David Ellingsen: Days of Plenty: an Archive of Abundance

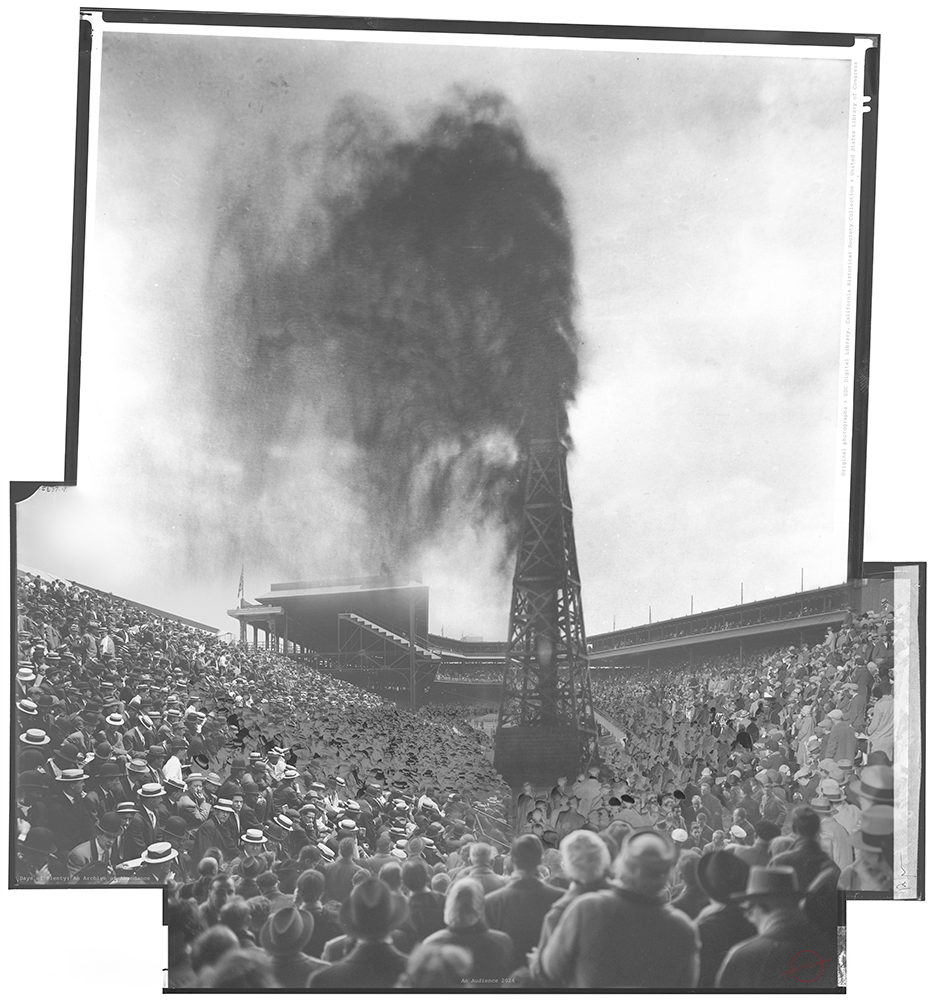

©David Ellingsen, An Audience 2024 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 20×16 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: USC Digital Library in the California Historical Society Collection, United States Library of Congress.

David Ellingsen is a photo-based environmental artist, currently living in Victoria, Canada, who while in his 30s, left a thriving commercial career to return to his roots in British Columbia and pursue an artistic career centered around his family’s legacy of logging on Cortes Island, the

traditional territory of the Klahoose, Tla’amin and Homalco First Nations. Ellingsen’s family settled on Cortes Island in 1887, established the first trading post, and embarked on decades of logging. Ellingsen has spent almost 20 years creating art about the impacts of resource extraction in British Columbia with a keen interest in the relationship between humans and the natural world. He works on long-term projects that challenge us to consider the disastrous impacts of massive resource extraction on climate change and what we can do to mitigate the damage and promote conservation. His practice intersects the documentary and contemporary art worlds with Ellingsen being both observer and participant as he easily shifts between

traditional digital and film formats, constructing images by adding objects or projected images to the scene, which he then photographs.

