Interdisciplinary Approaches in Photography: José A. Betancourt

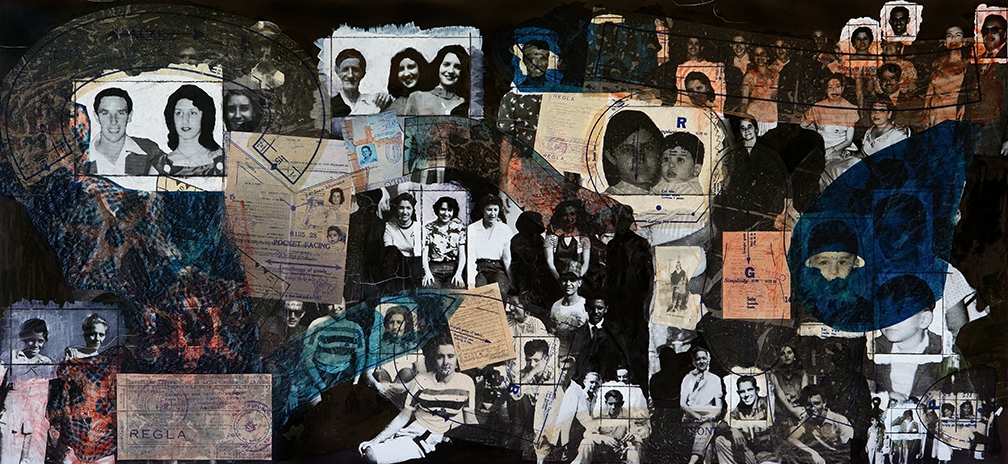

©José A. Betancourt, Expedito, 2015 Digital pigment and Cyanotype mixed media collage. 23.5” x 49”, from Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

This collage started out to show the process of choosing pictures for the exhibition and trying to identify the people in them. The technique of using white and black opaques to mask out images was used in the newspaper industry throughout the 1950s and 60s. Initially I wanted to have the look that you would have seen on an editor’s desk from the time these photos were taken.

As I discovered other information and documents it became a commentary about the people I remembered. The layering and framing emphasize my closest relatives and the clearer images are my clearest memories.

Sewing patterns were an appropriate layer because of its transparent qualities when waxed, and because of my mom’s history with handmade clothing. One of the Cyanotype patterns is from an unfinished crocheted blanket found in her trunk. I also like the reference to the sea with the shape of a starfish or even a fisherman’s net, which is an associating to my grandfather’s profession.

My parents and I are framed with a Cyanotype butterfly to represent the exit from Cuba. The Cubans that wanted to leave the country were given the name gusano, meaning caterpillar or worm, or even worse – maggot. As soon as the gusanos left they called themselves butterflies.

The title came from a photo prayer card I found in my grandmother’s trunk. I had never seen or known of San Expedito but I can guess why my grandmother had it- This was her prayer to the saint for a quick and expedited exit out of Cuba.

This week, all of the artists that I am featuring take photography beyond what it is or what it is perceived to be, to what it can be. There are a wide range of themes such as family, culture, loss, history, memories, biblical stories, mythology, film and community among others. For all of these artists, the photograph is the starting point, not the end result. Beyond photography, their approaches incorporate painting, stitching, alternative processes, object making, sculpture, installation and even community engagement. Each of them employ process and content that creates a uniquely personal style of photography that demonstrates extraordinary vision.

In 2015, I drove for 12 hours with a few friends from grad school to the Tinney Contemporary Gallery in Nashville to see the exhibition of José Betancourt’s photography called Cuba: Reconstructing Memories. Not having a well-conceived plan, we arrived at this really nice gallery in shorts and T-shirts. José was completely welcoming and thrilled that we had made the trip.

The work in that show resonated because of the way José seeks to reconstruct lost memories of the Cuba he had to flee in childhood. For example, an image of his daughter wearing one of his childhood suits is cropped at the neck, as if making this new memory with his daughter is as close as José can get to documenting his own childhood memory.

