Christine Lenzen: Forever a Wilderness

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Forever a Wilderness, by Christine Lenzen.

Forever a Wilderness

The ongoing series Forever a Wilderness was born from my desire to create a visual mythos of the Great Lakes’ north woods culture – particularly for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Often left off maps of the United States, the Upper Peninsula stretches across almost the entire southern shore of Lake Superior, and contains almost a third of the land mass in Michigan, but with only three percent of its population. While the Upper Peninsula is geographically in the Midwest, the culture and landscape here is markedly different than the traits that are typically associated with the rest of middle America: instead of mile after mile of flat farmland, we have 8.8 million acres of forest; instead of a tornado season, we have blizzards and effectively seven months of winter; instead of a claim to the world’s largest ball of twine, we have Lake Superior, the world’s largest freshwater lake.

The Upper Peninsula is isolated and remote – the first Governor of Michigan once described the area as a “sterile region… destined by soil and climate to remain forever a wilderness.” The residents of the U.P. (colloquially called Yoopers) might be described as walking contradictions as they tend toward hearty individualism – nonconformist and self-reliant – but are also fiercely supportive of their communities with an incredibly strong sense of regional pride. It is the sparsity of population combined with the severity of our winters that elicit these characteristics of Yooper culture. Similar to how place can become intrinsically important to understanding the psychologies of characters in great literature, these photographs echo the sensibilities of this region and its people. While this work is perhaps an ode to my love affair with the Upper Peninsula, it is also a portrait of what much of rural America embodies: pride in our wilderness, commitment to our communities, and the ability to forge through tough times.

Daniel George: What was your first impression of the Upper Peninsula? Was there something other than convenience that prompted your interest in exploring the area photographically?

Christine Lenzen: It actually took me about six years to seriously consider the Upper Peninsula as a subject for a body of work after moving here. I suppose that I first started to conceptualize this work shortly after the 2016 election. Since the election there has been an ongoing national discussion about rural America and the seeming disparity of values between those living in Small Town, USA and the more urban cultural centers of our nation. It has become easy to blame “the other” for all the discord in our country and I found myself in the middle of this conversation – I had always considered myself a “city girl,” but here I was calling my home a small town in the Upper Peninsula.

At the same time, my husband – a Yooper by birth – and I were having a lot of discussions about the role of place in literature, and how our understanding of our nation’s cultural differences is grounded in stereotypes that are perpetuated through various channels of popular culture. He is an avid reader and a favorite genre of his is southern noir novels – and specifically novels set in Appalachia. Popular culture has taught us that this area of the country is full of poor and uneducated rednecks, hicks, and hillbillies – all signifiers used to disparage the people of that region, and allowing the rest of the country to dismiss their concerns as uninformed or the struggles that they endure as deserved. There are a lot of great current authors who call Appalachia home, such as David Joy and Silas House, who are challenging this understanding of their region through their writing and giving a humanity back to the people of their communities. What I recognized in their novels is that they could easily be stories about the Upper Peninsula as there are many shared hardships, such as loss of industry, as well as many shared values such as unwavering support of our neighbors. So, while this is not an overtly political project, we are living in an era of great cultural and political divide in our country. And while the project is certainly about the Upper Peninsula, I also see it as a project about rural America. My hope is that work such as Forever a Wilderness can help spark recognition of the humanity in our fellow Americans.

DG: I am from Nebraska and my wife is from Michigan, so I have this fascination with our states being lumped into the Midwest region—despite enormous geographic and cultural differences. How is the U.P. unique, even when compared to your upper Midwestern home state of Minnesota?

CL: Honestly, in respect to the geography, the climate, and the history – Northern Minnesota, the Upper Peninsula, and even Northern Wisconsin are quite similar: a long history of mining and logging, deep ties to Ojibwe culture as the original inhabitants of the land, strong ties to Scandinavian culture as early settlers, brutal winters with the reward of mild summers, millions of acres of forest, the largest freshwater lake in the world – and no major metropolitan area for hundreds of miles.

