Margo Ovcharenko: Overtime

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

This week on LENSCRATCH guest editor Yana Nosenko brings together the work of four photographers tracing the post-Soviet condition.

We are pleased to present a selection of projects and conversations with Anna Guseva, Margo Ovcharenko, Anastasia Tsayder, and Yulia Spiridonova.

Post Co-op

This exhibition brings together four photographic practices that trace the post-Soviet condition as a lived reality shaped by space, fear, discipline, displacement, and the body. Across landscape, portraiture, and long-term documentary work, these artists examine what remains after systems collapse or harden, when “home” becomes unstable and visibility is negotiated rather than guaranteed.

Soviet microdistricts re-emerge as overgrown Arcadias, where vegetation quietly reclaims utopian architecture and transforms control into unpredictability. The psychological aftermath of the 1990s appears as an inherited inner climate, where violence and instability leave lasting marks on identity. In the closed world of women’s football, queer youth find solidarity and refuge within strict boundaries, while the surrounding environment remains hostile. In exile, immigrant communities form fragile “spaces of appearance,” offering temporary belonging while intensifying the tension between survival and assimilation.

Together, these works speak to endurance under unstable conditions: how people adapt, hide, re-root, and continue. Here, “home” is neither guaranteed nor singular. It is overtaken by plants, haunted by memory, protected by rules, searched for in diaspora, and continually reconstructed, one image at a time. — Yana Nosenko

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

Margo (b. 1989, Krasnodar, Russia), a Kyiv-based artist born in Soviet Russia, currently displaced. She graduated from The Rodchenko Art School in 2011 and Hunter College MFA via the Fulbright scholarship program in 2015. She resided at Fabrica S.P.a. in 2011, Italy. Her work was shortlisted by Aperture for the first photobook award in 2018 and for a portfolio in 2022. In 2019, she was selected for “Body: The Photography Book” by Nathalie Herschdorfer and in 2011 for “reGeneration2—Tomorrow’s Photographers Today” by Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne. Margo, deeply engaged with feminist and queer discourse, has worked with LGBTQ+ subjects for over 14 years in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine. Her projects focus on Soviet and Russian propaganda, sports, queer intimacy, and empowerment through self-expression.

Follow Margo Ovcharenko on Instagram: @margoovcharenko

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

Overtime

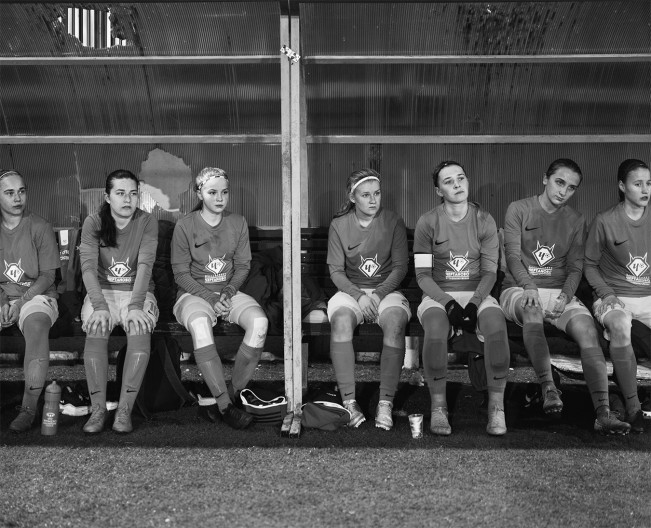

Overtime is a photobook that focuses on a football boarding school and its professional women’s team on the outskirts of Moscow. It witnesses how queer teenagers come of age within systems of discipline, belonging, and visibility.

My interest in the football environment grew out of experiences I share with the players: early involvement in sport—rhythmic gymnastics in my case—and the process of recognizing and negotiating one’s queerness. The photobook attends to the strategies of survival and moments of refuge that emerge through the game itself and through collective participation.

Off camera lies the political context in which the team represents the values of a society that denies queer identities legal recognition, criminalizes public visibility, and forces ongoing self-regulation as a condition of safety.

The photographs were made over four football seasons and trace the everyday life of the community: on the field, in the locker room and at the informal gatherings. The images are a visceral testament to the temporary nature of physical states—fatigue, injury, recovery, moments of strength—that athletes experience with particular intensity. The players are surrounded by a working-class suburb where vegetation pushes through concrete and prefabricated housing blocks, fruit ripens quickly, and summers are brief. These images outline a social landscape of growing up—proletarian and suffocatingly heteronormative. This landscape functions as an active force within the project, permitting the protagonists’ presence only within narrowly defined zones: on the field, in the locker room, inside the team.

Within these boundaries, photography becomes a tool of visual validation and self-presentation. For the players, being photographed is part of shaping a shared visibility and affirming their position as athletes; for me, it is a way of registering a community whose public queer visibility is legally restricted and socially policed in contemporary Russia.

The football world remains a bubble, while changing cultural norms and ideology are gradually squeezing the oxygen out of other spaces. Inside the bubble, rules of close-knit solidarity apply, but outside it, the same bodies and gestures instantly become vulnerable and require camouflage. The viewer observes how female footballers adopt a collective identity: they get tattoos, wear sports brands and, instead of being labelled as pro-Western teenagers or feminists, become visible primarily as athletes.

