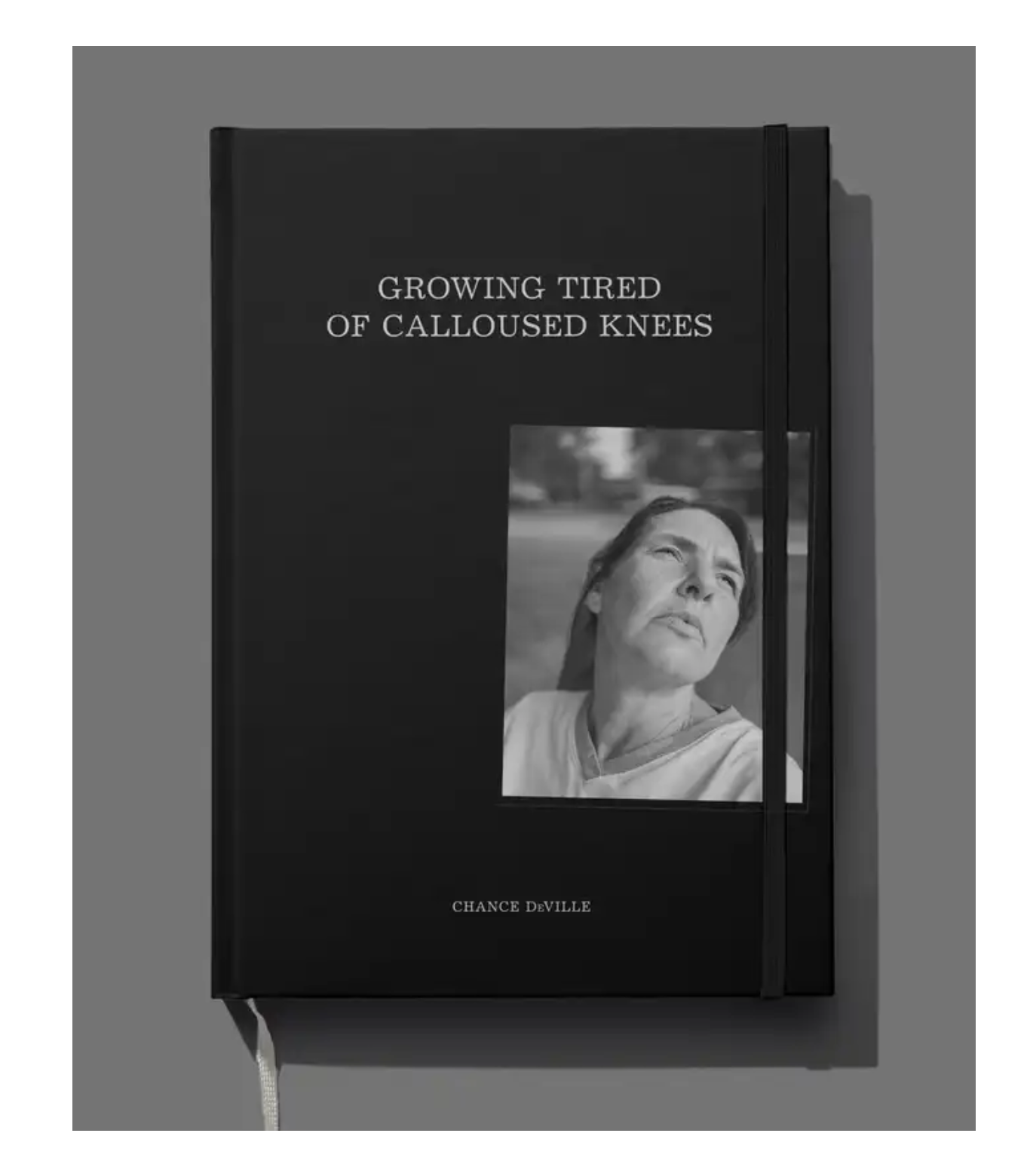

Chance DeVille: Growing Tired of Calloused Knees

I have followed the work of Chance DeVille for a number of years and I have always appreciated his bravery, talent, and honest telling of his growing up in a home fraught with domestic abuse and mental illness. After a decade of photographing his family, in particular, his mother’s struggles, he is releasing a monograph of the work titled Growing Tired of Calloused Knees. It will be published by Gnomic Book. DeVille is currently running a Kickstarter to raise funds for the publishing and I very much hope that you will consider supporting this amazing artist and the important work he is making.