One thing that does set the U.P. apart, however, is that we are literally separated from the rest of our state – so much so that one of Michigan’s nicknames, “The Mitten,” leaves us out. On maps of the country we are often combined with Wisconsin, given to Canada, confused for Lake Superior, or just completely left off. When people talk about Northern Michigan, they are usually thinking about the northern half of the lower peninsula. I think residents of the U.P. sort of relish in this geographic anonymity – like we have this secret to which the rest of the country is not yet privy. It becomes a sort of inside joke that bonds us when we can laugh at the rest of the country for not knowing what they are missing.

That is starting to change, though, as there has been a national uptick in people that are interested in so-called “adventure vacations” – and over the past several years, the area has seen an increase of recognition for our incredible biking, hiking, paddling, snowmobiling, and camping opportunities. The number of tourists we are seeing in the area has exploded in the last several years. For example, in 2018, Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore saw more than 800,000 visitors in a single year for the first time in its 53-year history. The tourism is definitely good for our economy – but there is certainly another side to that as we are beginning to see some gentrification of the area and unsustainable cost of living increases for locals.

DG: In your artist statement, you mention the strong sense of community among locals, and your photographs are predominantly centered on developed environments. With a project title that strongly alludes to the inhospitable natural component of the region, why have you decided to focus your attention on people?

CL: The title of the project, Forever a Wilderness, is borrowed from a disparaging statement that the first Governor of Michigan made about the Upper Peninsula after the Toledo War, when the U.P. was “gifted” to the state as a sort of consolation prize for Ohio getting the Toledo Strip. He characterized the area as a “sterile region” that was “destined to remain forever a wilderness.” Occasionally, you can pick up on a sense of resentment from Yoopers toward people from the lower peninsula – whom are often referred to as “trolls” because they live below the bridge. This resentment perhaps stems from this time period and is further fueled by being forgotten and left off maps; a sort of backlash to being treated as lesser-than. Mostly, however, I think that Yoopers wear this “otherness” as a badge of honor; there is a sense of pride to being able to thrive in the unhospitable nature of the area. It takes a special kind of perseverance in a person to choose to endure a climate and a remoteness that many people may find totally uninhabitable. I am interested in highlighting that perseverance and the commitment it takes to live here.

DG: Defining something so large in a relatively small edit of photographs seems daunting. Tell me about your image-making and editing process. How did you decide on the most appropriate representation of the region and its inhabitants?