José’s struggles to return to Cuba ended in 2019 when he got to reconnect with family and document the places of importance to him as well as make new memories.

USA, Born: Havana, Cuba 1965, José Betancourt is Professor of Photography at the University of Alabama in Huntsville’s Department of Art, Art History and Design. He received his Bachelor of Arts from the University of South Florida and his Master of Fine Arts degree in Photography from the City University of New York- Hunter College, where he studied with Roy DeCarava, Mark Feldstein, Juan Sanchez, and Robert Morris.

José has been a grant panelist for the New York Department of Cultural Affairs and the Birmingham Cultural Alliance. He sometimes travels as juror for competitions and has curated art exhibits from New York City to Alabama. His latest curatorial projects bring together photography and local history to tell previously untold stories.

José’s personal art projects are inspired by documents and photography to build narratives. From the traditional documentary project to the possibilities of using objects, stories, and alternative photographic techniques to help the viewer process the information. Additionally, José and artist Susan Weil have collaborated for over 20 years on variations of alternative photographic techniques, most importantly, the Cyanotype, or Blueprint.

José’s work has been exhibited regionally at the Tinney Contemporary art gallery in Nashville, the Tennessee Valley Museum in Tuscumbia, Alabama, the Asheville Museum of Art in North Carolina, and The Baldwin Photographic Gallery in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Internationally, José has exhibited at numerous art and photography fairs, including Art Basel in Switzerland.

Follow on Instagram: @joseabetancourtpaz

©José A. Betancourt, Pionero, 2015 Digital pigment on silk. 40”x 24” , from Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

When I was 4 years old I started school in Cuba. All children of the revolution are required to be a part of the Pioneer Organization, or Organizacion de Pioneros José Marti. In my kindergarten class they were just beginning our indoctrination but one day, as my mother told the story, everyone wore the red neckerchief.

On a field trip to the fish market close to our house, my mother happened to be looking out and saw the group of kids coming down the street. Here was her son proudly wearing the symbol of the socialist movement in Cuba.

I just remember the red tie around my neck.

The pigment image on silk is taken from my actual measurements, in scale, taken from clothes from that time.

The red tie was respectfully returned to the teacher and I never saw it again.

Cuba: reconstructing memories

In June of 1971 my life changed forever, literally in a matter of minutes. With my suitcase and a toy plane, I traveled with my parents from Havana, Cuba to Miami, Florida. The flight was part of the Freedom Flights that carried over 250,000 Cubans to a new life in the United States between 1965 to 1973. Everything was left behind except what we could carry. As a five-year-old I had no idea what this meant.

I had always wanted to return to this forbidden place but for many reasons it became difficult for me to travel there. The more I thought about going back, the more memories came to me. I remember going to the beach, riding the ferry into Havana, riding the train, and watching crabs walking along the railroad tracks in front of our house. These simple, innocent memories of a child would be altered through time by other stories. I don’t remember the soldier that came to inventory everything we owned, or when they forced my father to work in the sugar cane fields- a punishment for deciding to leave the country. I don’t remember how the Committee of the Revolution watched my mother’s every move because she was against the “system”, and vocal about it. This group of photographs came from my thoughts; the initiation was from my mind’s eye. The memories of a child became complex stories of real life.

For this exhibition I chose to assemble a group of photographs that are initiated by memory. Part of my method was to write down what I remembered and apply the photographic technique that best communicated my unclear image. The pictures are usually missing something or manipulated to a surreal state. Sometimes they seem as simple as my memories.

Through the process, I found an emotional connection to actual objects and that’s why it became important to search for things that survived this time in my life. Since I had no photographs originally taken by me, I would have to shape the images from different sources. My main sources were objects of my youth and old photographs from Cuba, not just because they made my memories clearer but because I carried them close to my heart.

The techniques used to create these images have roots in the history of photography. I decided to work with a number of processes from digital to 19th century light sensitive emulsions. The Cyanotype, also known as the blueprint, has been one of my preferred techniques. For this exhibit I also used large digital negatives, 4×5 and 8×10 silver negatives, and scanned objects. The variety of techniques is what makes this journey more exciting to reconstruct.