An interview with the artist follows.

Growing Tired of Calloused Knees

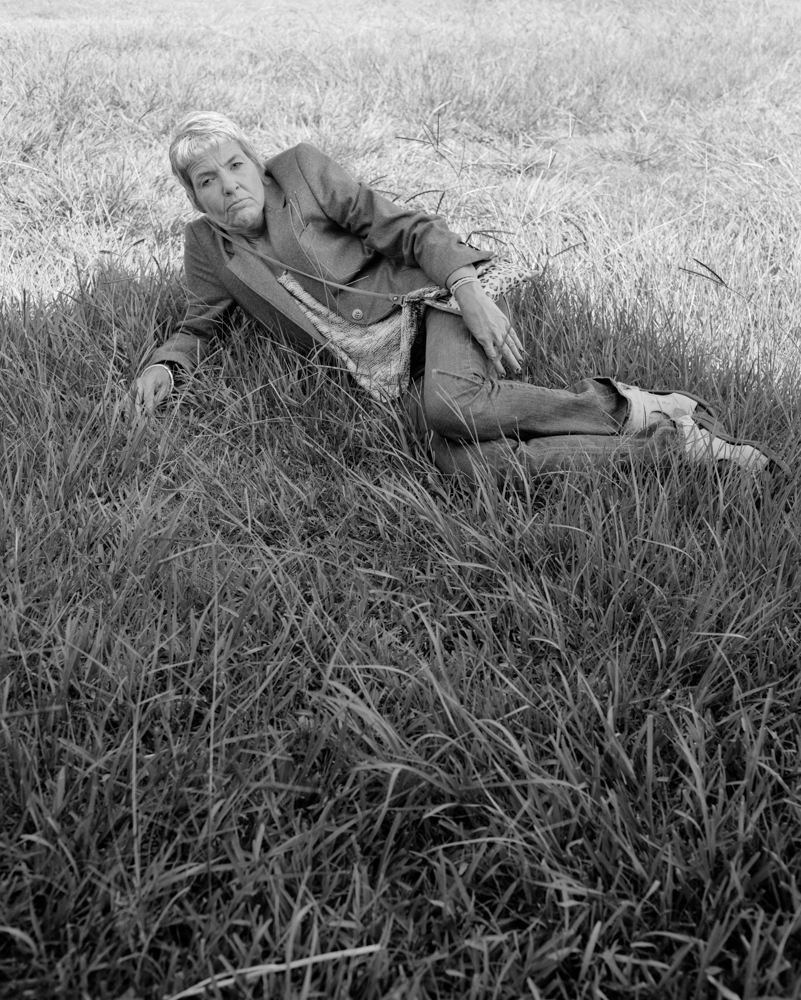

For the past decade, I have photographed my mother at our home in Louisiana. All of the images held here were taken within a 300 foot radius of the house, an act of stationary insanity.

“Growing Tired of Calloused Knees” attempts to carry the multitude of issues that stem from domestic abuse as the catalyst for the persistent cycle of mental illness, poverty, and substance abuse. I have photographed my mom as an attempt to understand this cycle on an intimate level. It’s a project that peels itself back, buckling from the pressure; a palatable view of troubled situations attempting resolve. The photographs and related material within desire to hold empathy, understanding, and care while showcasing the visual representations of these difficult topics. This work digs through to understand the overbearing weight of exhaustive circumstances that surround my family in particular, a space that holds grief and hope for both the living, dead, and worlds imagined.

Domestic violence, specifically against women by men for the case of this project, is a pandemic that is rarely addressed as such. In Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “The Longest War”, she writes about these alarming statistics, bringing to light just how often these instances occur. Solnit states, “A woman is beaten every nine seconds in this country. Just to be clear: not nine minutes, but nine seconds. It’s the number-one cause of injury to American women”. She continues by quoting Nicholas D. Kristof, an individual looking towards this violence regularly, “Women worldwide ages 15 through 44 are more likely to die or be maimed because of male violence than because of cancer, malaria, war and traffic incidents combined.” Providing statistics is necessary in understanding the breadth of the cycle that abuse starts of addiction and mental health disorders, but I am asking the viewer to look uncomfortably.

