Leah Sobsey and Amanda Marchand: This Earthen Door

A statement by the artists on THIS EARTHEN DOOR:

Since 2020, Leah Sobsey and I, Amanda Marchand, have been collaborating on the making of “This Earthen Door,” a work documenting our encounter with poet Emily Dickinson’s herbarium. Published, largely, only after her death, the iconic 19th-century poet was better known as a gardener during her lifetime. Over one-third of her poems and half her letters reference flowers and plants, illuminating her deep connection to the natural world.

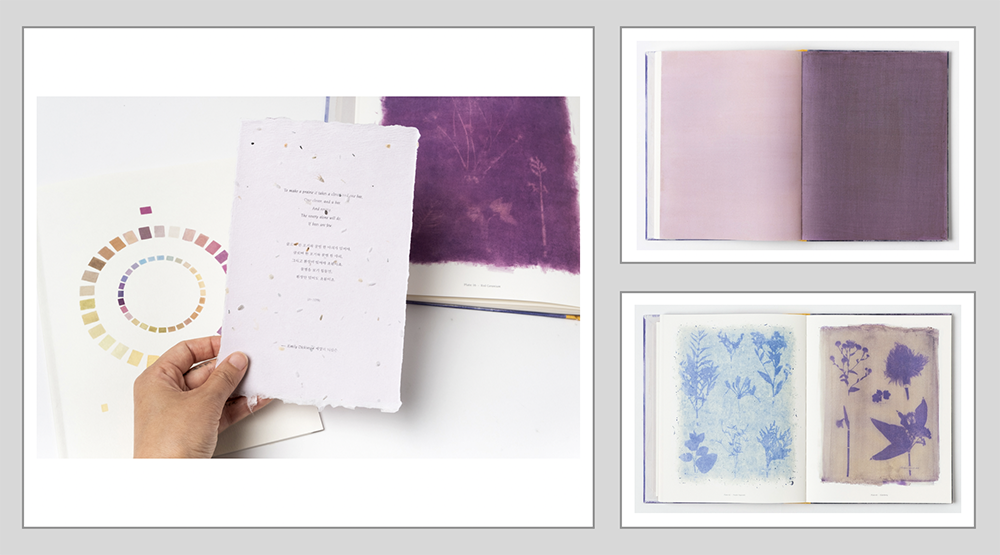

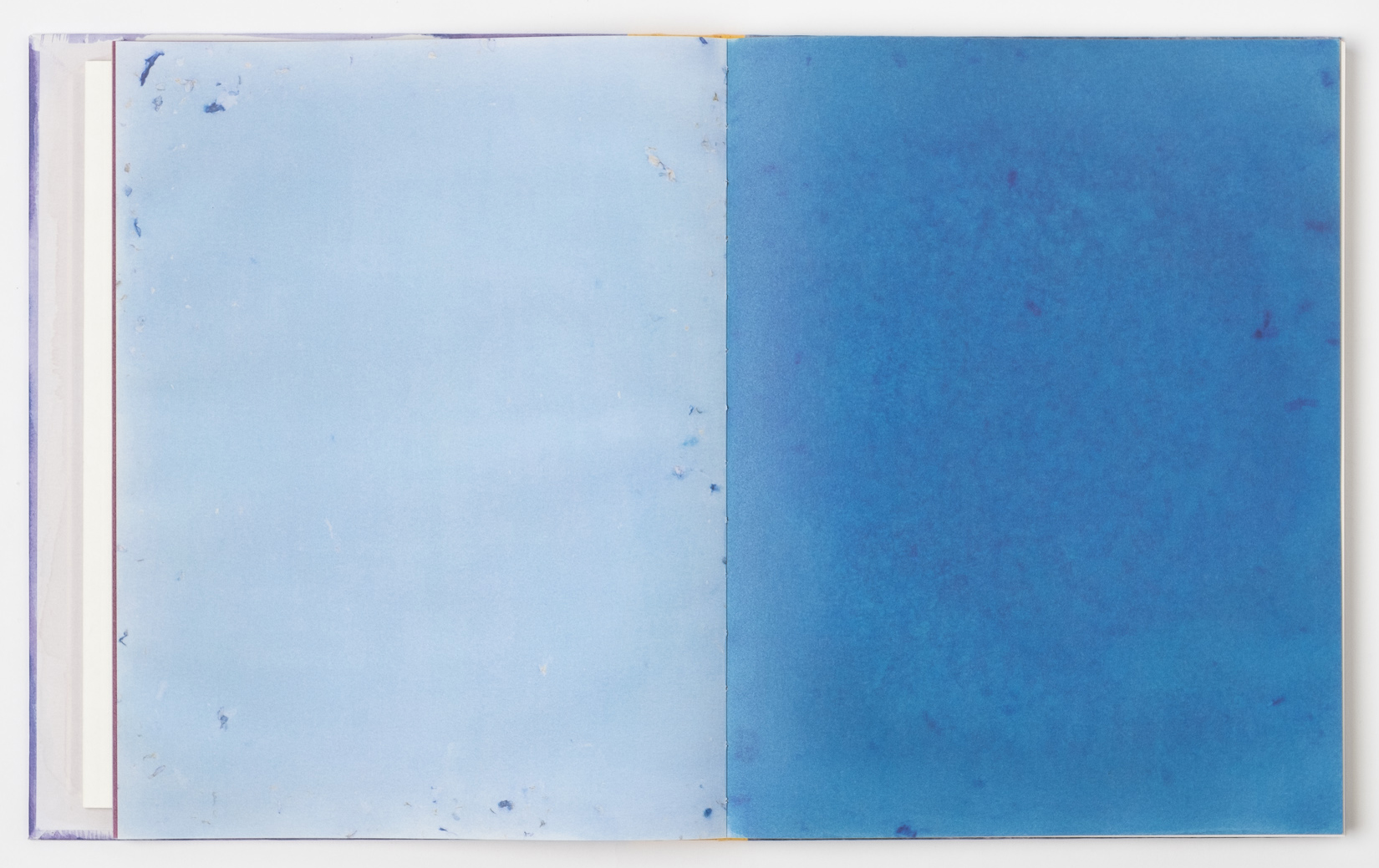

