Ci Demi: Unutursan Darılmam (No Offence If You Forget)

Lenscratch recently held its annual(-ish) call-for-projects, and the response was impressive. In total, there were over 500 submissions. We are eager to look through each of these entries and share some highlights over the months to come. Today I am in conversation with Ci Demi about his project Unutursan Darılmam (No Offence If You Forget).

Ci Demi (1986, Istanbul) studied Italian Language and Literature at Istanbul University. He was introduced to visual storytelling at the age of 28. His photographs have appeared in distinguished publications such as Foam Magazine and the British Journal of Photography. His works have been exhibited in many prestigious festivals and art venues such as Les Rencontres d’Arles abroad and Pera Museum in Turkey. In 2022, he was chosen as the winner of the Discovery Awards at the Encontros da Imagem photography festival with his story “Unutursan Darılmam” (No Offence If You Forget, 2018 – 2023). His first photobook “Şehir Fikri” (Notion of a City) was published by Onagöre. He lives in Istanbul and shoots stories for international publications such as The New York Times, Der Spiegel, Die Zeit, Financial Times, Society, among others.

Instagram: @ci_demi

Unutursan Darılmam (No Offence If You Forget)

Everything in this story unfolds within an apartment in Istanbul.

Backstory: In 2019, the author experienced a severe depressive episode, confining him to his home for an entire year. His only outings were for psychiatrist visits and brief trips to the city centre. As months of isolation passed, the city became a distant memory, morphing into a monstrous, ever-changing entity. The photographer clung to the few photographs he could take, dedicating every waking moment to studying, editing, sorting, and writing about them. The episode would last until 2022.

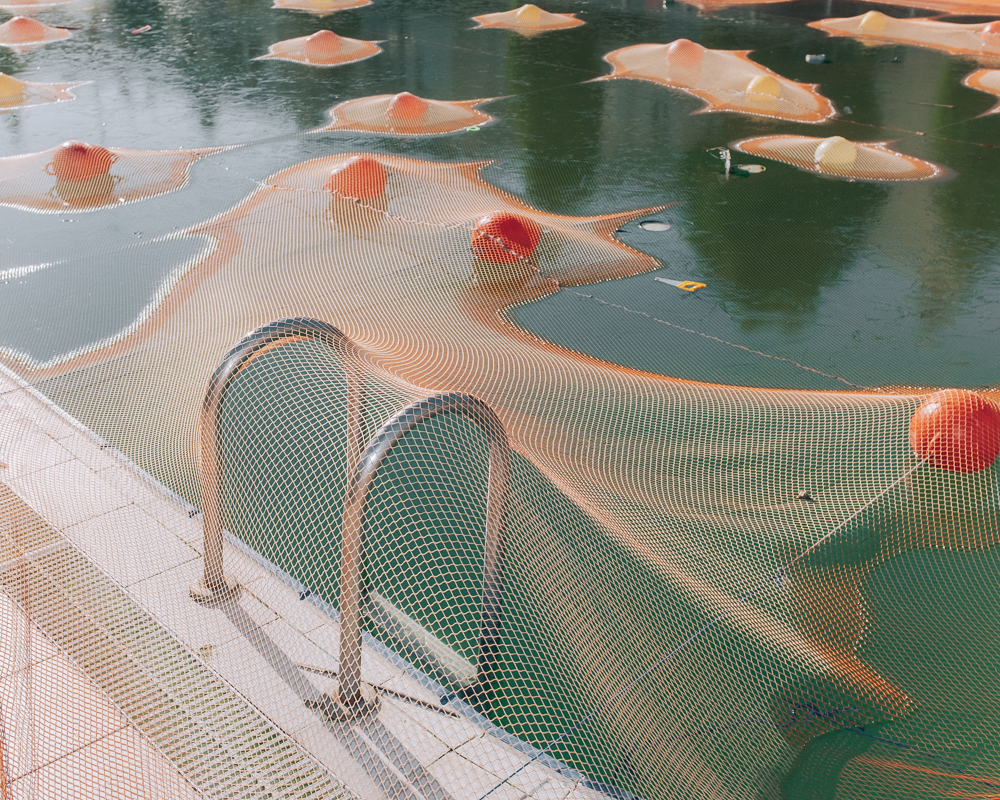

Society often views mental health as a personal struggle, with alienation as a common consequence. This work, however, externalises the author’s battles, reflecting the impact of a newly diagnosed bipolar disorder on various facets of Istanbul.

The photographs capture both everyday life in Istanbul and the emotions these moments evoke in the photographer, offering a glimpse into a heavily medicated mind. The scenes depicted are serene, occasionally chilling, often restless, yet oddly loving.