Due to my ex step-father, David, physically and mentally abusing my mother, Tammy, she was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and severe post-traumatic stress disorder. Neglecting psychiatric help, she turned to drugs and alcohol to suppress the disease. As a result of these changes in behavior and lifestyle, our relationship and power dynamic as mother and child changed drastically. This process is not only a photographic investigation of my mother, but a tool to build a new relationship with her through collaboration and documentation. These images show the tribulation of the permanent effects of abuse: poverty, disordered living, relationships left to be rendered. By showing multiple similar portraits where facial expression, weight, and coherency often change, the viewer is let in on the irreversible alterations that schizophrenia and addiction have attributed to my mother’s behavior. Photography as medium allows for an evidentiary result through a materialization of bodies and time that is not often felt due to trauma associated with David. These images are our reclamation — or perhaps, more bluntly, my attempt to resolve my endless grieving of my living mother. – Chance DeVille

©Chance DeVille, Mom in Grass Light, from Growing Tired of Calloused Knees, published by Gnomic Book

Chance DeVille (B.1994) is an acclaimed queer artist, educator, and writer born and raised in Southwest Louisiana. Their photographic and poetic practice addresses issues of cyclical violences of mental illness, addiction, and poverty. His images also tackle the American south, climate, queerness, landscape, and all of the nooks and crannies in between. They are currently based in Louisiana and New England.

Instagram: @chancedeville

Instagram: @gnomicbook

Congratulations on the book! Can you share what brought you to photography?

Thank you! I feel like I have one of those cliche answers to this question, which is to say that I have always been interested in photography since I was a child. I would obsess over any family photographic material that my Maw Maw had lying around and would constantly ask her to look at old photographs. My mom got me multiple cheap disposable cameras from the dollar store and eventually a little digital point and shoot that I would walk around and use whenever I was in my early teenage years. I came to the art world with absolutely no background in the field, just a cosmic attraction. I am a first generation college student, so my family didn’t have the background or knowledge around the language of visual arts, or quite frankly any interest in the bourgeois of it all.

My Maw Maw was a voracious reader, though. I memorized her library card number as a child and the house was filled with a constant rotation of the newest Nora Roberts and James Patterson novels. She always encouraged me to read and write, to find an obsession in different worlds and narrations, I’ve always carried that with me. Also, just to plug here the importance of public libraries and how much they changed my life as a little queer child in the south and to be so thankful for a family that encouraged that.

The first time I went to an art museum was when I was 19 years old, the museum of fine arts Houston, which was 2 and a half hours away from where I grew up. I’m not sure exactly what drew me to the medium at such an early age, but if I had to intellectualize it now I’d say it was my innate fascination and fear of death and the idea of immortality.

Your work is not only a powerful witness to domestic abuse and mental illness, but it’s a profound seeing of your mother’s journey. How has your project changed how you see her?

Doing this work over the past ten years has tested my limits of understanding and practicing empathy. I started out this project with a lot of anger and misunderstanding. Most of that anger has dissipated into a deep empathy of everyone involved in the cycle of abuse, even David. This work has made me understand the structures that are involved in placing people where they are placed, and how intergeneration trauma runs deep in people. Unfortunately, my mother got put in a place through manipulation where that violence was directed at her most destructively, and at my brother and I.

This abuse was life altering in every way possible. I lost the version of my mom that I knew growing up whenever we landed back in Lake Charles. What this project has changed the most is learning to let go of that version that I wanted to keep ahold of so badly and learn to meet her where she is, which is more important than any version that is “gone”. I need to love who is in front of me, every ache and mistake that’s led us to where we are. This is easier written than done, but I’ll let the photographs do that heartwork for me most of the time.

©Chance DeVille, Migrant Mother (Mom with Cicada), from Growing Tired of Calloused Knees, published by Gnomic Book

What has her reaction been to seeing her life in black and white?