©José A. Betancourt, El Caiman, 2015. Stitched cyanotype collage on canvas, wire inner frame. 36”x116”, from Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

El Caiman is a nickname given to the island of Cuba because its close relation to the body of a Cayman, or Cuban Crocodile. It was one of the first things that my mom mentioned when she first saw the model for my idea.

This collage has been in the back of my mind for a few years but became an essential part of my plans when my parents moved from my childhood home in Florida. I took possession of most of the pictures from Cuba and prepared to learn more about these people. In most cases I have no memories of these friends and relatives, mainly because the pictures were taken before I was born. The ones I know or remember are close family that I recognize.

The message you may find is really about identity and culture. I saw things in the photos that resonated with my memories. Playing baseball was a big part of my childhood, as were first communions, birthdays, baby pictures and outdoor activities. These family photos gave me an insight into the place; how we lived and how it looked. The images confirmed some of the things I remembered.

I chose to stitch things together to force myself to look at details. I was also using the shape of the island to help me understand the geography of the place I remember.

Greg Banks: I found a lot more information about your childhood before you left Cuba than after. What was the transition like from Cuban to American life?

José Betancourt: We came to the United States when I was 5, which is an interesting age to be dropped into another culture. I think we all learn to adapt very quickly at that age. The biggest obstacle was learning the language, and schools back then were not prepared for helping kids with English as a second language. That first year was rough. My mother had to pick me up from school many times because I just couldn’t understand what was going on and would do my own thing. Including playing drums on my desk.

I learned quickly. I say that because I think by second grade I was doing much better.

As far as keeping our culture intact, we were able to live in a neighborhood with many other Cuban immigrant families and we always spoke Spanish around the house, ate our traditional foods, and were able keep family traditions because we had most of my mother’s extended family in the same area as well. Even though I adapted well as a kid, I was always aware of the cultural differences. I have always been aware of assimilation, even as a teenager, but I seem to be analyzing it now more than ever. When I was younger I was just going along with fitting in, but as I got older I started understanding that it wasn’t exactly who I really was.

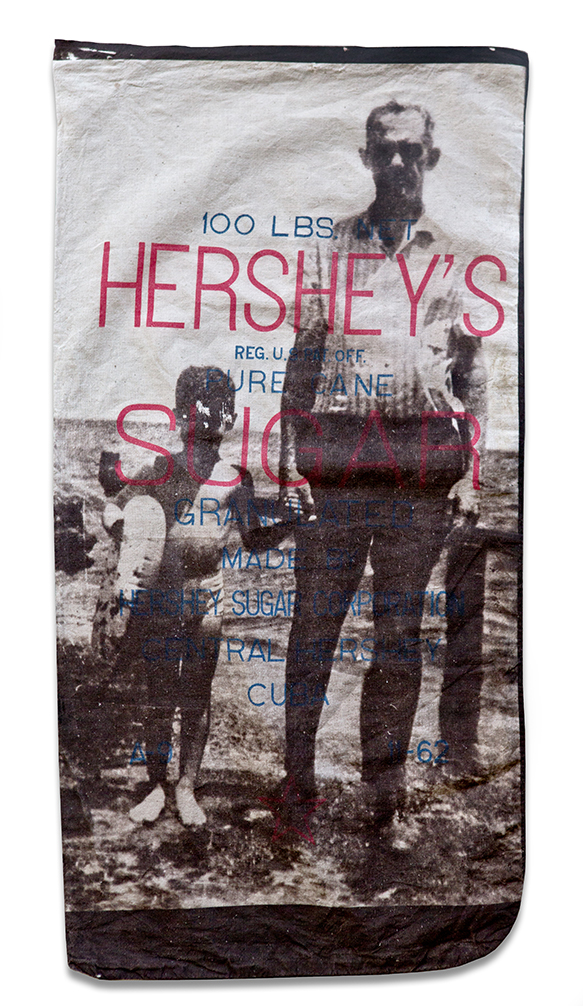

©José A. Betancourt, Casablanca to Matanzas, 2015 Van Dyke Brown on vintage canvas sugar sack. 39.5”x 23” , from Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

The process of getting out of Cuba during the 1960s and 70s was not easy. For most Cubans, we had to find a sponsor. My aunt Ofelia, who lived in New Jersey at the time, applied for our sponsorship and we all waited until our name was called. A lottery of sorts which also gave the family a number for departure.

