South Korea Week: Han Sungpil: Fusing Future

“The Sea I Dreamt…..

Burying all my pain, hatred and sorrow,

Sinking my yearning and regret,

Sailing my hope and dream,

I glance at the sea.

The sea, for me, carries memories of my personal

experience and history.

At the age of fifteen, I, for the first time, saw the sea, ……”

Portion of a poem written by photographer, Han Sungpil

My interview with Photographer Han Sungpil was held at a special location called, “Zoom.” Due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, online meetings over the Zoom platform have become commonplace and given this accessibility, I was able to grab a hold of Han remotely while he was busy shooting his current work in Canada. The works of Han are unexpectedly timely given the COVID-19 situation. His series have brought important awareness to the changing tides of our modern-day civilization as the global community goes through major changes due to the pandemic.

Every time I interview photographers, I always feel a great deal of respect, curiosity and awe for their work. But Han particularly stood out to me and has been hands-down, one of the most inspiring photographers I’ve met so far.

Similar to the historical figures such as Amundsen of Norway and Robert Scott of England, Han has explored the extreme regions of the world. In doing so, his work through art photography captures both the destruction of nature and the human-induced societal and cultural changes often resulting in unintended consequences to our environment.

Han’s first work is titled “My Sea” from 1988. This is when he first discovered his interests and curiosity to explore nature. The photos from “My Sea” showcase the historical events and environmental issues derived from nature through his own artistic perspective. The value and meaning born out of this work is one of a kind, and this is the result of his work process which consists of persistent research and experimental spirit.

At the age of 15, his encounter with the mystique of the sea combined with his personal memories and experiences took him to the very edge of the Earth — the polar regions. Ever since then, he has been travelling all over the world for the past 20 years.

Starting in Europe, he’s gone from London, Paris, Berlin, Munich, Madrid, Rome, and Istanbul to the jungles of Cuba, Australia, Indonesia, the Gobi Desert, and the polar regions of Mongolia. Han Sungpil endeavors an endless pursuit of grand journeys dedicated to his devotion to photography.

However, his longingness to travel doesn’t simply emerge from his curiosity to explore physical spaces. It stems deeply from his enduring passion, discipline and will of a lifelong practitioner in the space of art photography.

Further, his physical space explorations contain thematic elements of time & memory, real vs. fake, and reality vs. the imaginary. On top of these provocations, he introduces discourse around relationships such as Earth and nature, nature and human civilization, as well as serious environmental issues born out of human greed and desire.

