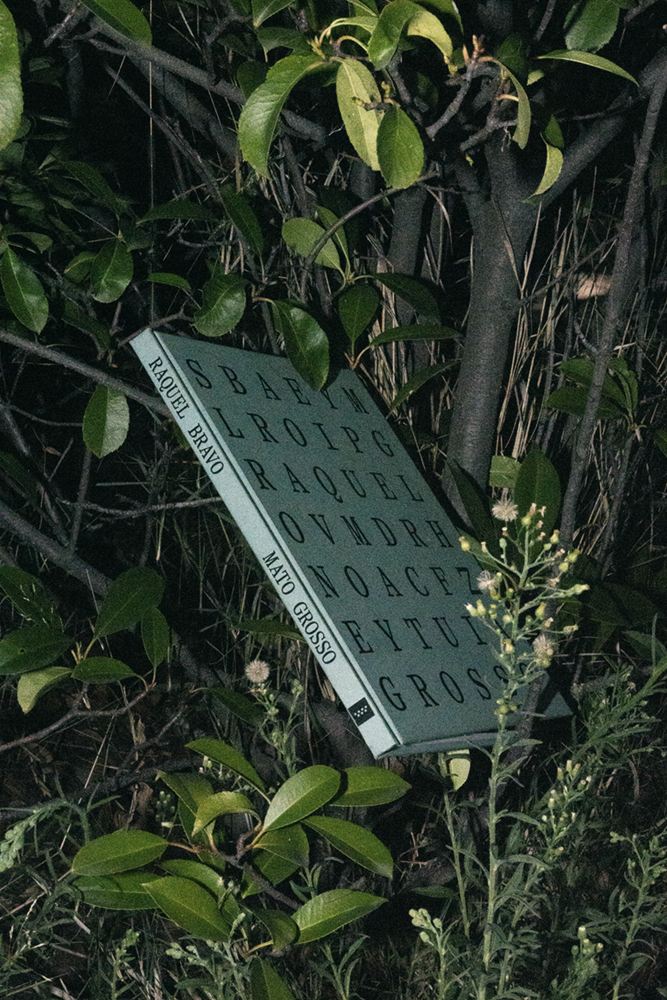

Photography & Anthropology: Raquel Bravo Iglesias, “Mato Grosso”

Raquel Bravo Iglesias is a photographer and educator based in Madrid. Her main concern revolves around memory and intimacy as opportunities for collective negotiation through personal narratives. To this end, she uses archives as a problematic anchor point from which to review the present.

In 2021, her project Mato Grosso won the Fotolibro <40 prize, is published by Fuego Books and is shortlisted for the best book at Les Rencontres de la Photographie d’Arles and Premio Internacional Felifa 2022.

Follow on Instagram: @bravocapitan

As a professor, she currently teaches photography and film studies in Universidad Oberta de Cataluña, Instituto Europeo de Diseño, LENS and CIEE. She is also a tutor at Beca Fuego.