During this waiting game the government set forth their guidelines. My mom tells the story of a green fatigued soldier coming to the house to inventory all our belongings. We were to leave everything behind and there would be a list.

Another mandate was that my father would have to take a manual labor job. This was seen as punishment and quite possibly a deterrent to others. After helping install water pipes in the city, he was sent out to the country to cut sugar cane. During this time my father had to stay at the sugar cane fields in the area known for the Hershey sugar cane plantations, Matanzas. The train ride from the town of Casablanca to visit him in Matanzas is one of my memories from this time.

It seemed most appropriate to print a picture of my father and me on a 100-pound vintage Hershey sugar cane sack from Cuba. Taken in Cojimar around 1970, this is the only picture I have of the two of us during the time of these events.

GB: You just got back from the Canary Islands where you were researching your family history. What would you like to share about your trip?

JB:As you know, I am still processing everything. There is so much to tell. The most important part of the trip was to try to piece together a story that nobody knew much about. My father never knew nor could remember his grandparents and I always thought that was odd. I remember you and I talked about this because you had a similar experience. Many people have a mysterious family story but never act on solving it.

When I went to Cuba in 2019, I was able to reconnect with many family members who knew some details of this story. As I spoke with them and others here, what intrigued me was that the stories were never the same. The common part of the story was that my great grandmother and her siblings came from the Canary Islands to Cuba without their parents.

Long story short, I found a tree on Ancestry that took me to another branch of the family. Once I got the names from that tree, I was able to find a blog written by someone in Tenerife about Charles Piazzi Smyth, the Scottish Astronomer Royal and photographer who travelled to the top of the Teide volcano to look at the stars and planets from a high altitude. Incredibly, the historian mentions my great great grandfather in the same blog entry. He also includes a copy of the census of 1875 and there was my great grandmother at two years old with her siblings. This blog changed everything for me. This same historian later wrote about my great great grandfather at the worst time of his life. After achieving so many admirable things in his life he decided to go along with a friend and rob an Englishman working on the island. They ended up killing him and less than three years later they were both executed by garrote vil. So, as you can see, all this needs to be told somehow.

©José A. Betancourt, La Lanchita de Regla, 2014 Cyanotype on paper. 21.25” x 39.5”, Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

I have a vague memory of riding the ferry (La Lanchita) from Regla, where we lived, across the bay to Havana. The lanchita seems to have always been a part of our family. My grandfather was the ferryman for many years and also worked on commercial fishing boats through the Straits of Florida and up to Ybor City in Tampa. My grandfather died shortly after I was born and have no memory of him but I always relate this image with him.

The lanchita was also in the news in 2003 when three men tried to escape the island on one of these boats. The ferry ran out of gas, the men were captured and later executed by firing squad. I remember feeling more disturbed by this event because of it being from my hometown and a part of my grandfather’s history.

GB: I think it is interesting you do not have documents of your early memories and then you choose to be a photographer. Does the photograph play a role at all in confirming memories of your birthplace?

JB: When we left Cuba, we weren’t able to take anything except our suitcases but I do have some things to work with from that time. I made a photograph of the suit I wore on that day. Another thing I have from that time is a toy plane. I believe these personal objects can help initiate a story about your history. And in the case of the plane, I used it as a way to tell the story of the Freedom Flights, which was the historical event that helped us get here. There are usually many layers to each piece, like an archaeologist who finds something and begins to piece together events to create a narrative of the object. Since we didn’t bring much, some of the stories I chose to tell were from objects, including family photographs, that made it back to us through the years. The photographs as objects have become very important to me. One photo of my grandfather became the metaphor for the entire Reconstructing Memories project because an insect had eaten the emulsion of the print and his face was completely gone.

