Photography Educator: Meghan Kirkwood

Photography Educator is a monthly series on Lenscratch. Once a month, we celebrate a dedicated photography teacher by sharing their insights, strategies and excellence in inspiring students of all ages. These educators play a transformative role in student development, acting as mentors and guides who create environments where students feel valued and supported, fostering confidence and resilience.

For the month of April, I am delighted to feature the words and work of Meghan Kirkwood. Meghan is the Associate Professor and chair of undergraduate Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. Though I haven’t had the opportunity to meet Meghan in person, her photographs, her students’ work showcased below, and her thoughtful responses to my questions clearly demonstrate her deep commitment to inspiring and motivating her students to cultivate their own unique perspectives through photography.

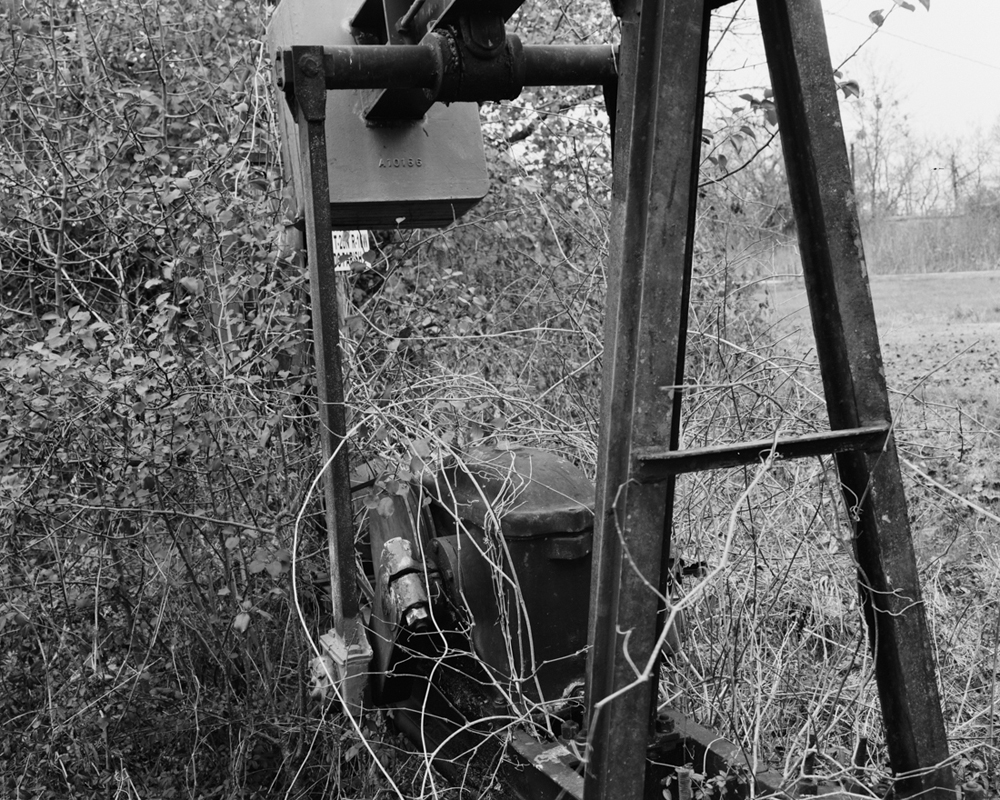

This article starts with works from Meghan’s project, Orphan Wells, Caddo Parish.

Vast regions of the United States have been transformed by the insertion of massive pipelines, construction of refineries, and displacement of communities due to air and groundwater contamination. Yet, despite the scale of these impacts few have knowledge of contemporary oil landscapes or the people who live there.

My images respond to this lack, and reveal the aftermath of oil extraction activities on land and livelihoods, display the interface between industrial and residential spaces, and the arc of boom economies to their eventual decline. Through my work in northwestern Louisiana, I use large-format photography to consider the invisibility and hypervisibility of oil and gas development and the environments it reshapes.

And while I engage with environmental and social issues of concern, my work does not present a clear editorial set of narratives. Rather, I seek to work within what Paul Graham describes as a “lyrical documentary practice,” a way of photographing that extends from artists such as Robert Frank; that “resists both narrative arcs and the drama of photojournalism or staged photography, grappling instead with the world as it is, in all its tangle and wonder.” My approach is further influenced by photographers such as Robert Adams and John Gossage, who model ways of studying landscapes that present man made interventions with understanding and calm analysis in place of pity and fear.

I was eager to learn how Meghan balances her family life, her career as an educator, and her work as a contemporary artist. Below, you can read her insightful answers to my questions.

ES: How and why did you get into teaching?

MK: I got into teaching because I loved being in school and surrounding myself with people who were smarter than me. I also loved the ways a school setting put me into contact with people who were really different from me—either the work they did, the subjects they studied, or their own identities. I felt like teaching would give me a way to keep growing as a person (and as an artist) in a meaningful way through the different ways it put me into contact with others. And once I actually started teaching in grad school, I found that part of the job was just as much fun as I thought it would be.

ES: Did you have an influential photography mentor or teacher? What was their biggest impact on you?