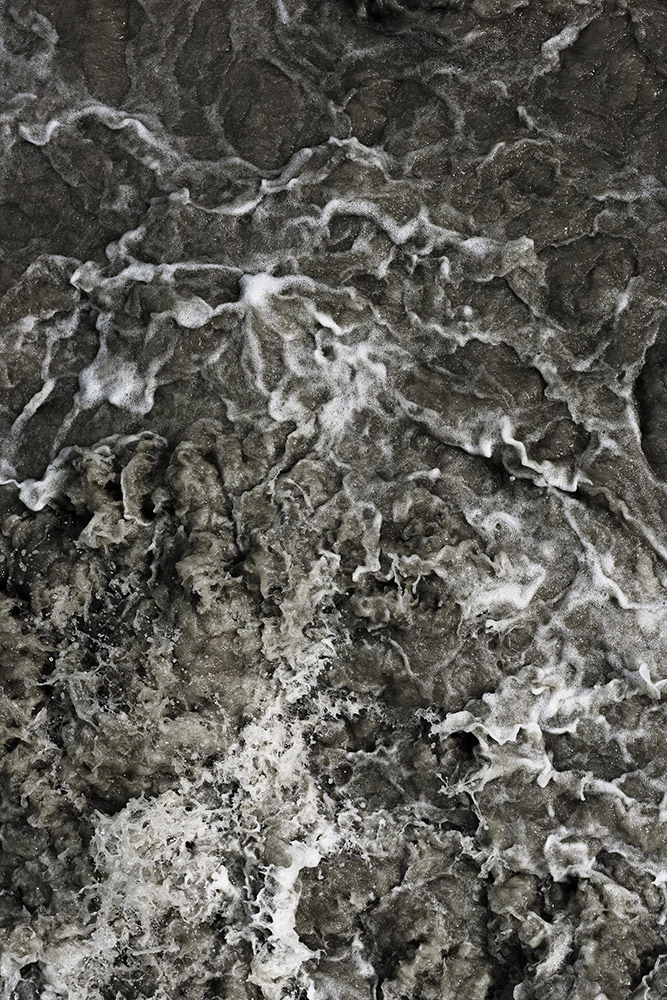

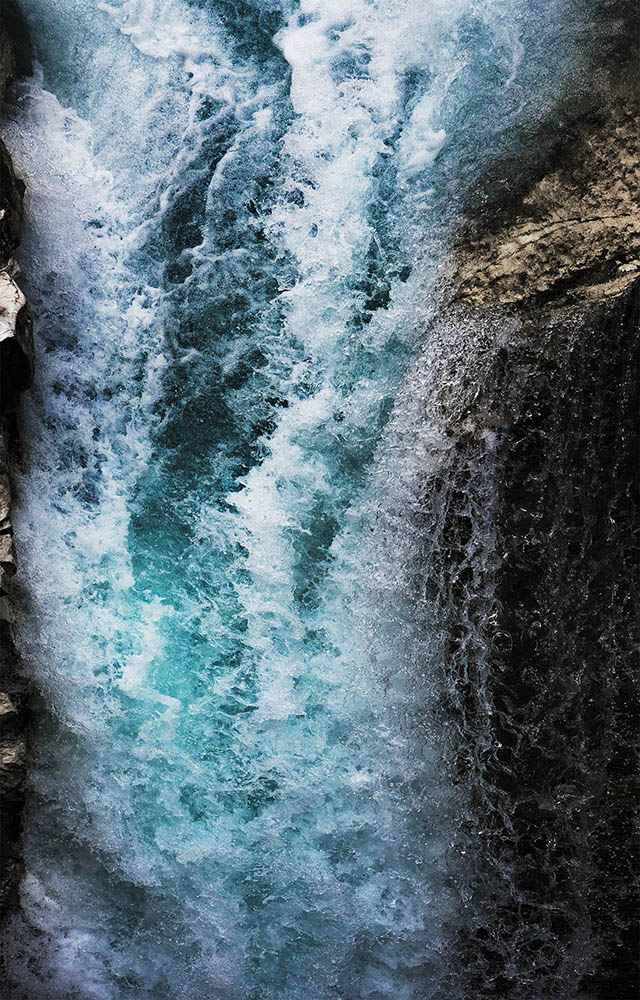

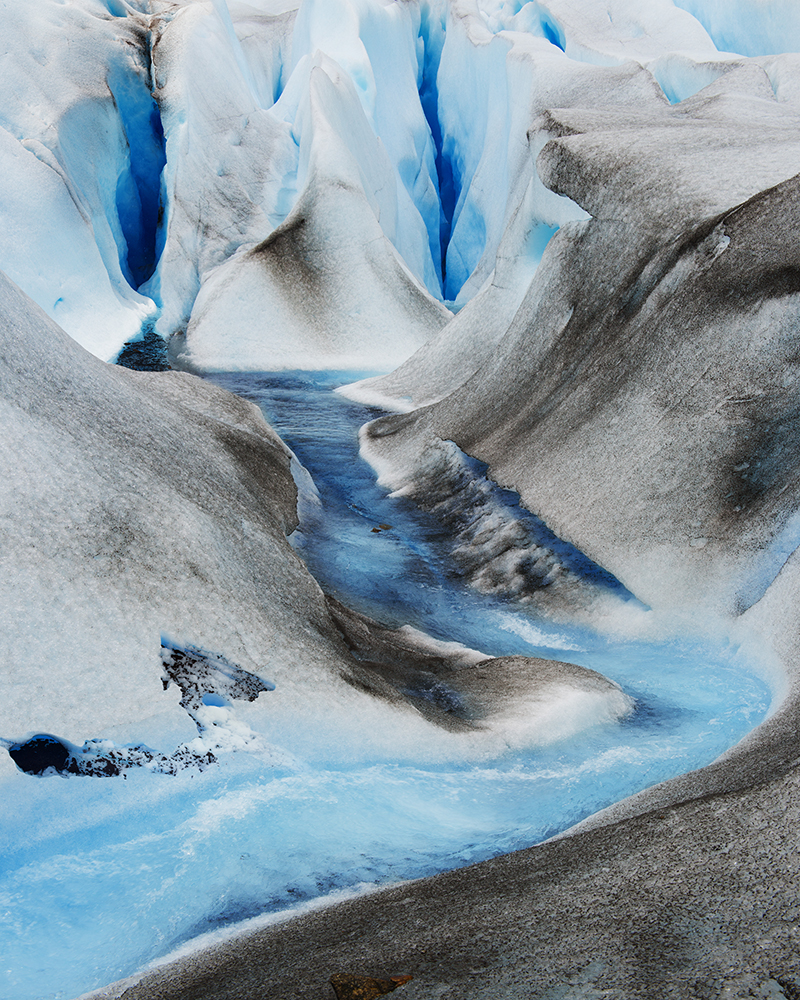

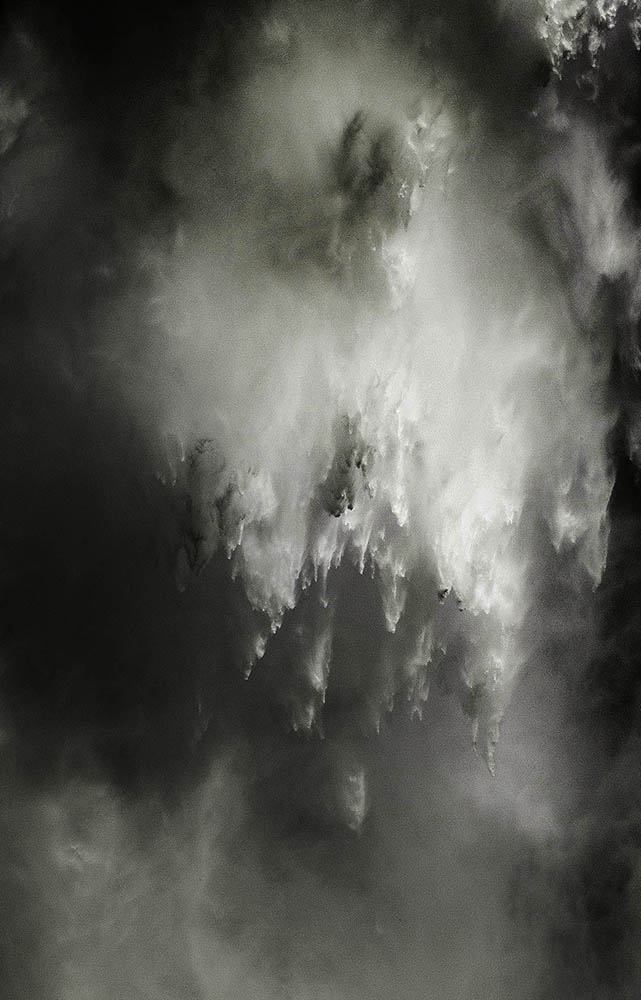

Although humanity today is faced with extremely dire environmental problems, the global community struggles to make meaningful efforts to create change and become more Earth-conscious. At an initial glance, Han’s series titled, “Fusing Future” (which captured the landscapes of the North and South Poles) is reminiscent of the painting “The Sea of Ice,” by Caspar David Friedrich, A German painter during the romanticism era of the early 19th century.

At the visual surface of Han’s “Fusing Future,” viewers immediately feel a sense of nature’s sublimeness. This is a Kantian type of sublime, which sits at the realm of human’s ability to grasp one’s own emotional awareness. This transcendental feeling of being overwhelmed and consumed by the vastness of nature is a universal experience that every human goes through. However, underneath the first visual layer, there is much more to the imagery than just sublimeness.