Memories and stories initiate the process and then the research begins. My latest work is based on the object and the most truthful text I can find. The words are sometimes more complicated than the photograph because I spend hours trying to find the most accurate story. The photograph could be from a simple scan of objects to a complete photo illustration manufactured in photoshop. I guess to answer your question, yes, the process helps me confirm some of the details in my thoughts. I always see the photographs from this series as illustrations rather than actual documents. They help illustrate the story, not show an actual moment. The text is what makes them more of a document.

©José A. Betancourt, Departure, 2015 Hand colored gelatin silver print. 49”x39”, Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

Most of the women around me when I was young liked knitting and sewing. My aunt and my mother were both seamstresses and my grandmother liked to knit and stitch blankets. It was also a normal thing to take old materials to make new things. One of my mother’s friends made this suit from one of my grandfather’s old suits. Most, if not all of the clothes I have from this time were all hand made.

I wore this blue suit on our departure day, June 15th, 1971. My five-year-old daughter, same age as when I wore this, is my model. I seem to be living my memories in some association to how she lives as a five-year-old. Her interests and her interaction with her surroundings make me wonder about how I was at this age.

The hand-tinted black and white darkroom print seemed appropriate to have the viewer travel back in time to see me dressed up and ready to go.

GB: Talk about how not getting to travel to Cuba led recreating those early memories from only a suitcase of belongings?

JB:My sabbatical was approved and I thought it was the perfect time to travel to Cuba. Especially after the Obama administration reestablished relations. My main obstacle was getting a Cuban passport to travel back. I am a naturalized U.S. citizen but I found that anyone who came from Cuba after 1970 needed to have a Cuban passport to travel back. As I stumbled through the process, I found that there was no way to get there in the time I had for my sabbatical. I had a difficult time with this in many ways. My main disappointment was that this was also supposed to be a trip back with my father and now this would not happen. The initial project was to revisit my memories with him. It was going to be more of a collaborative documentary style project where I told stories of what I remembered and went in search of them together.

In the end, the only regret is not traveling with him. The rest is a blessing because I made important artistic choices that brought a depth to my work that I didn’t expect. The work was initiated by my personal memories and then I continued with interviews of my parents, family, and friends, to find the commonalities and what could be accurate. This was the beginnings of the process that I’m using today.

©José A. Betancourt, Freedom Flight, 2012 Cyanotype on canvas. 68”x112”, from Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

In June of 1971 my life changed forever, literally in a matter of minutes. With my suitcase and a toy plane, my parents and I traveled from Havana, Cuba to Miami, Florida. The flight was part of the Freedom Flights that carried over 250,000 Cubans to a new life in the United States between 1965 to 1973. Everything was left behind except what we could carry. As a five-year-old I had no idea what this meant.

I can’t say I remember where I thought we were going. I had an idea that it had to do with seeing my cousins again. They had left in the flights in 1968. I do remember being at the airport playing with my plane. My mom says all the kids waiting to leave that day were playing with me because I had brought my plane. My mother always told the story of how the plane could have easily been taken away by the guards because we were leaving. They were known to take things from the passengers because of their contemptuous choice to leave their homeland.

I wanted to use my plane for a piece in this series and the most appropriate way to use my toy was to represent the plane that brought us here on that day.

GB: You had a lot of difficulty returning to Cuba but you finally had the opportunity to return in 2019. What was that experience like? Were you more focused as a result of having to recreate your own memories of the place?

JB: I was extremely focused. I had studied 40 years of materials and when I returned it felt like I had just left. This feeling was supported by the fact that Cuba has been in a time capsule for the last 60 years. My cousins were the same, just older. The family was close and welcomed me as though I had never left. This has to be the closest experience to time travel. Many Americans who visit see the old cars and the architecture and comment on how time stood still. But can you imagine having lived there as a kid and visiting your old house, and walking the same streets 40 years later? That is an extra level of time travel.

