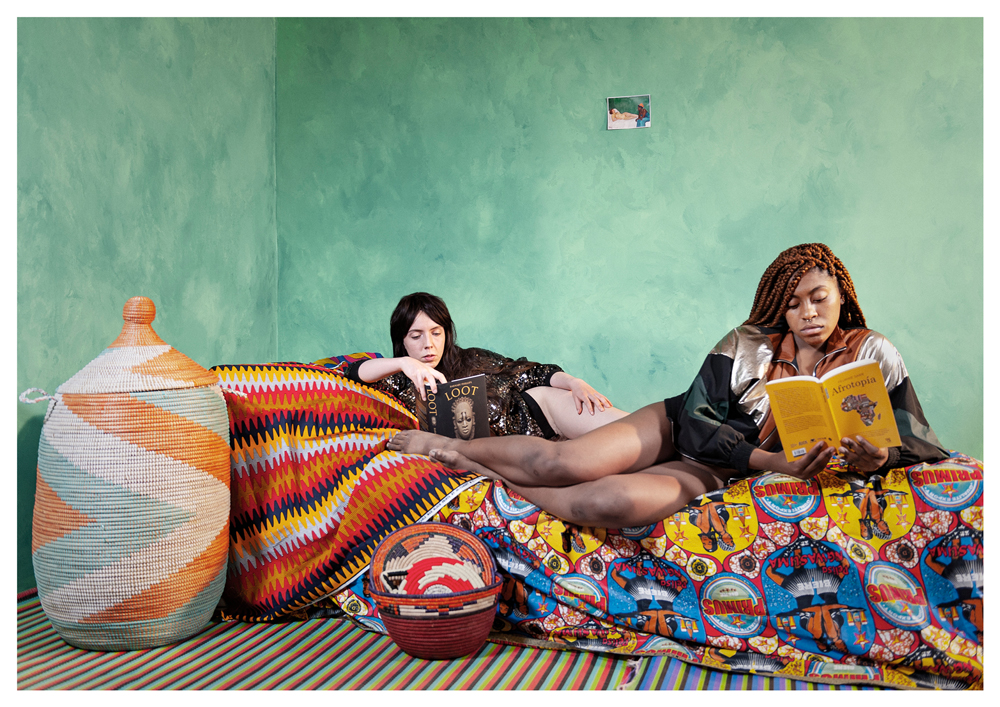

Intrinsically related to ‘otherness’ and linked to the colonisation of the concept of woman, it is pertinent to point out the responsibility of the risky representation of the black woman in the history of Western art. Stereotypes of black sexuality: bold, available and subservient; and also the gaze/position between white women and black women, the relationship of the black woman’s body and identity with the settler that leads to perpetuate stereotypes, reinforce exoticization, allow cultural appropriation, mark out hierarchical differences, etc.…

Eternal Odalisques. Originally, they were female slaves who served in large households -in Muslim community, they were ‘simply’ hard working servants owned by powerful and wealthy households-, but wrongly understood due to the Orientalist school of painting, in which odalisques and other female slaves were often subjects of painterly interest, reinforcing once again a demeaning imaginary. In ´Orientalism´ (1978) Edward Said puts forward a critical concept that describes the way in which the West elaborates a reductionist representation of the Orient, closely linked to the imperialist societies, therefore being an inherently political and power-serving term. As with the Orient, the gaze towards the Other is constructed from the West by a complex process of internalisation of a romanticised version of local culture, explicitly created by the settler powers of the time and all their paraphernalia accompanying it; as, for example, the colonial literature of Joseph Conrad.

Since then, demands have been made for the development of literary theory and cultural criticism, especially in relation to the methodology used by scholars to examine, describe, or explain the ´Other´, generating a large universe such as that of post-colonial studies. One might also consider directing discussions around the book as a cultural critique. [Is the reproduction of archive images responsible of a reinforcement of a stereotypising gaze?]

The odalisque leads to a larger discussion of race within art and art spaces.

Erotic images of women in the geographically vague ‘Orient’ evoke a life of luxury and indolence far removed from 19th century industrial society. This prevails in 21st-century standards of representation of race and gender. How does the colonial endeavour play out across the female body, aesthetically hiding the violence just beneath the surface?

The black female body has long been a distinctive site of transgression and deference to outsiders, especially Europeans. Often reduced to a mere sum of its parts, the extensive records of its oppression are characteristically rooted in a history of slavery, colonial conquest and ethnographic display, creating a collective imaginary based on an overwhelming colonial archive. The mistreatment of the black female body/identity cannot be located in one time period or one offender, but has a particularly long history of scrutiny under Western imaginary as early as the 16th century. In the European context, the black female has been associated with many destructive stereotypes, labelling her as sexually deviant, primitive, subhuman, hyper-sexual, an uncontrollably erotic creature … all under the white gaze. Over time, this same body has been stripped of its autonomy, purged from intellectual spaces and exposed raw as a “bizarre” public spectacle.

