Izabela Jurcewicz: Body As a Negative. Sensations of Return.

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Body As a Negative. Sensations of Return by Izabela Jurcewicz.

Izabela Jurcewicz’s photographs have been exhibited in over thirty exhibitions, including such venues as the International Center of Photography, ClampArt, Baxter St CCNY, School of Visual Arts Flatiron Gallery, Affirmation Arts in New York, RISD Museum and MONA Museum of the Newest Art in Poznan. Her works were presented during such international photography festivals as Unseen Amsterdam (Unseen Dummy Awards 2019), Month of Photography in Bratislava (OFF), 12th Fotofestival in Lodz, 8th Biennale of Photography in Poznan. She was an artist-in-residence at the School of Visual Arts and her works were included in publications by the International Center of Photography, University of Arts in Poznan, Arsenal Gallery in Poznan and BlackBox Gallery in Portland. Recent talks given at the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester and Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Izabela is a graduate of International Center of Photography and received an MFA in Photography at the Rhode Island School of Design, where she recently taught as well. Izabela is currently a lecturer at the University of Arts in Poznan at the Photography Department.

Body As a Negative

In my performative and therapeutic process of dealing with memories and tensions written in the body, photography takes a crucial role. I was an interorgan tumor patient, one of 300 cases worldwide, where science had few answers to the cause and how to proceed. This experience of a patient being ‘on view,’ researched and scanned, coined my relationship with the camera and ways of seeing a human body.

Medical experiences, especially surgeries, live as a photographic negative in my life, which hence- forth produce images. Deep somatic memory is called to visibility in my work, externalised through the photographic surface.

