Photographers on Photographers: Megan Hansen in Conversation with Jim Naughten

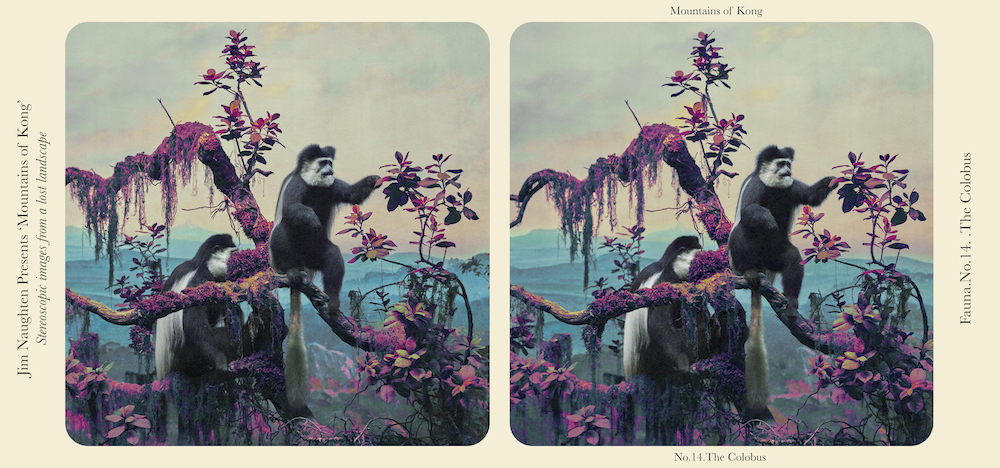

The first monograph I held by Jim Naughten was Animal Kingdom, and it was an experience unlike any I’d had with a photo book before. Included with a stereo viewer, I was transported into the dimensionality of museum specimens featured in the book. It felt like being in a natural history museum while I was sitting at my kitchen table.

Naughten’s most recent work, Eremozoic, has been a constant inspiration and reference point while creating my own imagery. I am compelled by collections, taxidermy, and what I find to be absurd representations of human understanding of mythology, history and experience. Naughten’s represented flora and fauna, preserved in their natural but artificial diorama-habitats with unearthly twists of color, taps into the dichotomy between a love for and a general disconnect to the natural world — a topic I am still grappling with and probably always will be.

Jim Naughten is an artist exploring historical and natural history subject matter using photography, stereoscopy and painting. He was awarded a painting scholarship to Lancing College and later studied photography at the Arts Institute of Bournemouth. Naughten’s work has been widely featured in exhibitions across Europe and the US and including solo shows at the Imperial War Museum, Horniman Museum, and a forthcoming show at the Wellcome Collection (2022), and group shows at the Royal Academy of Art and National Portrait Galleries in London. His first series, ‘Re-enactors’, was published as a monograph in 2009 (Hotshoe Books), his second, ‘Costume and Conflict’, was published by Merrell in March 2013, ‘Animal Kingdom’ was published by Prestel in April 2016, ‘Human Anatomy, by Prestel in 2017 and his most recent, ‘Mountains of Kong’ published by Hoop Editions in 2019 which is available from mountainsofkong.co.uk

Follow Jim Naughten on Instagram: @jimnaughten

Megan Hansen: Your work explores and references history and natural history. What drove you to this particular intersection between history and artwork?

Jim Naughten: I used to paint and draw as a kid. I wasn’t particularly academic, at least not at school so I concentrated on art. I liked certain subjects like archaeology and natural history, and dinosaurs and also built model tanks and aircraft. As an adult I explored some of these themes and discovered a passion for history and reading. It has been fun revisiting them as an artist and reanimating historical themes.

MH: What is your relationship to history as an artist?

JN: I think history is fascinating so it’s really a chance to indulge myself and I do end up learning a great deal. The last three or four projects have been created with museum collections which is extremely enjoyable, working outside of museum hours with inanimate objects (much easier to photograph too :).

MH: What does finding inspiration and researching for projects look like to you?

