On Collaboration: Street Scene by Hans Gindelsberger and Jon Horvath

It seems particularly appropriate to present this collaborative project in a period of quarantine with uncertain timelines. We are all rethinking routines — scrambling to maintain the familiar and readjusting priorities assisted by digital tech-nology.

Street Scene, the ongoing project by Hans Gindelsberger and Jon Horvath, has its origins in shared generational memory, allowing iconic imagery to redirect into the future and transform into a narrative of its own. This project is a reminder that measuring and recording data of time and space is interactive and dynamic. As we readjust our own personal narratives, we’ll find “some complications and awkwardness in the process” — but we will have the opportunity to embrace a number of surprising alternatives.

Street Scene

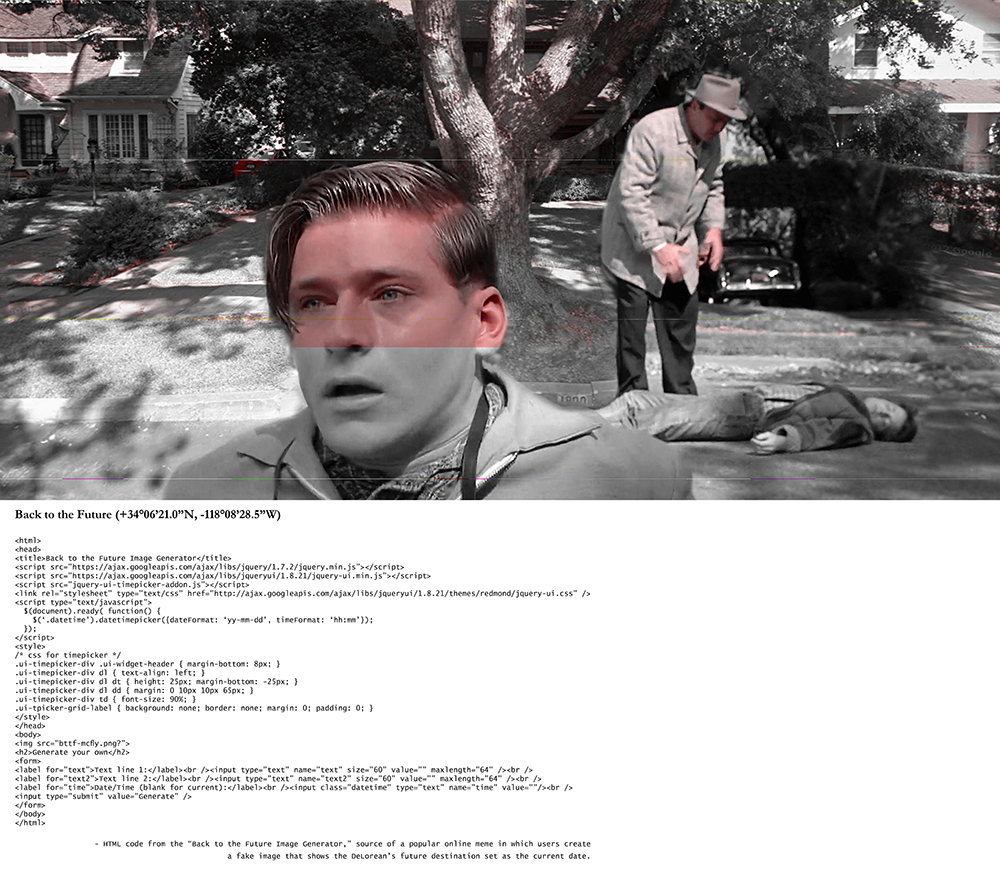