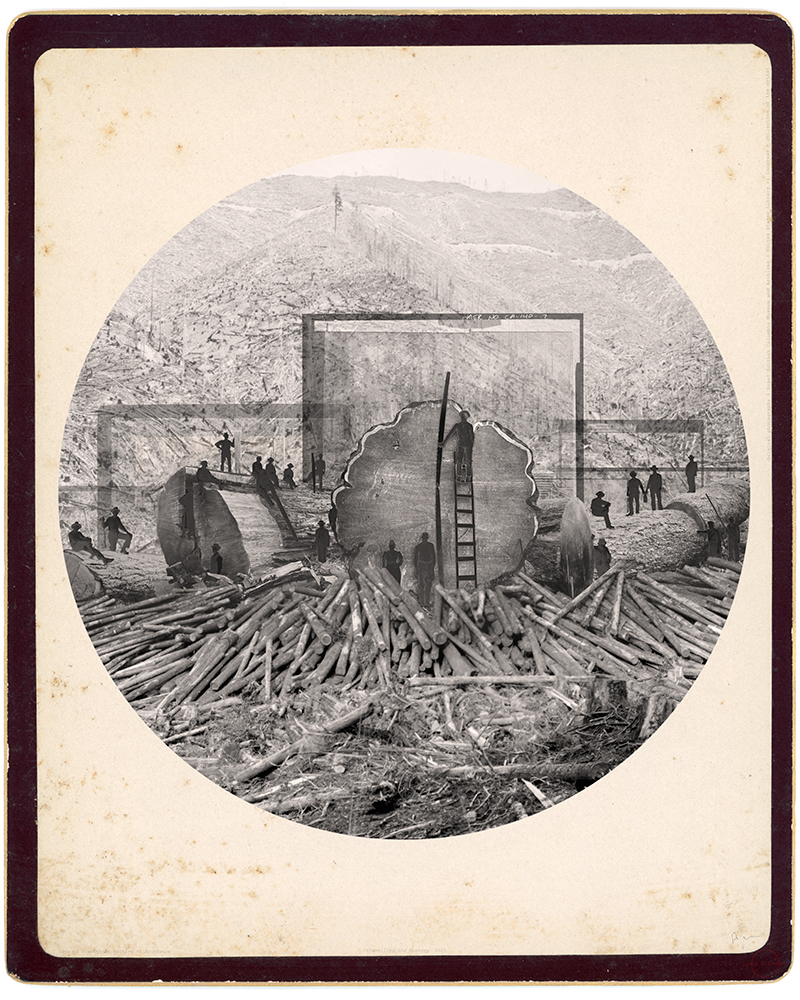

In his latest project, Days of Plenty: An Archive of Abundance, he has shifted to working only with archival images which he scans, combines into one image in Photoshop and digitally prints for exhibition. He also creates 3-D pieces by printing the collage, and mounting the images onto board, which he then hand cuts to shape. He applies gold pigment paint to the edges to mimic gold-leafed cabinet cards. The 3D pieces are pedestal mounted inside a dark frame for exhibition.

Part I of this project was included in Photolucida’s 2023 Critical Mass Top 50, was a Finalist in the LensCulture Art Photography Awards 2024, and received the First Place award at Poland’s Vintage Photo Festival where twelve exhibition prints are currently on view in the Modern Art Gallery at the Leon Wyczółkowski District Museum.

**Michelle Bögre and David Ellingsen met through the CRUX Photography Research Network, an international network of photographic artists, researchers, educators, and theorists who work in a range of genres. Supported by Arts University Bournemouth (AUB), CRUX projects and its members explore key challenges of our time such as climate change, social deprivation, inequality, racism and other forms of discrimination.