MK: I have been fortunate to study with some truly phenomenal photography teachers. My professors at RISD, Deborah Bright and Steve Smith, both had a big impact on me and the work that I make. Through her career Deborah Bright modeled a way to be an artist and a writer that made me think I could find a place for both in my own career without having to jump camps, so to speak. Steve Smith is an incredible imagemaker and thinker about photography and I regret that I wasn’t smarter and better able to learn from him when we worked together.

As instructors both Deborah and Steve were incredibly generous with their time and feedback and modeled a kind of honest, direct-yet-not acerbic critique that challenged me to be a better, more responsible photographer. Both of them taught in a way that showed you what was possible—technically and conceptually—for your work and left the door open for you to walk through it. In different ways I learned from both of them, the importance of committing to the work and developing your own questions.

ES: What is the most meaningful part of your job?

MK: The most meaningful part of my job is helping students make work about something they care about and then care about their work. In my current and previous positions, I get to work with a lot of students who are not art majors and who just love or know they have an interest in photography. Being able to help introduce these students to a bigger world of image making never stops being exciting. And, working closely with photography students over many classes to hone and grow their practice also feels like a privilege.

I would also say—for those that might need to hear it—that the admin side of my job can feel meaningful too. On the other side of all the meetings and emails, there are chances to make facilities, programs, and student experiences better. It gets a bad reputation, but I’m finding the admin work can present a whole new set of ways to work meaningfully on behalf of students.

ES: What has been your biggest sacrifice?

MK: I think my biggest sacrifice—if I mean sacrifice as the giving up of time and resources—has been having children. Having kids has been the greatest joy and privilege of my life and I’m thankful every day that I get to be someone’s parent. And, I also recognize that for most of my career as a photographer, I did not have kids and could commit to projects and professional opportunities (involving travel and money) that I just can’t anymore because I’m a parent to two kids (Rowan, 4, and Seamus, 2—very cute and very loud little people). And the professional limitations of that reality are, well, real for photographers.

I think a lot about how this part of being a person with a career in photography and teaching was invisible to me for so long. And now I look at a lot of photographers I admire and whether or not they have children, and if they do, how do they manage to make it work. Can you be a successful image maker who shows and publishes and makes compelling work and be a present parent at the same time? Can you do it without having the support of extended family? Extensive financial resources? I think the answer is yes, but I wish there was more of a conversation both about how people make it work and what being a parent has done to expand the way they see and work. There are so many great things that being a parent has had for me and my own work and I wonder how other artists identify these impacts in their own practices and lives.

ES: What do you fear the most?

MK: I have a fear of elevators, airplane depressurization, and those dreams where you lose your teeth that are genuine and probably suggest that I need some kind of professional help. But, apart from that and the general parent fear of not being able to support kids financially and the various ways they might choke on things, my fears are pretty school-oriented. I worry about the challenges art students face to afford college, the pressures universities are under to professionalize curriculum at all levels, and how much harder it is for professors to focus their attention on teaching (with increasing expectations for service, impacts of budget cuts, challenges of a changing economy, etc).

I also fear that phones are impacting studio culture in a way that we’re not really talking or doing anything about. I think a lot about how the critique space feels a lot more fragile than it did a decade ago and how much of that may be due to fewer ways that we build trust in the classroom. If you jump on your phone each time there’s a break or to avoid potential awkwardness talking to your neighbor, how can you get to know the people you’re studying or working with? How can you build trust with your peers before you have to be vulnerable, either through the sharing of your work or by offering anything less than praise for someone else’s work? I think that the network of peers you make in art classes is one of the best things you can get from school and I fear that we’re not doing enough to help students develop these connections (by talking honestly with them about the phones).

ES: What keeps you engaged as an educator?

MK: I think that one of the best parts of being an educator is the various ways the work challenges you to continue engaging with the field. There are very few things that I teach now that are exactly the same as when I was in school: the technology, the critical landscape, ways we view, study and encounter photography is constantly changing. And just in keeping up with the widening scope of what we do as photographers is inspiring and difficult at the same time. I love that the two courses I teach most often are drone photography and black and white darkroom. In one class I have to continually learn new software, regulations and equipment and the other I can learn new variations or adjust small variables for something I’ve studied for twenty years. Similarly, I love that teaching contemporary photography today demands discussion of photobooks in a different way than I would have ten years ago. Which is all to say that for me committing to teach photography requires a level of engagement with new developments in the field that is truly exciting.

ES: Describe a meaningful anecdote(s) that you had with a student.

MK: This is a tough one. I feel like I could fill the question with just stories from those short conversations outside the darkroom looking at a test strip with a student that turn into really interesting dialogs about their work and the print. Those are the best! Or the truly silly times, like this past semester when a drone student lost their aircraft after a bird hit it over an abandoned cement factory that might have involved a little bit of trespassing/bushwhacking and water fording to get the equipment back.

