J Houston: Tuck + Roll

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Tuck + Roll by J Houston.

J Houston was born in Kalamazoo, Michigan and graduated from Carnegie Mellon University with a focus in art and gender theory. Most recently, they were an artist-in-residence at Otis College of Art and Design, The Growlery, and Vermont Studio Center, and J has received grants from Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council, and Carnegie Mellon University. Their photo work on Pittsburgh’s queer community has been a finalist for the Duke CDS Essay Prize and Silver Eye Center for Photography’s fellowship program, and their work has been shown at Houston Center for Photography, Turner Contemporary, Aviary Gallery, Amos Eno Gallery, Contact Gallery, Miller Institute of Contemporary Art, Siena Heights University, and New York Photo Festival, among others. This spring, J will have a solo show at The Java Project in Brooklyn.

Tuck + Roll

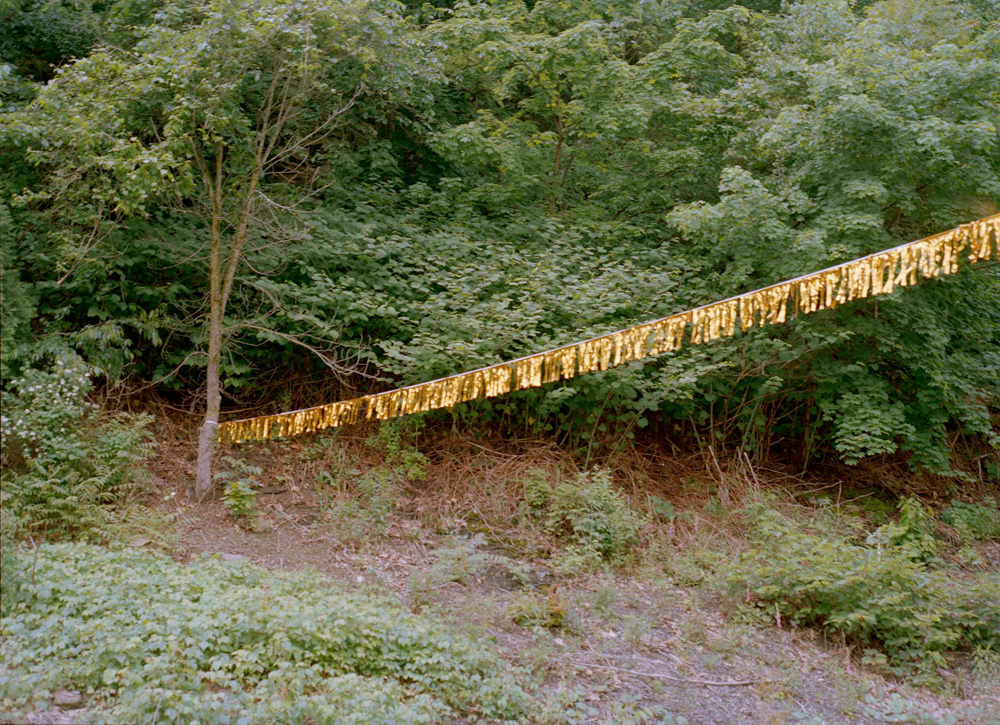

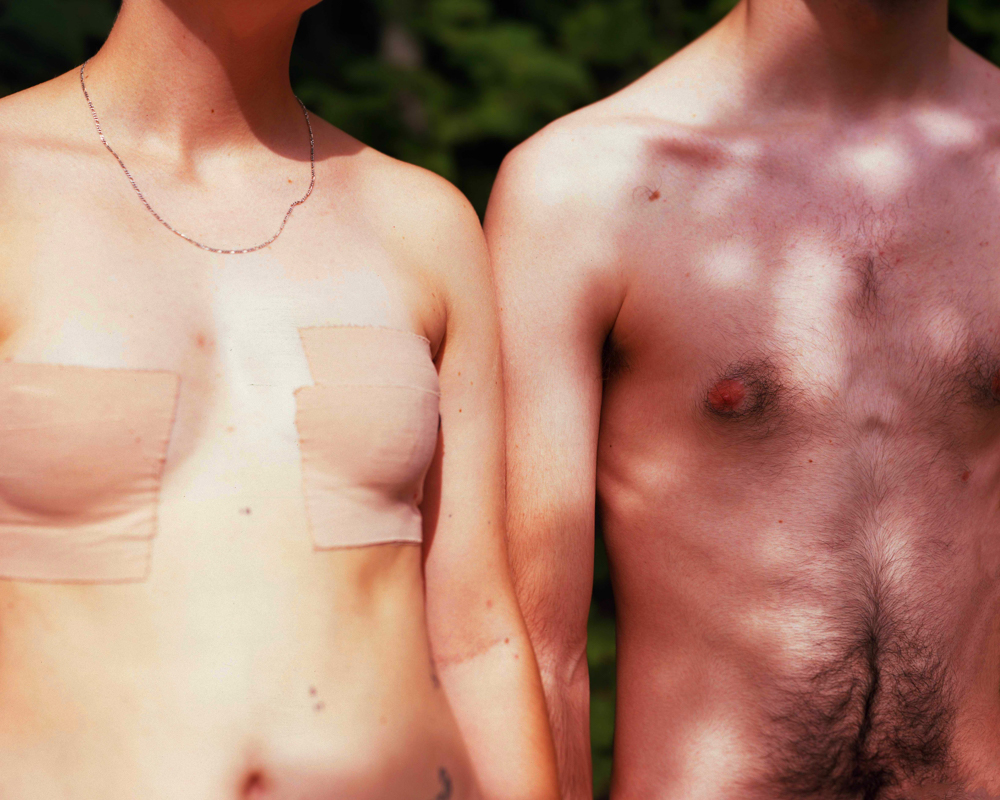

