Amanda Tinker: Small Animal

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Small Animal by Amanda Tinker.

Amanda Tinker was raised in New Jersey and currently works and resides in and around Philadelphia. She has been teaching the history of photography and 19th c. processes at Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pa, since 2001. In her process, Amanda uses large analogue cameras and 19th c. photographic techniques as a way of arranging nature, and its small beauties, into layered configurations. She makes use of the private garden, and all that it contains, to explore the balance of human creativity and nature’s own momentum. Amanda was shortlisted for the Hariban Award, International Collotype Competition in 2018. In 2020 Amanda was invited to be part of Rebel Lens at Lonsdale Gallery as part of Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival in Toronto, Canada.

Small Animal

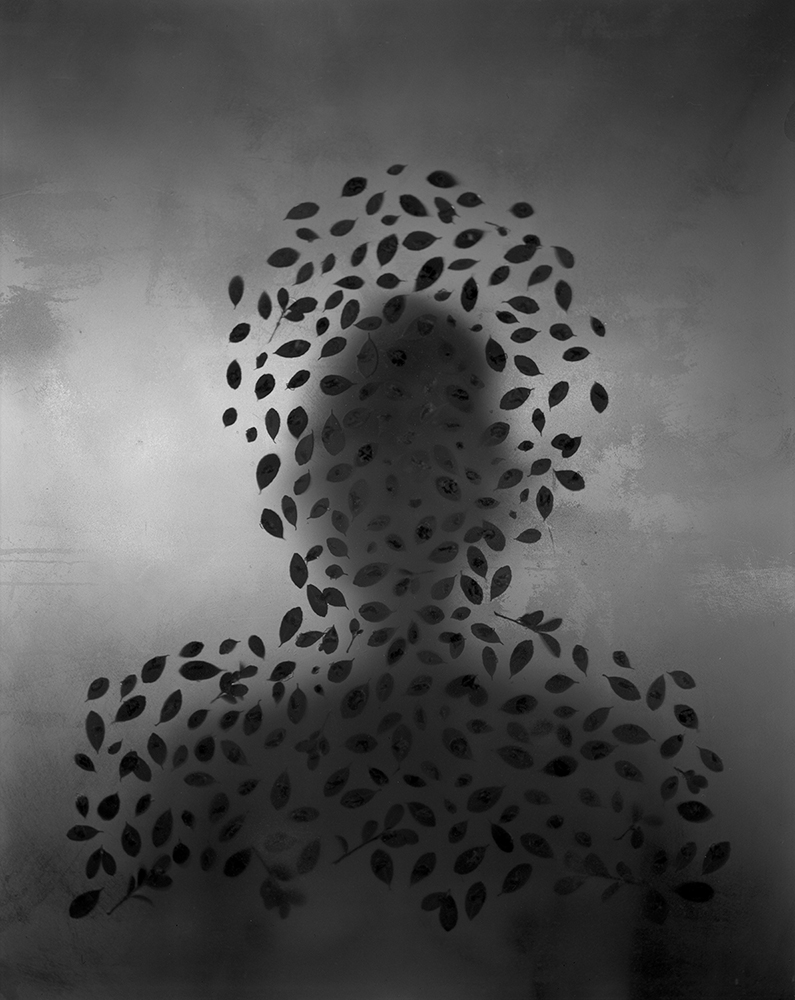

In this series of photographs, I arrange details of the natural world collected from my family garden, children’s books, and vintage identification guides. Each photograph looks at the natural world as if it were held just for our observation, suspended far from any recognizable landscape. Nature’s small beauties, such as birds, butterflies, twigs and petals become objects of contemplation, organized into layered configurations.

The 8×10” view camera used to make these photographs factors greatly into the work. The rather large piece of glass at the back of the camera, where each image is composed before exposure, offers inspiration. It is a projection screen for my interest in the early history of photography, particularly as a tool for studying nature. One can imagine an era just before the dawn of photography where views of nature stirred on the glass of a camera obscura. Nature had been transformed through optical devices giving way to a diminutive view; the landscape on a smaller, more intimate scale. This project, situated in the 21st century, reflects a more ambivalent, if not estranged, experience of the natural world.

Daniel George: What draws you to photograph the natural world, and what led to the creation of this specific project?

Amanda Tinker: That I gravitated to the natural world when I began making this work was both a function of my immediate surroundings, living and raising kids at the edge of the Wissahickon Creek in Philadelphia, and my upbringing. I grew up in the New Jersey Pine Barrens and, as the daughter of an earth science teacher, I learned to look closely at such a strange and ancient landscape.

The 8×10” view camera used to make these images also provided inspiration from the start because it has the ability to sharpen small details beyond our perception. The surface of the ground glass at the back of the camera, where the images are composed, diffuses the light, and creates a shimmering effect. It allowed me to think about how early photographers connected to the natural world through optical devices, capturing the landscape on a smaller, more intimate scale. The act of looking at nature, through the large format camera, is an experience that I try to re-create over and over in my images.

DG: This work, along with other projects on your website, demonstrate your knack for removing natural elements from the environment and recontextualizing them in your photographs. Tell us more about your interest in this process.

AT: I work very formally and bringing objects from the garden or surrounding landscape into the home gives me a way to slow down and have control over arrangement. These images offer a fantasy of nature. Different elements, some real and some artificial, are arranged together but you obviously wouldn’t find these things together in nature and not in these configurations. I’m inspired by the “impossible bouquet” of Dutch still life painting where flowers and insects and animals that would never be found together in nature, or even bloom at the same time, are painted together in lavish arrays. They are illusions generated from life but also from imagination. This intersection drives my own work, allowing me to bring together the components in any way I imagine.

DG: What is it about these delicate specimens that warrants our attention, and make them “objects of contemplation?”

AT: Beyond the beauty of these specimens, I’m trying to communicate the idea that plants are worthy subjects – in art, in science, in our lives. Particularly in this moment our relationship to plants, or how we think about the smaller aspects of nature around us, may indicate something about our relationship with nature at large.

DG: Could you talk more about your decision to include figures in the photographs, as well—and the significance of their interactions with these items?

AT: The way the figures are included communicates an ambivalent, if not estranged view of our relationship to the natural world. To me, the figures aren’t quite sure what to do with the nature that’s presented to them – and maybe they are looking at the natural world from our perspective, with both a sense of wonder and uncertainty.

DG: You write of your interests in the early history of photography. Is there an artist in particular that you feel you are channeling in this work? How do your photographs communicate with each other?

AT: I draw on 19th century photography for inspiration, particularly the early decades, because so many of the images of that era have the feeling of a first discovery. There was a deep desire to catalogue everything in nature and to show us nature in a striking new way. Both Anna Atkins and William Henry Fox Talbot were such wonderful examples of this tendency. Particularly Talbot who took interest in the magic of the process and the aesthetic quality of the images, referring to images as “a little bit of magic realized”. Photographs appealed to his imagination and even his romanticism. In the making of the image there was the feeling of something miraculous happening.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Gadisse Lee: Self-PortraitsDecember 16th, 2025

-

Scott Offen: GraceDecember 12th, 2025

-

Izabella Demavlys: Without A Face | Richards Family PrizeDecember 11th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 2November 27th, 2025