Skott Chandler: Near Misses

For the next few days, we are continuing to look at the work of artists who submitted projects to our most recent call-for-submission. Today, we have Near Misses by Skott Chandler.

Skott Chandler is a photographic artist, and Associate Professor at Black Hills State University in Spearfish, South Dakota. His work focuses on experimental film and digital processes inspired by the concept of truths and how a photograph can mislead and misrepresent because of the choices made by the creator. Skott’s imagemaking is about the perceptions of truth, the human relationships with time, spaces, fear, night, the unseen, and the unknown.

follow Skott on Instagram: @skottchandler

Near Misses

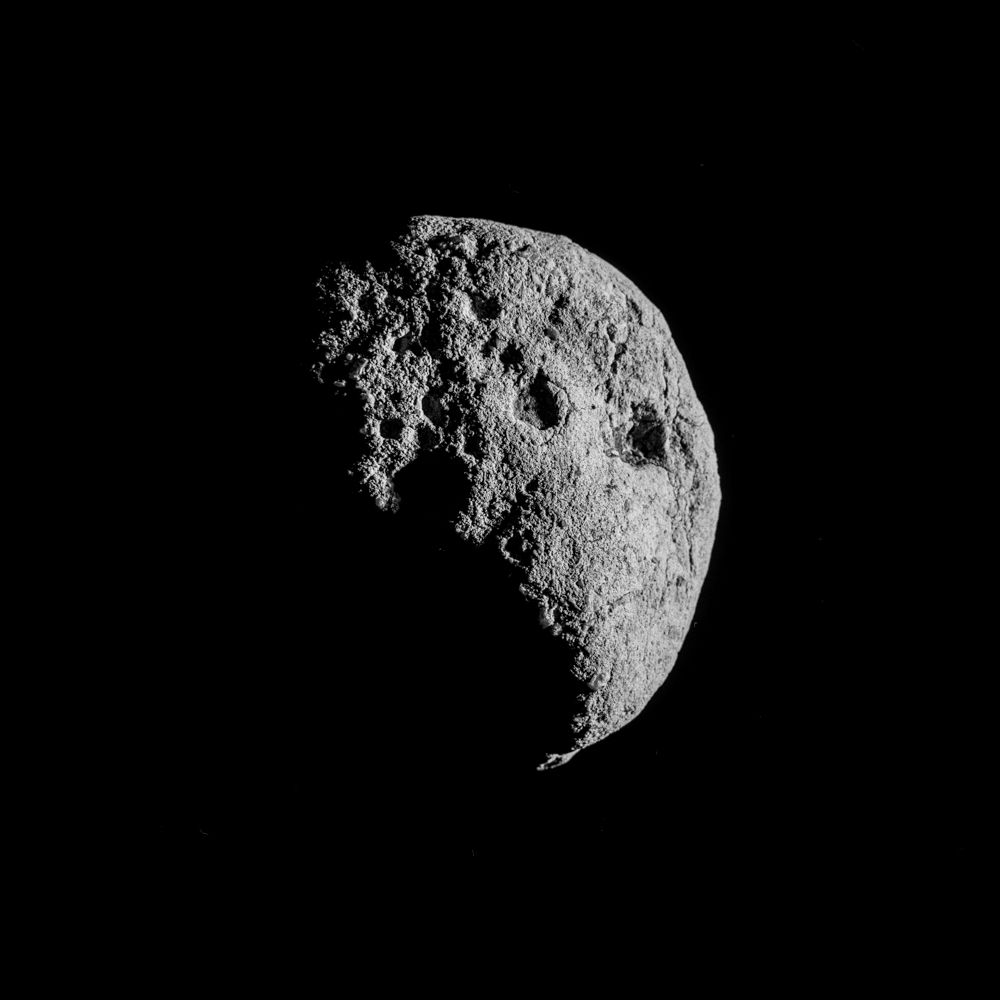

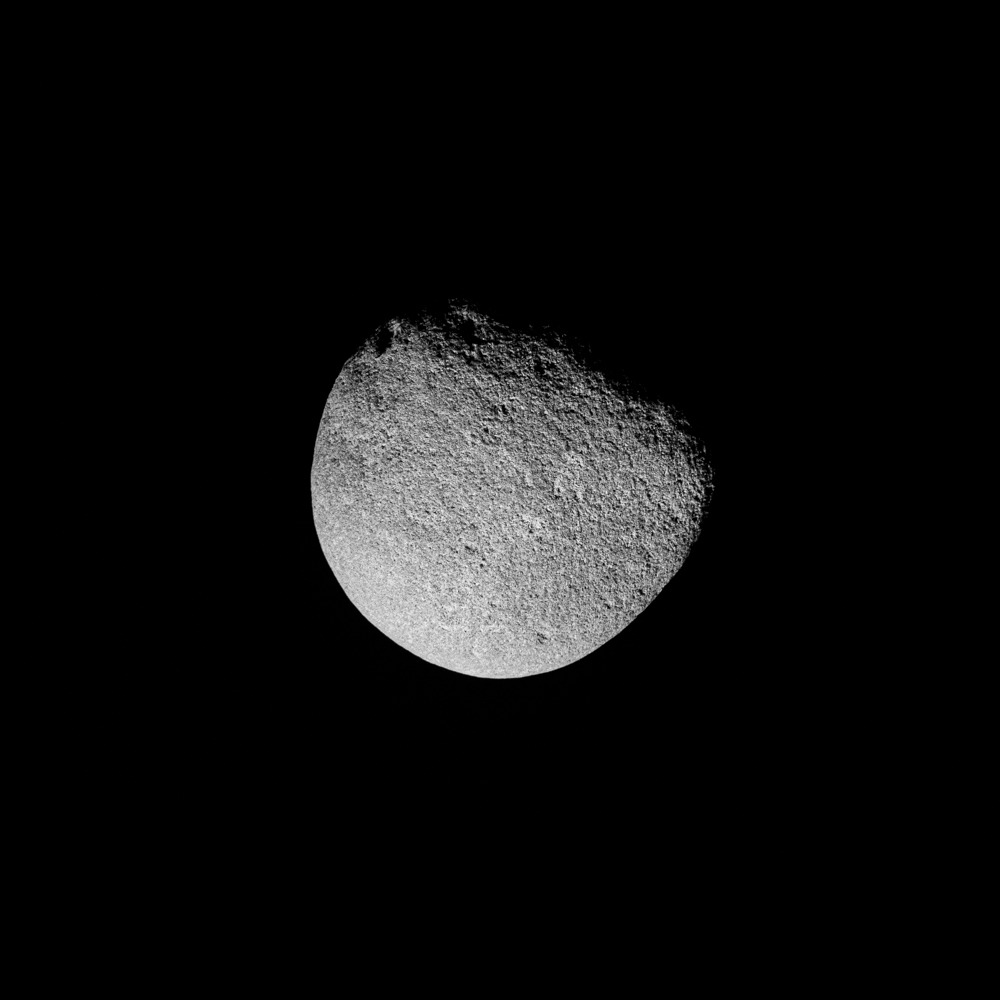