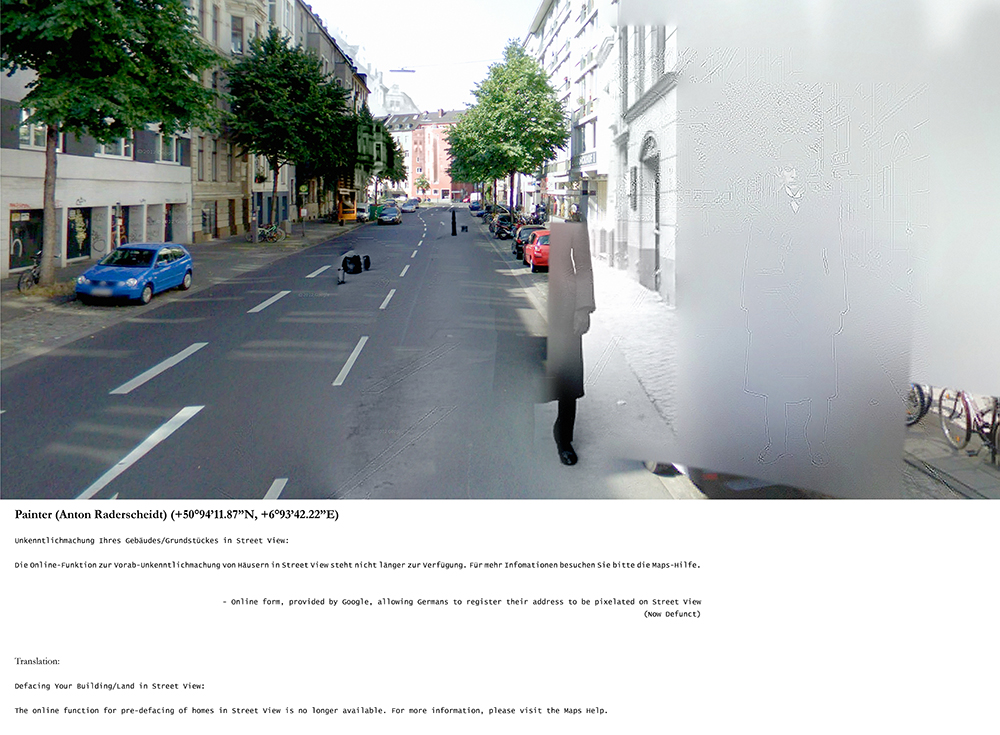

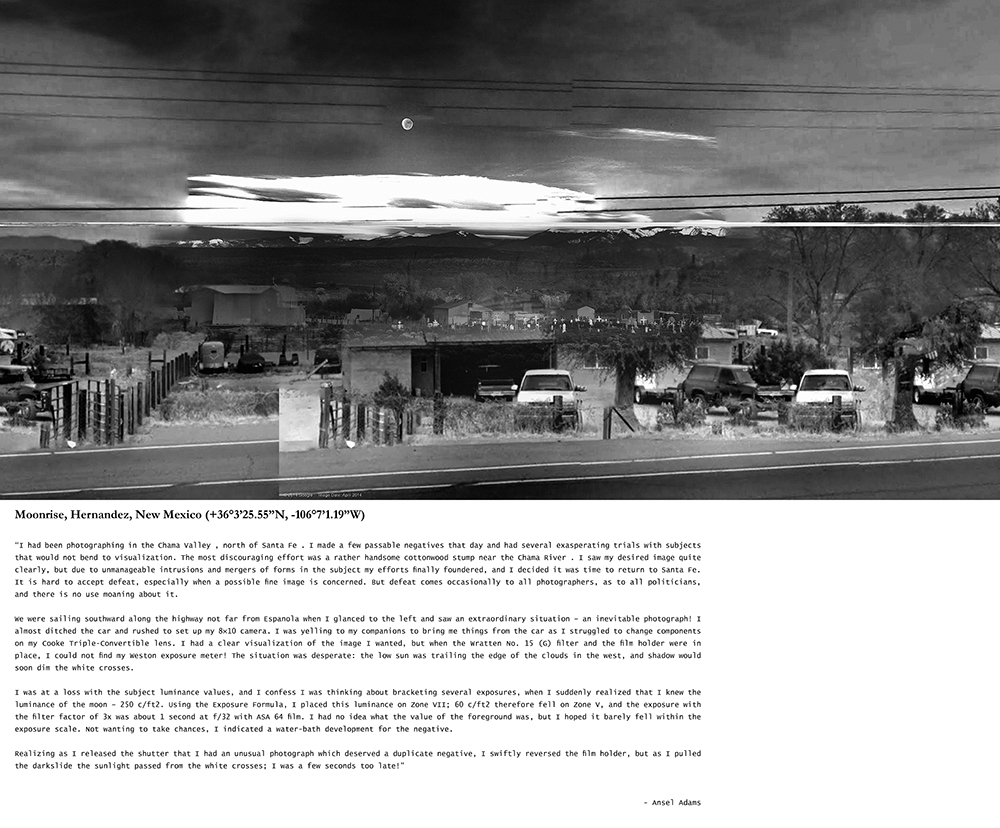

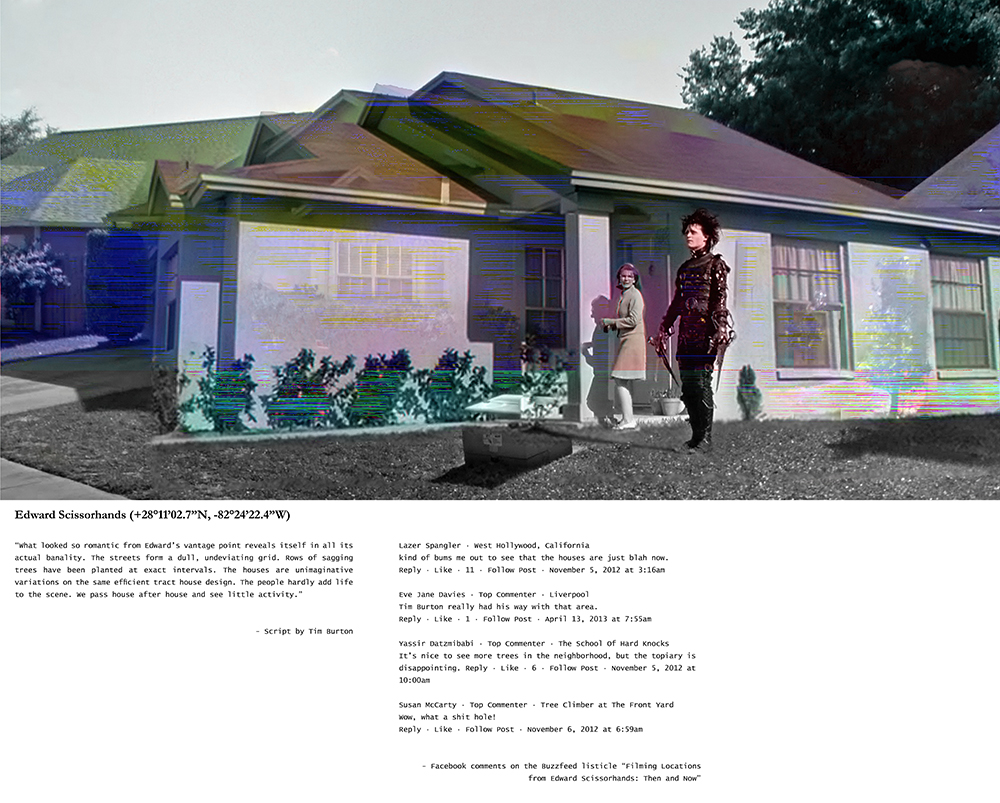

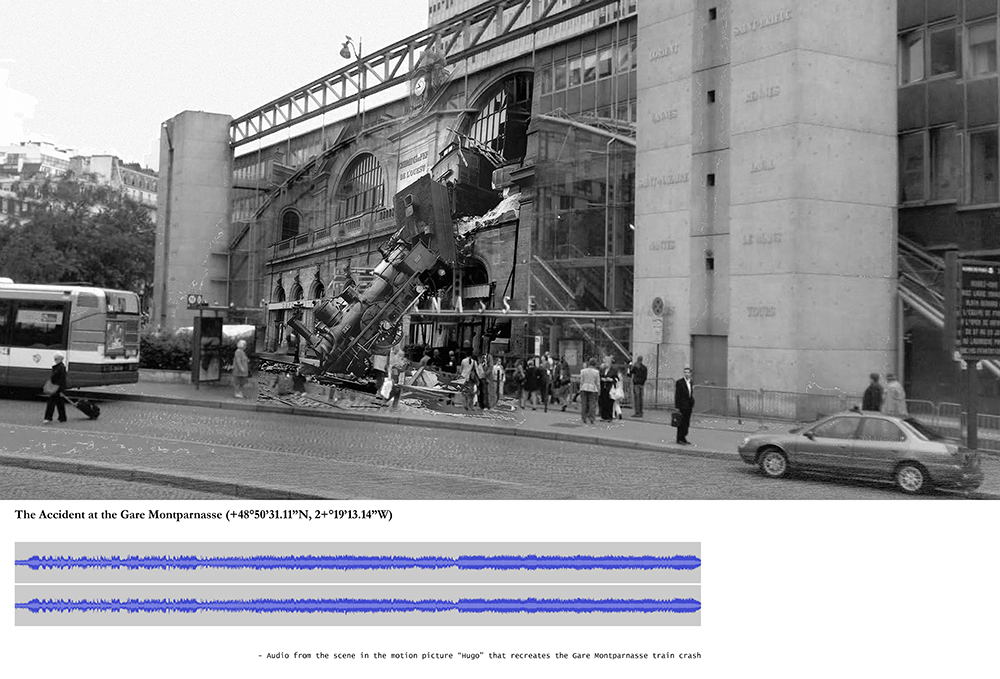

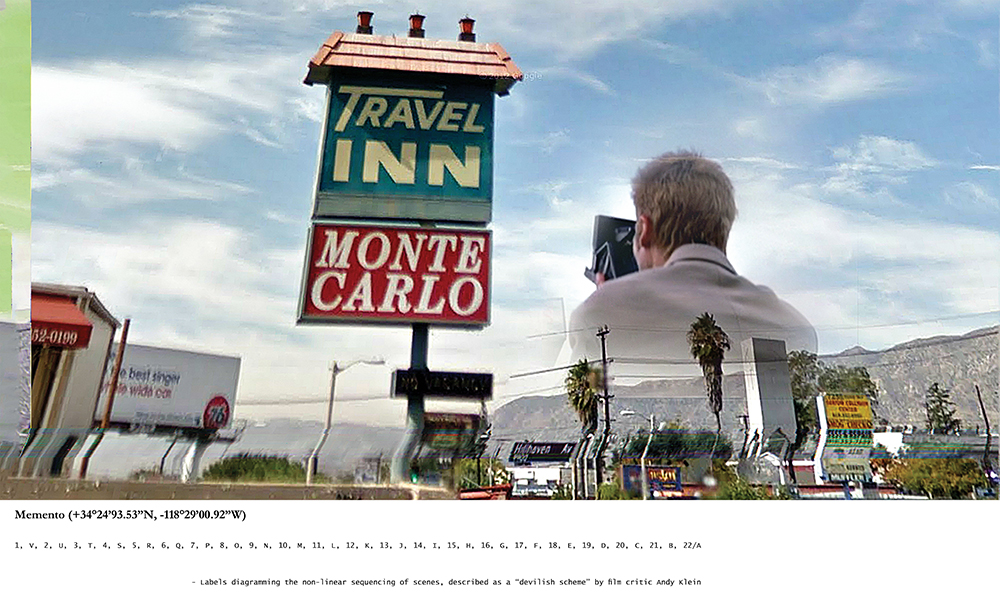

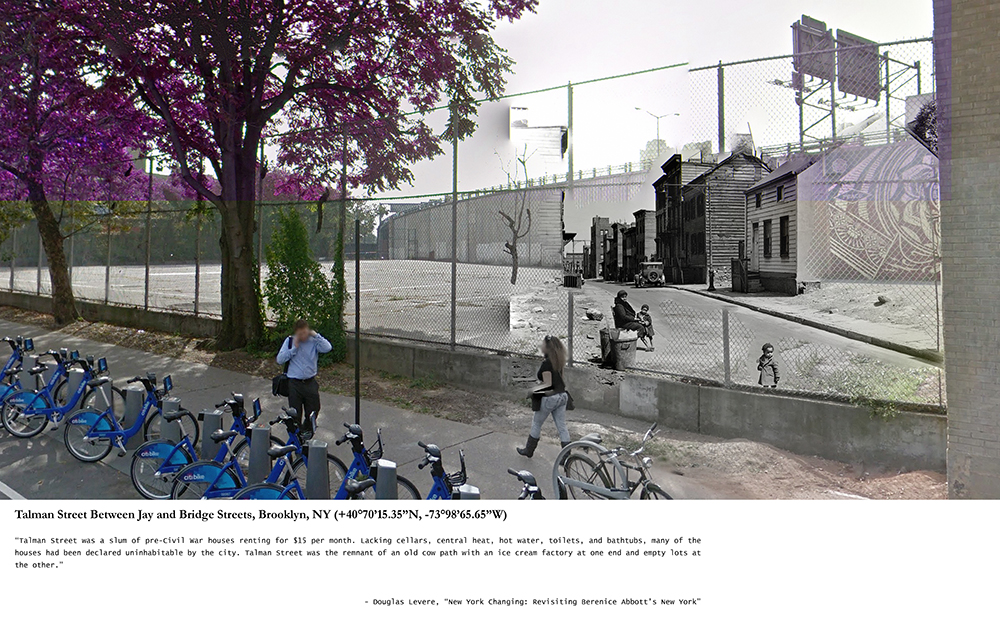

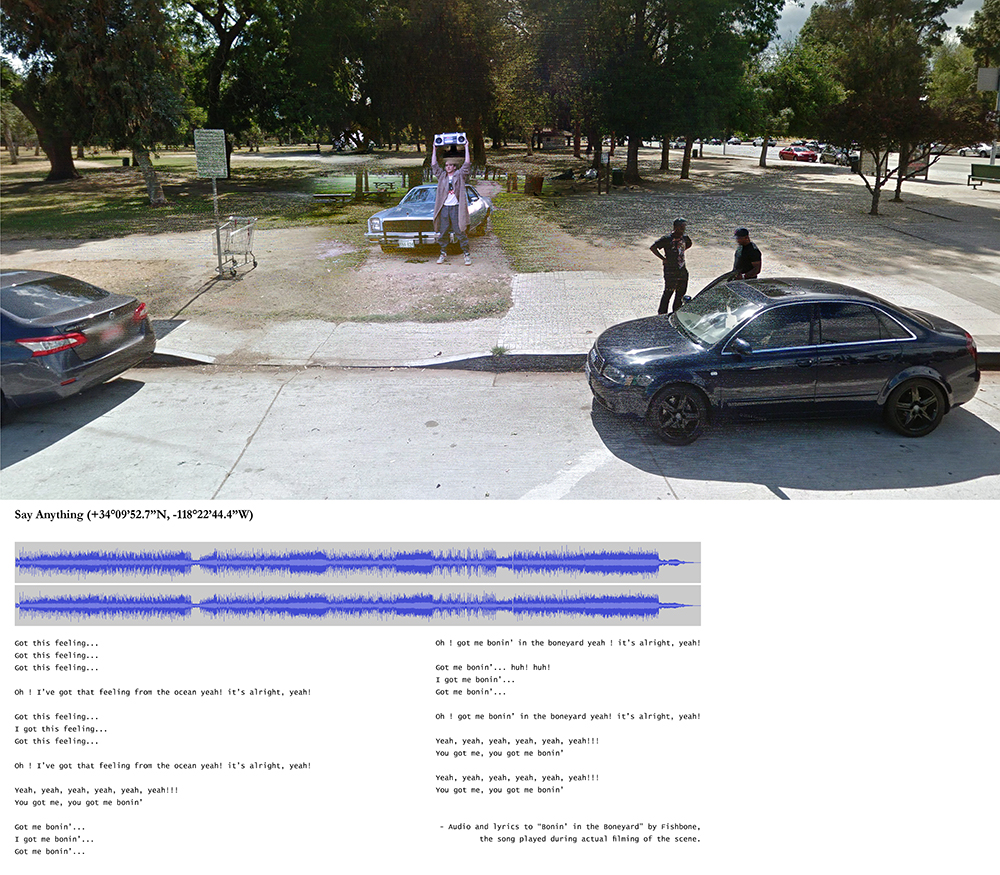

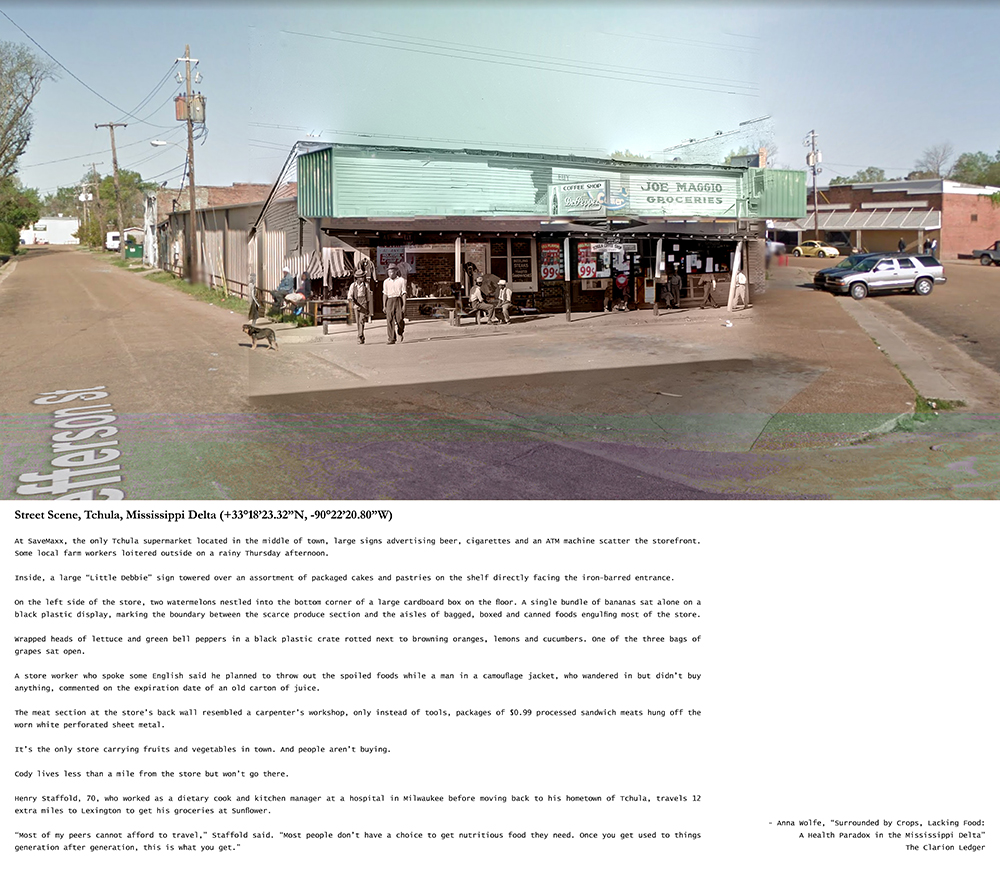

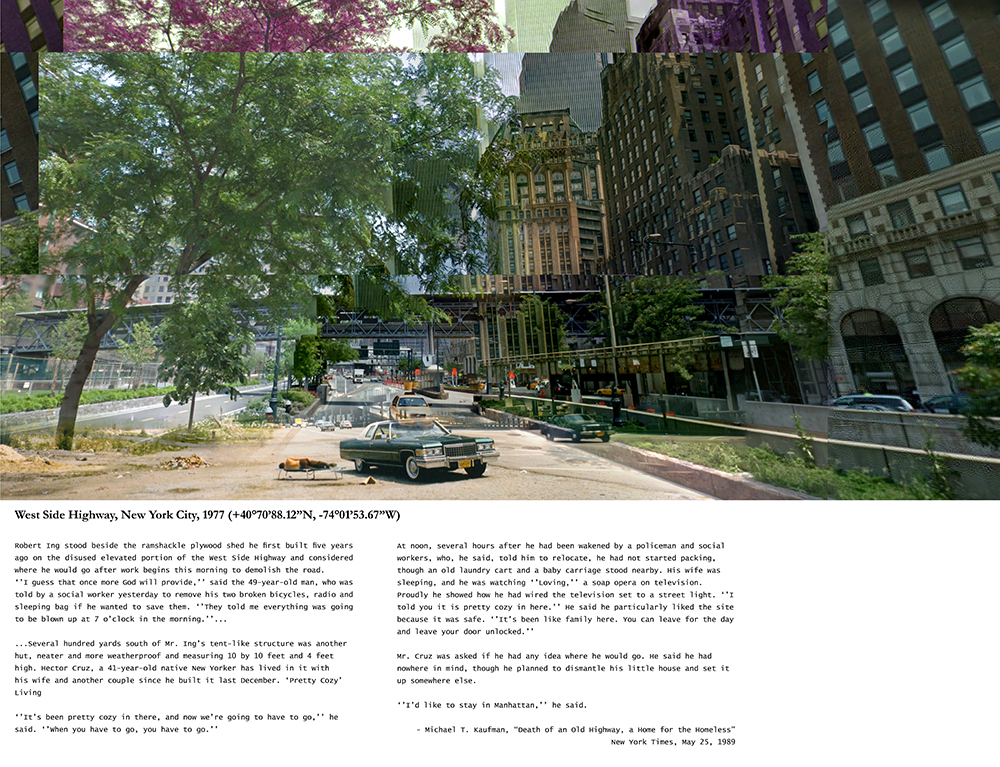

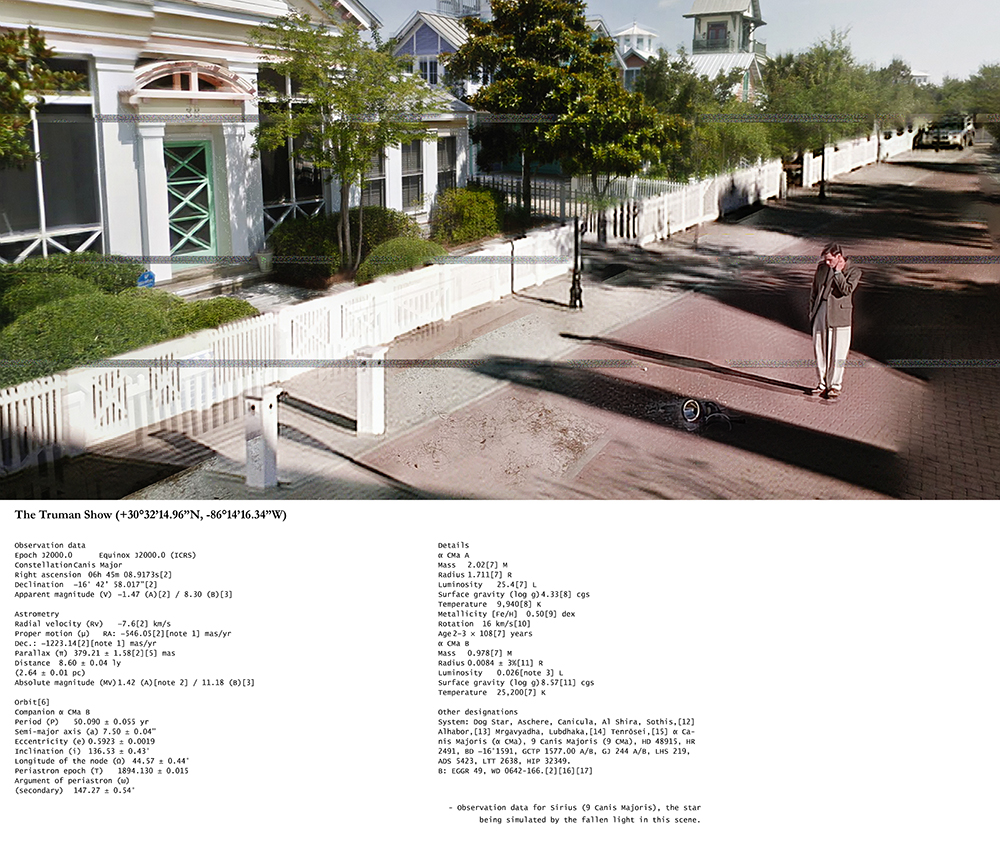

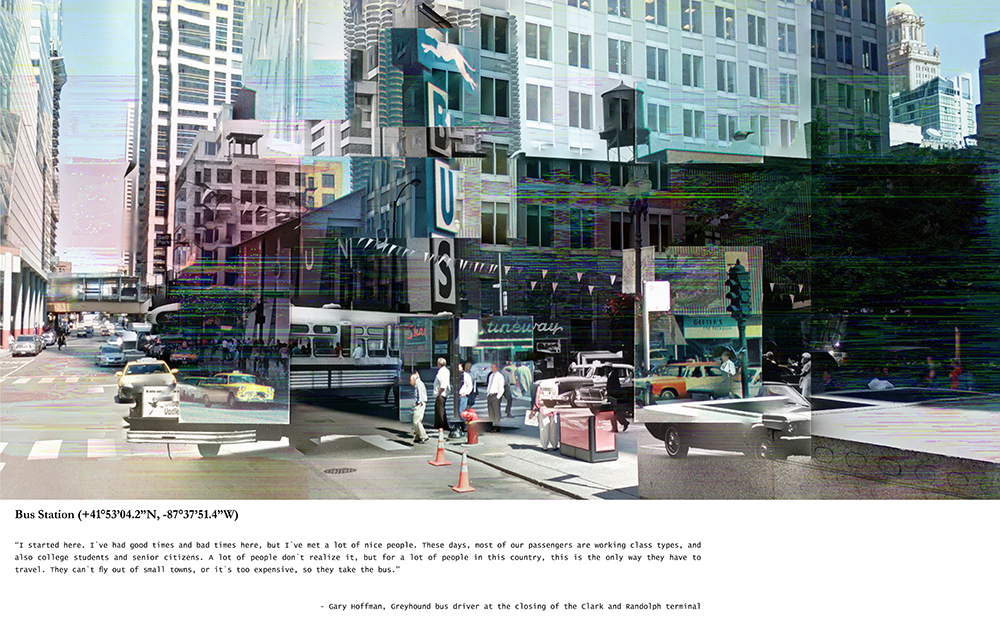

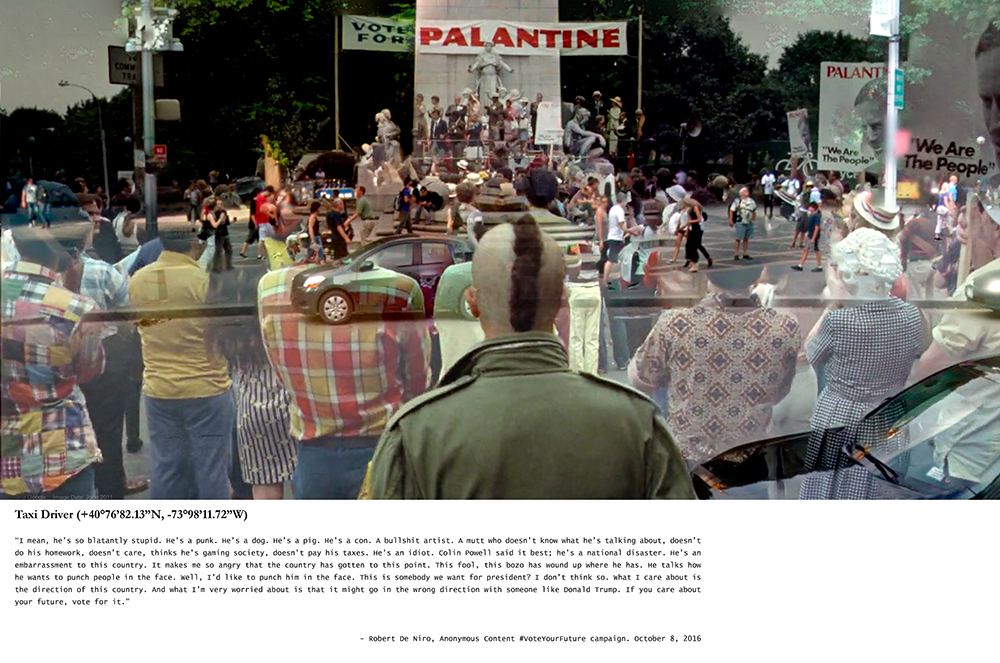

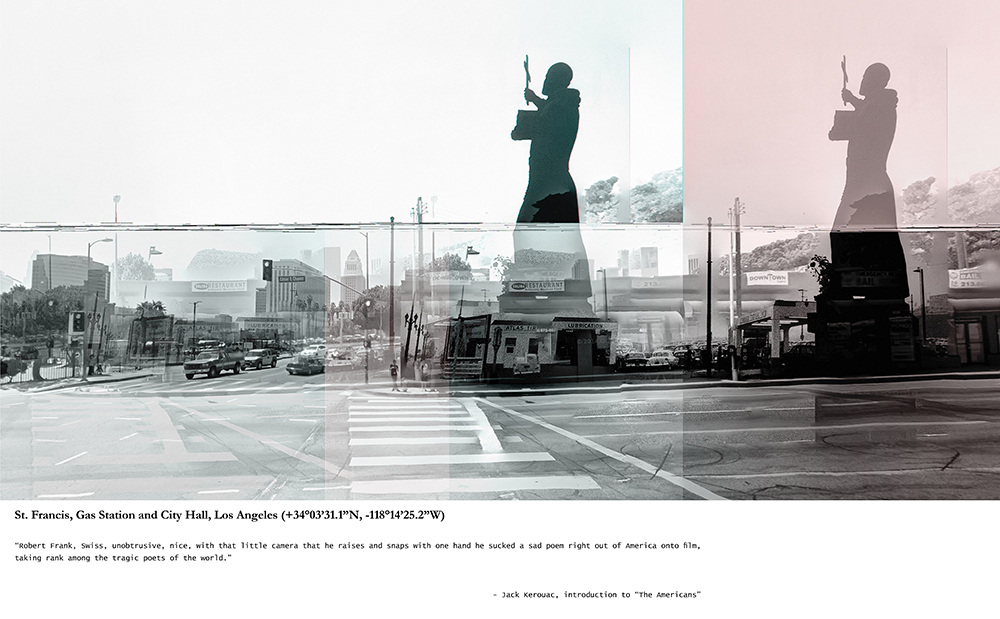

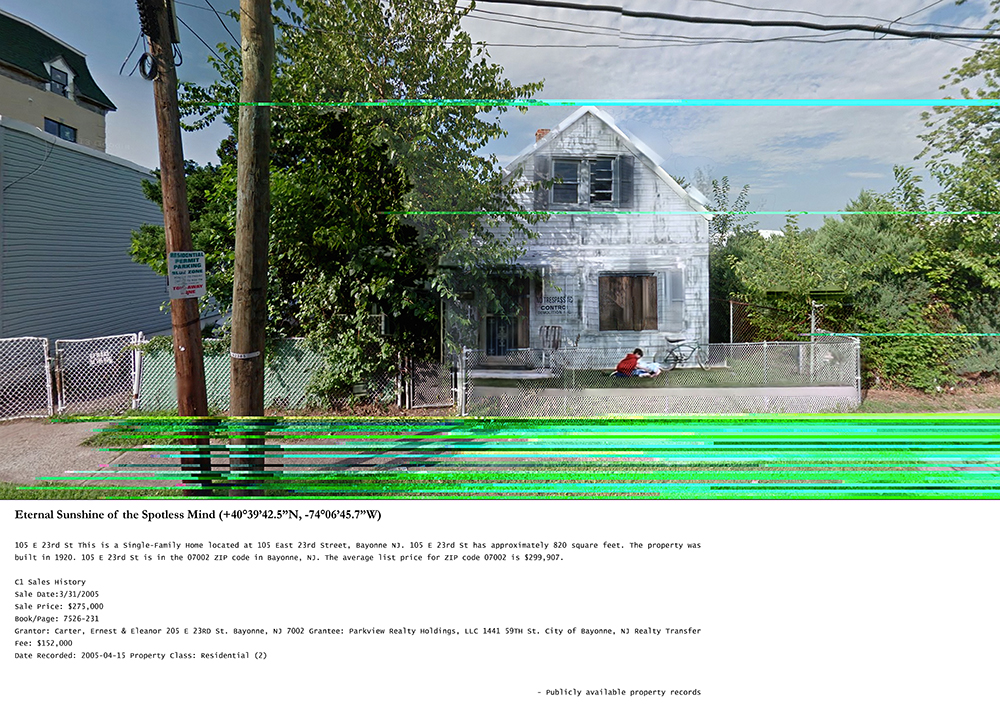

Continuing in the tradition of re-photographic projects, we use the Internet and immersive travel software, such as Google Street View and Bing Streetside, to virtually journey to sites where iconic images from the history of photography and cinema were created. While satisfying a