And as a starting point my enthrallment with the painting La Blanche et la Noire by the French-Swiss painter Félix Vallotton (1913, Hahnloser Foundation Collection, Winterthur, Switzerland). Inspired by Manet’s Olympia and Ingres’ Odalisque à l’esclave, it depicts the Sapphic love between a sylph and a black woman. Unlike his predecessors, Vallotton dispenses all exotic references.

The familiar reclining nubile female nude of Art History, frozen in time and laid out for voyeuristic pleasure in a post-coital doze, cheeks ruddied from exertion. We assume the gaze, not of the white bourgeois Western male, but a ‘minority ethnic’ woman who is seen to be consuming all the visual pleasures that privileged male archetype feels entitled to. For embedded in this dyad before us is an Orientalist fear and desire for interracial erotic fantasy. Thus, while the western eye bristles at being cast as the black ex- slave, this is tempered by the suggestion of illicit and transgressive relations between the two women.

[But, is my vision being Eurocentric? am I falling into an exercise of victimisation? how to establish a horizontal dialogue? is it essential to collect objects, to exhibit the body? Is restitution a healthy act? Could it have the opposite effect by reinforcing the dependent link with the narrative constructed from power and privilege?]

Starting with a recreation as faithful to the original as possible, then going through different scenarios, it leads to a contemporary reflection in which both women appear reading books as Afrotopia by Felwine Sarr (co-creator with Benedict Savoy of the report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron on the issue of looted objects in French museums, notably the Quai Branly Museum in Paris) or Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes by Barnaby Phillips.

A two-voice dialogue around gender, race and colonialism emerges between them.

Return what has been plundered and looted, both in terms of objects and identity, is it an urgent, universal and feasible question for everyone? Ownership, restitution, reparation, recontextualization… who has agency to give, return, loan, adjudicate, rename?

In order to maintain their economies and symbolic dominance, Western governments expressed fear, wondering whether, in the event of return, African artefacts would be properly maintained and what would be left of their own collections. Many of these museums have appointed themselves as universal guardians of hundreds of thousands of objects which overflow their basements, justifying the greed involved in this with a pathetic paternalistic attitude. This kind of egoistic and supremacist arguments were questioned within the Sarr and Savoy Report, which urged for transparency when it comes to determining the origin of the artifact – whether it was stolen, acquired, or bought during the colonial era – as well as for balance between both continent’s possessions in regards to enhancing their political and cultural relations.

“Things are working out…towards their dazzling conclusions…”

Our Siter Killjoy, 1977

Ama Ata Aidoo

Since I started the project in 2019 and, in part, pushed by the shockwave of Black Lives Matter movement, a significant shift in the positions of museum boards is evident, consequence of pressure exerted by a society that demands and insists on a revision of the narrative. Unfortunately, there is still much reluctance. The best example is the British Museum, which holds around 73,000 African artifacts and which apparently has no intention of restitution.

Over five hundred museums span across the African continent and their voices are still to be heard, but most likely they are no different than the request imposed by the Museum of Black Civilizations (MCN) opened in Dakar, Senegal, in 2018 which archives the history of the Black world and therefore urges for the return of African artifacts held in Western museums. In addition to this demand is the fact that up to 90 percent of the cultural heritage of sub-Saharan Africa is held outside the continent.

The restitution should/could not be just a legal act of returning the stolen artifacts, but an act of reconciliation and recuperation of the previous damage done. The legitimate owners should be entitled to use those objects to reclaim their histories, their voices, and re-integrate them into their communities, and cultures to build a stabile new cultural policy and both internal and external relationships. Or perhaps assess the possibility that certain artefacts may not be possible to return for various reasons. Dialogue, questioning and listening are priorities.

[But, am I being too condescending in considering that restitution “gives them back” something they logically already have (voice, History)? Is this, once again, a Eurocentric mindset? To think that the history of the African continent is only its relationship with ´us´?]

Let’s provoke a polyphonic debate on the function of objects and their role in processes of subjectivation of the individual, as well as in building collective identities. One central concern is the epistemology of the object, which has been created by a distanced Western view on it, as that by anthropologists, art historians or museum curators. These objects are mutants! They have been moved to the Western world and now they have another history; they are incarnating something else. Even if one could elaborate a kind of fantasy of magical power, or “in-betweenness” between the world of the visible and the world of the invisible, trying to come closer to understanding the role they were supposed to play in their original societies, incarnated as divinities, it may be a speculative concept from a position of privilege.