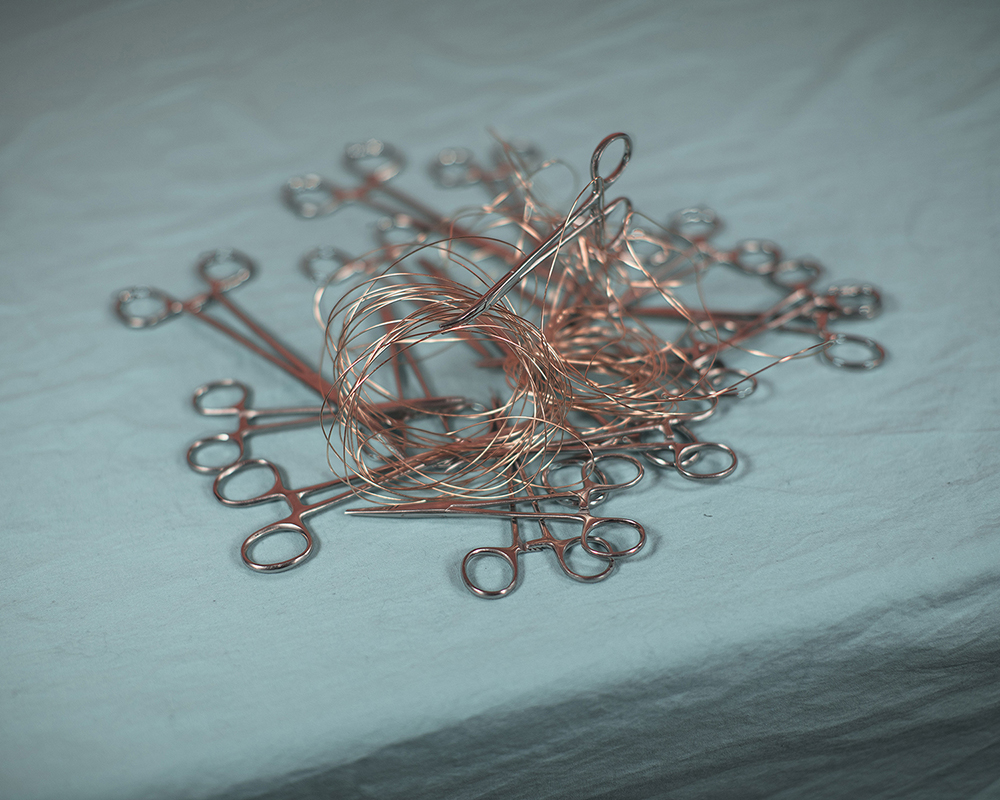

In “Body as a Negative. Sensations of Return” I replace the invasive surgical instrument with my camera as a receptive device to register, merge and enable a ritual of healing. To synchronize the level of knowledge in my body and mind, I began re-performing the trauma under my conditions and re-writing my memories. The practice of requesting the body and self to be ‘in tune’ opens a dual process: a spiraling inward toward the past and a reclamation of my inherent life force.

It is this process of emphatic engagement that brings dimensionality to the body and self again, and grows a capacity to join with the suffering of others. From my work I than see my Father, sup- porting him through his own cycle of trauma, as he had cancer from 2016 to 2019.

“Body as a Negative. Sensations of Return” consists of a self-published photobook including 33 photographs with text (shortlisted at Unseen Dummy Awards 2019), as well as installation work that shows a relation between unique glass pieces (merged with negatives) with medical lights and photographs. The project is planned to be showed at Les Rencontres d’Arles 2020 as a part of 2020 Dior Photography & Visual Arts Award for Young Talents.

Daniel George: You mention that with your rare diagnosis, there weren’t many places to look for answers. I imagine that your head was spinning for a period of time. I am curious at what point you began thinking about your experience as “a patient being on view” as something worth exploring visually. When did those ideas present themselves in your mind?

Izabela Jurcewicz: While being scanned by ultrasound or tomography at the hospital I was intrigued. That was the moment when I started thinking about the link, similarities and differences, between medical equipment and my own camera while looking at the human body. Right after I came back home from the hospital after the first surgery, I took photos of my changed body, as I wanted to see myself and also have this document of myself. I did take photos of the body periodically, when I felt that there was something off with it. The need to see myself from an outside perspective, to examine myself was a result of this experience of being a patient “on view”.

But it wasn’t really until my Dad was diagnosed with a fourth stage cancer in 2016, that I felt like my body was again set on alarm and I had to look into it, into the body and to understand what was actually happening. That’s when I felt an urge to fully visually explore this idea. As I had deep empathy for my father’s experiences, I started feeling psychosomatic tensions in my own body. From one of my therapists I learned that sources of pain and anxiety are held in unseen layers of the unconscious and subconscious mind. Those memories can be located throughout the body in all kinds of cells, not only in the brain. Neuroscience research refers to these traumatic, autobiographical memories as cellular memories. Whenever I am in a stressful situation, these traumatic memories open up in the cells as if I were again fighting for my life on the surgical table. I have developed a hypersensitive internal alarm system, which activates even in harmless situations. Serious about understanding my body, I turned a lens of attention on it. I returned to my photographic practice as a reliable companion, drawing upon my familiar intimacy with the lens yet now turning it solely upon myself. To synchronize the level of knowledge in my body and mind, I began re-performing the trauma under my conditions and re-writing my memories. I felt like both therapist and patient. As an extension of the healing treatments, my photographic process allowed me to settle into my body.

DG: Why was it important for you to personally revisit the physical anguish of this experience through photography? And throughout this performance, where you also wrote your memories, what do you feel was made manifest?

IJ: I intuitively felt like the camera was the right medium to deal with memories. I spent weeks in hospital, stabilized after the bleeding and awaiting my first surgery. The first procedure lasted nine hours. Being cut and left open for so long changed my body at a cellular level, leaving signs of stress and anxiety connected to the threat of survival. The impact of this surgery exists as a living archive in my body, a photographic negative that produces images, including the ones that formed the book Body as a Negative. Sensations of Return. I was re-writing the traumatic memories on my own conditions in front of the camera, hoping to change them not only in my awareness but also on the cellular level of the body, so they wouldn’t come back in another moment of anxiety in my life. Through returning to the memories and reperforming them under my conditions, my body gained peace and vitality. When memories were transformed on a cellular level, the body became balanced as if anew. This body as a negative was not static; rather it was a repository of emotion and of ease and freedom. That’s how Body as a Negative. Sensations of Return began.