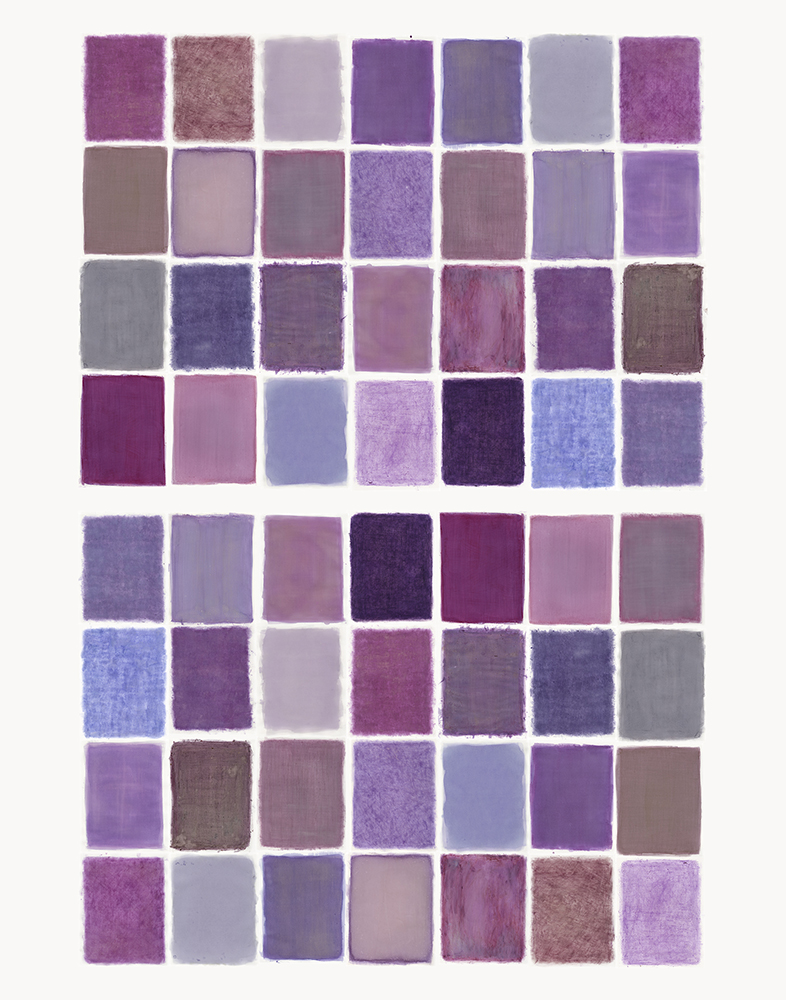

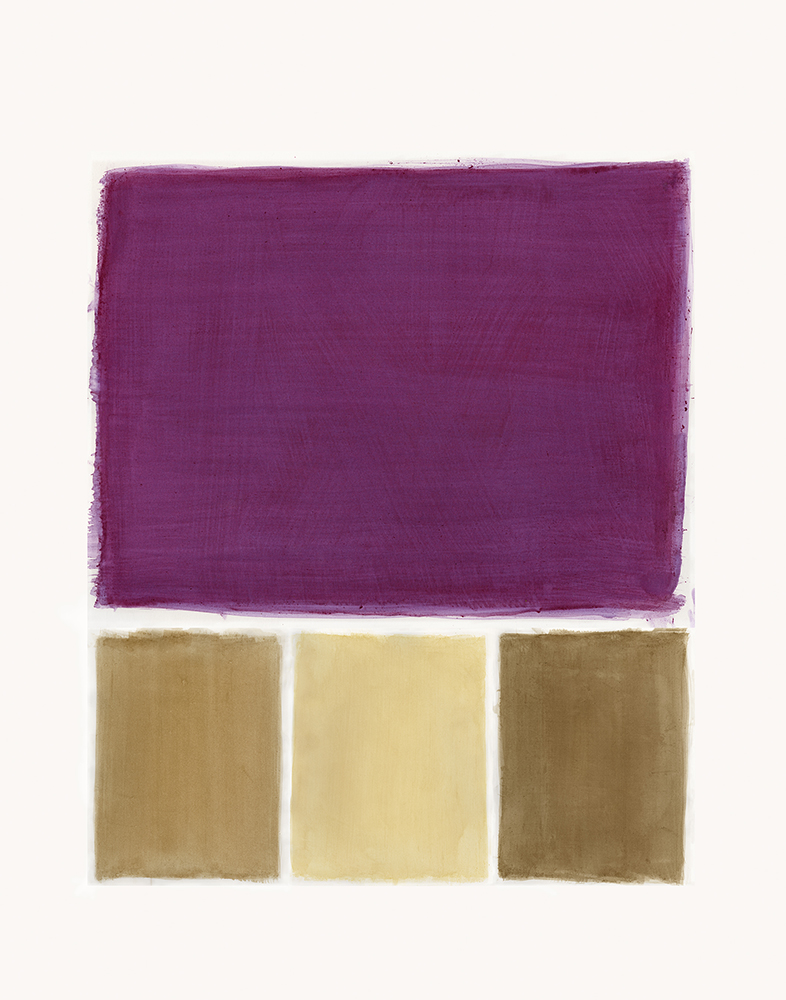

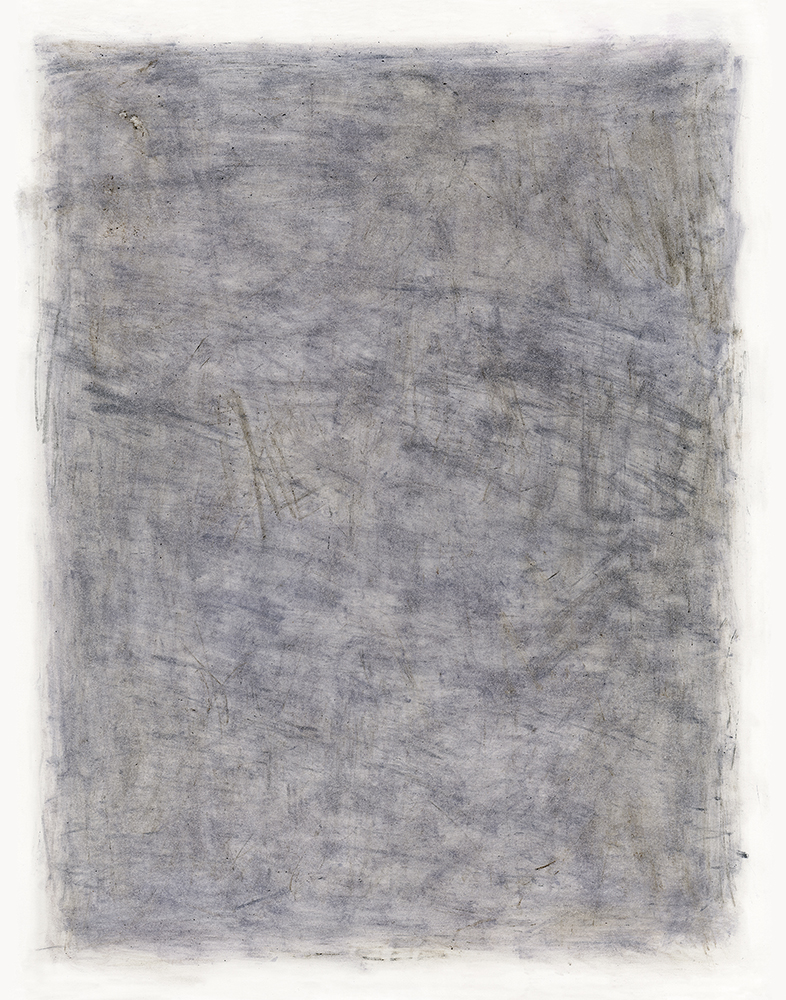

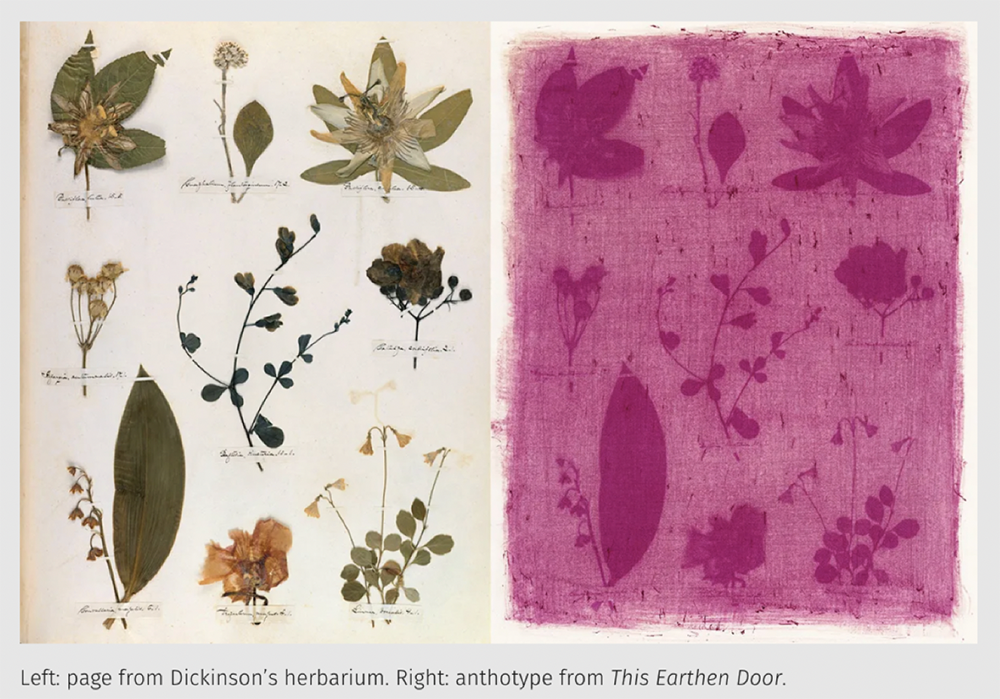

In a gesture honoring her nearly 200-year-old effort, we grew and harvested plants to remake her flower-sampler with an alternative photo process known as anthotype. “Antho” means flower in Greek. Anthotypes are plant-based photographs, an innovation dating back to when Dickinson was at work on her herbarium. This eco-feminist collaboration provides a portal through which we examine our changing environment today.