While I was there, I had a list of things I needed to accomplish. But mostly, I was open to being with family and documenting things along the way. This reconnection with family in Cuba has been the most important thing for my work as an artist, but also for partly filling the emotional loss of my parents.

©José A. Betancourt, Regla’s Gift, 2015 Digital metallic c-print. 30” x 20”, Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

This doll was my grandmother’s good luck doll while I was growing up. I wanted to photograph it wearing my gold Caridad del Cobre necklace that I’ve had since I was born.

I remember seeing these images and hearing stories on Santeros, the priests of the Afro-Cuban religion of Santeria, throughout my childhood. Although religion is not promoted in communist Cuba, it thrives in many ways. Catholicism and Santeria both survive with many followers.

Santeros usually wear all white and Regla, my town, is known for their religious practice. Wearing white can also be a reference to the Ladies in White, or Damas de Blanco, a group of women in Cuba protesting imprisoned dissidents.

Loaded in cultural symbolism for some Cubans, my photograph may be construed by some as a derogatory image or a black face doll. It is important for me to connect with the viewer in a way to help understand these conflicting views while keeping

the integrity of my memories.

GB: Talk about your process and how you decide to make the work?

JB: The Cuba series, entitled Reconstructing Memories, is the one that started the process of image and stories. First, I wrote things I remembered from Cuba, mainly as a five-year-old. During my process, and interviewing people who may have been a part of the memory, I found my earliest memories were probably from about three years old. It was really an interesting exercise.

It all started out as a simple list and later I would write notes from my interviews to corroborate what I remembered. As it came together, I wanted to find the best photographic technique to help enhance the image. For example, if anything had water as a memory, I would consider the Cyanotype as my technique. This is a technique that I have worked with the most in recent years with my collaborations with Susan Weil. Cuba has a very deep soulful connection with the color blue; from the dress of the Virgin of Regla, the patroness of the town where I lived, to the colors of the houses and the sea.

When I was telling a story about an object specifically, I would use a photograph or scan of the actual object and decide how to best illustrate the story. This was the technique I used to bring my grandmother’s saints to life. They were small statues used on the dash of a car but I chose to make a larger print that brings them to the scale of church icons.

In the photo of my suit, I considered the Cyanotype because it was a blue suit, but something else came to me that really would make an impact for the viewer. My daughter was five at the time and I thought she could be the perfect stand in for bringing the suit to life. I wanted it to be bigger than life so I photographed her wearing the suit with my 8×10 camera. I then hand colored the suit blue on the large black and white print. After I started using different techniques to tell my stories, I actually started to push myself to consider using as many techniques as possible. So, I ended up with blueprints, brown prints, wet plate collodion, scans, etc. I also used appropriated digital images, and shot 4×5 and 8×10 cameras. It was exciting for me to produce a show with such a wide variety but I also wanted it to be an exciting experience for the viewer. I thought this would help them remember my stories.

©José A. Betancourt, Mima’s Saints, 2014 Digital metallic c-print. 24” x 36”, Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

My family is catholic and we come from a town where the patroness is celebrated every September 7th by carrying her statue through the streets of Regla. The virgin of Regla, the black Madonna, is also called Yemaya in the Santeria religion that blends together Catholicism and African Yoruba. The uniqueness of this virgin comes from the black Madonna carrying the white baby.

The patron saint of Cuba is Our Lady of Charity (La Caridad del Cobre) and is always shown with the canoe or boat with the “three Juans” who first saw her image in Cuba.

Images or icons were always a part of my surroundings. As far back as I can remember I had the image of the Madonna in my bedroom growing up. I found these and the icon of St. Anthony in my grandmother’s trunk. After she passed, all of her belongings were put into two trunks containing clothing, material for sewing and knitting, photographs and other personal objects.

These were made to go on the dashboard of cars and are only a few inches tall. I scanned them to give them some size for a closer look but also to give it a new context. They weren’t made to be seen with all their flaws.