Historically, the geographic location of the Antarctic and North Pole were exploited by human industrial needs, particularly known to be places where whale oil was used as fuel before petroleum oil. Nature, which usually provides humans with unique subliminal feelings and enormous transcendental power, has been manipulated as an object of human industrial exploitation and for human pleasures like tourism.

Thus, the consistent theme built into “Fusing Future” is not about fulfilling an aesthetic taste extracted from landscape photography. Rather, Hans strives to provide symbolic representation of the problems arising from human desires and interests.

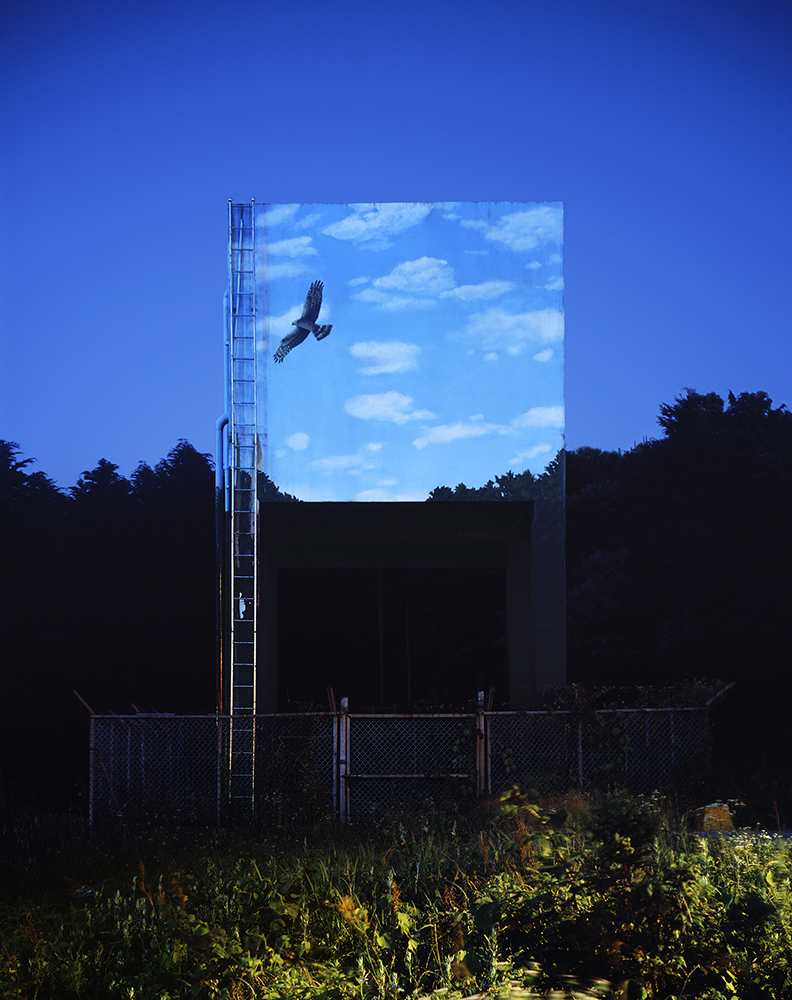

Alongside his works on nature landscapes, Han’s “Façade,” is another highly-acclaimed series that tackles the concepts of reality and fiction as he uses photography to reproduce the line between realistic and fictional boundaries — where oftentimes, those boundaries are murky and confusing.

Out of the countless notable works that Han has created, I have chosen to focus on “Fusing Future” and “Façade” for this Lenscratch article. I hope you’ll find the same level of inspiration I did for his work and process, and please feel free to explore more of his series on his personal website.

Façade

Since I saw the spectacle of the St Paul’s Cathedral in London, I have been confounded by the scene. It was covered by scaffolding with a life-size painting, an exact replica, of the cathedral. The separation between reality and simulation collapsed before my naked eyes. Depending on where I stood, as my perspective shifted, the building was travelling between the realm of realism and that of hyper-reality. For me, it was surreal. The life-size painting of the cathedral masked the original, but also stood in for it. The reality of the sight welcomed many passers-by and visitors.