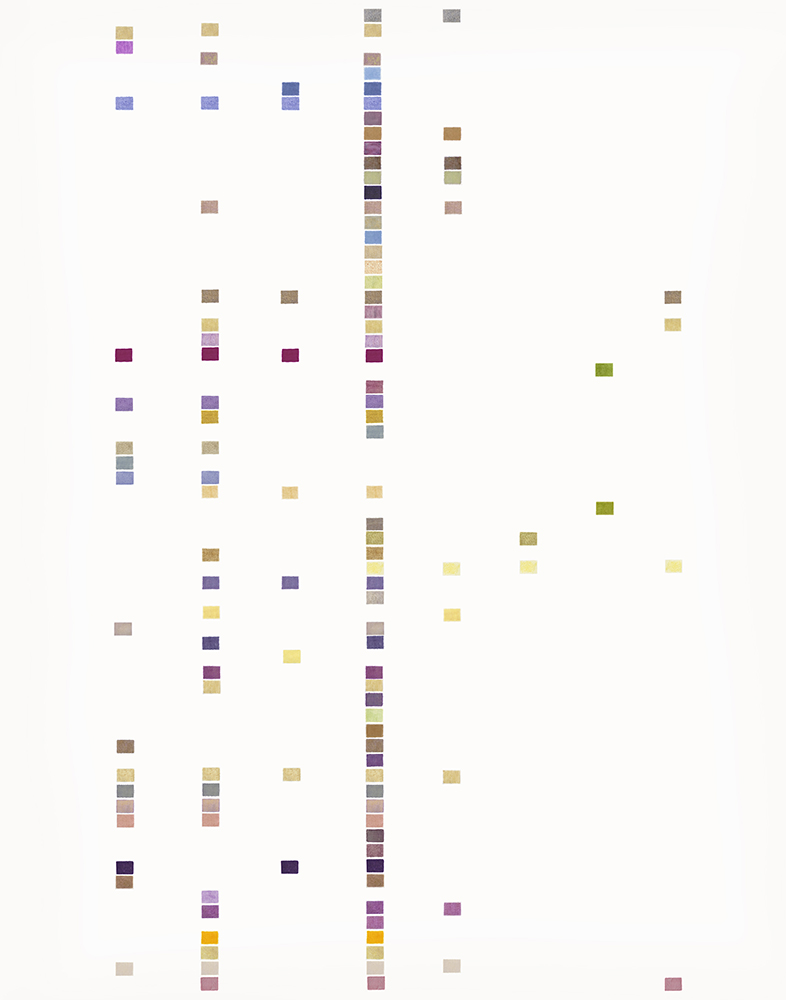

We partnered with two scientists: Dr. Kyra Krakos, a professor of biology; and Peter Grima, botanist and Dickinson herbarium scholar. “This Earthen Door” is a two-part work: in conversation with scientists and Dickinson scholars, it is forging a necessary conversation between art and ecology. Part I, HERBARIUM, reanimates Emily Dickinson’s original herbarium in shimmering plant hues. Part II, CHROMOTAXIA, is our “research project,” including 33 science-based data-drawings that address climate, botany, and ecologically focused stories about the gardener-poet.