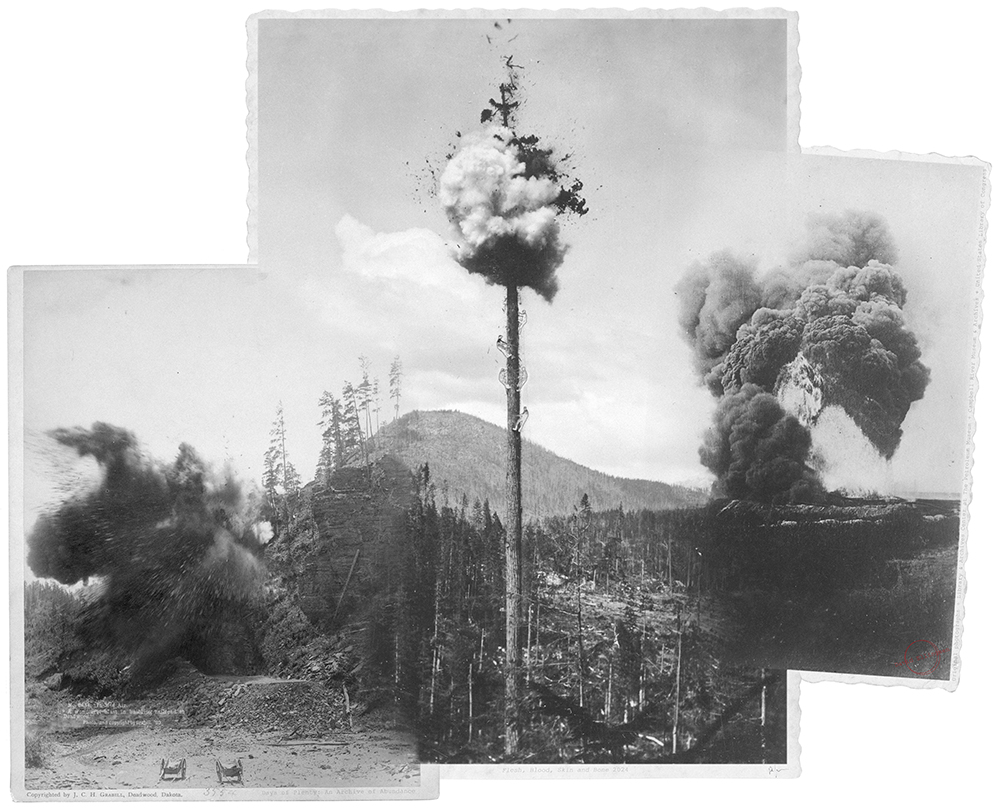

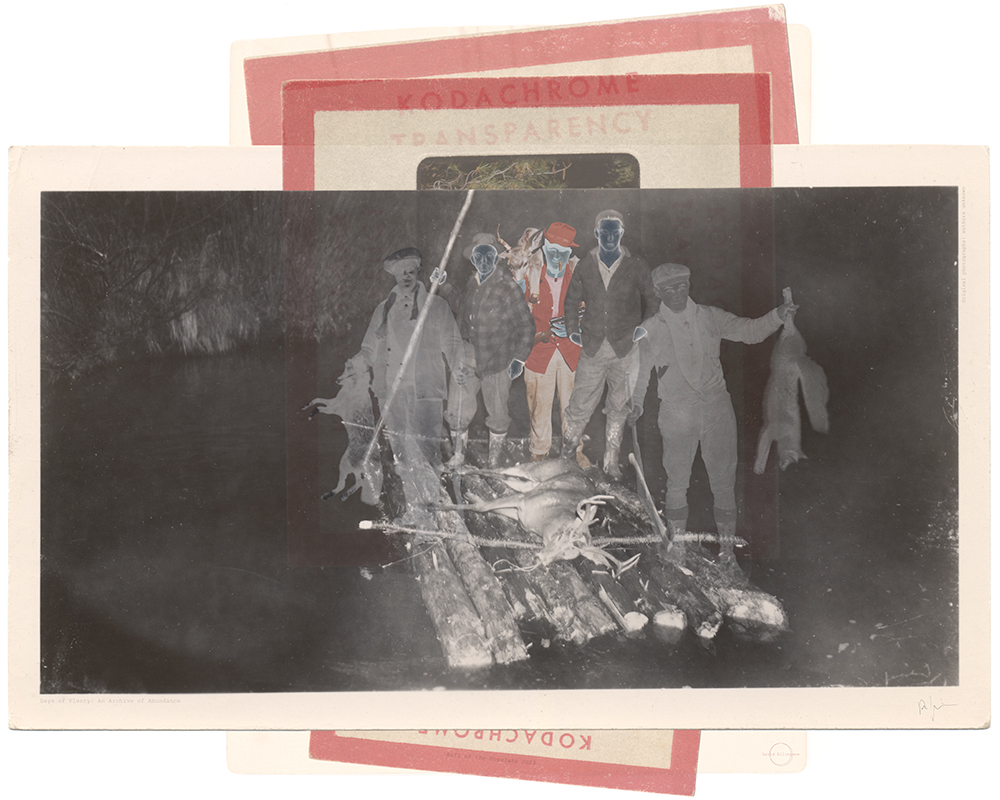

©David Ellingsen, Behold 2024, Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 13×19.5 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

