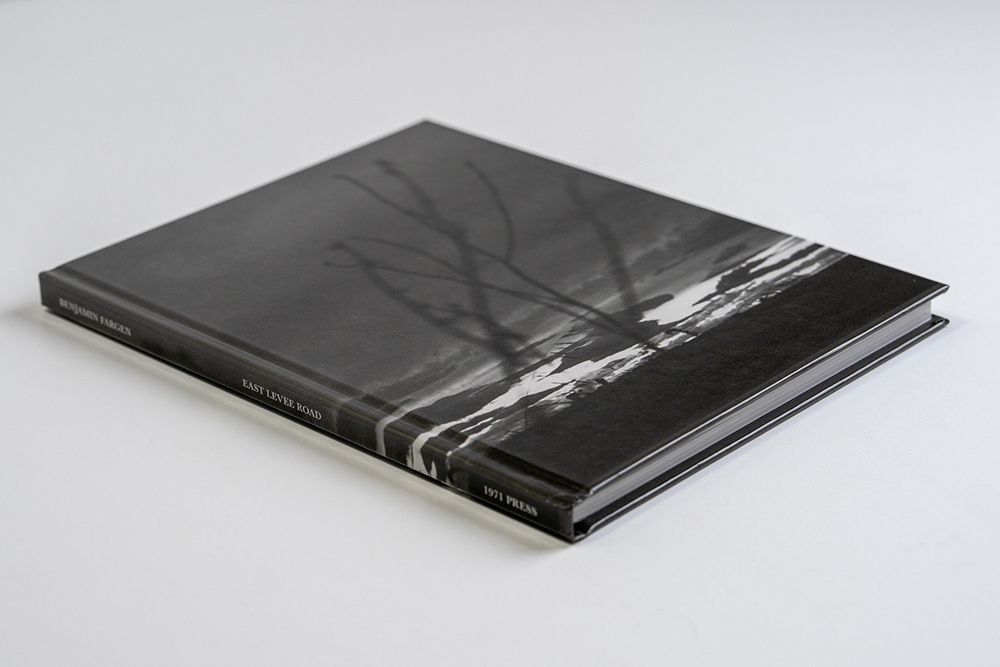

Benjamin Fargen: East Levee Road

Made during the COVID-19 pandemic, Benjamin Fargen’s East Levee Road encompasses isolation, while exploring humanity’s discards and witnessing the interminable force of the natural world. East Levee Road is seemingly in a state of decay, creating a serendipitous through line as the work was made in the pandemic era. While it seems like this may have been the right time for this work, East Levee Road did and continues to exist in this state outside of the pandemic. Knowing this informs the work at large and supports it with timelessness, giving the book context but not explaining everything.