What valuable information can be excavated from this 200-year-old nearly forgotten archive? This Earthen Door gives a glimpse into the nature-inspired world of the enigmatic poet and asks where she might point us in this moment of “plant invisibility” and climate chaos.

©Leah Sobsey and Amanda Marchand, Emily Dickinson Herbarium page (left), This Earthen Door: Herbarium Plate 9 -Pokeweed (right)

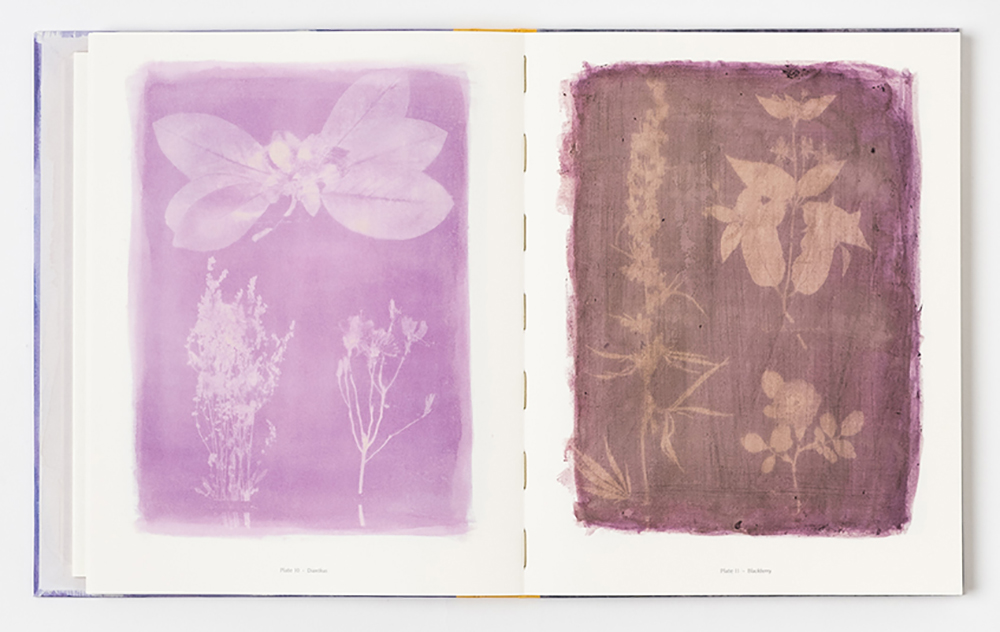

©Leah Sobsey and Amanda Marchand, Herbarium Plate 10 – Dianthus (left) Herbarium Plate 11 – Blackberry (right)

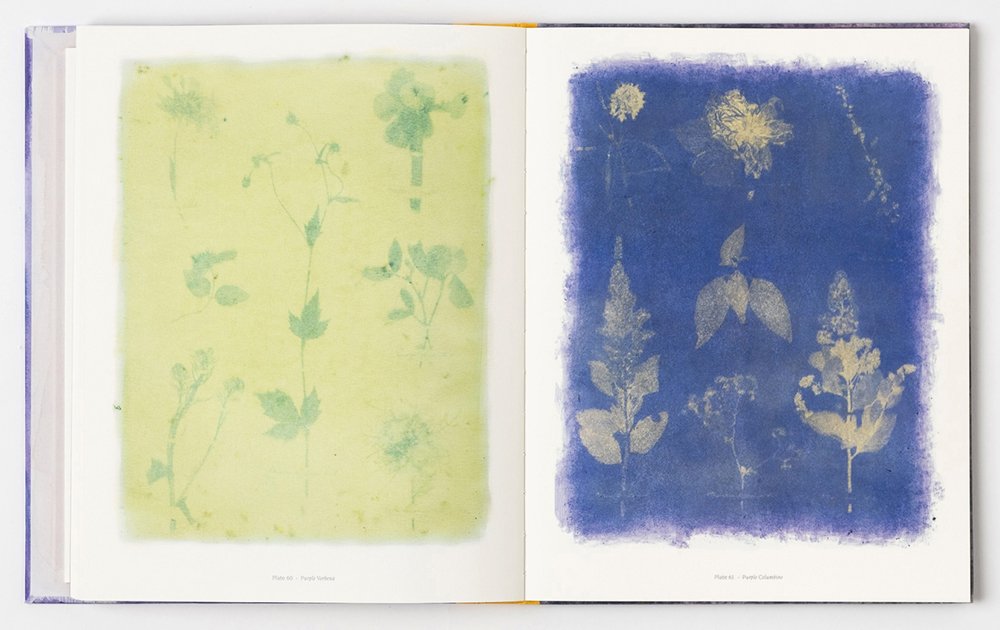

©Leah Sobsey and Amanda Marchand, Herbarium Plate 61 – Purple Verbena (left) Herbarium Plate 63 – Purple Columbine (right)

Leah: How did you form your collaboration and arrive at Emily Dickinson as your subject?

Amanda: Leah and I have known each other since our grad school days at the San Francisco Art Institute in the early 2000s. After graduation, Leah moved to North Carolina, and I moved to Brooklyn, and during one visit we talked about collaborating. At the start of the pandemic, Leah was taking an experimental photography class at Harvard and suggested I take it too – an online, plant-based photo class with educator, Anne Eder. This dovetailed with our mutual interests in experimental photography and the natural world and reignited the conversation about collaborating. We knew that we wanted to work with the natural world and feminism, and very quickly, in a matter of minutes, really, we had decided to work with Emily Dickinson’s herbarium, a book of pressed plants the poet made as a teenager – in fact, her first book.