Days of Plenty: an Archive of Abundance

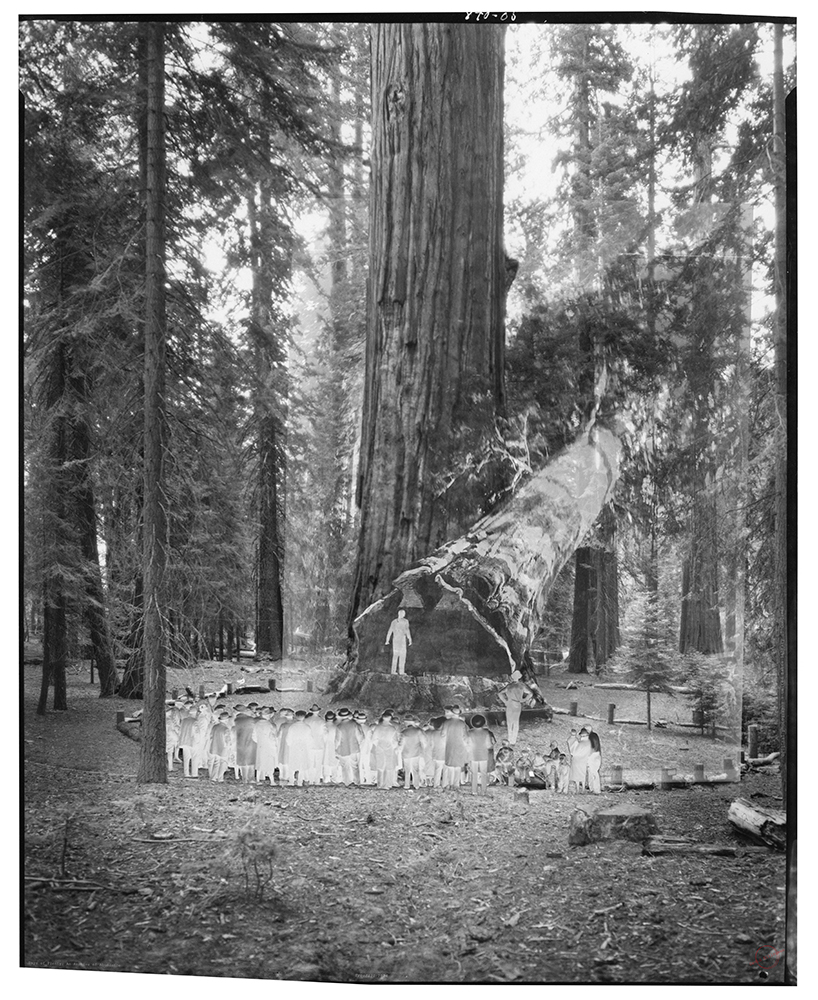

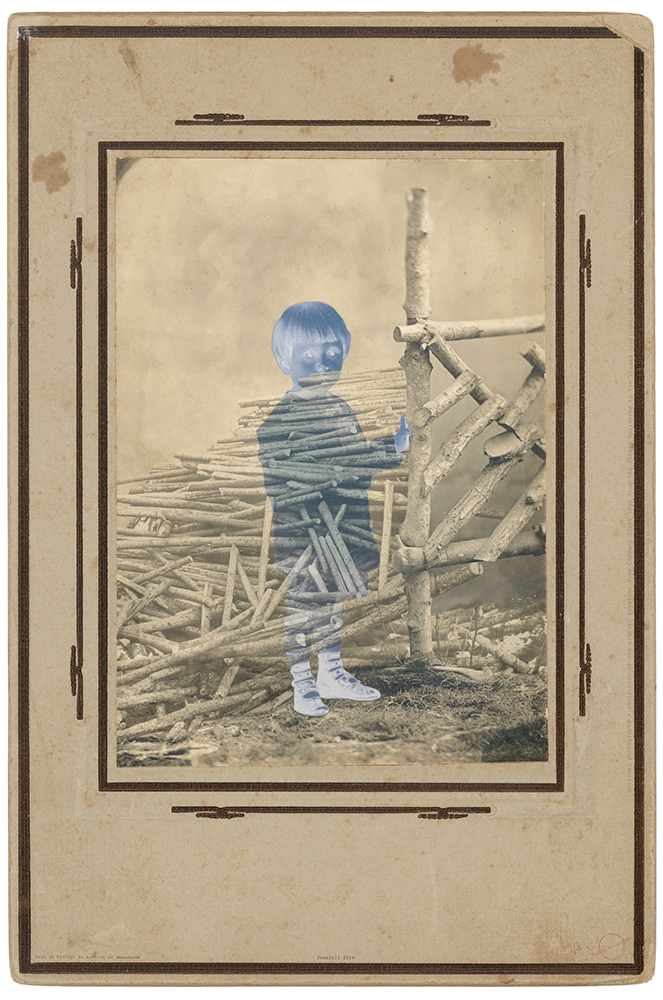

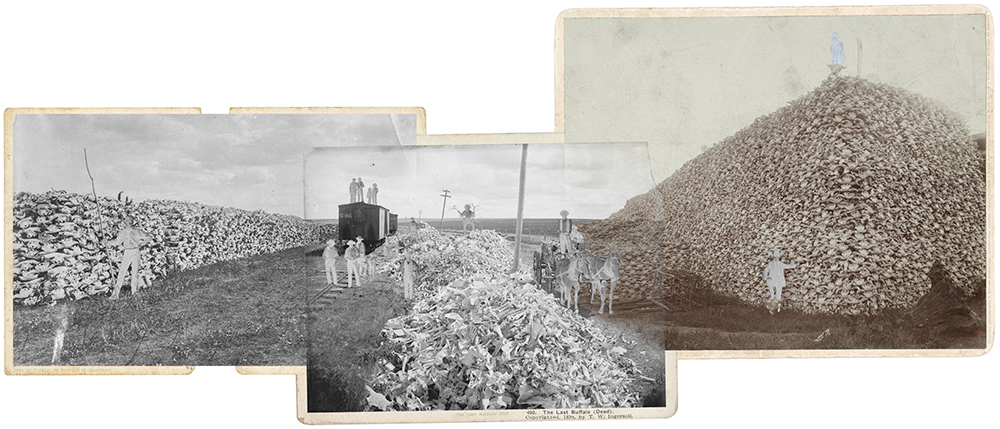

Speaking through a photographic hitory, this project compiles appropriated images into collage works reflecting on human relationship with the living world. At a time when a re-framing of this relationship is urgently called for, these often disturbing works employ extraction as metaphor for the wider story of our attempts of dominion over the natural world. Emerging from my family’s history as colonial settlers working in extractive industries in British Columbia from 1887 through to today, and continuing with photographs collected from around the world, I intend to engage with questions around new paths of relation with the other-than-human.

©David Ellingsen, Unravelling the Mystery, 2023, Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging , 19.5×15.25 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives, United States Library of Congress, collection of the artist.

MB: You’d been spending time in London and other places. Why did you choose to return to, and stay, in Canada close to where you grew up?