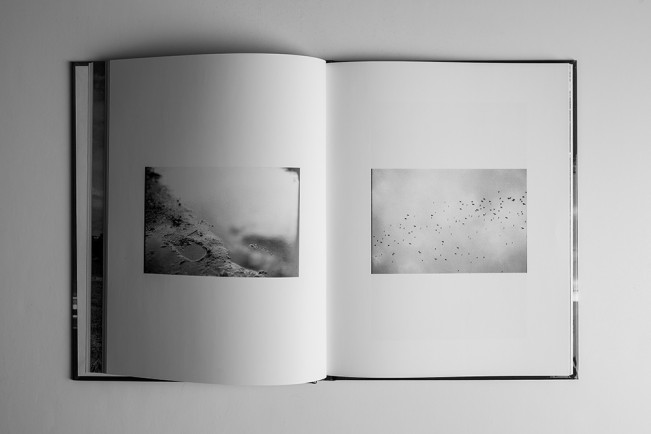

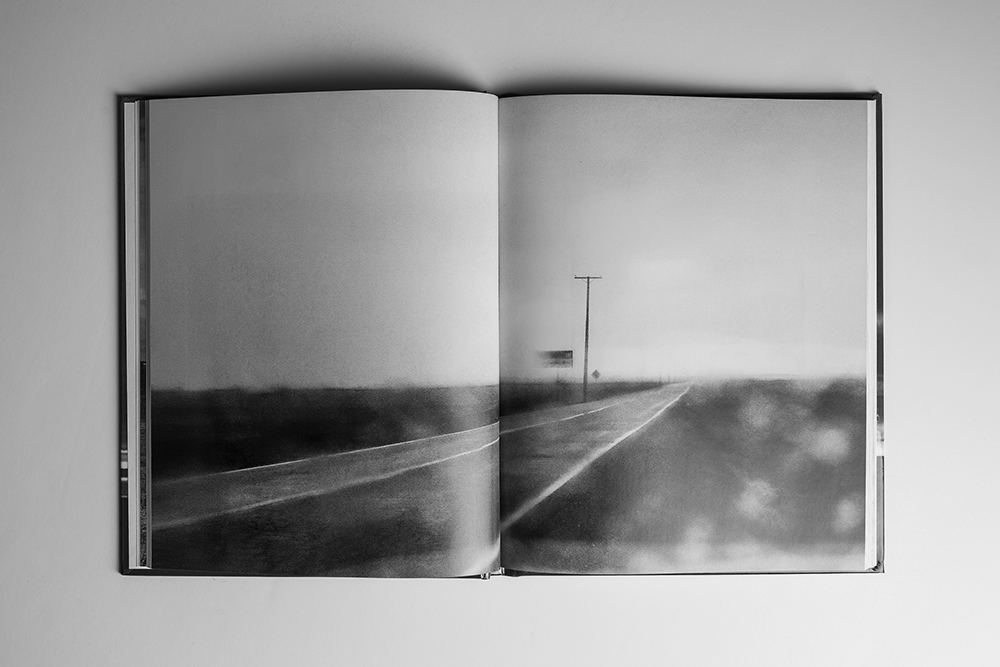

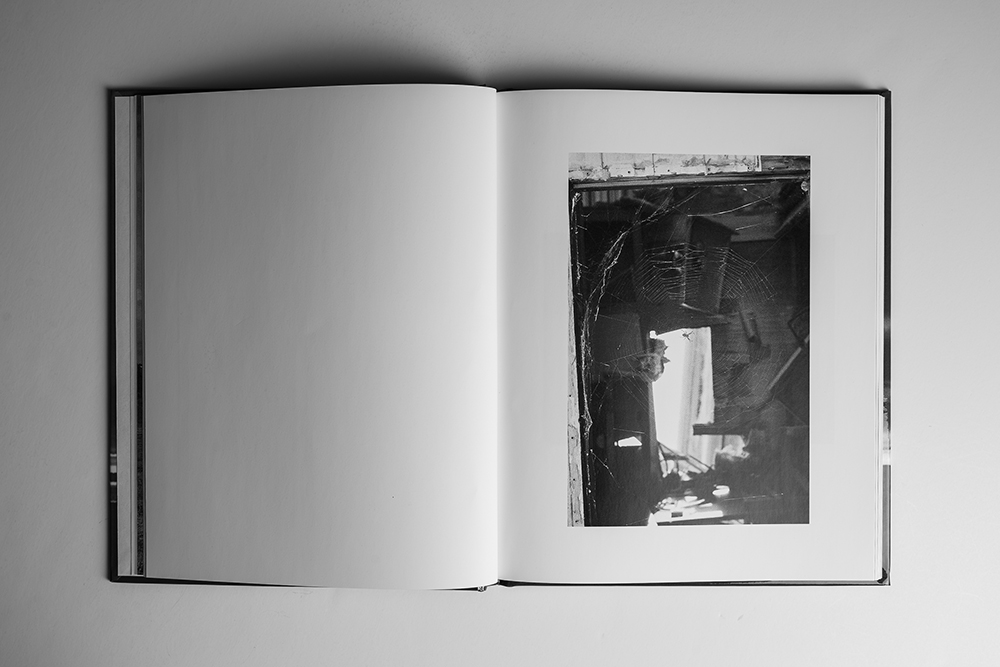

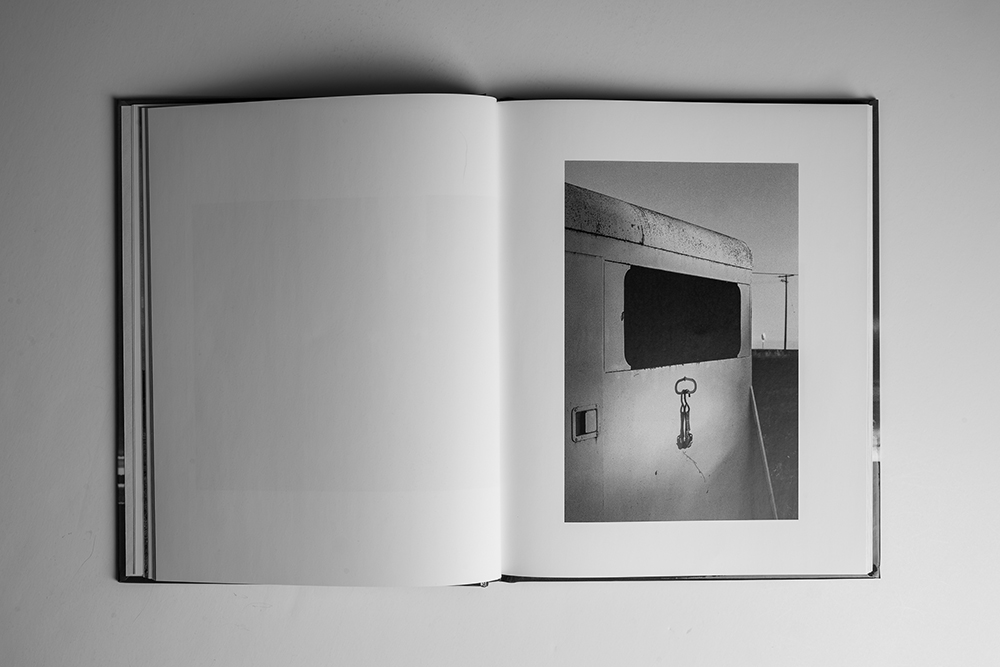

In pursuit of clear beauty, East Levee Road ultimately dives deeper to explore the consequences of humanity. Seeing the leftover bits of a civilization that doesn’t seem to exist anymore, the viewer is face to face with the impact of man-made structures and how that can outlast even the people who inhabit them. The viewer is left to wonder what gets left behind, how land is affected, and the resilience of nature. East Levee Road is riddled with plant life creeping back into empty spaces- trees growing through buildings, branches peaking through shopping carts, and grass claiming wire fences. There are no people featured in the book, suiting the emptiness of the land. Working through East Levee Road, the layered, sometimes unclear, beauty becomes increasingly explicit. The allure of this obsolete place is more and more sought after and the presence of debris is welcome, maybe even preferred.

Benjamin Fargen is a California-based photographer and documentary filmmaker whose work explores the interplay between nature, humanity, and the quiet spaces in between. With a background in visual storytelling, his eye gravitates toward the raw beauty of imperfection—faded roadside relics, the slow reclamation of man-made structures by the elements, and the solitude found in overlooked landscapes.