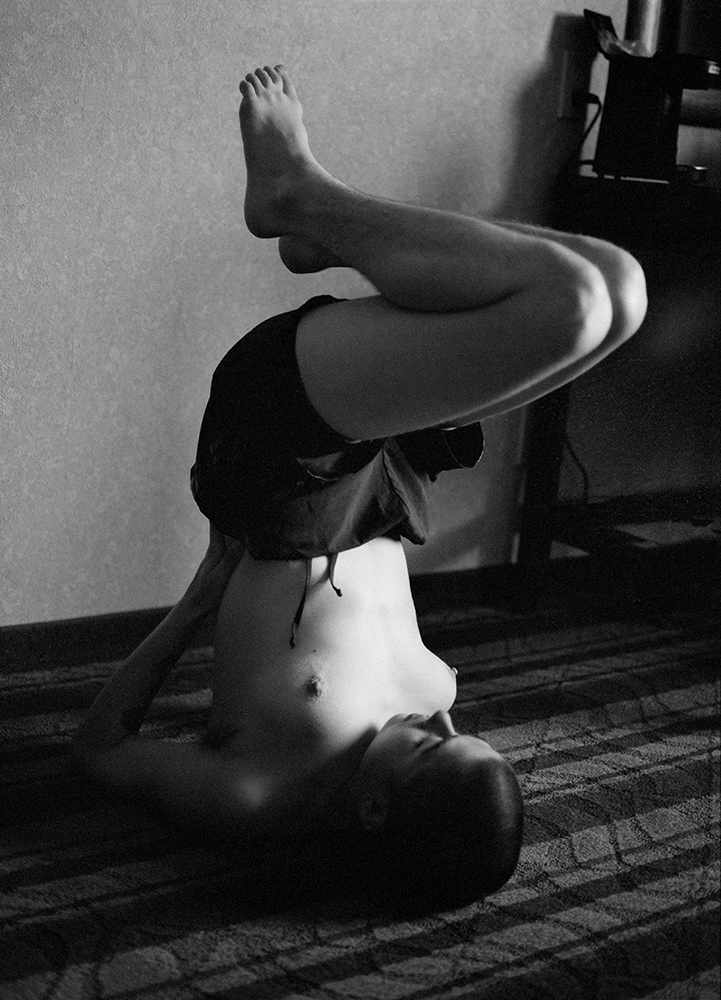

Tuck + Roll* builds a queer community situated in the Midwest, examining what a utopia could look like in domestic and private landscapes through the lens of magical realism. I center collected objects, hair, quiet performance, and unfetishized body, and sitting somewhere between reaction and fantasy, I pull materials integral to queer nightlife into the daylight. Using close friends and trans siblings as stand-ins for biological family, these images manifest a desire to have unconditional relationships without letting go of the landscape I grew up in. The images were made in areas around Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and across Michigan, including friends, family, partners, interiors, and landscapes that repurpose the different layers of erasure experienced in this region. Shot on medium and large-format film, this body of work gives expense and large amounts of time to the queer community, something needed for our representation.