DE: As I traveled the world, something kept pulling me back home. With hindsight I eventually realized the inherent value producing place-based work grounded by family history and embedded within the land. In 1887, my ancestors moved to remote Cortes Island, which is about 150 miles north of Victoria, where I live today. They were the first colonial settlers on the island, the first to own land under the pre-emption system, and they established the first trading post with the Indigenous Nations. My family has been involved in the logging industry since that time. While logging continues, British Columbia, like many places, is dealing with the fallout of over a century of heavy industrial deforestation. Revisiting my family’s history from within is a foundation of my photography practice, which looks at the results of colonization and the catastrophic environmental consequences.

©David Ellingsen, Flesh, Blood, Skin & Bone 2024, Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 14.5×18 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Library & Archives Center at The Petroleum Museum, Campbell River Museum & Archives, United States Library of Congress.

MB: Talk about your latest project – Days of Plenty: An Archive of Abundance.

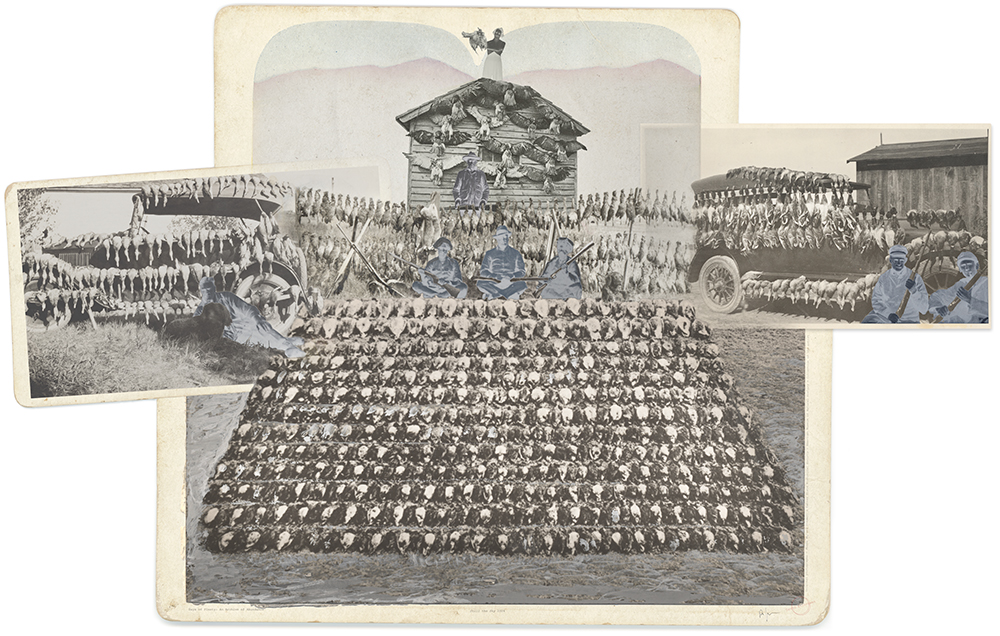

DE: This project-in-progress looks at human relationships with the living world. Both parts look at extraction overall. Part I uses archival images of trophy hunting. Part II (the work shown with this interview) moves into oil, timber and mining, what I regard as the blood, flesh and bones of the land.