Emily’s book of flowers was an object we had both become aware of. We quietly coveted it. We were drawn to its tenderly arranged, metered pages of 424 plant specimens, delicately pressed and preserved, inked with her handwritten labels. It had left an indelible mark on us. In a prior collaboration, Leah had been working with Henri David Thoreau’s herbarium, another famous herbarium, though a very different one. Both of us had been working on projects centered on disappearing species – Leah with Thoreau’s specimens through cyanotypes, and I with endangered birds, ferns, and wildflowers through lumen printing. Both of us approach photography experimentally, so the Dickinson’s herbarium was a perfect intersection for us. Essentially, we wished we could own her book of flowers, hold it in our hands, but we knew we never could. It lives in a temperature-controlled vault at Harvard’s Houghton Library, and its delicate pages crumble if handled. It is completely off limits – for eternity. So, we decided to make it for ourselves – and the world.

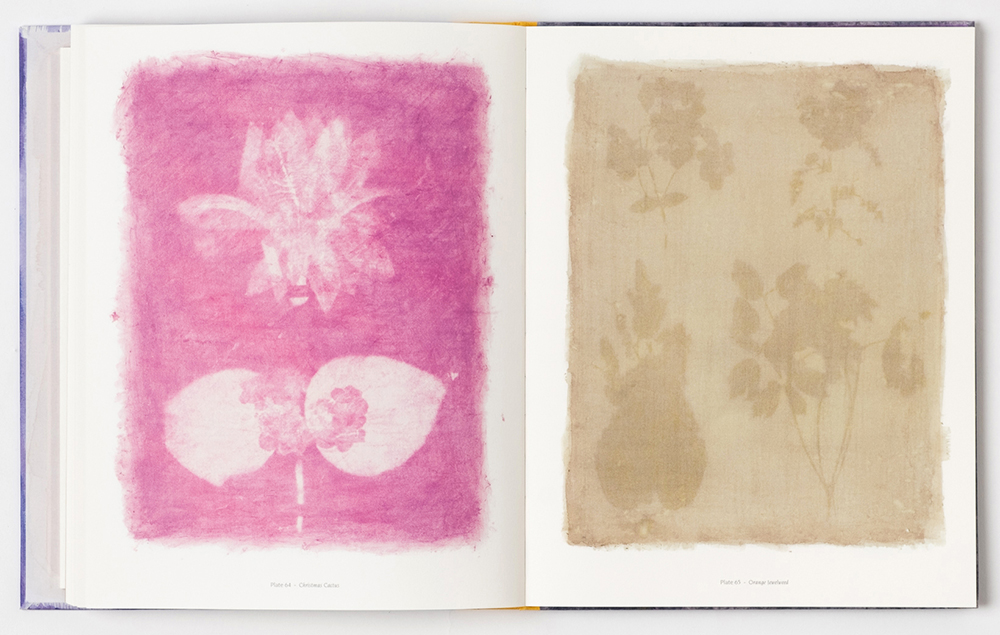

©Leah Sobsey and Amanda Marchand, Herbarium Plate 64 – Christmas Cactus (left) Herbarium Plate 65 – Orange Jewelweed (right)

Amanda: Why anthotypes for this project?

Leah: During her lifetime, Emily Dickinson was known for her green thumb – for being able to rescue any forsaken plant. It was no secret that she wrote poetry, but she was known about town for her glorious garden and for gifting small bouquets, called nosegays, with some writing or a poem tucked inside. She began tending the family garden at the age of 12, and later studied botany at Mount Holyoke University. Over one-third of her poems and half her letters reference flowers and plants, illuminating her deep connection to the natural world. Anthotypes are plant-based photographs, an innovation dating back to when Dickinson was at work on her herbarium in the 1840s. Antho is from the Greek word flower. This experimental photo process, that uses the pigments of plants and flowers to reanimate her book’s pages, speaks to her passion for flowers and love of the natural world, and her slow, careful study of it.

Historically, the invention of anthotypes was an attempt to invent color photography. Our project is also a color taxonomy of sorts. Dickinson shows a true fascination with color in her writing. Common and exotic colors—blue vs. azure—appear often in her poetry and letters. Shades of gold (golden, gilded), or scarlet (ruddy, crimson, brick) are most widely used, along with favored color purple. Our deep dive into the pool of natural plant color is an ode to both the poet with her color words and garden, and to nature and its many stunning, non-synthetic hues.

Leah: How has collaborating with scientists changed or grown the project?

Amanda: Initially we set out to re-animate Dickinson’s book of pressed plants, but the subject was richer and more nuanced than we had originally gleaned. It took two years (and then some) of collaborative research and making to produce her 66-page book as anthotypes. While researching Dickinson’s nature-inspired world, we began asking what this archive might mean today.

The Victorian world of flower collecting, with books of floriography central to every home library, the custom of gifting flowers as a secret code of sorts, the history of botany as a backdoor to the study of science for women, and the poet’s rapt, deliberate attention to her flower “friends” has many branches out for us. Out of necessity, we began collaborating with two scientists, Dr. Kyra Krakos, professor of biology at Maryville University, and Peter Grima, forester and Dickinson herbarium scholar. Early in the project, Dr. Krakos enlisted her class of students to research plant stories of each of our 66 Dickinson Earthen Door species – and that was really the rabbit hole.

During a visit to the Missouri Botanic Garden, where Dr. Krakos sits on the board, we were granted access to their vast herbarium library, immense corridors of drawers and drawers of pressed plant specimens, including some that we were shown by Charles Darwin. We were also given a tour of the pre-Linnaeus book room with some rare plant books made as early as the 1400s, including Linnaeus’ original “Styema Naturae,” and many made with different printing/etching/painting techniques. We were able to leaf through ancient books on plants, sumptuous renderings in full color, or black & white, the fascinating history of plant archiving in one small room… Peter Grima has an acute understanding of both ecology, Dickinson’s herbarium and poetry, so we have leaned on him heavily throughout, especially for his nuanced knowledge on the science of the herbarium. Both scientists have been incredibly generous, and we would not be where we are without them. I think it’s been thrilling for us all to have a project that traverses art and science.