* Tuck + Roll (v.); The technique, almost always done while running, involves diving forward in such a way that your shoulder lands on the ground first, and you roll into a little ball. As you come out of the ball, immediately spring back up into a running stance, or move into a kneeling position.

Daniel George: I am interested in hearing your thoughts on the title of the project.<

J Houston: Tuck + Roll was repurposed out of a definition I found in a manual from Stonewall-era policing. Those words feel very bodily when I think of gender presentation, especially with tucking being a tactic both that transfemme individuals use in the everyday and drag performers use for shows. I also thought of the actual physical movement of being held down and then popping back up, both in conjunction with the twisting and folding of the people in my photographs and mentally within the everyday trans experience.

DG: What prompted your desire to generate this community—even if only visually?<

JH: When I arrived in Pittsburgh at 18, I didn’t know I was trans and wasn’t sure how to begin to enter lgbtqia+ spaces that center gay men and cis folx primarily. Over the next few years, I began to build my own queer family while also learning how to photograph. It felt natural to photograph this chosen family in domestic and private space, as that’s where we convened not feeling comfortable in public or even in parts of our own ‘community’, which is why that word needs more elaborate description sometimes. Over time, I began to look for others who wanted to be seen in this way and through word-of-mouth and social media, we built trust and strangers regularly invited me into their homes. This process also gave me an excuse to become friends with other trans people outside the contexts of dating, creating new relationships that often last even without regular contact.

DG: In your artist statement, you write that you “desire to have unconditional relationships without letting go of the landscape I grew up in.” Do you see an opposition between the two—in their nonideal form? It feels like you are alluding to something more personal—like a connection to place but a detachment from the people.

JH: I do see an opposition between where I lived for the first 10 years of my life in Kalamazoo, MI with biological family and having unconditional love that transcends what gender I am expected to present as or what choices I make. Despite this, I’ve always been excited with the Midwestern gaps between intent and outcome; this could manifest in man-made landscapes or bodily presentation for example. There’s an earnest nature to this slippage that’s hard to describe and just doesn’t happen as often or as interestingly in major coastal cities. It’s very similar to how I experience queerness, as something that often slides back and forth depending on where I have to be, how much time I have, who I’m with, what I feel. I’m often surprised both by my own desires and by moments in Midwestern landscape, which is maybe why I’m fixated on photographing them together. It’s also important to talk about and photograph the different ways queerness exists outside of cities; there are trans and queer people in all kinds rural areas, regardless of how visible they are to those outside them.

DG: Ultimately, what insights of a utopia do you have at this point—after having tasked yourself to set out and create it?

JH: I don’t want to claim any authority over the general idea of utopia, but for me, it would exist if I could present and be perceived in whatever way I dream up that morning. Sometimes when I scan a negative I made of myself and I first see it, for a moment I understand my own body and what I want to be. That same feeling comes occasionally when I scan images of other trans folx or they respond to the images I sent them of themselves. Queer experiences can be so fleeting when they aren’t reaffirmed in the everyday, so really, it just comes down to being seen and having a photo to hold that moment.

DG: In your photographs, you are confronting erasure by divulging characteristics of queer nightlife culture. How do you feel that your images are able to do this effectively? What does the photographic medium foster in terms of visibility?

JH: The stereotyped aspects typically associated with drag and queer nightlife are really beautiful: heavy makeup, sheer fabric, fringe, wigs, jewelry, curtains. I’ve been interested in how pulling them out of that straightforward context and twisting them into the quieter trans work I’m making changes the fetishization that many people experience. Performance can of course be very vulnerable in any context, but how is a performance on a stage surrounded by people different or the same to a performance between just me and the participant? How much does a lens change this? The answers to those questions vary as we aren’t a monolith, but that’s essentially what I’m thinking about when I edit and sequence.

As far as visibility, I didn’t know I could be trans until I saw trans people. People say the internet really opens things up, and maybe it does for some when they are younger, but for me, I didn’t understand my own relationship to gender and desirability outside of the context of performing cis femininity until much later. That’s what drives my desire to make these portraits or self-portraits, thinking of the young people who don’t have trans people in their everyday or live in a place where trans people are only presented in occasional news or spectacle celebrity.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026