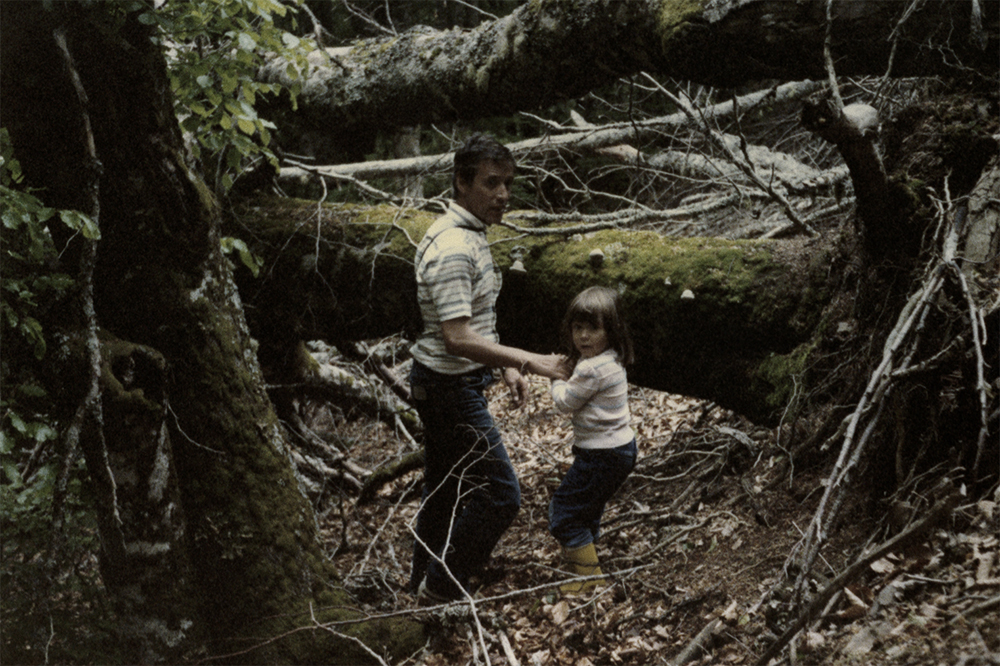

Mato Grosso is a work of post-memory that follows Raquel Bravo’s encounter with the photographic archive of her father Jose Maria Bravo after his death, and the discovery of his missionary action in Brazil that took place before her and her sister’s birth. While the oral account of this experience has been a fundamental part of the author’s childhood, the discrepancies between the photographic images and this account produce a crisis of identity and questioning of remembrance, ritual, and the materials of memory.

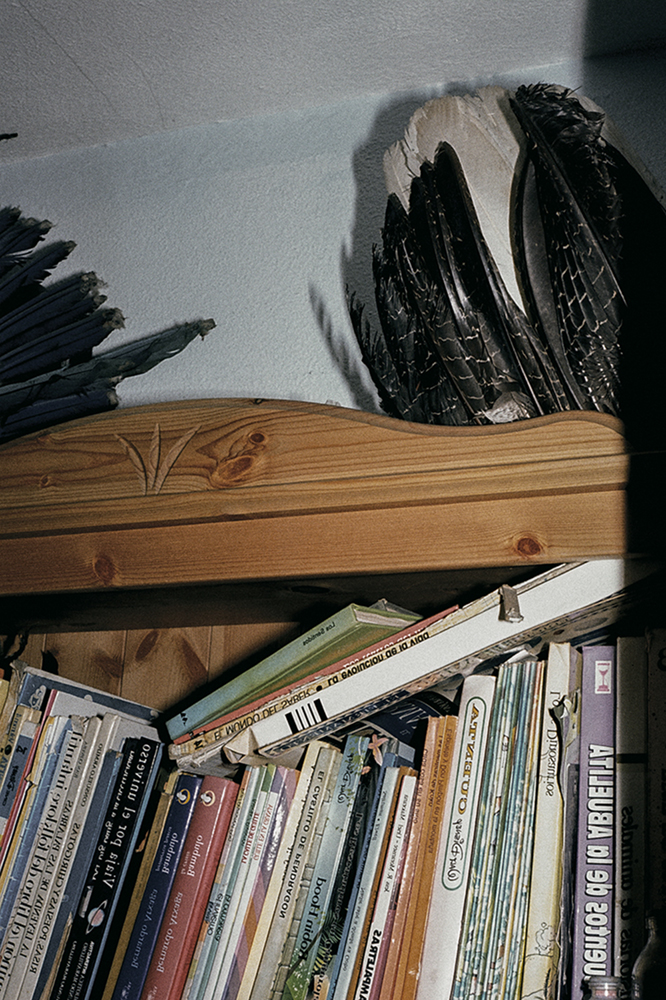

The coexistence of images from the family album edited by her mother Cándida Iglesias with images from the found archive leads to still lifes that act as condensed dramatic stagings. The ensemble of these relationships produces a dialectic that brings into play the foundational fantasies of the author’s family and the type of representation of family albums while revealing unintentional consonances and dissonances with the power structures present in colonialism, capitalism, and the missions of the Catholic Church.

Mato Grosso explores the tensions between personal and collective memory, questioning the historical narrative and its archived representations. Ultimately, the aim is to contribute to critical reflection on the role of the image in the construction of memory and cultural identities.

Carlos Barradas: What initially drew you to incorporate anthropological themes into your photography?