JN: Right now I’m in a lull. It’s slightly scary waiting for the next project to appear or present itself. So up until recently my ideas have come from books, often history or natural history, but the last one, Eremozoic is a very different beast. It’s an activist piece in which I’m hoping to raise awareness of the biodiversity crisis and mass extinctions: I learnt about the scale on a trip to the Field Museum in Chicago and was horrified. I decided then and there I had to make some work that addresses the subject.

MH: Where do you find inspiration both inside and out of the artworld?

JN: Usually it’s not from the art world. I try to just concentrate on what interests me, not usually art. So mostly it’s a subject that I feel compelled to make art about. That can come from anything, books, museums, film, history.

MH: Your monograph, Animal Kingdom, is one of the most unique photo book experiences I’ve come across, included with a stereo viewer to view the stereographic imagery. What brought you to this method of image making and why was this type of viewer experience important to you?

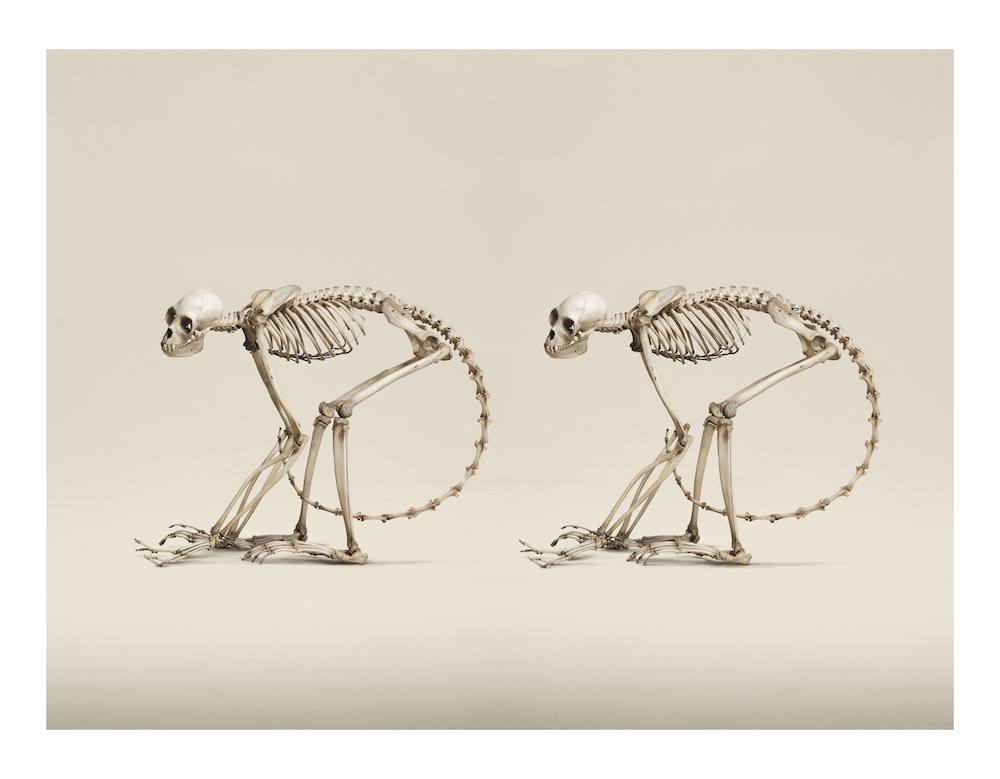

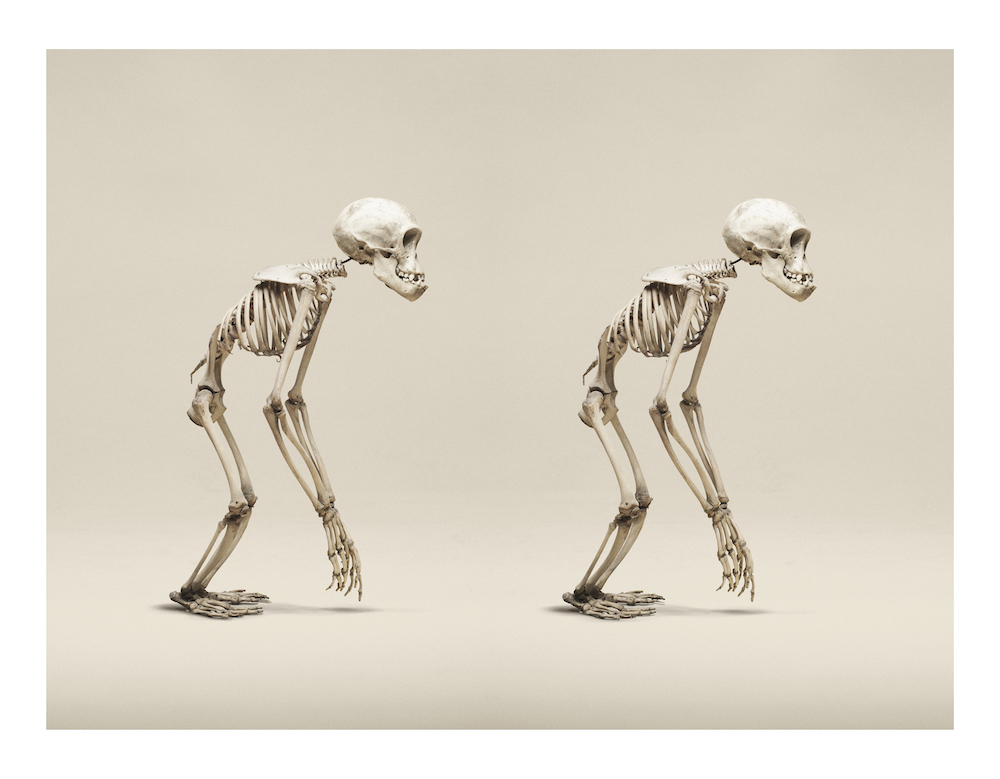

JN: I was researching a project on the First World War and stumbled across stereo cards from trench warfare. I bought some, and a stereo viewer and ‘boom’ ! It was incredible. It’s hard to describe but there’s a real sense of being transported back to the time the image was taken and an intimacy that you don’t get with a two dimensional image. I wanted to find a subject that would suit the medium and felt natural history would be perfect. It’s also a subject I love. The specimens were (and still are) studied by generations of zoologists in comparative anatomy and there’s a real connection with studying the specimens in detail with the viewer.