There are two streams of thought in art history. One seeks to imitate the real world and the other to project the ideal. These two streams have always been at odds with each other; the history of art has been a dialogue between realism and idealism.

When the science was advanced enabling to represent a perspective during the Renaissance, it offered a way to capture the three-dimensional reality into a two dimensional plane. The invention of photography in 1839 was sensational as images became so real as to appear life-like. The photography medium made possible to convert a three-dimensional object into the fixed two-dimension.

However, when a photograph represents a two-dimensional perspective painting, does this represent a three-dimensional reality or offer its mirror image?

My question in ‘Facade’ is: what does such a photography imply? The real or the ideal? The body of work that I produced after carefully observing the St Paul’s Cathedral examines photography’s ambivalent role in representation.

From the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, there was a controversy between style imitating the salon-like pictorial atmosphere and that of pictorial photography.

In the post-war era, the hyper-realism and photo realism emerged. In the digital era, the boundary between painting and photography was blurred, which resulted in hybridising forms. These two genres became indistinguishable.

If the photographic technique produces a visual image to the exact size and shape of the object it represents, would it be a photograph or a painting?

What happens if an artist manipulated digitalised photographic image by using computer techniques to enhance it much better than the previous representation?

In addition, if an artist literally photographed a photo-realist painting, is the resulting image a photograph or a painting?

‘Facade’ explores the fluidity between the real and the ideal. My photographs portray the trompe l’oeil paintings decorated on the scaffolding, the covering, and the wall. In my opinion, they are simply there to fulfill the human desire to experience the ideal in this real world. It is the desire instable in the urban spaces in our contemporary era.

Your path to becoming a photographer is impressive. You first graduated with a major in German, but further pursued another degree in photography at Chung-Ang University. That meant you had to study for the college entrance exams again. I can see that you’ve carried out this persistence and passion throughout the past 20 years, as an acclaimed photographer. I’d love to know where you discovered this driving force.

My parents were actually not pleased with my decisions to pursue photography, but I followed my gut. After taking the college exams again and getting accepted into the photography program, I knew in my heart that this was my path. Having found this calling within myself, I was driven to study hard at school. I graduated at the top of my class and was able to earn a graduate degree at Kingston University in London. The opportunity to study abroad expanded my learning horizons, and I continued to work very diligently in graduate school. I think my educational years have a lot to do with my success and my dreams of becoming a photographer.

I was a very curious child growing up. I was fascinated by the idea of a world filled with unknowns and mysteries. I attribute these childhood traits of mine as one of the driving forces of my persistence to carry out my passion in photography. When I find interest in something, I get hooked. And I do everything I can to explore and figure out what I don’t know. Second, I believe that artists in particular, should be in constant pursuit of communicating with others and understanding one another. It’s what we can, as individuals, do collectively to make humanity better. This belief system is another trait that’s made me the photographer I am today.

What motivated you to incorporate the Antarctic and Arctic glaciers in your work?

I have been interested in the Antarctic and the North Pole since I was a child. It was my dream to visit that area. A glacier is a place where snow has built up over tens of thousands of years ago. To me, the South and North Pole are regarded as subjects of subliminal accumulation, and the consistently layered material accumulation of the sublime, and the enormous amount of the time embedded in that accumulation is transcendental. I wanted to capture that accumulation of time in my work.

Fusing Future is about the intensive melting of the glaciers in the Canadian Rockies. Iceland, Patagonia, the Andes, the Arctic Circle and Antarctica.