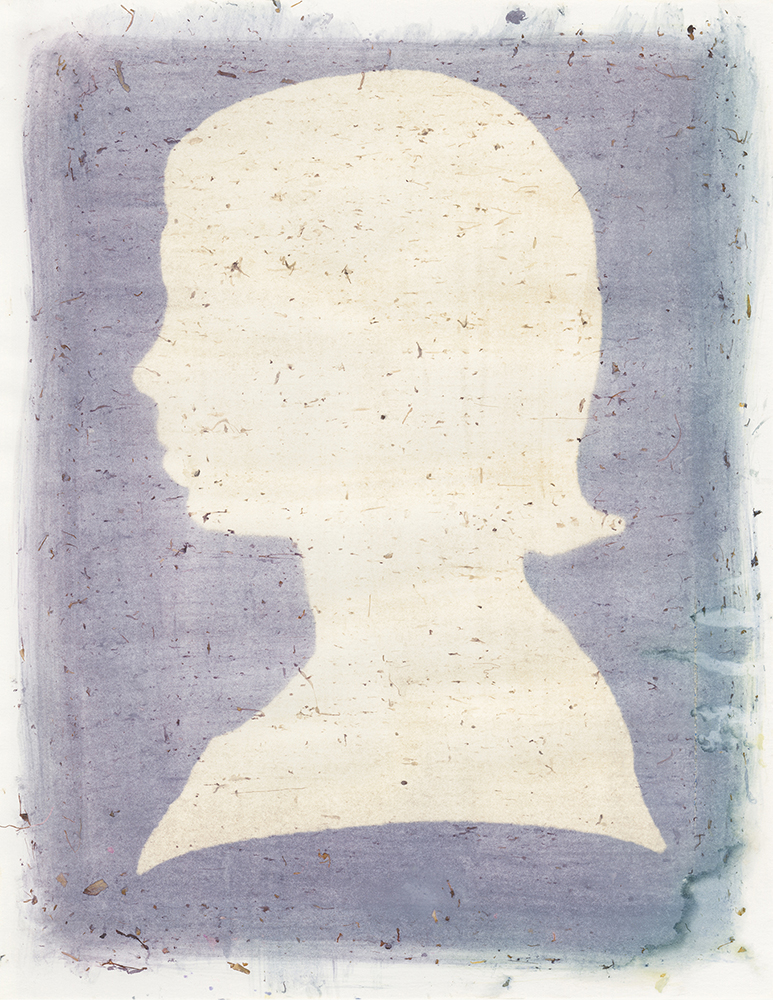

©Leah Sobsey and Amanda Marchand, Red Daylily, Emily at age 14 – negative, (from silhouette of Dickinson cut by Charles Temple, 1845)

Amanda: What is it like to collaborate long term as artists?

Leah: Collaborating long term requires nurturing. Much like the garden, for a collaboration to succeed in needs to be tended to—there needs to be sunlight and water—or wine! The beauty of collaborating with someone you’ve been friends with for over twenty years is the built-in trust that is necessary when collaborating. A deep respect and trust for each other’s opinion is key and something that Amanda and I have always had with each other. We started off in the pandemic on Zoom all the time. As we continue to work on new iterations of the project, we are constantly on calls, texting, shipping work back and forth by mail, at residencies together etc. We are both such work horses and that has been important since this project has been very full time. We keep each other motivated and talk through everything, which is invaluable in a collaboration. And most importantly a lot of laughter!

Leah: Tell us about your garden and its significance to you.

Amanda: Our gardens hold so much meaning for both Leah and I. Leah’s, especially, has been expanding since we started our project – we had to plant and grow so many species that were in Dickinson’s herbarium. We decided to use only plants in the herbarium and that she would have collected on walks and grown herself. Among our flowers, we included Dickinson’s favorites – Ghost Plant, the Violet, the Daylily, the Dandelion, Daisy. The single repeated species in our repertoire is the Rose because Dickinson grew so many types.

My garden is my mother’s garden, and already had a significant number of Dickinson species growing, though I did plant new ones, like Elderberry, Potato, Black and Red Currant. The garden is about an hour north of Montreal, in the Canadian Laurentians. It’s surrounded by woods and bordered by a lake – a family cottage. My mother was an avid gardener, a volunteer at the McGill Gardens, and when she was diagnosed with cancer a little over a decade ago, I photographed her garden at night for one summer in “Night Garden,” as a portrait of her, during what was to be her last summer. So, this garden is a place of communion for me, and a place of deep meaning. I remember her often in her nightgown, standing at dusk or dawn, talking to her flowers.