©David Ellingsen, Reaping Within 2024 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 12×19.5 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary, United States Library of Congress.

MB: This project marks the first time you’ve worked exclusively with archival images. How did you make that transition?

DE: When I look over my other major projects, I see reflections of the techniques I have employed in Days of Plenty, essentially constructing photographs instead of hunting for them. For instance, in The Last Stand, I would install the old logging tools into the scene and then make the photograph. Its follow up, Falling Boundaries, was the first time I started using archival images, working with the curator at the British Columbia Museum & Archives, finding many striking photographs and combining them with my own original photographs. Techniques like these assist me in telling a deeper story that I also find more visually interesting.

©David Ellingsen, Felling 2024 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging 20×16.5 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Campbell River Museum & Archives, United States Library of Congress

MB: How did you find the archival images for Days of Plenty, because they are not just from Canada?

DE: In a word: time. Hours upon hours combing through hundreds and thousands of photographs. I looked through many of the major archival collections in the world, finding the photographs made as colonialism and capital spread around the globe. Almost without exception the archives, and more importantly their staff, were a dream to work with. The Smithsonian liked the project and donated the photograph of Martha, the last Passenger Pigeon, and the Petroleum Museum in Texas was another standout. As you may imagine I have developed a keen interest in archives and archival photographs.

It’s harder to find current images like these today as corporations have wised up to how this kind of imagery is used, of its power. Often you can’t access these places to photograph anymore. When I shot my photographs for Falling Boundaries, I had to quietly accompany a biologist who was going in to do a study on the old growth trees. I would have been unsuccessful if I had applied as a conservation photographer to get into this area, controlled as it is by the logging company.

©David Ellingsen, Treefall 2024 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging , 20×13 inches . Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Keystone View Company 12260 Logs from the forest delivered to the stream, collection of the artist.

MB: What a massive amount of research. How did you identify all the archives that you wanted to use?

DE: It is a spider’s web that grew organically. As soon as you start to search archives for relevant photographs of extraction, the next thing you know you’re at the Smithsonian, and then the National Library of Austria, and then the Tasmanian Museum, and on and on, not to mention the alternative archive of eBay where I bought a ton of beautiful old photographs.

©David Ellingsen, The Last Buffalo 2023 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 9×20 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library, State Historical Society of North Dakota, Provincial Archives of Alberta.

MB: Tasmania?

DE: All of this was done remotely. It would be wonderful to travel to all these places for this research, but therein lay a rather glaring conflict. I’m conscious of the effects of travel, and I felt it would have tarnished the message of this project. As I could access everything remotely, it meant the travel would have been for my own personal enjoyment which I find increasingly hard to justify if it means further destruction of the natural world. I’m by no means perfect, and I have to live in the world we’ve built for ourselves, but it is important to me that within my work I strive to adhere to the values that I hold in my response to the environmental crisis. I found a quiet joy in being able to do all of this from my studio, collect these most remarkable artifacts of history from all around the world, and speak to the issues of our time. It’s really been quite an experience.