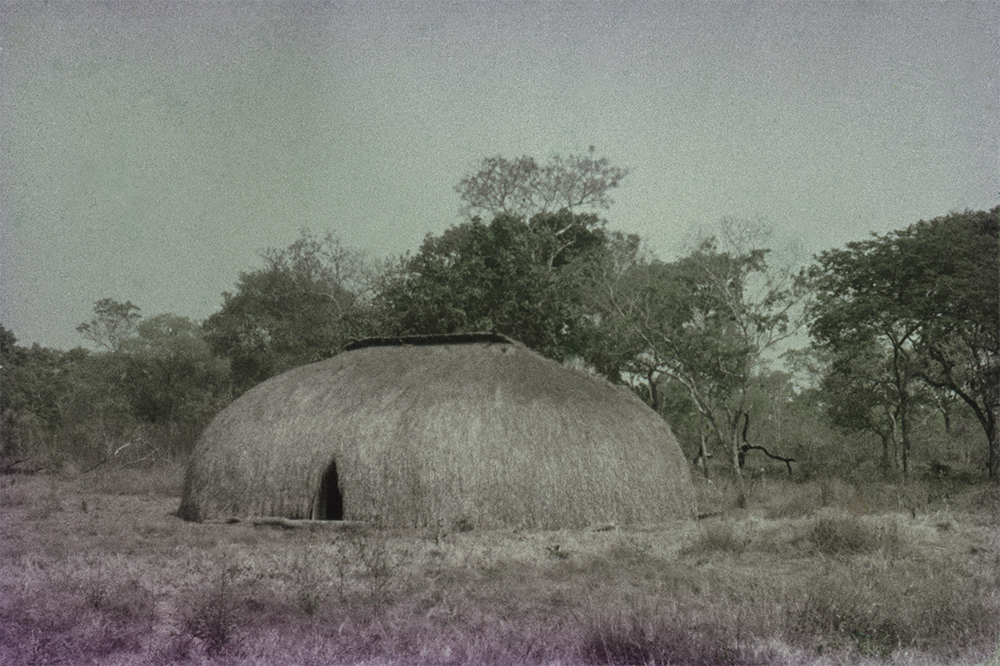

Raquel Bravo Iglesias: The project began with the encounter with a box of slides that my father had taken during the seven years that he had lived among the indigenous communities of the Bororo, Karajá, and Xavante peoples in Mato Grosso, Brazil. My father was not an anthropologist, but the record of his experiences in Brazil draws on the visual conventions and tropes of visual ethnography. The work is a commentary on how we generate different forms and codes of recording when we represent ourselves, as in the family album, and when we represent otherness.

Carlos Barradas: How have your personal or professional experiences significantly influenced your work?

Raquel Bravo Iglesias: My work is interwoven with domestic and family archives linked to my own experience. In this sense, the core of my work is the elaboration and critical engagement with personal memory in relation to collective memory frameworks, such as visual anthropology.

Carlos Barradas: How do you prepare for a new body of work? What kind of research and engagement do you undertake?

Raquel Bravo Iglesias: There is something intuitive in the first steps towards a new project. A doing without expectations and a construction of desire that will drive the most arduous and laborious parts of the work. Later, these first intuitions are brought down to earth through the study and reading of related materials, sometimes also through the compilation of testimonies and formal and theoretical research…

What ethical considerations do you find most challenging when merging photography with anthropology, and how do you address them?

Raquel Bravo Iglesias: First of all, I think it is important to clarify that I am not an anthropologist, but a photographer who has worked with archival material related to anthropology. I am interested in anthropology in a very concrete way, and I am generally a layperson. Visual anthropology has been reflecting on the use of audiovisual recording techniques and their study for more than a century, and there are many critical approaches. These are interesting debates that always tend to leave many open questions rather than strong certainties.

For example, at a given moment, ‘self-representation’ seems to be the panacea for obtaining data that, on the one hand, allows respectful observation and, on the other, can help to generate descriptions from an emic point of view, opening up the interpretive framework and avoiding the biases of the anthropologist. However, it is also overlooked that the recording tool itself (the photographic or video camera) imposes language and representational conventions that are sometimes ‘learned’ or imposed from a false presumption of transparency.