MH: Animal Kingdom utilizes collections and archives. What is your relationship to the archive?

JN: I loved Natural History Museums as a kid. Seeing Dippy (Diplodocus fossil replica) in the NHM in London was electrifying. I still love them but see them in more historical terms these days. With Animal Kingdom I wanted to try out my newly discovered (but very old) technology and make a series of stereoscopic images. I often work in typology so creating a series and organising them into type or taxonomy was very appealing. It was interesting to ‘collect’ images from a collection, and arrange and rearrange them. Working in the museums when they were closed to the public was also a privilege and an extremely peaceful experience. It felt like being in a cathedral to the natural world, in quiet contemplation.

MH: Do you have your own collections related to your artistic practice?

JN: Only the images I collect, and perhaps some miniature dinosaurs

MH: Along with stereoscopy, your photographic images utilize painting. How did you arrive at the intersection between different media?

JN: I used to paint when I was younger, and only really stopped at art school as I thought it would be a good idea to learn how to use a camera. I also thought it would be a lot easier than painting, just pressing a button. So in that sense I see myself as a lazy painter. I’ve realised over time that my photographs are all very staged and worked on and actually I really want to get back to painting but it’s a long slow arc to get there. Working with post production methods is similar to using oil as I revisit and alter images over days and weeks, never knowing quite when to stop. I work with brushes and layers so I think of it as digital painting, without the mess. I’ve recently picked up real brushes again so watch this space.