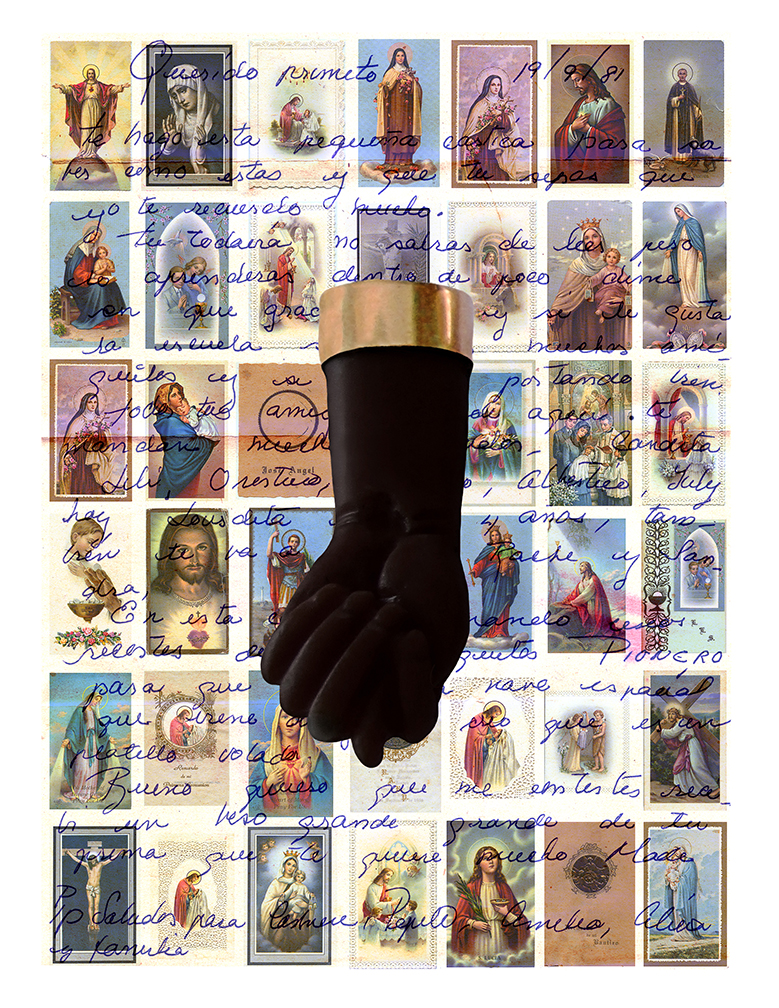

©José A. Betancourt, Change of Fortune- Mano Figa, 2018 Digital collage pigment print. 24”x 20”, Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

The Mano Figa has powers of protection and good luck. The complexity lies in its meaning throughout its long and wide-spread history. It is vulgar in many cultures but was used as a symbol of Christianity in the New World. Growing up with many references to religion and traditions makes it an interesting combination of prayer cards and multi-ethnic symbolism. This amulet, and the similar jet black Azabache, are worn by small children to ward off the evil eye. I lost my Azabache that I brought from Cuba and have never forgotten its meaning. The faint writing is a scanned letter from my cousin who was wishing me good fortune in my new home.