Overtime speaks of a desire to belong, to love, and to be loved. The book constructs a reality shaped by a specific historical and professional context, in which intimacy, growth, and care unfold within a limited season. The final section of the series links bodily injuries and emotional experience to the recurring motif of apples—introduced as signs of ripening and abundance and culminating in the image of apples discarded on the roadside.

Yana Nosenko: What initial impulse or set of questions led you to begin Overtime?

Margo Ovcharenko: Encountering the team was striking. The place felt emotionally charged; the field had air and light the city didn’t. The players moved as individuals and as one body. What stayed with me was not only the overlap between sport and queer life, but how sharply this community contrasted with its surroundings and with other queer spaces I’d known. That friction between visibility and isolation became the starting point.

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

YN: Given that your interest grew out of shared athletic and queer experience, how did that translate into your first encounters with the team, and how did trust take shape over the four seasons you worked together?

MO: I didn’t arrive with declarations or questions about identity. I don’t like hierarchy in portraiture. I respect people’s choices and limits. Early on, openness felt impossible. Years later, trust shifted as I was perceived as safe and open, and some couples wanted to be photographed. Those images remain partial, shaped as much by caution as desire.

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

YN: What role does seasonality play in the emotional rhythm of the project, and how did the recurring motif of apples emerge and evolve in relation to that sense of ripening and impermanence?

MO: I didn’t choose motifs, seasonality set the pace. I shot 35,000 images over four years, and things kept repeating because they were there. When I was in Shanghai, an editor invited by the publisher, Tintin Wong, noticed the apple photograph that appears as the final image in the book, and together we identified and included the first one. Apples in bloom, then ripening. They became a way to register time passing. I don’t mind the religious connotation, but I don’t find it very fitting. Another possible read is that the apples are about female bodies becoming overripe, but my strong desire was for the sequence to read as a reflection on how short youth is, and how brief football careers are.

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

YN: You’ve previously examined the pressures placed on bodies. In Overtime, how do states of fatigue, injury, and recovery parallel emotional or psychological vulnerability?

MO: Most of the footballers were 15 to 23. At that age, under that pressure, everything that happens to your body matters. Physical and mental stamina decide too much. In the project, this vulnerability is addressed through visceral close-ups; without them, you only get clean sports images and miss where it actually hurts.

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

YN: The series speaks to a desire to belong and to be loved. How does care circulate within the team, and how is it shaped by the structures of sport, discipline, and collective life?

MO: The team was not a unified body. Internalized homophobia, heartbreak, and contradiction were constant. Yet for many of these teens, the football world, with all of its silence, was still more accepting and less isolating than anything outside it.

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

YN: Were there moments you decided not to photograph, and how might those absences, and the book itself, shift if the work were made in a country with different social and political priorities?

MO: This work couldn’t exist like this in a country without state-backed erasure of queer identity. In a context of social and legal acceptance, it would be about something else. Many moments remained unphotographed because visibility carried risk, and because full visibility would also make the work flatter, leaving less for the viewer to arrive at independently. What compelled me was the contradiction: a high-level team that remains poor, unseen, and shaped by constant danger—by being marked as treacherous to the regime, a risk I shared as an artist.

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

YN: You’ve described documentary portraiture as a powerful tool, particularly when applied to athletes whose public image is historically shaped by the state as a stand-in for its power. Has working on the book changed how you think about photography as a political tool?

MO: Working on the book complicated my sense of documentary portraiture. Athletes represent the power of the state and I knew it mattered from day one. Yet, I don’t want my work to be read as strictly political. It is about openness, love, and loneliness, but it exists within the politically impossible context of modern-day Russia.

© Margo Ovcharenko from the series Overtime

Yana Nosenko is a multidisciplinary artist and curator originally from Moscow, Russia. Her work explores themes of immigration, displacement, nomadism, and familial separation — drawing from her own experiences and expressed primarily through lens-based media.

She has exhibited at the International Center of Photography Museum, Gala Art Center, MassArt x SoWa, and Abigail Ogilvy Gallery. In 2023, she was awarded a residency at The Studios at MASS MoCA. That same year, she joined the Griffin Museum of Photography as a Curatorial Associate and Exhibition Designer, where she helped co-curate and organize exhibitions, oversaw daily operations, facilitated artist talks and panels, designed marketing materials, and worked closely with visitors and artis

ts. In 2025, Yana was appointed Director of Education and Programming at the Griffin Museum, where she continues to foster artistic dialogue and learning through exhibitions, public programs, and community engagement.

Before focusing on photography, Yana studied graphic design at the Stroganov Moscow Academy of Design and Applied Arts and worked as a graphic designer at Strelka KB, an urban planning firm in Moscow. In 2017, she completed a major independent project: the design of Mayak, a typeface inspired by Soviet Constructivist fonts of the 1920s–30s, later released by ParaType.

She holds an MFA in Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and a certificate from the International Center of Photography.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Margo Ovcharenko: OvertimeJanuary 27th, 2026

-

Yumi Janairo Roth: EFFIGY 1462January 20th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025