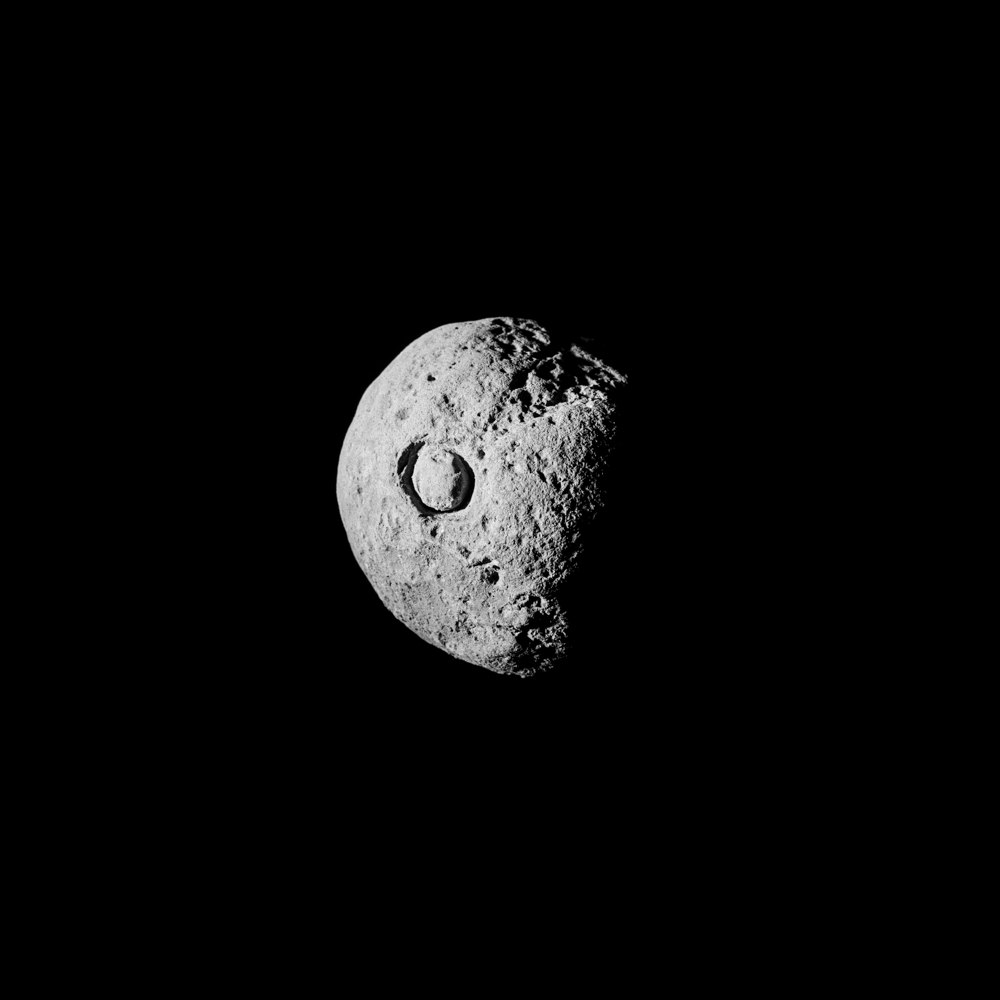

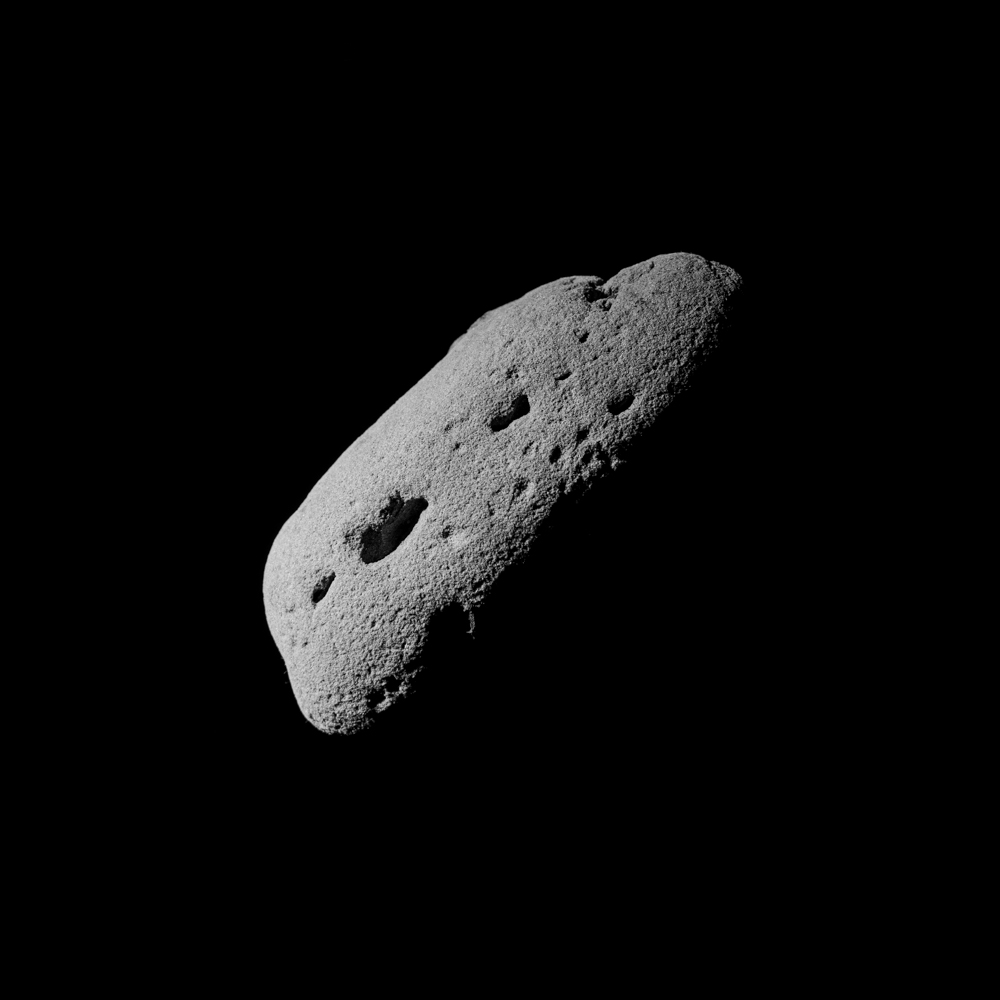

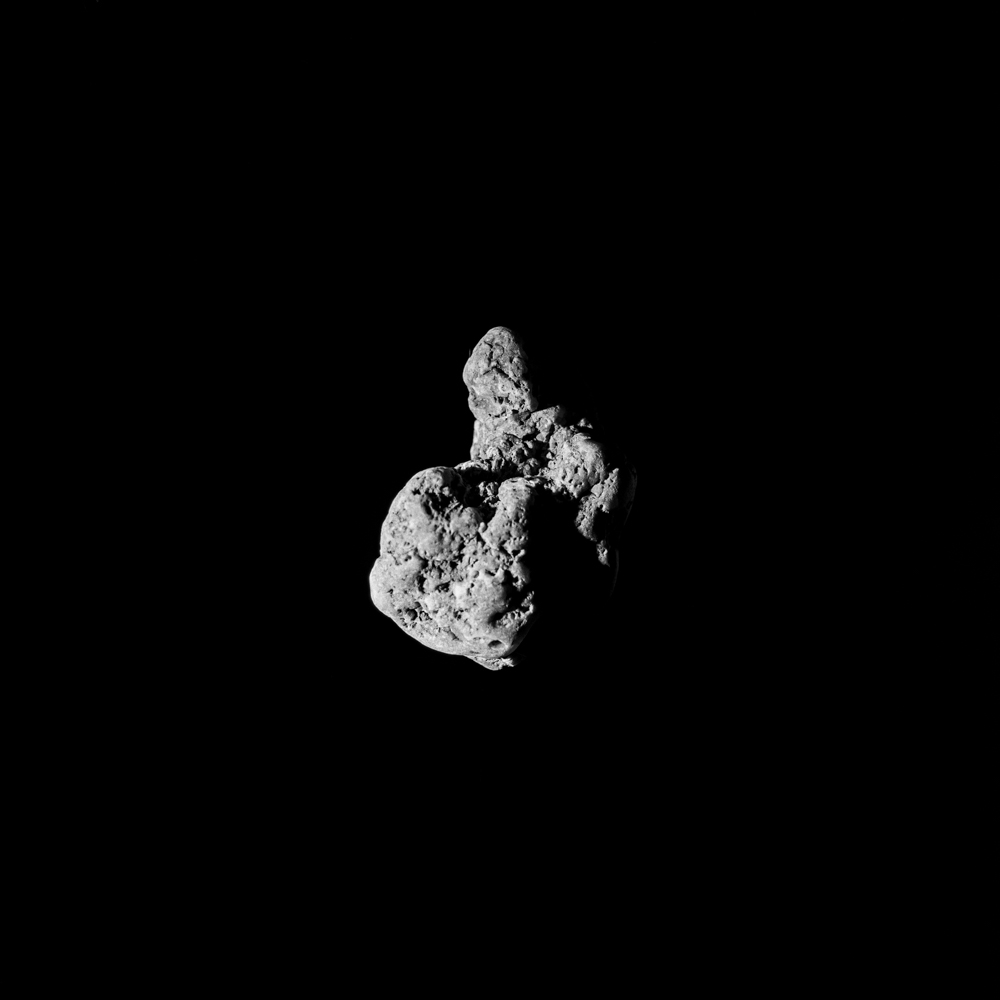

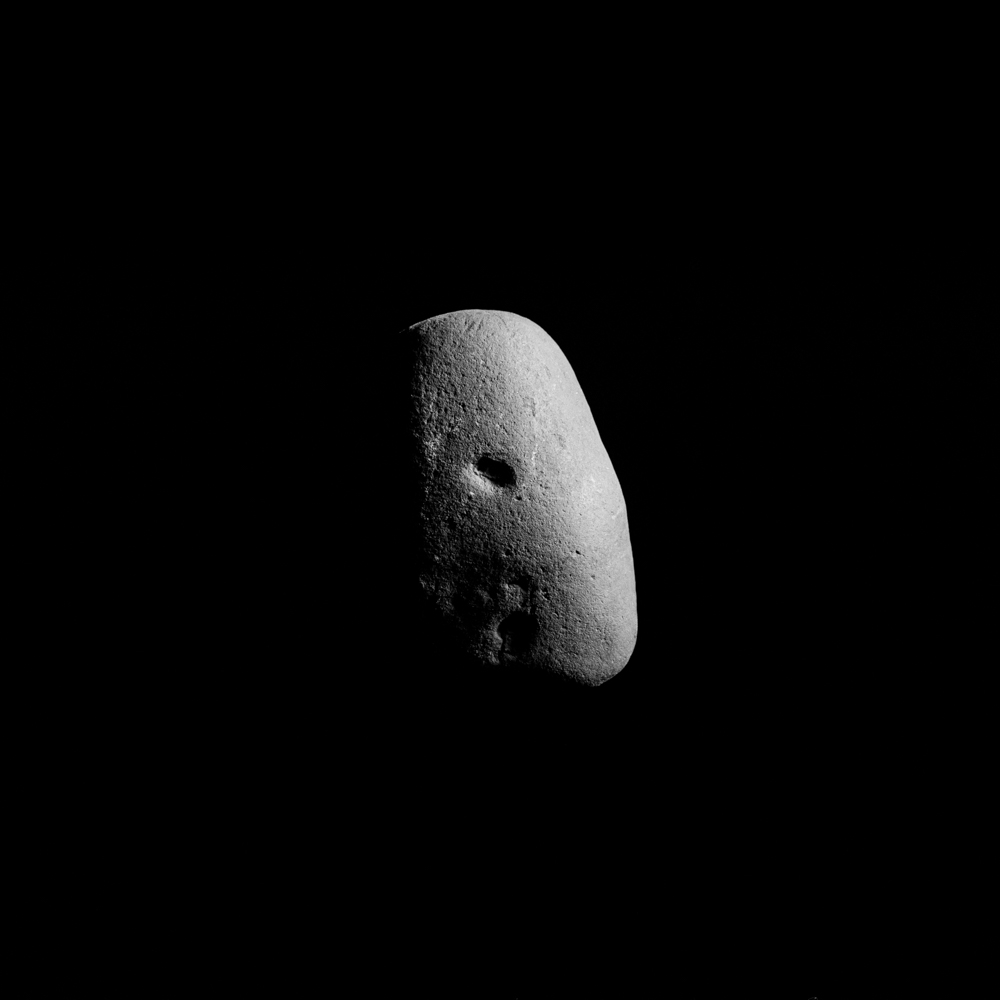

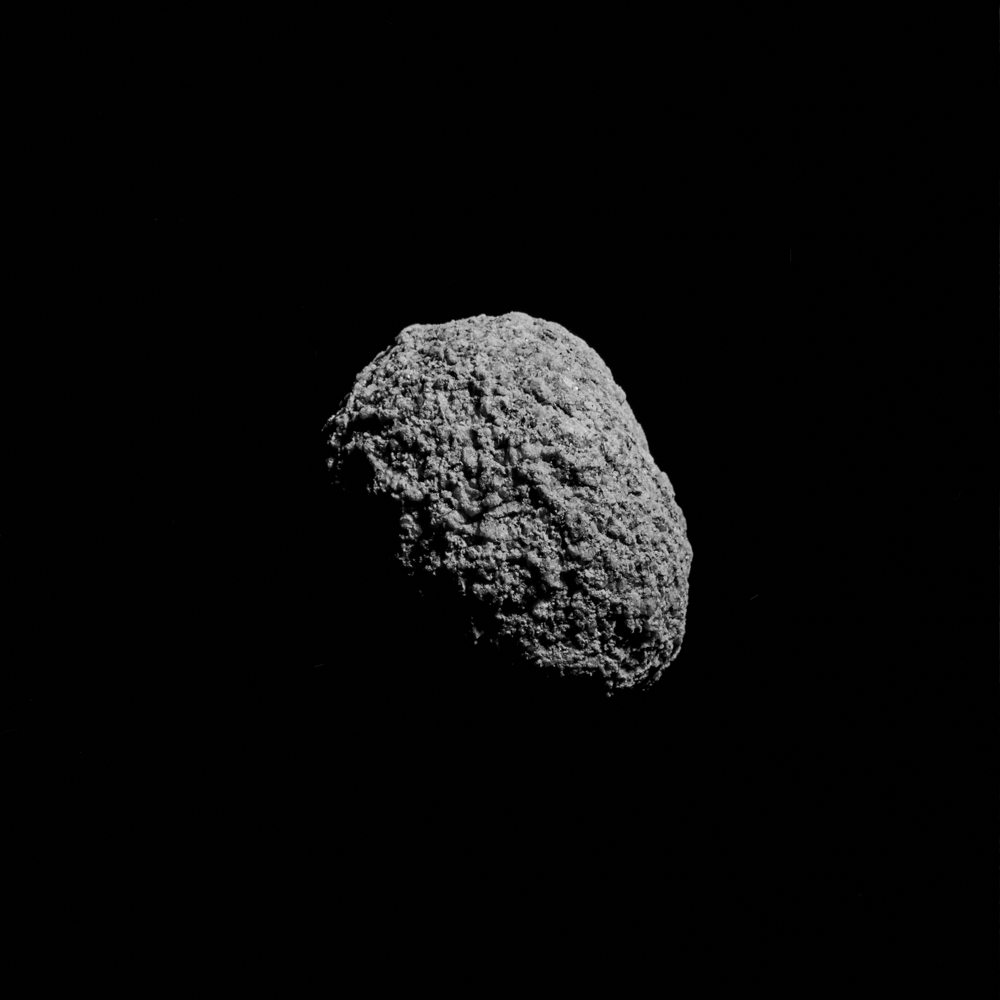

By mimicking the iconic NASA media of asteroids, “Near Misses” explores how humans interpret media and form opinions based on signifiers, and examines the delicate relationship between perception and reality.