Navigating a city of 16 million while grappling with a mental disorder: Through photographs, we come to understand that the vocabulary of existing in a crowded metropolis and the inner turmoil of a somber individual share many similarities. One might even say they speak the same language. Photography becomes their silent dialogue and poignant acknowledgment of a single, certain truth: Perhaps it was time to leave.A central question emerges: Who is being forgotten—the photographer or the city? Through photography, this body of work creates a shared memory for both the author and the city—a collection of images to revisit once the struggle subsides.

The project spanned several years, becoming the author’s lifeline for engaging with life and documenting the city’s ongoing transformations. Although the city’s evolution remained relentless, the story yearned for closure. Hadn’t the photographer already satisfied his curiosity or compensated for lost time?

As it turns out, the answer lay in a journey to New Zealand in 2023, for the purpose of settling in the country. There, a lonely scene of a tree in a cemetery triggered a flashback to the photograph of the author’s grandmother’s funeral. One thought bubble later, a conclusion emerged: death looked the same everywhere, even “at the end of the world.”

The photographer decided not to leave Istanbul behind, but to live there as long as it was allowed.

Daniel George: Tell us more about how this work began. At what point in your isolation did you feel it was necessary to do something? Or in this instance, make photographs?

Ci Demi: At that time, the urge to make photographs was pretty much the only thing connecting me to life. Even when I was depressed, I knew I had to cling to something, anything, to pull myself out. Photography was there to keep that connection alive. As a photographer, perhaps instinctively, I saw this as an opportunity to create a short story—I decided on the series’ title in 2019 while considering the scope of the story. At the time, I didn’t know my isolation would last a year, and my depression three. In the end, I documented the city for this project over six years because it evolved into something more.

DG: I am always interested in how creative practice can help in situations of distress or affliction—in your case, a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Would you expand on what you feel photography offered you?

CD: For me, photography is about being present: creating undeniable proof that I was somewhere, feeling those emotions, and taking the photograph. This purpose has never changed; I simply had to keep photographing, hoping something meaningful would eventually emerge. Photography compels you—forces you—to reflect, which played a healing role in my life. Looking at recent photographs allowed me to process how I felt; it became therapeutic to observe, write about, and sequence those images as I captured them. Photography also gives you control; by documenting something—in this case, the early days of a diagnosis through scenes of my city—you gain the power to shape your own narrative. With each photo, I began moving forward, away from the illness.

DG: This work very much feels like you’re considering the relationship you have with your city, which is affirmed by the questions you ask toward the end of your artist statement. While making this work, what did you uncover in terms of your relationship to that place?

CD: At the time, I thought leaving Istanbul would help me leave everything wrong in my life behind—I held onto this idea for five years. When I finally left the city, intending to settle in a new country, reality hit me immediately: nothing had changed. I was the same person; I still had to take eight pills a day, I still had to walk long distances to take my photographs, and I still had to keep creating stories just to feel like I existed (this remains true today). I’ll spare you the ifs and buts: Istanbul is an awful city to live in. If you’re a tourist, hopping on a plane back to your own reality in three days, it can be a wild, fun ride. But when you belong here, it comes with a heavy baggage you can never fully unload. Yet… I realised my story in this city hadn’t ended.

DG: I read on your website that you considered leaving Istanbul to live elsewhere, but ultimately decided to stay. This decision was informed by a memory of your grandmother’s funeral. The theme of memory and place is something I think about when viewing your photographs. Why do you suppose it is important for you to maintain/preserve memory as it relates to place?

CD: I always say this: death is the same everywhere. I don’t attach a grand meaning to it. I love my life, having worked so hard to take back control of it, and I’m not looking forward to death; yet, I’m not exactly afraid of it either. Sergey Yesenin wrote this in the poem right before he took his own life:

“Goodbye: no handshake to endure.

Let’s have no sadness—furrowed brow.

There’s nothing new in dying now

Though living is no newer.”

I remember reading this in middle school and memorising it instantly. I’ve carried these words with me all my life. When I saw that massive tree in the middle of a cemetery in New Zealand, memories about life and death and everything in between flooded in. I realised I didn’t belong in that cemetery, so impossibly far from my city.

Perhaps I won’t always be here; I’ll keep travelling to find other stories. But I have a feeling I’ll end up dying in Istanbul. No one can know or plan this, of course—it’s just something that feels ‘fitting.’ So, here I am, living my life, getting assignments mostly because I’m in Istanbul all the time, still photographing the city, and so on.

Returning was a deeply existential decision, especially for me—a photographer.

DG: This work is currently ongoing, but you have plans to publish soon. Is there anything that you’d like to share about the upcoming book?

CD: We’re currently editing and sequencing the photographs and designing the book with a publisher. Each day brings new discoveries about the story, and I’m in love with the process of making a book. We’re aiming for a launch in early spring 2025.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026