similar impulse, each platform delivers its own unique perception of reality. In choreographing a mashup that offers varied perspectives of a place, we overlay the iconic image with the virtual landscape and then allow an intelligent computer process to determine how those two sets of information will interact and form a new type of image that asks questions about our experience or non-experience of places through the proxy of technology.

Can you describe the initial conversation that generated your collaboration?

For a couple years we were both teaching in the photography program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. A handful of us shared a small office, so it was a space where ideas bounced around and it was easy to come into contact with the work other people were making. Around that time, Jon was working on a project, “Passages,” that used Wisconsin’s alphabetical highway system to spell out passages from Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road.” At the same time, Hans was screen recording in Google Street View a virtual cross-country trek and extracting the simulated movement for his video “Westering.”

Through those projects and other individual works, we were already exploring similar territory, but we also recognized a shared affinity for humor, flawed logic, and romantic gestures in our work. However, we overlapped at UWM for only a short time and the collaboration didn’t actually begin until after we were working in different cities. In some ways, having a bit of distance might have made a collaboration easier to enter into. Of course, there were some complications and awkwardness in the process of trying to give form to an idea over video calls, then later on never being in the same space together to actually make the work. At the start, we both approached a long-distance collaboration with less immediate concern for how it might impact our individual practices and more of a friendly excuse to reconnect and see what would come about if we drove some of these ideas forward together.

We Skyped a couple times a month early on and laid out a range of ideas surrounding the history of street and travel photography, the relationships between photography / cinema / and emerging technologies, and what role virtual spaces play in constructing our sense of memory and consciousness. We took our own interpretations of those conversations back to our separate studios and would start making imagery in response. Gradually, we built toward an initial definition of the project as being about the experience or non-experience of real-world places through media narratives and decided we would visualize that by conflating the different layers of imagery and stories that took place on a single site.

Your first images seem to have been derived from a shared personal sensibility and cultural history. What is your working process…do you work simultaneously or separately on the ideas and images? How do you share information with each other?

Formative experiences with mass media that were shared between us played a big part in directing the early phases of “Street Scene.” The commonalities of growing up in the Midwest in the era of the blockbuster through the advent of the Internet, then having a similar grounding in photo history left us with a lot of the same visual touchstones. So, when we were looking for source material that would engage with a certain idea, often times we would instinctually imagine similar blockbusters or cult films or iconic photographs. It was pretty rare that one of us would suggest source material that the other was unfamiliar with. Early on we decided that the project wouldn’t discriminate when it came to the influence of both “high” and “low” culture. A project that contains both Henri Cartier-Bresson and Edward Scissorhands ends up being reflective of not only our own tastes but also a broader cultural consciousness.

We work together more on the overarching themes and general direction of the project than we do on single images. As we explore more places and generate additional imagery, more and more sub-themes have started to emerge across the project. We tend to talk through the larger issues and once a particular theme is in place we come up with a list of possible source material. That list gets divided up and we each go our own way to research the location and create the image.