Maybe It’s not about restitution. It’s the debate on restitution. Are these objects watching us and listening to us? They need to be part of this conversation. These objects have to help bring us together around the conversation and make this conversation evolve with the evolution of the whole human society, without distinctions of cultures, genders, social classes, fields of work, etc. Because the “restitution” subject is much more complex than only a North/South legacy, between Africa and the West.

Carlos Barradas: What initially drew you to incorporate anthropological themes into your photography?

Rather than me introducing anthropology into my projects, I think it crept stealthily into them. I was always sceptical towards this discipline of study. I was terrified of approaching this distant and exotic being with the very intention of bringing it closer, of getting to know it. It was all pure macabre irony. Over the years I understood why it didn’t work for me: it was conceived from a hierarchical approach, intrinsically related to supremacist discourses.

Historically, this science is closely linked to mercantile capitalism and the slave trade, to the ‘discoveries’ of new worlds, and was used as a tool within the paraphernalia of colonialism’s voracious extractivism. And still in the 18th century, with the liquidation of slavery and the beginning of colonialism, we find that what was previously differentiated as ‘savage-civilised’ will become ‘primitive-civilised’. Different definition, same intention: theories based on evolution according to Western parameters. Once again universalising our paradigms.

At the beginning, the object of anthropology was the study of non-Western peoples and cultures (indigenous communities, primitive societies, etc.), which was called ‘the cultural other’. And it was in the 1960s that this ‘cultural other’ was defined as different from normality (dominant social sectors), and rurality and what were called ‘subaltern societies’ were studied, generally identified with the marginal, taking the different as ‘unequal’ or ‘inferior’. It was no longer only the distant and exotic, but also included the mentally ill, the peripheral and everything that was not ‘normative’.

Perverse.

And yes, science has also evolved, adapting to a more knowledgeable and plural society. Still, is it relevant today, in the age of the metaverse and cybernetic technology, of AI, to keep talking about the Other?

Then, I mainly realised that anthropology had crept into my reflections, and I had to put myself in front of the mirror and understand why I was replicating these dynamics.

Carlos Barradas: How have your personal or professional experiences significantly influenced your work?

My background comes from Fine Arts, I was an art restorer before I was (officially) a photographer. Studying history, if you like it, is addictive and a great travelling companion.

I am also very much involved in cinema, especially in what is called auteur documentary and experimental cinema. My partner and I created and managed a small cinema in the centre of Madrid for 10 years. Years later I realise that it was a great visual school for me. Everything I was able to retain in my retina has been the basis of my visual language.

When we decided to close the cinema and finish the shooting of the documentary we were developing in Mali, when we settled in with the children, created a home there, and a daily life, I decided to leave the camera for a while to understand why I was replicating images that I didn’t know where they came from. I had become a kind of National Geographic photojournalist photographer type, without asking for it. I was not in my place. Where was all this imagery coming from? I discovered that there was a much more complex narrative around what was troubling me. And I also discovered how the idea of Africa had been constructed more than 500 years ago, with premeditation and malice aforethought.

When I returned to Madrid, I did a Master’s degree at the now defunct Blankpaper School, which changed, enriched and exploded my language and visual thinking. It was a “boom” for me! I opened a Pandora’s box, I entered a complex garden, and ended up questioning and pointing out the tools used for centuries for oppression and the exercise of power.

When I got into that complex garden of dealing with gender and race issues, and being recognised through awards and exhibitions, I could see that these were issues that were not only of interest to me. This encouraged me to go deeper, and above all to ‘sweep the house’: to see how we are still beneficiaries and enjoy even today the consequences of horrible events of the past.

Carlos Barradas: How do you prepare for a new body of work? What kind of research and engagement do you undertake?

I work in parallel with the more historical and scientific part, combining it with the poetic and metaphorical. I need to debate and contrast my arguments and for that you have to have cause and knowledge. But that’s not the only thing that makes an auteur documentary project interesting. What gives it personality is the combination of many factors, and one of them is the ability to generate links between different layers. A story, a poem, a song, a riddle, a quantum formula, a painting, a food, a building, a social movement, a cry …. something that lights up a little light inside you and activates a tension and a mystery.

If the approach is to a community that is not the one I belong to, for me it is very important to research, be aware and listen to the voices of the local, both historically and todays. With attention not to fall into appropriationism, with care and revision of the strategies I use. Acknowledging my privileges.

Carlos Barradas: What ethical considerations do you find most challenging when merging photography with anthropology, and how do you address them?

We must start from the idea that it is difficult to close a definition of what anthropology is, as we find that it is a discipline that is constantly redefining itself. By framing it as a social science whose object of study is difference, the ‘cultural other’, we can dangerously fall into a ‘social Darwinism’, with a comparativist attitude.

Ideally, difference should not imply inferiority but diversity. But as Audre Lorde said, ‘it is not our differences that divide us, but our inability to accept those differences’.