Funnily enough she doesn’t ever ask to see the work. I’ve asked her myself multiple times over the years if she wants there to be some kind of approval process in place, but she says she trusts me enough not to, quote, “do anything she wouldn’t do”. So a lot of the editing of images is up to me.

There are a few favorite photographs that she does have, because she’s seen the final edit of the book. We have the same favorite photograph in the book, the piece titled, “Migrant Mother (Mom with Cicada)”, which was an image that was mostly her idea. It’s the last image in the book, a close up portrait of her with a cicada shell on her finger with her head tilted towards me under the massive oak tree in the front yard. We both love this photograph, a really tender moment shared hunting for cicada shells in the yard while we were bored.

It’s also heartwarming to know that this one of the last images I made of my mom, it resembles so closely the first image I ever made of her, in theory. The cycles in this book keep revealing themselves to me slowly, a gift from the work itself

How did the book come about?

After taking a few bookmaking courses in my undergraduate program, I always thought of this project ending up as a book. I’m a bit of a bibliophile, my mind just works in book form and I love that this work is going to have the opportunity to be on shelves for people to find. The book has already been pre-ordered by a few libraries, which is an absolute dream.

It came about by sending a few edits out to lots of friends and asking for advice on sequencing, heft, how the writing fits in and where, etc. I had sent Shane Rocheleau a few earlier edits of the book early on, and we ended up having a lot of studio talks about the sequencing of the book. I asked if he’d be interested to continuously work with me on the book, and he thankfully agreed. We worked on the edit for a couple of years before we started talking to Jason Koxvold at Gnomic Book. Having a continuous back and forth with someone I trust with the book has been so useful. I can’t urge artists enough to just send your work out to your peers and people you look up to. This community is much smaller than we think, and most people are just an email away. If your work is meant to connect, there’s nothing lost in putting yourself out there. You can’t start out further behind than you were, this book would’ve never been made if I hadn’t just randomly bothered Shane and I’m incredibly thankful for that.

I am curious how you deal with making a good photograph but also being sensitive of what/who you are sharing with the world.

I don’t think this is a skill I’ve exactly gotten a hold of. It’s a constant flux and flow. There are plenty of photographs in this series that will not see the light of day because I feel like they sit on the edge of being exploitative, and I’m very careful not to cross that line with this work. But it has been a struggle trying to figure out exactly where that line is. I will say, the biggest lesson with this work has just been to listen to my body and that nothing is permanent. Just because I try something with the work doesn’t mean it has to stick, and I’m allowed to draw my own boundaries when it comes to questions and what I’m willing to share with the art world. This has especially been true when it comes to how the series came to an “end”. There was a crushing feeling in my chest and in the bottom of my feet the last time I went home where I realized “this is it”. I knew that that was the last time I was going home specifically to photograph for this anymore.

Will you continue to photograph her or are you ready to move on to new work?

Throughout the years of making this work, I’ve continuously made other projects, but this work has always taken the most of my time and mind, so it will be really nice to feel like I have a “completed” version of this to share with the world so I can put more concentrated effort into other projects. I think this work will take on the likes of Baldwin Lee, Carla Williams, and Richard Billingham, where 30 years later the work will surface (again) with new work and work that was made 30 years ago since this is one of those projects that never truly stops. Hopefully my mother will live for a lot longer, as will I, and we can continue to make photographs freely without it bearing this heavy weight of projectness and sorting out all of the kinks. We’ve already worked through the hardest part of this, so I can’t wait for it to become a time capsule and see what we can unearth together.

As far as other work goes, I am currently working on a body of images titled, “Mass, Wake, Grave”. This trilogy is focusing on the fall of the patriarch of our family, my grandfather, and the chapters that came before, during, and after. It’s an image of my struggle with faith and visions after the death, the slogging through the destruction of our family home and dislocation after Hurricane Laura in 2020, and how identity gets tested in the throes of grief while surviving in Cancer Alley. I can’t help but be vulnerable in my work, it’s my only way I know how to share my work with the world. I hope it can be as well received as the work with my mom.

Thank you Chance, for sharing your story with us. I can’t wait to see the book! Readers, only 4 more days on the Kickstarter…please help him get to his goal!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026