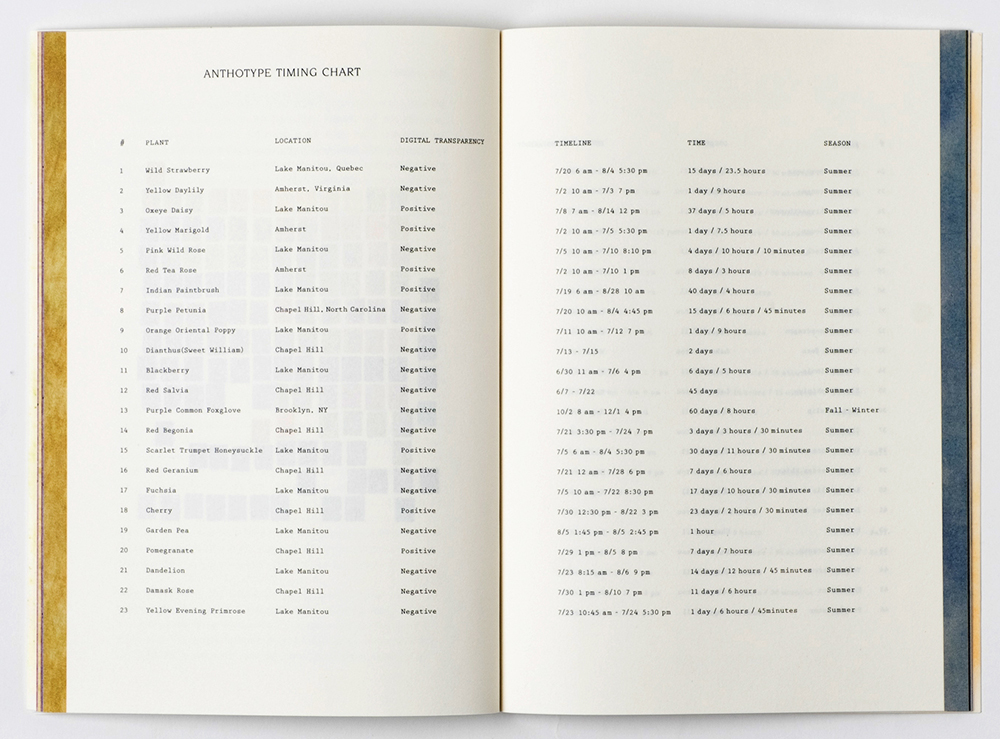

“If you take care of the small things, the big things take care of themselves,” Emily Dickinson once said. Working collectively with 66 of the poet’s plants from the 424 in the herbarium, has meant tending and care, and slowing down, and attention to the moment. Anthotypes are very slow to expose. We have a few that took more than 2 months, and many that took weeks and weeks. There is a language of attention and care embedded in the project. Leah and I are both mothers, and our families were involved, to varying degrees, as contact frames were carted in and out of the rain, or moved to sunnier ground over two years… We worked on this project during the pandemic, when we were at home and our children were at home, so these gardens and their tending extend into the language of nurturing, as artists and mothers. For both of us, these gardens are spaces of light and joy and family.

Amanda: How has your relationships to nature and plants shifted after making “This Earthen Door?”

Leah: It’s hard to express how much our relationship has changed to plants over these four years. We both have a deeper understanding of the role of plants in our lives, their importance, histories, their applications, and symbolic meanings. We both feel much more connected to nature and have loved the palpable, material, juiciness of life held in each plant and flower, the scent, their dryness/wetness, the many color surprises as you work with them as potions and on paper. The tenderness we both feel for the natural world has amplified through this work.

Leah: How is time a layer in the work?

Amanda: Anthotypes take time. Days, weeks, months… In terms of the process, we took note of exposure times for each plant, charting everything carefully – and we have listed these times along with their location and other relevant information in our book. As Leah and I were often in different locations—Leah in North Carolina and I, for the bulk of the project, in Quebec—the fates of our anthotype times differ. Leah’s exposures were often fast and furious in the middle of hot and humid southern summers; and mine were slow during the more wet and chilly summers in Quebec.

This project is a portal between past and present, 19th and 21st centuries. We are holding the hand of a ghost – so time is not only embedded in process but is truly at the heart of the work.

Amanda: Archives are an important component of your work and practice. Explain your interest in the archive and the importance of this archive.

Leah: My work has centered around archives and collections for over twenty years. I began photographing in museum collections after a Tufted Titmouse crashed into my kitchen window in 2006. As a photographer, my first impulse was to photograph it. Almost twenty years ago, that chance moment led me to the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, where I photographed some of the 10,000 bird skins in their collection. I felt powerfully drawn in, and while working with them, I understood why. A long-dormant childhood memory surfaced of a trip to The Field Museum in Chicago to visit my uncle, ornithologist John Fitzpatrick. I remembered watching him open the endless drawers where those beautiful tiny specimens lay lifeless and silent. Decades later, I imagined a photographic practice of bringing these birds to light from their dark, hidden places, reanimating them through photography. My work shifted about a decade ago, when I began partnering with scientists, leading to a cross-discipline dialog between art, science, and the humanities. Embedded in this work is an exploration of human-driven climate change and the ecocidal perils of the Anthropocene age.

After working intimately with Thoreau’s herbarium, which is also housed at Harvard, it seemed like a natural shift to work with Dickinson’s. My practice has always been experimental—a merging of past and present, materials and ideas, analog and digital, academia and process—and This Earthen Door drives— even dreams—that practice forward. I had been aware of Dickinson’s herbarium for some years, but a New York Times article “The Lost Gardens of Emily Dickinson” by Ferris Jabr (2016) reignited my interest in the poet’s mostly forgotten “flower” archive. The uncovering of the garden and the data that lays dormant in pressed plants continues to astonish and amaze me. The ability to bring dried pressed plants back to life, extract DNA and discover new scientific information is mind boggling. I love the idea that the archive becomes an archeology of flowers.

Leah: How has writing shaped your photographic practice and added to the project?

Amanda: My background is literature. My undergraduate degree was in literature. Most of my projects have a written element – this one included. When I graduated with my MFA in photography, I published a novel, “without cease the earth faintly trembles,” so writing and photography have always been a braid for me.

In my recent work, “Lumen Notebook,” I began working with books – exposing books on photographic paper outside, in nature, and making sun prints. The book titles, each on natural themes, were the engine for this work. I was interested in starting with language as a catalyst for an image, instead of making an image first then titling the work. So, text and image are a throughline in my work. Given my roots, I thought that working with a poet might bring things full circle.

This is a hybrid project, somewhere between literature, photography, and botany. Part II, our “research” section, includes 33 color compositions made with our plant pigments – color grids and circles etc. They are not anthotypes, but the pigment-coated papers before exposure – our photo papers. We took all of these papers and made compositions with them, using data from our research. They yield from numerous discussions with botanists and scholars, and each has an accompanying text. This section is called, The Chomotaxia. We borrowed the term from the 19th-century Italian botanist and mushroom hunter, Pier Andrea Saccardo, who created a color classification system he called “Chromotaxia.” In 1894, he composed a color chart standardizing the names of colors for fifty different plants.

These image/text pieces dive into botanical themes: endangered plant species, toxic plants, flowers used in the Dickinson kitchen, plant color alchemy, plants that symbolize love… We wondered: What would a 21st-century herbarium look like? We hope to publish the full work as a book, both Herbarium and Chromotaxia. The research and writing have been a huge undertaking, but I think the written portion will help reach a wider audience.

Amanda: This project is about the poet’s love of nature – and flowers, but what deeper themes does it touch on?

Leah: What can an archive and, specifically, this 200-year-old archive reveal? What might its excavation teach us about the world today – about invasive species, plant loss, natural habitats, about native American medicinal flowers, plant pigment color, plant toxicity etc. These are some of the questions we have been asking in this work.