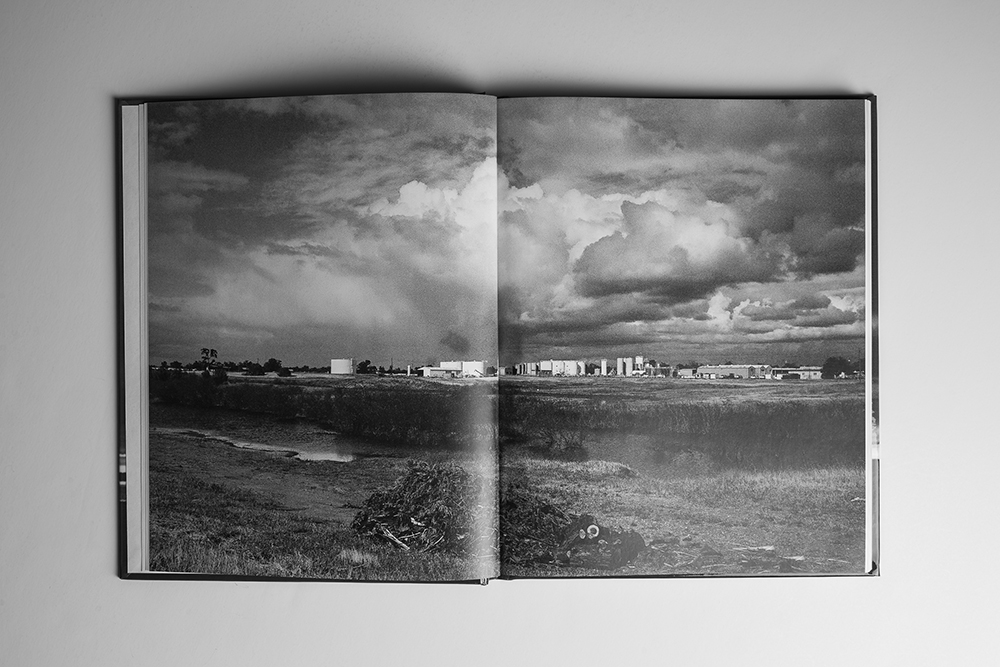

His recent project, East Levee Road, is a meditative study of a narrow stretch of land between Rio Linda, Highway 99, and the Sacramento River. Through atmospheric black-and-white and color images, Fargen captures a place in flux—where nature pushes back against development, and remnants of the past linger just beneath the surface.

Drawing inspiration from classic documentary photography and the moody aesthetics of film, Fargen’s work invites viewers to pause and find meaning in the quiet details of everyday life. His storytelling extends beyond still images into documentary filmmaking, where he crafts narratives that highlight the intersection of environment, memory, and human experience.

Instagram: @benjamin_fargen

East Levee Road

East Levee Road began as a personal escape during the stillness of the pandemic—a search for solitude in a forgotten strip of land between Rio Linda, Highway 99, and the Sacramento River. What I found was far from simple peace. It was a landscape where the natural and the man-made collided in equal measure, a place where beauty and chaos coexist in a delicate, complicated balance.

This project is an exploration of our relationship with the natural world and the traces we leave behind. It raises questions about the bonds we form with the land—why some connections feel unshakable and enduring while others seem fleeting or fractured. Through these images, I’ve sought to capture not just the visual contrasts of this unique environment but also the emotional duality it evokes: serenity and disruption, order and decay, hope and neglect.

At its core, East Levee Road is an invitation to pause, observe, and consider the ways in which we shape and are shaped by the spaces we inhabit. It’s a meditation on how beauty can persist in the face of chaos and how solitude can reveal truths we often overlook. -Benjamin Fargen

Jenna Banks: Can you tell us a little bit about your growing up and what brought you to photography?

Benjamin Fargen: I really didn’t start photography until quite late in life. My early pursuits were all music. I grew up playing guitar from the time I was about 12 and pursued music very passionately. When I became fascinated and kind of obsessed with photography was due to a documentary that I actually filmed on a friend of mine, Tony Natsoulas. Tony is this incredible ceramic artist, and during the filming of the documentary, we ran into a lot of situations where there wasn’t source photography available. We had to just do our best to capture some of these things. During that process, I was really enamored with still photography, even though I had a background in video and documentary work. I needed to explore it further, not only because I was loving it, but that it was going to end up making my video and documentary work that much better because of some of the slower pace aspects of photography.

So I didn’t really start fully digging into photography until 2014/2015, but I had an artistic eye in the sense that I was surrounded by, as a musician, other artists.