Mountain glaciers, given their sensitivity to warming, are showing the earliest and most dramatic signs of ice loss. The effects of global warming, while not immediate, are potentially catastrophic all over the world. The sea level and global stability depend on how these great masses of recrystallized snow evolve. On average, most of Earth’s Mountain glaciers are continuing to melt. Scientists know this by calculating the glaciers’ “average mass balance”: taking accumulated snowfall on those glaciers and subtracting ice losses due to melting, meltwater runoff (drainage away from glaciers) and evaporation (when a liquid turns into a gas). Their calculations show decades of more ice losses than gains. For example, the Canadian Rockies’s glaciers will be almost entirely devoid of glaciers by the end of the century. While the coat of dark specks provides its visitors with an aesthetically astonishing view, little is lovely about the science behind the scenes. As the dingy flecks the uncountable number of black particles which called ‘cryoconite dusts’ absorb solar heat more efficiently than the snow and ice, they quickly melt the snow and ice underneath and drill holes, named “Cryoconite holes”, can develop into lakes, severe rupture in the various glacial areas. A combination of the massive volume of water in the lakes and the burst of ice causes GLOFs (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods), and its many victims.

I’m aware that it’s very difficult to photograph the Antarctic and the North Pole. It also must have required a lot of money and manpower. How did you make all of this possible?

First of all, I generally put a lot of initial effort into researching the place and subject I intend to photograph. I gather a great deal of information about the place, it’s history and culture, the stories of people living there, etc. As I do most of my research through SNS (social media), I use those platforms to apply for funds and gather donations. Various countries also provide financial support, which is another avenue to cover budgets. In some cases, artists from different countries come together and work on projects together.

What was your experience when you went to the polar region, a place you had desired to visit when you were young?

The actual appearance of the polar region was different from what I knew it to be. I eventually discovered that an environmental change had occurred. Glaciers are rapidly collapsing and melting due to the ‘Cryoconite Hole’, a hole formed by the accumulation of pollution and dust on the earth. Specifically, glaciers were rapidly collapsing and melting, due to the ‘Cryoconite Hole’, which is formed by the impact of pollution and dust. As a result, lakes and rivers were created at rapid speed.

I was shocked when I flew from Norway to the Arctic and changed boats to Svalbard in the Arctic Circle in 2013. There was a huge amount of garbage that appeared due to the current. But garbage wasn’t the only problem. The accumulation and geographic evolution of the Arctic region that had occurred over thousands of years was quickly being dismantled. Given these apparent changes and the misery that followed, I captured what I saw and shared it to the world.

Along with your work in the polar regions, you also have series that contain themes about human history, nature and human civilization from various angles. What motivated you to be particularly interested in the dynamic between humans and nature?

My childhood yearning for the unknown was similar to that of explorers. Starting from my longing and curiosity for the unknown, I’ve been deeply interested in human beings, the history of humans, and issues derived from historical facts. When we look at the history of energy usage around the world, the United States and Europe used whale oil for streetlamps. On top of those examples, places like the Norway mines and France’s nuclear power plants have contributed to the changes in human society and environmental problems we face today.

Just like in Herman Melville’s 1851 novel, “Moby-Dick” or “The Whale,” I came to realize that the Earth we’re currently living in faces severe environmental issues born out of the vicious cycles of materialistic consumption and profits of capitalism. Thus, I decided to use my exploration of physical spaces in my photographic work to shed light on environmental problems. For instance, there was a time when I believed that jungles were utopia. I decided to go check it out for myself by visiting the jungles in Indonesia. That’s when I witnessed the people there burning down the beautiful jungles to create farms for the surge in demand for palm oil. What I saw was a grim scene of natural destruction and severe environmental pollution — none of which could ever be restored again. My work is not to denounce those scenes and actions. Rather, I want my viewers to think more critically about the destruction of nature and have a mental dialogue about what human life means, through my visual lens.

What do you think an artist is?

I believe an artist is one that charts new paths that no one has gone down before. While a craftsman is a technician who specializes in recreating the same artifact or object of production over time, an artist is someone who creates and finds success in their work by placing significant investment — time and effort — into figuring out the right metaphors and unique conceptualization of their given work.

Critics:

“Han Sungpil is obsessed with reflecting upon time: on what has past and what will come. He focuses on distant and familiar places. On his artistic excursions he takes us to polar ice caps—where most of humanity will never visit—and to the backyards of one of Europe’s most prominent energy resources. By viewing the photographs, we are instantly interacting with an invitation to enter the stages of past histories and future concerns. We are lured by the image’s composition, the atmospheres, and the haptic beauty of landscapes.