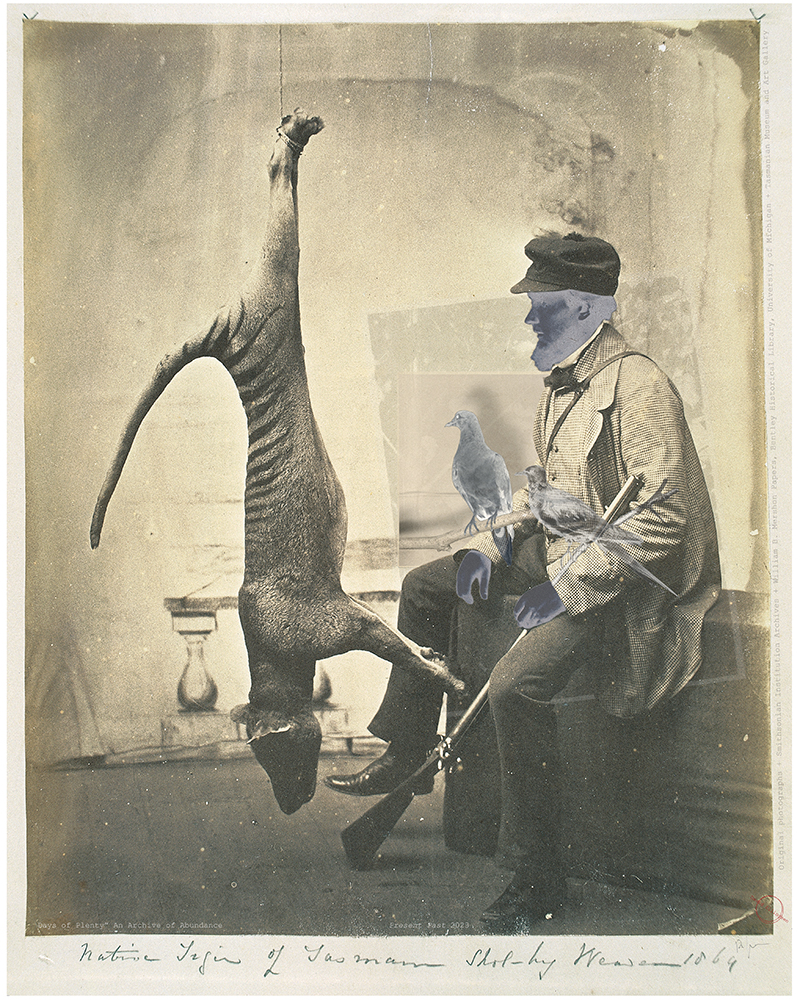

©David Ellingsen, Present Past 2023 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 20×16 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Smithsonian Institution Archives, William B. Mershon Papers in the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

MB: In this latest project almost all of the images are black and white, but you have a few fascinating color photographs. Why add color?

DE: I came across these color lantern slides from the Taylor Family Digital Library at the University of Calgary. I was mesmerized by them because, as with most photographs from this era, I’d been looking at black and white pretty much exclusively. I thought color would be a great addition.

©David Ellingsen, Raft of the Ungulate 2023 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 16×20 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: collection of the artist.

MB: The color from the gas flame is really attractive, even though we know how destructive it is. It’s like Ben Lowy’s images from the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. The images of the oil swirls on the water were gorgeous until you realized that it was an oil slick harming wildlife and polluting the water. So it is beauty, but also the absolute horror of what the damage of fossil fuels have done.

DE: You said the word beauty. I’ve always had this term that I use internally when describing my work – a dark beauty. Maybe there’s something thematically dark, or the rendering employs a darker palette, but it's also beautiful and draws the viewer in. When I’m making my work, I ask myself, “is this darkly beautiful?”

©David Ellingsen, Still the Sky 2023 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 12.5×20 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Musée McCord Stewart, Kansas State Historical Society, American Museum of Natural History, collection of the artist.

MB: How do you generate ideas for the final image? Do you have an idea and then you try tofind the pictures that fit into it, or are you sparked by one of the archival photographs that you find, and that leads to the final piece?