The practice of requesting the body and self to be ‘in tune’ opened a dual process: a spiraling inward toward the past and a reclamation of my inherent life force. Two words describe time: chronos (the chronological or sequential time) and kairos(proper, opportune time for action). While chronos is quantitative, kairos is qualitative. Whenever I photograph myself, I enter the non-linear sense of time — kairos. Kairos is believed to be a soul / self-nourishing time. In kairos there is only the present moment. To achieve it, we must let go of everything else. Though I find the time of making self-portraits related to my soul, my feelings, the ephemeral internal life, there is a strong bodily and surface-related reaction to it. Deep somatic memory is called to visibility in this work, externalized through the photographic surface. In this act of return, I replaced the invasive surgical instrument with my camera as a receptive device to register, merge and enable a ritual of healing.

DG: Your descriptions of these photographs are equally as arresting as the images themselves, as they allow me to become further engrossed in your experience. Why did you feel it was crucial that this project have a written component?

IJ: I thought that in order to fully transmit the depth of the work I needed to include the writing component in the photobook. In this work I deal with issues that are not highly well-known like cellular body memory, and I wanted to share those concepts with the viewer.

At the same time writing about my memories was another way to re-live the trauma. It worked as an addition into taking photographs to achieve some kind of katharsis from the trauma.

The idea to divide the work into different written chapters was important to signify the different states of the body and my awareness of it. The book starts with Stilled – I was already feeling the fear of the situation and was awaiting the treatment, but I was too scared to emotionally process what was happening. I didn’t want to fall apart. Somnolent, yet breathing goes back to moments of vulnerability in the process of medical procedures performed on the body. Tremblerefers to re-living the trauma, either subconsciously, expecting a consecutive surgery or after hearing a diagnosis of my father’s cancer. Those tensions written in the body and anxiety lead into my attempts to have the body and self ‘in tune’ – which is showed in Attuned. Finally, after experiences of re-writing the memories and using treatments (like tuning forks or micro-kinesitherapy) to put the body into balance and processing the story emotionally results in the feeling of my return into the body and taking control of it. Therefore, it ends with Return, a short description of what this work meant for me and why photography was crucial to achieve it.

DG: I am interested in the incorporation of elements from the natural world in your photographs. Could you speak more on your intentions in using those things?

IJ: Vessels. Fish. Shells. Butterflies. Specimens. Glass. They all become stand-ins to express the emotional states and visions imprinted upon me. I wanted to achieve some kind of release, and actually recognize the shapes that these visions take in the real world. For example, I was making a photograph of crop and vessel thinking about the pain and body experience I underwent in regards to surgeries (photograph Inside). Using the elements from natural world was very intuitive, but I think it comes from fragility of those elements, as well as the fragility of human body.

DG: With this work, you are using photography to “enable the ritual of healing.” What insights do you have now, regarding the therapeutic value of art making?

IJ: The act of mirroring was central to my recovery. I re-created the traumatic memories as a patient in the safe, private (or semi-private) space of the studio. It was crucial to remove myself from an actual medical space in order to re-live those experiences in a therapeutic way. In setting the studio stage, I assembled a hospital room and the surgical apparati. On other occasions, I photographed myself triggered by hospital-referenced objects, which became indexes for the memories, pointing back to experiences from the Western medical treatment. The camera became a witness to moments of replaying difficult experiences, on my own terms and under my conditions. Using the camera allowed me to see my body integrated (in opposition to cut and open during the surgeries) giving grounds to feel safe. Each print functions as my mirror, merging my sense of body and self. I would replay each memory until I felt some kind of release and could move on to the next one. With each image taking control of it, making a composition and putting the settings on, and almost at the same time being in front of the camera – gave me this feeling of being both a therapist and a patient.

