Review Santa Fe: Duygu Aytaç: Ankara 1974

Today, we are continuing to look at the work of artists from the 2024 Review Santa Fe portfolio review event. Up next, we have Ankara 1974 by Duygu Aytaç.

Duygu Aytaç’s photography often explores themes of indoctrination, childhood memories and one’s place in a social group. Her work has been exhibited in Turkey and the United States since 2010. She immigrated to the United States in 2015.

Follow Duygu on Instagram: @duyguaytac_

Ankara 1974

In prison, my father met his childhood idol, an actor nicknamed the Ugly King. He befriended my dad, gave him cigarettes and asked him one day not to block his spikes during courtyard volleyball because it made him look bad in front of other inmates. The Ugly King was in jail that year because a man looked at him funny in a bar and he shot him dead. His first time in prison was for hiding a wanted revolutionary. Besides planning his escape every day, my father took to sharing his political views with the hashish addicts in the ward who in turn wanted to share their drugs with him. My father tried once and watched in terror as his right hand disappeared. To me it sounded like the only one who deserved to be in this emotionally degrading and physically disgusting place was the actor, but my father said no such thing.

Daniel George: This series deals with the history of your father’s experience as a political prisoner. What would you say was the catalyst for beginning to visualize this through your photographs?

Duygu Aytaç: The suffocating political atmosphere in Turkey right now is the main catalyst. The ongoing use of unlawful imprisonment as a political tool prompted me to think about my father’s own, relatively brief, prison experience in Ankara in the 70s as a 19 year old. Specifically the time he met his childhood idol, an actor nicknamed The Ugly King, while they were in the same prison ward. The timing of when I first sat down to write about it —early months of the pandemic— could have also played a role.

DG: I was very interested in the story you shared about visiting that museum and viewing the diorama on political oppression, which displayed conditions similar to your father’s imprisonment. Would you mind sharing that experience with our readers?

DA: The prison he was sent to is now a museum warning visitors about the dangers of political oppression. The hypocrisy is obvious even before walking in, as if political imprisonment in Turkey is a thing of the past. But after walking in, it was much more complicated. A stranger inside commented that my lips were quivering. In one ward, I heard a child ask his mother “they were jailed because they did bad things, right?” — which the tired mother left unanswered. Mannequins, a favorite of many small museums in Turkey, are often mocked on Turkish social media but here I thought they added to the hauntedness of the place.

In one hallway, I was thinking about one of the rare things my father shared with me about prison, a rule that all inmates had to chant “may the Allah-less communists be destroyed” before each meal, otherwise the young men on their mandatory military service would be ordered to beat the inmate up. Suddenly a young man approached me to ask if I could take his photograph. He said he came from Adana to do his mandatory military service in Ankara, and this was his day off so he thought he would go to a museum. As he was walking away, I realized I never asked him his name. I asked, he turned around, and told me my father’s first name.

DG: Since Santa Fe, I have been thinking about the effects of generational trauma, and how artistic practice can help process related emotions and feelings. Do you feel this work has opened anything up for you or your family? How so?