To question his own beliefs and stereotypes, Han Sungpil visited the grandeur of the Artic and Antarctica, as well as the controversial home fields of France’s nuclear energy.

The terrains found in both the polar worlds and along the Loire and Seine rivers are home to man-made industry, epitomizing phenomena of the Anthropocene Age. We are in a period where our own dependency and technological achievements are drastically altering the face and atmosphere of our planet. What is present in the series Polar Air and Ground Cloud is that these landscapes are locations where energy resources are won by man. Beyond the visual splendor in many of these photographs, prosperity and community, death and hardship, global economics and society’s fear of the worst-case scenario linger in these images.

Han Sungpil is known for his fascination with irony in the sublime vistas he chooses to photograph. In Ground Cloud 2005 & 2015, we view stunning landscapes with mesmerizing, surreal cloud formations, which stem from a nuclear cooling tower. The movement of atmospheric conditions has been a fascination for the photographer since the beginning of his career.

He first saw the sea when he was fifteen years old. Staring into the water was the catalyst for his first internationally recognized photographic series, the The Sea I Dreamt, 1999-2002. As in the seascapes, the movement of air and water become something otherworldly in Ground Cloud. The vapors allude to movement and thus to time passing. The transforming luminosity of dusk and dawn serve the photographer well when shooting, particularly in these dramatic countrysides. Through long exposures, the skies give way to hues which are revealed in the photograph, but which the human eye is incapable of experiencing.

In the mid-nineteenth century, landscape photography was carried out primarily under the auspice of exploration and conquest. Through these pictures, a broader public could see ancient ruins, and also the magnificence of places they had read about, documented in a way which was extraordinarily real. The new medium helped choose and determine borders, as well as investigate the geological wealth of a terrain. In 1861, the French photographer Auguste-Rosalie Bisson, accompanied by a guide and twenty-five porters for the photographic equipment, made three exposures of the highest Alpine peak of Mont Blanc.1 With today’s technology, Han Sungpil does not need the porters, but some things in the profession remain: the frigid temperatures and storms even with all modernity are not easy to overcome—something that we, as viewers of the photographs, do not experience.

Han Sungpil has chosen to work in desolate topographies with extreme climates. As an artist working under these conditions, the psychological impact is stirred by the physical boundaries one must confront and the isolation in the landscape. Known primarily for his epic project Desert Cantos, Richard Misrach once commented in an interview about his fascination with the desert landscape: “It’s the heat, the feel of the earth, the rich solitude and silence, and the remarkable scale of everything that makes being there so deeply fulfilling. I’ve always had this strange sensation of being a small figure in a vast landscape—as if I were seeing myself from the air.”2

The feeling of isolation creates a particular sensitivity. We are coaxed by Han’s surreal perspectives and the extraordinary scenery. In one image, from Deception Island near the South Pole, a desolate landscape absorbs the corner of a house, and an oversized bone lays in the foreground. It seems here that the photographer has positioned himself to compose a quote to dreams and existentialism encountered in the work of the mid-twentieth-century Surrealists. From two journeys in late autumn and early winter months to the Svalbard Archipelago in the Arctic, Han has brought us deserted interiors of a once thriving community: some rooms consumed by ice. The village panoramas appear as ghost towns with minimal human life: an ominous light sparks from a building, and a faint fume from a factory chimney tarries.

The development of time in the polar regions is described by the artist as three colors: white, red, and black. For him, white means the white caps over 400 years ago, before man discovered that these extreme environs were the habitat for whale communities. Red denotes the blood time in the both the Arctic and Antarctica, when for centuries a global business of hunting and killing whales for their fat and oil provided man with an energy source for lighting. Black symbolizes the period which started when fossil fuels were discovered: coal in the Arctic in the early twentieth century and still today as man drills for crude oil on and near both continents.3

On the shores of the South Shetland Islands and South Georgia, exploitation and extinction of life are layered in remnants of whale bones from the slaughtering. The desolate scenario of the mining towns of the Arctic Svalbard Archipelago is mysterious as it waits for reenactment. The magnitude of seeing a glacier remains breathless. The sublime qualities in Han’s photographs enable a curiosity and an awareness of the extent to which past industrial life has reshaped these environments. It is a reminder of what has been forgotten, and it is a story worth telling. Through a critical form of pictorialism, Han Sungpil’s artwork sings like a siren the evolving dialogue of man and nature.”