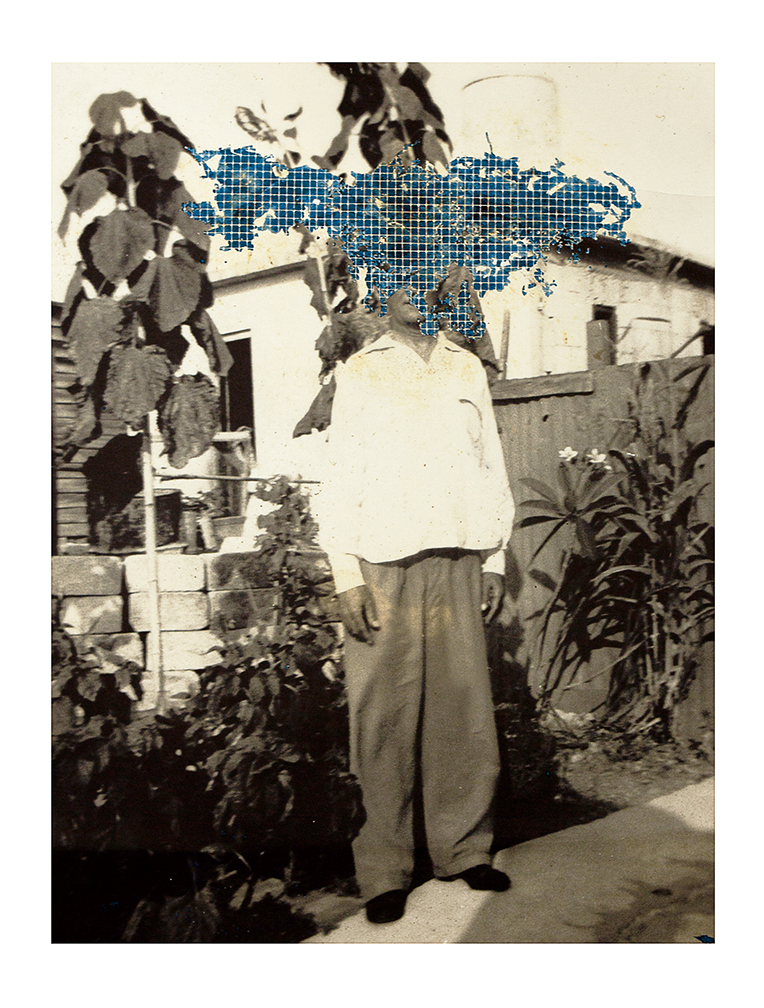

@José A. Betancourt, The Revisit, 2012 Cyanotype and digital pigment on paper. 30”x 24”, Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

A few years ago, my cousin travelled to Cuba and brought back some pictures of my dad’s family. For me, I can’t fully express into words the feeling of discovering old photographs that I’ve never seen. It is like bringing life to a new time in my family’s history.

This photograph was in a group of pictures taken in the 1950s outside of my father’s family home in Regla. Some of the pictures had water damage and a couple had this strange random pattern. After a closer look I noticed it must have been caused by an insect. The photograph came to me at the time when I was thinking about a project on my history and identity. This was the first piece I created to revisit my memories of Cuba.

I liked the idea of using the word revisit as a noun for my future plans but also to describe the process of the insect. It had to eat in a certain way to make this strange pattern and would have to go back over and over to completely devour the surface of the print. The randomness of the process and the fact that I could not see my grandfather’s face became the metaphor for my process of remembering.

I also thought of positioning a grid as a way to make order out of chaos. In this case, the process of putting things somewhat back together. Painting the Cyanotype and following the damage made by the insect also formed an interesting visual effect of a dense cloud keeping me from seeing my grandfather’s face.

©José A. Betancourt, Ñañigo, 2016 Wet Plate Collodion on aluminum. 4”x5” (framed 8”x10”) , from Cuba: Reconstructing Memories

The Ñañigos, or the Abakua, are derived from Nigeria culture and are also associated with the town where I lived in Cuba. These street dancers communicate with the spirits. All of these symbols of faith represent religion as a combination of African and European beliefs. Talismans, amulets, rituals, and fortune-telling continue to be a part of Cuban and Latin American culture. These were not only characters from myths and lore, they were friends and neighbors throughout my childhood. The richness of the collodion image and its tones was something that seemed appropriate for these characters from a mysterious Cuba.

Greg Banks is a photo-based artist and lecturer at Appalachian State University. He received his MFA in photography from East Carolina University in May 2017. He received a B.A. in photography and a B.A. in fine art from Virginia Intermont College in 1998. Greg combines everything from IPhone images to historic 19th century processes, gelatin silver printing, painting and digital printing. His current creative practice investigates family, folklore, memories, magic, history and religion in Appalachia.

Follow Greg Banks on Instagram: @gregbanksphoto

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026