I understood some time ago that we have that responsibility of the one who returns home and reinforces an imaginary, even stereotypes. For me it is a constant struggle with myself not to use difference as a tool of human hierarchies. I live in a constant self-questioning, not forgetting to be an active listener, being able to embrace when malpractice is pointed out to me.

There is also the delicate question of who has agency, and who is responsible for providing it.

Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie talks about “The Danger of the Single Story”:

“…It is impossible to talk about the single story without talking about power. There is a word, an Igbo [a language spoken in Nigeria] word, that I think about whenever I think about the power structures of the world, and it is “nkali.” It’s a noun that loosely translates to “to be greater than another.” Like our economic and political worlds, stories too are defined by the principle of nkali: How they are told, who tells them, when they’re told, how many stories are told, are really dependent on power. Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person.”

Carlos Barradas: In what ways do you negotiate the power dynamics inherent in photographing subjects?

Identifying my privileges and having the subject’s authorization. Participation must be active, without forgetting that the camera gives power.

Carlos Barradas: What impact do you hope your work will have on viewers? Are there specific reactions or discussions you aim to provoke?

I cannot assess the type of impact as they are likely to be very varied. ‘Pointing fingers’ are not always welcome. My dynamic is first to do an exercise of pointing at myself, to put myself in front of the mirror as an exercise of self-analysis. It’s a strategy that gives me kind of confidence, even if it’s hard. If it works for me, I hope it works for the people I question, those who might feel responsible and who know that it is in their power to make small changes in their daily lives and in their environment. I don’t pretend to enlighten anyone; I simply feel like a kind of ‘medium’: I transmit ancestral and contemporary reflections that have to do with improving life in common.

It sounds ideal, but they are small gestures, and we already know that many small gestures….

Yes, I would like to provoke, even if it is a questioning of the hegemonic narrative, to know where this hegemony comes from and to ask yourself on which side of the fence you are.

Carlos Barradas: Can you share any feedback or stories from your work that have been particularly meaningful to you?

When I lived in Mali a couple of times I was told: ‘yes, we blacks are stronger, we withstand the heat better, we have more endurance… but you whites are smarter’.

It seems to me as twisted as the perversion of the narrative can get. Not only have we defined otherness in a hierarchical, dehumanising way, defining the other to determine what we are not and vice versa, but we have managed to universalise this definition.

It is the infinite mirror.

This is not right.

Carlos Barradas: Are there any challenges or areas within anthropological photography that you are interested in exploring further?

Anyone who allows that the approach to another collective, community, group, being, …does not take place on a human scale. That the strange, the exotic can really be transformed into the familiar, starting from a dialogue, with good listening. And the familiar becomes exotic when we talk about our own culture.

More than anthropological photography per se, I would be interested in the dynamics and pitfalls around it.

Finally, I would like to quote Bronislaw Malinowski

‘…to study institutions, customs or codes, or to study man’s behaviour and mentality, without becoming aware of why man lives and in what lies his happiness is, in my opinion, to disdain the greatest reward we can hope to derive from the study of man…’.

Carlos Barradas is a photographer with a Ph.D. in anthropology and a master’s degree in contemporary photography from the Istituto Europeo di Design in Madrid, he has been producing photographic and textual essays on issues such as territory, colonialism and post-colonialism, disability, new masculinities and sustainability. Considered by GUP Magazine as one of the 100 European photography talents (2020). He has already exhibited at Foto Rio, Rencontres d’Arles 2019 & 2023 (promoted by the British Journal of Photography and Der Greif), at the International Center of Photography, in New York (2020) and at the BFoto Festival (2021). Winner of the “Cities in the City” initiative at PhotoEspaña and the Porto Photography Biennale’21, awarded a Criatório (2022) and, more recently, guest artist in residence at Encontros da Imagem 2023 edition. Co-creator and co-editor of the online magazine contemporary photography line SOPA and content editor of the photography platform Lenscratch, based in Los Angeles.

In his work he engages with ambiguity. He positions his photographs in a liminal state, an anthropological concept that refers to an intermediate phase or condition in a certain rite of passage. It intends for them to become a receptacle where people deposit their narratives. In this sense, they become a habitable space, where emotional states, memories and social and cultural values come into play, defining the interpretation made of the image.

His artistic practice is developed around personal work, but also the development of free workshops for the communities he works with, always resulting in fanzines, collective exhibitions or other types of artistic products, as has happened in Portugal, São Tomé and Príncipe or Namibia. He believes that it is through these joint initiatives and the participation of communities that the visual production and the intended local cultural mapping will be richer the greater their engagement.

Follow Carlos Barradas on Instagram: @barradascarlos

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Margo Ovcharenko: OvertimeJanuary 27th, 2026

-

Yumi Janairo Roth: EFFIGY 1462January 20th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025