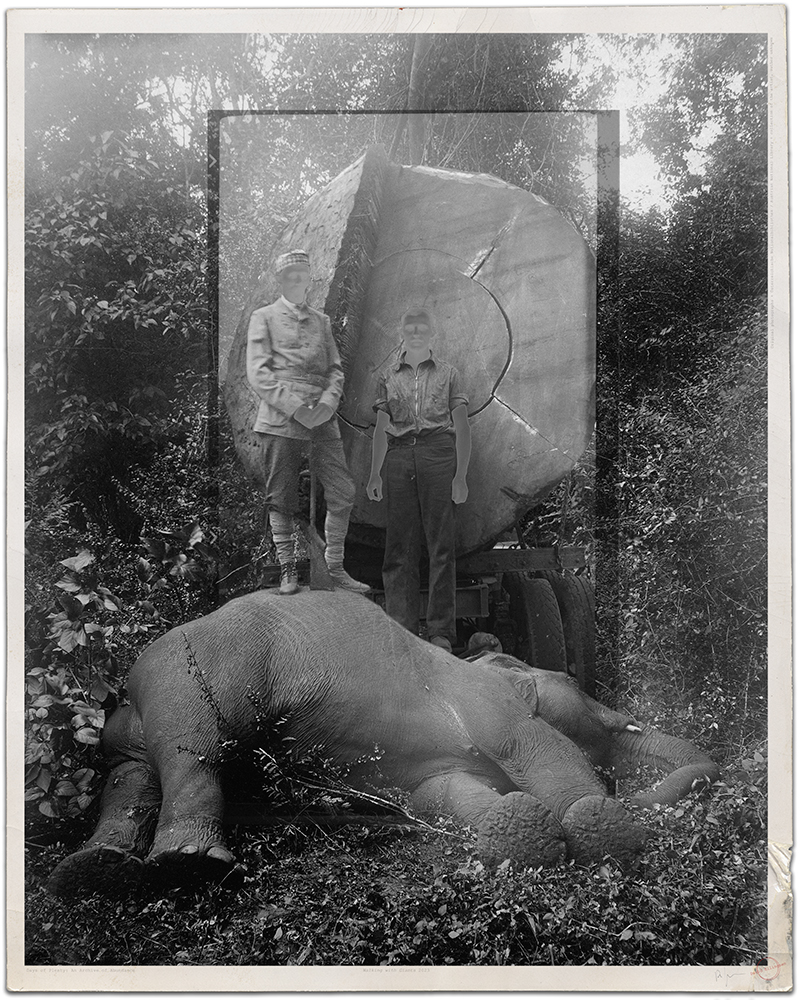

DE: Both happen. Mostly I would say the ideas are sparked by the photos themselves and then taking the time to let them sit with me. I have realized that the more time I have to work on these things, typically the better they are. After I’ve been sitting with the images for a while, an idea of how they’re going to fit together starts to emerge. And then I try out the idea. It takes a long time to make one collage, and some of them have been through 10 iterations. And then sometimes, I’ve taken a piece apart which I thought was complete because I found another photograph that makes it so much stronger, and so I have to rebuild it entirely. Another interesting thing about this project is that I find there’s a power in historical photography that it makes it more accessible. If it were a picture of an elephant that was killed yesterday, people would recoil, perhaps because it’s too immediate. When it’s an historical photograph, with the distance of time, it seems to me that people are more willing to look at it in a deeper way.

©David Ellingsen, A Gathering 2023 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 16×20 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: collection of the artist.

MB: In all the works for this new project you have obscured the faces. Why?

DE: As soon as we see a recognizable face, we focus on it, and I did not want these to be about the individual. It’s a wider story than that. I used the “negative” as a device to assist in this. I also appreciated the historical relevance of the negative to the craft of photography.

©David Ellingsen, Walking With Giants 2023 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 20×16 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Austrian National Library), collection of the artist.

MB: So what would your artist statement about this work be? What do you want viewers to get from it?

DE: At the root, I hope to encourage thoughts toward the other-than-human life on the planet and, to date, the monumental ethical and moral failure of modern civilization in this regard. One needs only a passing acquaintance with current and projected extinction rates to see this is so. There are other ways of living in the world, perhaps unknowable to our human senses, but equal in their own way and no less deserving of the life they possess.

©David Ellingsen, Avian Flew 2023 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 15×20 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions Original photographs: collection of the artist.

MB: Should people be feeling guilty about the past or accept it as something that was done before we understood the consequences?

DE: Humans are amazing creatures who can do wonderful things, but I think we also must look clearly at our history of destruction—face it, absorb it, feel it—before we can start to make real progress. Modelled by many Indigenous cultures, we must re-incorporate a true reverence for the other-than-human into all decisions going forward.

MB: For you, what is the ideal impact of this work?

DE:. I think every artist has some idea, however deep inside it is, of what they would like their work to do out in the world. If even one person changes something in their life that makes things better down the line, then I consider that to be a success.

©David Ellingsen, Wild Men Who Catch and Sing 2024 Digital collage. Pigment ink on cotton rag paper, mounted and hand-cut to shape, with gold edging, 10.5×20 inches. Exhibition prints: pigment ink on cotton rag. Variable dimensions. Original photographs: Die März-Revolten Berlin Bundesarchiv, collection of the artist.

David Ellingsen is a Canadian photo-based artist working through long-term projects focusing on forests, biodiversity and climate. His work draws upon a colonial family history, one often embedded within British Columbia’s troubled forest industry, and reflects on the impacts of resource extraction and consumption on past, present, and future eco-systems. Exhibitions include China’s Lishui Museum of Art, the San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art, Lithuania’s Kaunas Photo Festival and Canada’s Campbell River and Beaty Biodiversity Museums.

https://www.instagram.com/davidellingsenphoto/

Michelle Bogre is an educator, copyright lawyer, documentary photographer and author of four books, Photography As Activism: Images for Social Change, second edition (coming out Fall 2024), Photography 4.0: A Teaching Guide for the 21st Century, Documentary Photography Reconsidered: History, Theory and Practice, and The Routledge Companion to Copyright and Creativity in the 21st Century. She currently holds the title of Professor Emerita from Parsons School of Design, after a 25-year career that included being Chair of the Photo department, and teaching almost every type of photography class. She is also the co-founder of the CRUX Photography Research Network, an international network of artists, researchers, educators and theorists who engage in making work that makes a difference. She regularly writes and lectures about copyright and photography.

Instagram: @michellebogre

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025