Also, carrying a camera and documenting reality is hard work that sometimes has been required from communities subjected to anthropological research by people with different interests and backgrounds. How do these anthropological studies impact the studied communities? As I document in my book, the colonization and acculturation strategies developed by the Catholic colonies in Mato Grosso in the 1970s came directly from the observations made and published by Levi Strauss on the region’s indigenous communities.

However, this particularity of visual anthropology is part of a broader trend in anthropology itself, which very often shows an unabashed fascination with otherness. In my view, anthropological studies that do not address the distant, the other, and the exotic, but rather turn their tools of analysis towards the local and the near, are still rare but very necessary.

In my specific case, the only way I felt I could legitimately position myself as an author in the face of ethnographic material extracted in a context of acculturation and violence was to expose my own “domestic ethnography” and to speak from the only place where these documents in any way belonged to me: my childhood, during which my father’s oral accounts connected me to Brazil, to the jungle and to the Bororos, Karajás and Xavantes.

Carlos Barradas: What impact do you hope your work will have on viewers? Are there specific reactions or discussions you aim to provoke?

Raquel Bravo Iglesias: I would like to engage in intellectual reflection motivated by some kind of emotional and aesthetic impact. Broadly speaking. In particular, I am interested in raising suspicions about the photographic medium itself and its representational strategies, questioning its transparency, and revealing the mechanisms by which it operates in different contexts. I am also interested in working critically with visual archives and other artifacts. The central question I ask in my work involves a critical look at archives, collections, cupboards, cabinets, and baskets locked and guarded in the back of basements.

Carlos Barradas: In what ways do you negotiate the power dynamics inherent in photographing subjects?

Raquel Bravo Iglesias: Most of the time, I simply don’t photograph people. When I do, I try not to make individual identities visible in the image. If I need a portrait, I always start from a respectful dialogue where I assume that the person should have full power of decision regarding their own image and knowledge of how it will be used. I believe that looking directly into the camera and posing are rights that imply consent, and I do not find candid photography that bypasses these agreements interesting.

Carlos Barradas: Can you share any feedback or stories from your work that have been particularly meaningful to you?

Raquel Bravo Iglesias: I really don’t know what to say. The feedback has been good so far but I can’t think of any special stories other than the usual ones. As my friend and photographer Carlos Alba says, photography is not a field where we get rich or famous. At most, it is a place to share ideas and experiences with interesting people. In this sense, the book has opened the door to many new dialogues.

Carlos Barradas: Are there any challenges or areas within anthropological photography that you are interested in exploring further?

Raquel Bravo Iglesias: Not at the moment, but it is always possible that another project will arise in which it will be necessary to return to visual anthropological approaches.

Carlos Barradas is a photographer with a Ph.D. in anthropology and a master’s degree in contemporary photography from the Istituto Europeo di Design in Madrid, he has been producing photographic and textual essays on issues such as territory, colonialism and post-colonialism, disability, new masculinities and sustainability. Considered by GUP Magazine as one of the 100 European photography talents (2020). He has already exhibited at Foto Rio, Rencontres d’Arles 2019 & 2023 (promoted by the British Journal of Photography and Der Greif), at the International Center of Photography, in New York (2020) and at the BFoto Festival (2021). Winner of the “Cities in the City” initiative at PhotoEspaña and the Porto Photography Biennale’21, awarded a Criatório (2022) and, more recently, guest artist in residence at Encontros da Imagem 2023 edition. Co-creator and co-editor of the online magazine contemporary photography line SOPA and content editor of the photography platform Lenscratch, based in Los Angeles.

In his work he engages with ambiguity. He positions his photographs in a liminal state, an anthropological concept that refers to an intermediate phase or condition in a certain rite of passage. It intends for them to become a receptacle where people deposit their narratives. In this sense, they become a habitable space, where emotional states, memories and social and cultural values come into play, defining the interpretation made of the image.

His artistic practice is developed around personal work, but also the development of free workshops for the communities he works with, always resulting in fanzines, collective exhibitions or other types of artistic products, as has happened in Portugal, São Tomé and Príncipe or Namibia. He believes that it is through these joint initiatives and the participation of communities that the visual production and the intended local cultural mapping will be richer the greater their engagement.

Follow Carlos Barradas on Instagram: @barradascarlos

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Yulia Spiridonova: Wayward SonJanuary 29th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026