This project touches so many different themes… On the significance of archives and collections for our collective memory, our current climate crisis, plant invisibility, botany, gardening, ecology, ethnobotany, eco-feminism, historical photographic process, time, love and death, poetry, and the importance of collaboration and shared knowledge. It is also part of an ethics of care and tending that is important in our lives, as educators, parents, and creatives.

Leah: How is an eco-feminist perspective embedded in the work?

Amanda: We know that plants underpin all life, with invaluable ecosystems, yet there are significantly more plant species left to chart than animal species in the world. This project addresses the phenomenon known as “plant invisibility,” in the hope that we might start to pay attention to the earthen world. Further, it is estimated that 3 of 4 of the planet’s undescribed plant species are threatened for extinction, including up to 45% of all flowering plants. Working with scientists brought to light the importance of investigating Dickinson’s herbarium also as a site of discovery – where ethnobotany, ecofeminism, and climate science could be central.

The definition of ecofeminism centers on the efforts of women working together to best galvanize and create, with a respect for organic, holistic processes. From the start, we really wanted to engage with non-toxic “darkroom” processes. The anthotype, as pure plant matter, can be composted and uses no toxic chemistry. Leah and I have both been lone artists on many projects – we have seen the rewards of collaboration in this work that hopscotches between our strengths and relies on scholars and scientists in an all-consuming project we could never have made alone. As we, globally, experience the real and existential effects of climate chaos, we hope this work will invite a diverse audience. Most importantly, in channeling this female, nature-revering poet, This Earthen Door points to where we must place our attention. Emily saw flowers as “friends,” and in community, we hope to shift our attention, even if only slightly, towards the vegetal matter that forms the basis for all human life.

Leah: What comes next for “This Earthen Door?”

Amanda: We are excited for Paris Photo 2025, where our publisher, Datz Press, will feature our work, and where we will have a book signing and give an artist talk. We are preparing for a large exhibition at the Brandywine Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, PA, to open May 2025. We are teaching an anthotype class together at Penland Center for Craft this coming spring, which will be fun, especially since we made such progress on the project there as residents. We will be having a solo show in 2025 with Rick Wester Fine Art, in Chelsea. And we will present our work next summer in Taipei, at the International Emily Dickinson Society conference, “Dickinson and Ecologies,” along with Peter Grima, partnering botanist, and Marta Werner, who wrote our bible, “Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life.”

Amanda: What has been the most joyful part of this work for you? What has been unexpected?

Leah: There are so many things that I’m thankful for in this project. For starters collaborating, especially in the early pandemic has been so meaningful. It can feel isolating as an artist, making work alone in a bubble and what so many people don’t realize is that being an artist requires a lot of business management. Sharing the load of not just the making of work but the management, strategizing, planning and ideating has been invaluable. Amanda and I work incredibly well together, sharing the load. We are amazing list makers! Accountability also plays a huge role in the making of work. It has forced me to work harder, try harder, push further because I know Amanda is counting on me. I don’t think Amanda and I expected that a flower project about Emily Dickinson would bring us around the world. What a delight to connect Dickinson’s flowers of the 1800’s to Korea’s flowers in 2024 (through our publisher Datz Press) and beyond.

©Leah Sobsey and Amanda Marchand, Artists Sobsey and Marchand in front of To Make a prairie installation (Self-compatible plants) at Photofairs, NYC

Amanda Marchand is a Canadian artist and educator living in New York. Her work focuses on the natural world with an experimental approach to photography. Recent honors include the 2024 Lensculture Awards winner; the 2024 London Photography Awards; the 2023 Julia Margaret Cameron Photography Awards; the 2022 Silver List (Silver Eye Center for Photography and Carnegie Mellon); Medium Photo Festival’s Second Sight Award Winner, 2021; Photo Lucida’s Critical Mass Top 50, 2021. She has held fellowships at the Hermitage Artist Retreat, MacDowell Colony, Mass MoCA, and Headlands Center for the Arts, among others.

Marchand’s work has been exhibited internationally in solo and group shows. “This Earthen Door” premiered at Photofairs NYC 2023, was exhibited at the Stephen and Peter Sachs Museum, and will be on view at the Brandywine Museum of Art, 2025. Marchand has published three monographs with Datz Press, “This Earthen Door: Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium,” (2024); Nothing Will Ever be the Same Again (2019); and Night Garden (2015). She has published several artist books including, The World is Astonishing with You in it: A 21st Century Field Guide to the Birds, Ferns and Wildflowers (2022). Her work is collected internationally in private and public collections such as, The Getty Research Institute, Stanford University Library, San Jose Museum of Art, the Center for Creative Photography, and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Her work has been reviewed in The Marginalian, Lenscratch, Lensculture, and ARTnews. “This Earthen Door” is represented by Rick Wester Fine Art. Marchand is represented by Traywick Contemporary, Koslov Larsen, Rick Wester Fine Art, and photo-eye Gallery’s Showcase.

Leah Sobsey is an artist, Associate Professor of Photography, Curator, and Director of the Gatewood Gallery at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro. Her multidisciplinary photographic practice reaches into the fields of nature and science, design, installation, and textile. Recent exhibitions include the Huntington Museum CA, Photofairs NYC 2023, The Stephen and Peter Sachs Museum, The Harvard Museum of Natural History, with forthcoming exhibition at the Brandywine Museum of Art, 2025, “In Search of Thoreau’s Flowers” at the Gregg Museum, and showcasing “This Earthen Door” at Paris Photo with Datz Press. Her books include “This Earthen Door: Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium,” Datz Press, 2024; “Collections: Birds Bones and Butterflies,” 2016, and “Bull City Summer,” 2013.

Sobsey has exhibited internationally, and her photographs and books are held in private and public collections across the US, including the Huntington Library, North Carolina Museum of Art, Credit Suisse, Cassilhaus Collection, Duke University Hospital, Fidelity Investments, Microsoft Collection. She has participated in numerous artist residencies,

including the Virginia Center for the Arts, Dumbarton Oaks, Penland, The National Park system, Hambidge, and Habla Mexico. Her work has been published in Artnews, New Yorker.com, the Paris Review Daily, Slate.com, Hyperallergic.com, The Telegraph, The Marginalian, and Audubon. “This Earthen Door” is represented by Rick Wester Fine Art, NYC.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026