JB: I understand that kind of connection between the performance arts and visual arts. I have some of that that goes on in my family. My dad and my brother are both musicians, and I think that any creative mindset can lend way to other creative pursuits.

You’ve filmed and edited a documentary of the process of making this project. Now knowing that you started off in that video world ties that in even more. Was this something that you foresaw yourself doing to accompany East Levee Road to begin with?

BF: You know, I didn’t. As I got closer to the release of the book and it was coming together, I really thought I’d be doing a disservice to viewers if I didn’t use my expertise as a storyteller to further explain what these photos mean and where I was in my photographic journey at that time. I’d been working on it for three and a half years. It was about a month before the release date when I knew I had to do this documentary. I just didn’t think it would be as relatable and would mean as much to somebody who’s not a photographer or not into the style that East Levee Road was shot in. My hope was that people could connect a little bit more with it, understanding the whole point of man versus nature and the different ways that we all view nature from our families, politically, and regionally. If you grew up in the city and you didn’t have access to nature, why would you care about nature? An essay can only go so far as to explain what something is meant to be interpreted as, and that was really the big reason. Also, I always love a personal challenge. We had a few weekends to capture what I needed and edit this mini doc. It’s rough shot compared to what I would normally do, but I embraced that perfection was the enemy and we needed to get this story done. My son, who has very little background in videography, helped me, because I couldn’t film myself when I was narrating. So I had him behind the camera a few times and my wife as well. It was kind of a family effort and fun in its own right.

JB: It’s really lovely to know that was a family effort and you were able to do that together, especially when you think about the role that COVID played in your project. When I think of COVID, I think of lockdown and being at home. It’s so much family time. It almost makes sense that your family is so crucial in the process of the documentary.

BF: That’s a really great observation and one that I didn’t even think about, to be honest. Yeah, we were all here the whole time. Those experiences that were captured for the book were solitary. I would load up my gear and go out on my truck just to turn down roads I had never been down. My family wasn’t really part of a majority of that. So it is a neat closure there that they were involved in that filming.

JB: Can you share more about what made East Levee Road so compelling as a location? What about this place pushed you through the process of creating?

BF: For people that are not familiar with Sacramento, there was an Air Force base in between North Sacramento and then this region that the book was photographed in. It was people who were affiliated with the military or, after the war, settled down there. My wife’s mother and family actually grew up near that area, so it comes up a lot in conversation. I think that was the spark. I’d spent a little bit of time out there, but not a lot. Once I got out there and started to see the suburbs creeping into nature and the farms and ranches that probably were once really stunning, now kind of in disrepair, I think that was the initial intriguing part. My wife’s family comes from the Rio Linda area. Rio Linda borders up to East Levee Road, so that was the spark for sure.

JB: That family connection rings through again, wanting to learn more and connect. What were some of the constants you found yourself making images of throughout the project?

BF: Well, you know, early on, I was just capturing anything that I found interesting. The infrastructure is striking out there. You have this incredibly wide open, beautiful space, and then there is this electrical grid that runs straight down the levee. Shooting around that infrastructure is basically impossible. I wondered how I could encompass nature and this electrical grid. So it really started big. It was wide shots and getting the whole landscape. As the project continued, I started to hone in on more individual things.I don’t think it really would have been strong enough to be a project if I had stuck with just the wide landscapes because there’s some spectacular things to shoot, but there’s so much more beneath the surface that tells a story. So I’m thankful that I had that time to experiment and explore further because it kept taking me deeper down these microcosms of the bigger distraction of infrastructure and never being able to get away from that man-made element.

JB: I did notice this is your first monograph. Did you enjoy the process and can you speak to it a little bit further? What inspired you to turn this project into a book and was that something you always first saw for East Levee Road?