This series represents the increasing ambiguity and complexity of our relationship with media and the need for critical thinking when interpreting the content we consume. By presenting terrestrial rocks that resemble asteroids and meteorites, I challenge viewers to question their assumptions and consider the limitations of perception. This process of reflection makes way for contemplation of how we consume and interpret information. Emphasizing that truth is not always as easily discernible as it may seem.

Daniel George: To begin, tell us what led you to start your Near Misses project.

Skott Chandler: I’ve always had an obsession with space and NASA. When I was a kid, my friend’s family had a flood in their basement. His Dad put a bunch of things out to dry, and one of them was a large NASA magazine on the Apollo missions and the moon landings. When I saw the wet magazine, I asked if I could look at it. I sat on their trampoline in the summer heat reading and examining the photos until it dried. Eventually, my friend’s Dad told me to keep it, and funny enough, it’s still on my bookshelf today.

Near Misses was specifically influenced by The DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) https://science.nasa.gov/mission/dart/. I couldn’t stop watching the video of the impact (https://dart.jhuapl.edu/Gallery/media/videos/dart_impact_replay.mp4). I kept thinking about how surreal it was that I was watching actual footage from space, but at the same time, how fake it felt.

Watching the impact was like watching a scene from Georges Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon. My train of thought led me to the long-standing myth of Stanley Kubrick faking the moon landing, and how to this day some people believe we have never been to the moon. Because of the faking accusations, people go to extreme lengths to prove the authenticity of the Apollo photographs. This made me think how a work of fiction (or allegory) can sometimes have the opposite effect, and make complex and existential truths more palpable, for example George Orwell’s Animal Farm.

A short time after the DART video, I was walking home from work thinking about the fake feel of the footage. There is a large strip of landscaping river rocks by the sidewalk. I picked up a rock, turned it around to observe the surface in the evening light and thought, “I bet I can make this look like the images of the DART asteroid.” So I brought it into the studio and started making photos of “asteroids.”

DG: In your work, you often lead the viewer to question their perception of what they’re seeing. I would describe this as a moment of immediate recognition (of subject matter) followed by a realization that the initial impression was mistaken. Along with Near Misses, your Bedscapes series does this as well. It’s playful, and I enjoy it. What would you say brought about this aspect of your creative practice?

SK: I think what brought me to this play with perception in my work is two things. First, my artistic life as a painter, where I loved the idea of Trompe-l’œil. My Bedscapes were a photographic Trompe-l’œil response to the contempt I felt for the prominence of generic landscape photography in Southern Utah, where I grew up. I wanted the viewer to perceive the images I created as beautiful, “classic” landscape photographs that were so beautiful that they encouraged a closer look. As they got closer to the image, the “landscape” would reveal itself as a simple bedsheet. Watching patrons in galleries grappling with their feelings as the image changed from a “real” landscape to a “fake” one was like a weird psychological experiment for me. I found that most people enjoyed the images more when the truth was revealed.

The second thing I think that leads me to play with perception is the old (pre Photoshop?) saying of “a photograph never lies.” I’ve always felt that saying comes from the photojournalistic, crime scene evidence area of photography. The concept never sat well with me, and still doesn’t. Probably because of my love for science fiction, and the worlds created by films and shows I obsessed over like The Twilight Zone, The X-Files, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Blade Runner. Even before my education in photography, I would argue that the only thing a photograph shows is that something was in front of a camera. Cameras lie because people lie. In a more academic semiotics context, I like to give people signifiers, knowing it will lead them to the wrong signs.

DG: In exhibition views of this work, we can see that these are displayed along with rock specimens, data charts, and video. Could you talk about your intentions of creating an almost science-museum like experience with all this?