From Beyond the Splendor by Celina Lunsford

Han Sungpil (b. 1972, Seoul, Korea)

Han Sungpil practices art mainly by means of photography, video, and installations, covering subjects such as environmental issues, originalities, history, and the relation between the real and the represented.

He strives to understand the world’s diversity by exploring nature and interpreting mundane worlds that have been sources of his inspiration. This process of philosophical inquiry and artistic representation often includes a sense of humor in a subtle manner, incorporating sublime elements of beauty, the objects and concepts we consider worthy to discuss and enjoy at a seminar or festival of aesthetics. Once his works enter the exhibition hall, they become invitations for the appreciators to explore arrays of philosophical questions, one of the most crucial ones being how we can design an ideal synthesis for the post-contemporary.

His works have been exhibited and reviewed at notable venues and events around the world, including the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Seoul and Gwacheon, Korea), National Assembly Library (Seoul, Korea), The Museum of Photography (Seoul, Korea), Museum of Fine Arts (Houston, USA), Chateau de Chaumont (Loire, France), Abbaye Royale de Saint-Riquier (Somme, France), National Museum of Fine Arts (Buenos Aires, Argentina), Museum of Contemporary Art (Shanghai, China), Fotografie Forum Frankfurt (Germany), Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography (Japan), Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts (Japan), Yokohama Triennale (Japan), and Havana Biennial (Cuba).

He received a BFA in photography from Chung-Ang University in Seoul and completed Curating Contemporary Design, a joint MA program offered by Kingston University and the Design Museum, both in London. At this moment, the nomadic artist is working somewhere on Earth, discovering or rediscovering the unknown or the misunderstood.

Sunjoo Lee is a mixed media photographer based in Seoul, South Korea.

Lee’s extraordinary artistic sensibility that was once portrayed through her voice is now visible through the works portrayed through her camera lens. Her photography focuses on a unique lyrical journey into her personal life. She explores her past, present, and future world in a temporal and spatial perspective.

She received a BA in Music from Ewha Women University, a second a second BA in Photography from Chung-Ang University (Academic credit bank system), and an MFA in Plastic Art & Photography from Chung-Ang University Graduate School of Photography in Seoul, Korea. In 2019, she was awarded into the 11th cohort for the prestigious artist residency program at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary Art. Through this residency, she’s currently working on her upcoming series.

Lee’s acclaimed works have been exhibited widely throughout the years in South Korea. Most recently, she had her solo exhibition at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary art, Gwangju Korea. She’s also showcased at Gallery Now, Gallery Gong, Gallery Guha, and more in Seoul, South Korea. Her works are permanently displayed at the Haslla Arts Museum (Gangneung, Korea), and YoungWol Y. Park (Youngwol, Korea).

Her work at large, incorporates everyday objects and subjects to make visual sense of the complexities of human emotions and feelings derived from the intangible, such as music. Her photographic inspiration stems from her experiences of living and travelling abroad. She extracts the memories and various emotions born out of the human connections she’s made during that time of being in foreign spaces.

Building on this conceptual narrative, her work has landed her multiple recognitions, from the 2019 Critical Mass as a top 200 Finalist (USA) to the 1st Place Richards’ Family Trust Award during the 25th juried show at the Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, USA). In Korea, She received a growing up artist award at the Dong Gang International Photo Festival and Now and New Exhibition award at Gallery Now in Seoul Korea. Follow Sunjoo on Instagram: @sunjooleephotography

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Yi Wan Gyo: Nirvana-Beyond DarkJanuary 13th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Han ChungShik: GoyoJanuary 12th, 2026