MH: I’m curious about the transition/relationship between Animal Kingdom and later works including Mountain of Kong and Eremozoic that utilize dioramas. How did that transition come about?

JN: With Animal Kingdom and Human Anatomy I was working with individual specimens on a plain background, and they were my first foray into working with stereoscopy and museum collections. When I heard the story of the Mountains of Kong (a mountain range that people believed existed for 100 years before they were discovered to be non existent) I decided to make an imaginary journey using the technology that was in use at the time of the Mountain range ‘existed’ (in people’s minds at least). Scientific expeditions often had photographers so my first idea was to make stereo images of everything, flora, fauna, landscapes, strange mountain tribes and so on. In the end the dioramas worked so well I just used them on their own. I have a paradoxical relationship with them: I love them, but find it difficult to think the animals were killed to order. It was good to reanimate them for this project though.

MH: Eremozoic seems to connect with the past while also tapping into our current disconnect with wildlife and nature. How do you grapple with past, present and future in your imagery?

JN: Eremozoic came about during a visit to the Field museum in Chicago for a different project altogether. As a long suffering Guardian reader I was painfully aware of the climate crisis and mass extinctions happening across the planet due to human activity. The museum was full to capacity but there was a temporary exhibition on extinction without a single visitor. Everyone was more interested in T Rex and the animals that have been extinct for 66 million years. No interest in the ones we are destroying now. I felt I had to make work to address this and it would have to be very colourful and engaging to lure in my audience before I explained what the project was about. The images were in my mind almost immediately. I think all my work has to come from an environmental or activist viewpoint from now on, as the urgency is so extreme.

MH: What is your process like when working on a multimedia project such as Eremozoic?

JN: I work with museum specimens and dioramas so it was a case of trying to find them in the various natural history museums, securing permission to make and use the images, making the images (usually when the museums are closed) and then editing and of course photoshop. This can take a long time. Sometimes I’ll find the images quickly and other times they may sit on a hard drive for months before I notice I have the makings of, or elements of an image. Some need a little work and some need a great deal. Orangutans went through 15 different colour schemes before I realised the jungle should be blue!

MH: Several of your works have been published as monographs. What is that process like for you in terms of editing and sequencing?

JN: I have had publishers use editors to sequence before, and I really like that process of having other creative minds involved. If I do it myself it’s fairly intuitive, just a feeling of how things flow. I will make paper print outs and physically sequence the order by hand, to see how it works and how the images work next to each other.

MH: You also exhibit large scale prints for exhibition. How important is scale to you, and do you prefer one viewing experience over the other?

JN: Showing the work in exhibition form has always been the main motivation for making the work. Back at college we had a ‘wall of fame’ where the best work was exhibited. That always stuck with me. Printed work at the right scale has a definite effect which is almost always lost online. Books and catalogues are a little better but ultimately prints are the way to go. For now at least!

MH: Do you have any advice for young photographers and artists beginning their careers?

JN: Where there is a will there is a way. I know it’s competitive and difficult to make a living from but I would urge people to try and make the work regardless. Make the work for yourself and ignore the audience as much as possible (whilst making the work at least). Imagine you have a gallery with blank walls to fill and you will be the only person to see the work. We had a lecturer at art school who said there are far too many photographs in the world already: Don’t add to the pile unless you are going to make something really interesting!

Megan Hansen is a photographic artist currently residing in Billings, MT. She has a BA in Film and Photography with a minor in Art History from Montana State University, and an MFA from Central Washington University. Influenced by her experiences growing up in the West, she creates work that speaks to individual and geographic identity, using a variety of photographic based medias, including small, medium, and instant format film, digital photographs, found imagery, installation, and bookmaking.

Follow Megan Hansen on Instagram: @meganh.6

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Mehrdad Mirzaie in Conversation with Liz CohenSeptember 4th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Elizabeth Hopkins in Conversation with Nicholas MuellnerAugust 21st, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Cléo Sương Mai Richez in Conversation with Shala MillerAugust 20th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Emma Ressel in Conversation with Tanya MarcuseAugust 19th, 2025