Where the project starts to diverge from a personal or shared sensibility is in the process of tracking down the location where the movie or photograph was shot. Some of the more popular movies have a fan culture around them that makes them easy to find, but for others, especially the photographs, we have to search online for little bits of evidence visible in the pictures, which lead to all sorts of anecdotes and information about the location or the background story of the source material. That kind of narrative information is often separate or even contrary to the impression left by the film or photograph. We collect some of that material and both glitch it into the composite image and present it alongside the photograph. We’re trying to cultivate a multilayered understanding of places that grow partially out of lived experience, indirect experience though mediated imagery, and also incorporates outside perspectives and alternative stories.

How do you reach consensus as you proceed? Has your process evolved over time?

Early on we were much more accepting of each other’s personal, nostalgic, and influential preferences. There was seemingly an unending source pool of material we could reference, so in the manner that many projects begin, “Street Scene” started with our own personal experiences and when those experiences overlapped, all the better. That’s probably how a film like “Ghostbusters” found its way into an early edit; equally as funny, horrific, and pleasurable for us to see a mashup of the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man making his way through the arena of Google Street View. The only real debate at that time was over finding the visual sweet spot for the final composited and glitched image.

Pretty quickly, however, we discovered that there was much more sitting beneath the surface of this project than our desire to see a favorite film location invoked. As with anything, when you look closer and through a variety of lenses (political, cultural, economic, historical, etc.), you unearth a new appreciation for the larger narratives that contextualize a subject and this was certainly true of how we came to approach identifying Street Scene sites moving forward. As we became more aware of the deeper history of a site or a film or a photographer or a subject, we became far more intentional and discriminant in what we elected to reference. Often times, a site as it exists today (or in the most up-to-date version of Street View), is far different than how we’ve come to know it through its more popularized moment in time. We’ve witnessed through Street View how communities have changed demographically, economically, physically, ecologically, etc. since the time they were imaged in popular films or photographic history. We’ve unearthed first and third hand historical accounts of those changes, and this is what often enters into our conversation on how to approach glitching or corrupting the image code. So now, the process prioritizes enriching the final “Street Scene” works with layers of both visual and historical information far more, and via our selection of those materials, it allows us to either take a critical position or ask a probing question of a place, and hopefully have our audience join in that conversation. We’ve been able to leave our “favorite” films and photographers behind, and instead attempt to see Street View as an unintended but revelatory tool for how people interact, places evolve, and bias lives within our current popularized technology.

What have you learned from collaborating? Do you have any advice for future collaborators?

Hans: Most of all I’ve appreciated having an opportunity to see how someone else interprets the same material you’re working with and finds meaning, which then influences your own way of thinking and problem solving. It’s been a really interesting working process because “Street Scene” grew out of common interests and shared artistic sensibilities, but I don’t think it’s close to a project either Jon or I would have imagined independently. The collaboration has been a good space to have in terms of my other projects too, because it forces you to break somewhat from your own aesthetic or creative tendencies. Slipping into a different mode of making and thinking usually lets me return to my individual projects with a slightly different perspective that helps to move them forward.

Jon: I think it’s always beneficial to experience things through other people’s positions, methods, standards, etc. Collaboration, for me, is an opportunity to experience both empathy and self-analysis. You learn pretty quickly what you need as an individual, what you’d prefer to be without in your studio practice, what others do that you don’t do (both productive and non-productive for yourself), and the monumental importance of establishing a respectful working dynamic if you want to get anything done. I’ve really come to appreciate the value of clear language, listening, and trying to unearth the things that make people similar. Yes, the work produced matters at some point, but I’d argue that there is a value to the failed collaborative endeavor if it still allows for a moment of revelatory connection to be made.

Fortunately, working with Hans has come with few significant challenges and those challenges have arisen purely from living long-distance, maintaining our own distinct studio practices, and the day-to-day responsibilities of job and family. We’ve been fortunate to avoid any real conflict in vision, desires, or destinations for the work. It probably helps that the project has so many different pathways through it that we can find personal satisfaction in different places when necessary.

What’s upcoming for Street Scene (directions, venues, presentation ideas) ?

We are currently in a mode of deep evaluation, revision, and re-engaging with ‘Street Scene’. A good two-thirds of the project was made in one immersive session over the span of a couple months in 2013. Then, we’ve incrementally contributed new work to the project over the years, often times coinciding with an exhibition, festival, or publication. We’ve had the good fortune to exhibit “Street Scene” in numerous international venues since it launched, but oddly, the two of us haven’t had many occasions to experience the work together in person.

We finally had that opportunity this past year during an exhibition in Milwaukee. We gave a shared artist talk and within the space of that show, new ideas and visions for the project began to crystallize. So, we are excited to now enter into a period with a more sustained approach to shaping the full body of work, likely working in different “chapters” or “categories” of inquiry. We’re still interested in many of the original core ideas of “Street Scene”: the relationship between the real and virtual, the trustworthiness of media and images, the opportunity to navigate the world with emergent and surrogate tools. But we’ve come to be far more fascinated with how those ideas can be put into action in order to reveal a deeper understanding of ourselves; as individuals, communities, citizens, consumers, travelers, as well as the ethics and politics that frame our current technological and cultural moment.

Hans Gindlesberger’s work remains uncommitted to a singular approach or aesthetic, his practice is anchored to an ongoing interest in places, whether real, manufactured, or imaginary, and in playful subversions of the photographic process. Hans received his MFA from State University of New York at Buffalo and is currently Associate Professor at Binghamton University: The State University of New York.

Jon Horvath’s creative process sits at the intersection of new media, photography, and performance. Routinely incorporating concepts of mapping, travel, surveillance, and ritual, his personal lens is often filtered through a subtle humor. Jon received his MFA from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and began teaching photography at MIAD in 2009.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Hillerbrand+Magsamen: nothing is precious, everything is gameOctober 12th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025

-

Christa Blackwood: My History of MenJuly 6th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Researching Long-Term Projects with Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-KilroyMarch 27th, 2025

-

Dodeca Meters: Arielle Rebek, Kareem Michael Worrell, and Lindsay BuchmanFebruary 7th, 2025