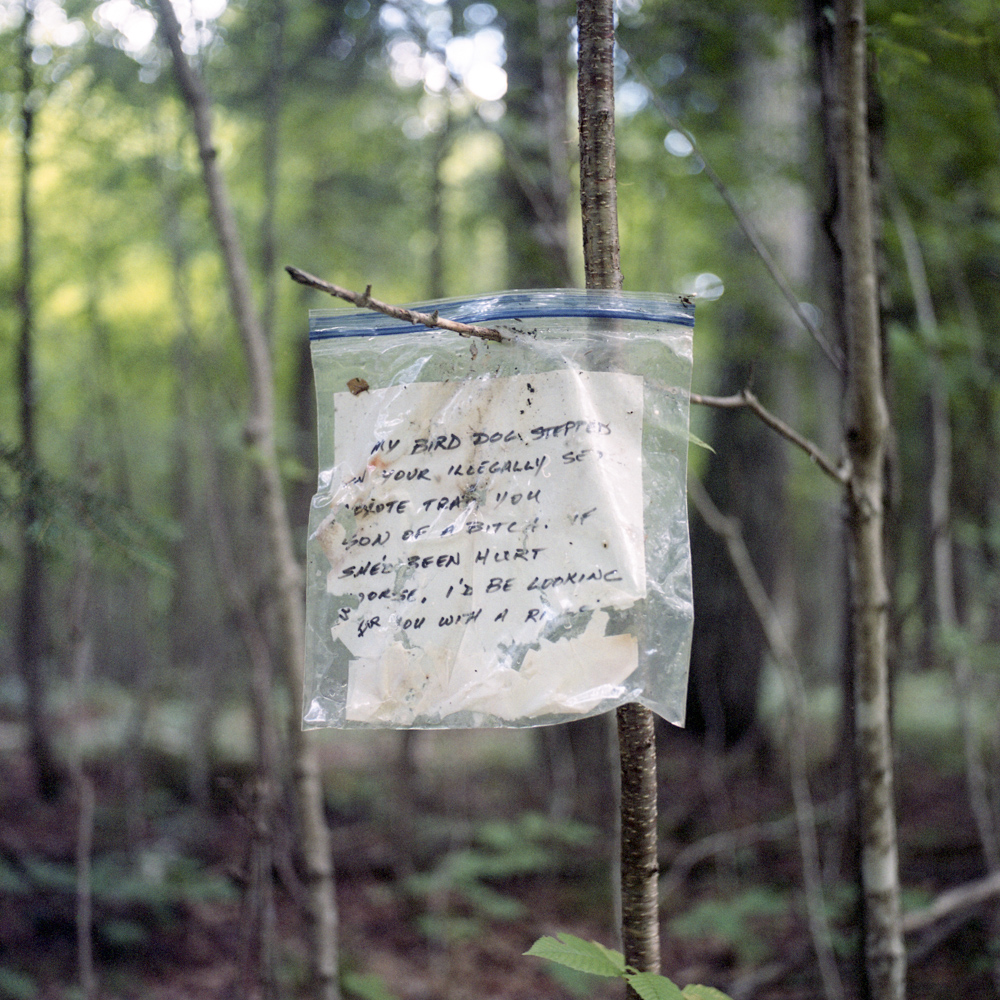

CL: As I noted, I am interested in how some authors use place as an intrinsically important element to helping a reader understand the psychologies of characters within their books. I want these photographs to echo the sensibilities of the Upper Peninsula and the people who live here in a similar way, but I also recognize that I cannot accommodate everything I might want to reference within the work. It felt really important to highlight the loss of industry in the area – so the image of the flooded republic mine felt important to include. The landscape here is littered with abandoned buildings, but including too many references to this within the work felt heavy-handed and somewhat counter to the narrative on which I am attempting to focus. The inclusion of the derelict IGA references not just these abandoned buildings, but also the hardships that small towns are enduring due to changes in the way our culture is handling commerce. It is moments like these, photographs that tell a slightly more nuanced story, that I am looking for when deciding which images belong within the project.

I recently read an interview with Alec Soth in which he mentions that sometimes when editing we have to let go of images that we really love. This rang so true to me. Sometimes our favorite image taken for a project, just does not fit within the larger context of the work: maybe it is repetitive, maybe the compositional elements are fundamentally different than the rest of the images, maybe its content is counter to what you are actually trying to communicate. None of this means that the image is not beautiful, but it might mean that its inclusion would bring down the quality of the work as a whole. This is something that I continually think about when editing this project and certainly something that I am still trying to master.

DG: You also mention that this project is ongoing. Where do you see it progressing, and to what end?

CL: At the moment, I feel like I will never be able complete this project – I am too in love with my subject matter. Practically, however, I have only recently started to focus my images on the portraiture. I am interested in people who have multiple generations of history or unique personal connections to the region, and plan to both photograph and interview my subjects about their relationship with the land or wilderness of the area for use as background information should the work be published. This needs to be a cross section of the community that I thus far do not have: mining families, railroad workers, indigenous peoples, hunters, etc. All of these different people and communities have important yet very different relationships with the land and I think it is important to have more representation of that in the project.

The work is also missing one pretty crucial aspect to understanding life in the U.P. – the harshness and longevity of our winters.

Christine Lenzen (b. 1984 Minneapolis, MN) received her BFA from the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities and her MFA from the University of Notre Dame in 2012. Lenzen is currently an Associate Professor of Photography at Northern Michigan University in Marquette, MI. She was recently shortlisted for a Lucie Foundation Fine Art Scholarship, listed in the Top 200 for Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and received honorable mention for the Julia Margaret Cameron Award for Women Photographers. She has exhibited with the Texas Photographic Society, Houston, TX; Blue Spiral 1 Gallery, Asheville, NC; Southeast Center for Photography, Greenville, SC; The Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO; and Rayko Photo Center, San Francisco, CA.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026