But I think that the most significant stories I have with students come from working with students abroad. I have taken two groups of students to South Africa to work with South African photographers, gallerists, and printmakers. In both instances being able to facilitate meaningful collaborations between my students and those from my South African colleagues was everything I love about teaching. The first year the students partnered with photographers in Durban to create a series based on a topic chosen by their South African counterpart. In responding to a new place, the practice and experience of their partner, and editing the final work together, the students grew in a meaningful way. Working in South Africa has been incredibly meaningful for my career and being able to share that experience in some way with students has been truly special.

ES: What advice would you give to photography students?

MK: The best advice I would give to photographers—aside from trying to get more sleep and drink more water—is to find a way of making that is sustainable and for yourself. I’m at a strange and wonderful place in my career where I am (relatively) recently past tenure and able to step back from chasing everything in the productivity circuit: making work that can get a residency, a show, a portfolio for a job. I’m incredibly privileged in this respect and I absolutely recognize that. And now that I’m here I feel like I’m learning something that I should have a very long time ago: how to make work that isn’t “for something” other than the question of the project itself. I think about this change in relation to my work in Louisiana now. The project I’ve worked on for the past five years and more deeply committed to in the past two isn’t for anything and I honestly don’t know what or how I want it to end up. I’m pretty deeply immersed in thinking about a few different sequences for the work and how I can refine the formal conversation I’m having with the subject matter the more I photograph in the area. But I’m not changing or modeling what I’m doing for a specific end. And the result is that I find myself working in an authentic way that just didn’t feel possible when everything was so uncertain for me professionally. Which is a very long way of saying that I would advise photography students to do what they need to to make the work without expectation. And to be honest with yourself about what that means relative to your own practice.

Thank you Meghan. Your students are very lucky to have you. To follow is a small selection of photographs from three of Meghan’s students.

Ben Levine is a photographer and visual artist from the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles currently based in New York. He holds a Bachelor of Arts from Washington University in St. Louis.

His practice explores what we cherish and the complex ways we engage with art objects and popular media. In addition to his art practice, he currently works as a photographer for Sotheby’s. His photographs have been featured in news outlets around the world, including The Times, artnet, ARTnews, The Boston Globe, and Puck

Website: Benlevine.xyz

IG: @possiblybenjamin

Hamilton Heights” is an ongoing project recording the beginnings and growth of a new friendship of mine with a lovely lady named Ms. Jones. Ms. Jones is a spunky 92-year-old who, for the last year, I’ve spent most Monday and Friday afternoons with. I kind of stumbled into this project. It began as me making photographs of her in her spaces to give to her, but it quickly evolved into much more and is continuing to grow.

Emily Shih

This series of images considers states of mobility; literal, in a physical and cultural sense, metaphorical, and spiritual. Pulling from a close observation of human interaction with the environment as inspiration, particularly in the context of car dependent culture, these images draw relationships between active states of being and the physical and emotional remnants constantly left behind, while threading meaning from my own life and loved ones.

Owen Rokous

Website: rokous.cargo.site

About Meghan

Meghan Kirkwood is an Associate Professor and chair of undergraduate Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. She earned a B.F.A. from Rhode Island School of Design in Photography before completing her M.F.A. in Studio Art at Tulane University and PhD at the University of Florida.

Kirkwood’s work has been exhibited internationally in solo and group shows at venues including Blue Sky Gallery (Portland, OR), Filter Space (Chicago, IL), Bangkok Art and Culture Center (Thailand), ArtSpace Durban (South Africa), Colorado Photographic Arts Center (Denver, CO) Plains Art Museum (Fargo, ND), Greenville Center for the Arts (Greenville, SC), Rosza Gallery (Houghton, MI), and the Humble Arts Foundation.

Her photographs are held in several private and public collections, including the RISD Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, Lewis and Clark University, University of Idaho, Minot State University, North Dakota Museum of Art, and the University of Florida Genetics Institute. Her work has been featured in publications such as Places, Lenscratch, Oxford American, New Landscape Photography, and Landscape Stories. She has also received full funding to participate in artist residencies through the National Parks Service, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Lakeside Lab (Iowa).

In tandem with her studio practice, Kirkwood also researches in the fields of African art and the history of photography. Her writing focuses on the uses of landscape imagery by contemporary South African photographers. Her writing has been published in Lenscratch, Social Dynamics, Exposure, Photography and Culture, Landscape Journal, and Photographies.

Website: www.meghankirkwood.com

IG: @meghan.kirkwood

Elizabeth Stone is a Montana-based visual artist exploring potent themes of memory and time deeply rooted within the ambiguity of photography. Stone’s work has been exhibited and is held in collections including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, AZ, Cassilhaus, Chapel Hill, NC, Yellowstone Art Museum, Billings, MT, Candela Collection, Richmond, VA, Archive 192, NYC, NY and the Nevada Museum of Art Special Collections Library, Reno, NV. Fellowships include Cassilhaus, Ucross Foundation, Willapa Bay AIR, Jentel Arts, the National Park Service and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts through the Montana Fellowship award from the LEAW Foundation. Process drives Stone’s work as she continues to push and pull at the edge of what defines and how we see the photograph.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Lynn Whitney in Conversation with Andrew HershbergerNovember 14th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Josh BirnbaumOctober 10th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Dana FritzSeptember 12th, 2025