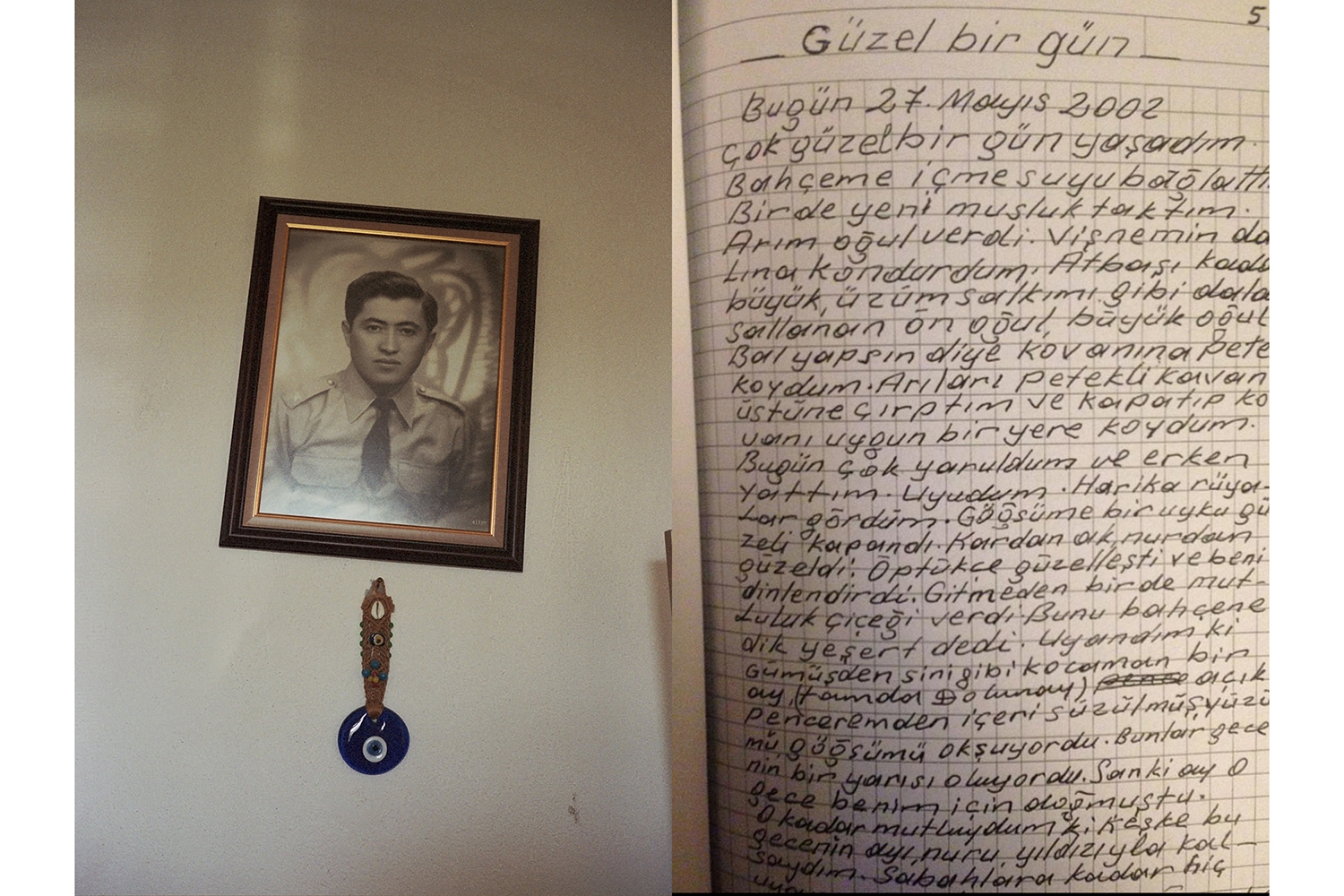

DA: It became quickly apparent that what I thought was a story about my deceased father was equally, if not more, about my living mother’s youth. When he died in 2011, my mother started writing about this period of their lives from the 70s but never finished it. She said she had to stop because her grief was too fresh. After I started the series, she went back to her draft so I could have more details for my project. “For the project” is now code for her exploring the layers that maybe got over-simplified or discarded along the way, especially relating to her own childhood and family dynamics, even if facing some of them is painful. Her going back to writing alone makes my endeavor worthwhile.

DG: Within the series, a lot of attention is given to younger people in Ankara. For me, this creates a thought-provoking dialogue between past and present narratives. Tell us more about your intentions here—and the individuals you choose to represent.

DA: When I first moved to the United States, I lived in Washington Heights. During that time I went on a road trip to the West Coast crossing through Iowa, Nebraska, Idaho and more. This dynamic of self-mythologizing cultural capital versus the neglected inland in Turkey was more clear to me after immigrating to America. Both of my parents grew up in rural central Anatolia, and they came from different Muslim denominations that typically do not mix in the countryside. So meeting in an urban, university setting in Ankara essentially allowed their story to unfold. Many revolutionaries of the time shared a similar background: young people from moneyless families in Anatolia, first in their family to go to university thanks to the free and secular education provided by the modern republic that replaced the Ottoman monarchy. But they were also posing questions that the nationalist or religious indoctrination they grew up with could not answer, so the ruling class at the time decimated them with the support of the US government. I do believe that almost every problem that plagues Turkey right now is rooted in that destruction.

My parents never romanticized this period of their lives, and when they rarely spoke of it, it was with an air of “we were children”. They emphasized naivete, but downplayed the bravery and self-sacrifice. I find this tension between childishness and courage very intriguing, and wonder how the age representation of ourselves shifts in our minds depending on the circumstances.

I am also interested in the emotionally charged symbolism of moving the capital from Istanbul to Ankara. Unlike Istanbul or Salonica, the city of Ankara had little significance for the Ottoman Empire so this under-photographed and non-touristic new Turkish capital in central Anatolia is essentially an invention of the modern Turkish republic. And therefore it carries all the hopes, accomplishments and disappointments associated with that young establishment.

DG: In our correspondence, you describe your motivations for not including your parents in this work, and to instead focus on the issues facing Turks that are rooted in the events that have affected your family. How do your photographs bring these matters to light?

DA: Despite the political oppression, Turkey is not a closed off country. It suffered its deadliest earthquake in early 2023 where tens of thousands people perished overnight, and by the end of the same year it was the fifth most visited country in the world based on number of tourists. Its people are currently suffering a terrible economic crisis while a catastrophic Istanbul earthquake looms in the future, but its pristine private hospitals are being raved about on the Internet. Since 2002 it’s been run by an Islamist government that largely relied on culture war polemics for its longevity, but the country’s crowning cultural achievement during that time has been the irreligious love stories it exports to the world as television series.

I understand that Turkey’s many contradictions and the adaptability required to navigate them are a big part of its allure. I also know that for those who actually live there, it is tiring. When I look at the people of my home country, I see exhaustion. But I also see a deep resolve for dignity and survival, a desire presented in different ways with varying outcomes of all Anatolian peoples past and present, despite all the indignities they have to brush aside and make light of daily. I don’t think this sentiment is untranslatable or Turkey-specific. My hope is to convey this emotional state, and also ponder on the possibility of genuine change by revisiting some of the more dusty lessons of the past.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026