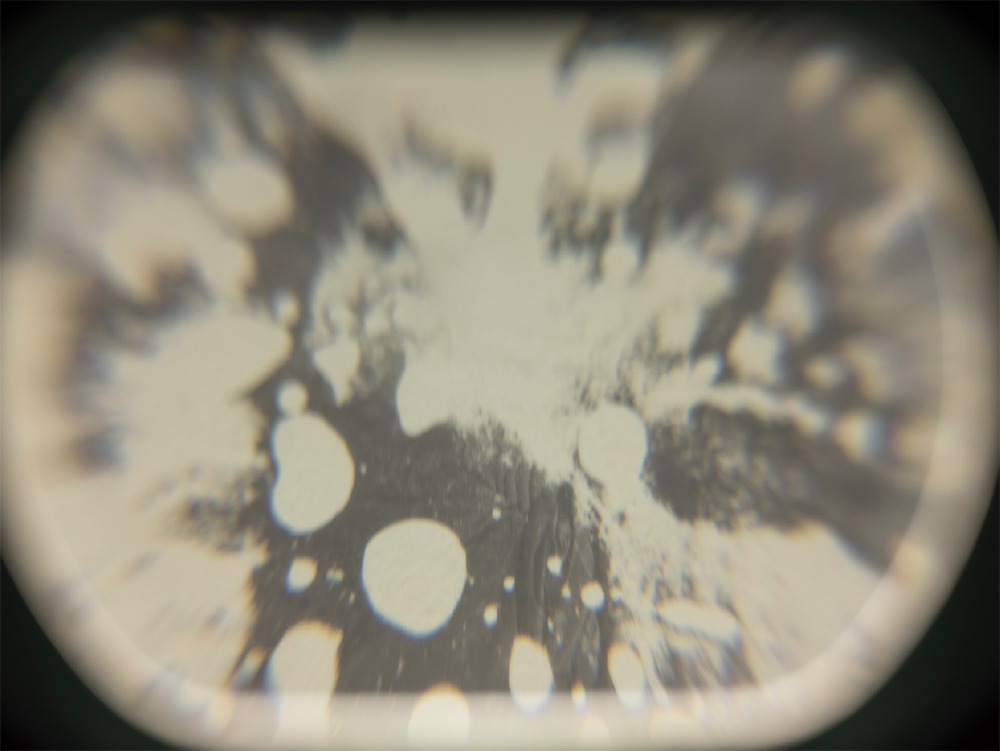

While working on “Body as a Negative. Sensations of Return” I became mesmerized by glass and its transformative capacities. Forming the memories in glass additionally to my therapeutic photographic practice felt urgent. I started making replicas of my abdominal area, where my skin became glass and no organs inside. Nothing. Making glass casting molds was another ritual. It was a very physical process. My skin and scar surface were impressed into a negative, translated into a wax positive and finally into a plaster/silica heavy mold that served as a negative for a glass positive. It was a protracted process, involving external help to get the first body negative from my skin, and to carry on the final mold to a kiln.

The fire slumped the glass onto the mold, and in a temperature that would cause ultimate death and scattering of the body into dust — my DNA and scars are impressed on a glass plate, formed during this process into a body shape. I was adding negatives onto glass, experimenting with the idea of body as a negative. It felt very transformative.

I focused on both photography and casting, as they both function as a proof of the thing that has been. Photography exists as an indexical twin to casting – as an imprint of oneself, of memory and of history. Both in photographing and by re-photographing my scarred abdominal area and in casting this body part and merging with my negatives, I explored my vulnerability.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Martin Stranka: All My StrangersDecember 14th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025

-

MG Vander Elst: SilencesOctober 21st, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Josh BirnbaumOctober 10th, 2025

-

Aiko Wakao Austin: What we inheritOctober 9th, 2025