SK: It was the intention to make the gallery feel like a science exhibit. That choice again goes back to creating a false narrative to alter the viewer’s perception with how they will interact with the media in the gallery. For that exhibition, I put actual scientific information on NEOs (Near-Earth Objects), and graphs early in the show. A bit of fiction with a drop of truth to sell the illusion.

The project statement was placed at the end for the exhibit, where the gallery looped back to the start of the images by the main door. I hoped one of two things would happen. That people would completely ignore the statement and leave thinking I had NASA quality image making capabilities, and instill a sense of dread of a cosmic threat to humanity. If they did interact with the statement, I wanted them to re-engage with the work from the beginning, with new information to see if they can identify places in the work where my lies are exposed. Regardless, my goal was to make the viewer acknowledge our place in the cosmos and how small and delicate our existence is – or as Carl Sagan said in the Pale Blue Dot, “The earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena.”

DG: As you were making this project, did you gain any new insights into your relationship to media, perhaps regarding your own assumptions and/or limitations of perception? What would you like the viewer to make of all this for themselves?

SK: I did gain new insight. Ironically, the DART impact video was from September 2022, and I started making my images around November 2022, when ChatGPT and Dall-e were creating a lot of controversy and discussion about how no one will be able to trust what they see online because it can all now be faked with AI. I thought about how images have always been able to be faked, be it constructed scenes or Photoshop. I decided to lean into the idea of “real” images, and add a little depth to my project by making the photographs on film. The final photographs in the series are almost exactly the same as the image from the negative on the contact sheet (https://photos.app.goo.gl/Zs6iJ416HtudeMw3A).

Working on the images made me think of how easily images are misidentified, represented, and labeled incorrectly online, even before the flood of AI-generated content. Some of the misinformation could be innocent or intentional. It makes me think back to an article in 2014 titled, “Dutch Girl Fakes a 5-Week Vacation to South East Asia by Posting Phoney Photos to Facebook.” I read the article and thought how scary it is that we as a culture have become so trusting of the media we interact with online. How many times has a young photo student searched for an Ansel Adams photograph and ended up putting a mislabeled Edward Weston photograph in their presentation? We live in an image-saturated culture, consuming media without much thought. There are also downstream effects when incorrectly labelled media continue to circulate amongst vetted and authenticated imagery. Creating this project encouraged me to pay attention and verify my assumptions with the media I interact with. I hope this project will encourage others to do the same with media they encounter, be it traditional film photos, digital photos, or AI-generated imagery.

DG: You write that this series highlights the importance of “critical thinking when interpreting the content we consume.” How do you feel these images help accomplish this?

SK: By misleading you. One of my favorite artistic choices is the beginning of the Cohen Brothers film Fargo. For those who haven’t watched it, before the film starts the audience is presented a black screen with white text reading:

THIS IS A TRUE STORY.

The events depicted in this film

took place in Minnesota in 1987.

At the request of the survivors,

the names have been changed.

Out of respect for the dead,

the rest has been told exactly

as it occurred.

This simple text is an intentional deception by the Cohen Brothers, as the movie is entirely fiction. But that text switches something in our brain as the viewer, and makes us engage with the film in a more literal way. To me, it makes the audience grapple with the reality of the horrors humans are capable of.

With Near Misses, I reference images in the public consciousness surrounding space exploration, but the images are created using terrestrial rocks picked up by the sidewalk and photographing them to feel “correct.” With my blatant deception, I want viewers to think about our place in the universe, to question their assumptions and consider the limitations of perception. Has information been included or omitted with the intention of leading you to a specific conclusion? This is the thought experiment that I try to use when I watch the news, read an article, or look at pictures.

I think everyone should question how they consume and interpret information. I want the media within Near Misses to remind us that truth is not always as easily discernible as it may seem, and know that even a work of fiction can speak to larger truths.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Gadisse Lee: Self-PortraitsDecember 16th, 2025

-

Scott Offen: GraceDecember 12th, 2025

-

Izabella Demavlys: Without A Face | Richards Family PrizeDecember 11th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 2November 27th, 2025