BF: I did not. In fact, when I started photographing there it was just for my own personal connection; to try to get to some open spaces to forget about COVID, to forget about the world, to experiment and learn, bring different cameras, try different films, and really have zero expectations. So I didn’t really ever think that it would be a book. But then as time moved on there were a few little magic moments along the way. One pivotal moment was the abandoned grain factory. I just happened to be at the right place at the right time, from a lighting standpoint. I had driven past this particular spot so many times and thought about stopping, but it was private property so I decided against it. Finally, I considered, you know what– this thing’s abandoned and I’m out here. After I got that developed film back, I had to get serious and even more intentional. It was time to fill in the blanks. At that point, it (a book) became a focus and a goal, as we all need, especially in art. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to make this a zine or an online PDF or something, I just knew it was going to be a project to complete, call it something by name and show it to the world. That was it.

I got to a point where I’d gone through a few attempts at sequencing and making some small prints and trying to lay them out, even doing a maquette. Around then, I got this email for a Trespasser Books workshop. It felt like time to let somebody else look at the maquette, get some other eyeballs on it, and get ready to take constructive criticism.

JB: That’s just such an important part of the process. You, at a certain point, can get so stir crazy looking at your own work, you have to show it to somebody else.

BF: Leaving the workshop, Bryan [Schutmaat] and Matt [Genitempo] said my job was to take the sequence, go back through every frame of the project, and fill in the blanks because I didn’t bring everything that I shot. We scheduled a check in on Zoom for a month later. I got to work and found so many of the images that were not brought to the workshop that were more powerful and had been put to the side because at that moment they didn’t work. A month later, when they viewed it, they mentioned this was incredible progress from where I was at the workshop. I went even deeper after that first month. I sent the PDF flipbook out to a bunch of other great photographers to get a little bit more whittling out. After that, the final PDF went back to Bryan and Matt and everybody at the workshop. I’m really pleased with the way it turned out because it accurately depicts the way I saw and how I felt about East Levee Road at the time. That to me is really the most important aspect of it, rather than any individual photo- just the feeling of it.

JB: Absolutely.

One of the most rewarding parts of the process is having the vision in your head or knowing the feeling you want to convey and being able to translate that and show it to other people. So I know that you finished your book not too long ago, but what do you find yourself creatively excited about or drawn too lately? What’s next for you?

BF: I have a couple different projects in the works. My wife and I take lots of long drives down in the San Joaquin Delta and it’s a really special place for us. Also, it’s kind of a political pivot point with the water that it provides for, not only agriculture here, but this project to put twin tunnels in that would pump more water down to the Los Angeles area. It’s been fought from day one and reduced from two tunnels to one and none of it’s been started. So the beauty of this incredibly important area has been something I’ve been capturing for the last few years as well. That could be a possible project where I do a series documentary that would be a companion to the book, which I think would be a really cool, exciting project.

Then continuing up north, we have this area, these buttes that are up between San Francisco and Tahoe. Chico Gridley has volcanic buttes and shelves that are really unique and I really haven’t seen anything like it anywhere else. There’s incredible farmland and ranches that surround these buttes, and I’ve started collecting a series of images from that as well. I definitely want to include some portraiture of some local people that live and work amongst that.

I have the skill set to do all the portraiture that I need, but during the pandemic, when we were disconnected from everybody, I really got out of the habit of making time and the connections to do that portraiture. So that’s a challenge to myself to bring human beings back into these projects and place them, rather than just have these empty spaces of just nature.

JB: I understand that. That’s something I struggle with in my own work as well, where I find myself uninterested in photographing people. I also can’t help but wonder if that’s a result of the pandemic.

BF: It’s entirely possible. I mean, if you’re photographing strangers, there’s an uncomfortableness that is always there at first and that’s something that when you’re not in regular practice, it makes it that much harder to not bring a human being into it. I can just go out here and be by myself and enjoy the solitude. I love that, it’s like everything to me, but at the same token, expanding on your work and progress as a photographer, those powerful portraits to mix with the nature is definitely a must for me moving forward. I still haven’t exactly figured out how I’m going to do that, but I’m working on it.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026