Lieh Sugai: Kiseki

For the past few days, we have been looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Lieh Sugai and I discuss Kiseki.

Japanese-born Lieh Sugai is a New York visual artist who works with photography and video. Her subject matter is comprised of memories that occur between people and places, and how these are shaped by time, events and culture. To explore them, she uses her dual perspective as a Japanese immigrant whose home is also in America.

Lieh studied Graphic Design at Pratt Institute, where photography became her prevailing passion, as a way to enter, express and document different cultures, and to push the boundaries of her creativity. Her work has been exhibited at Foley Gallery and others around New York City, as well as internationally.

Kiseki

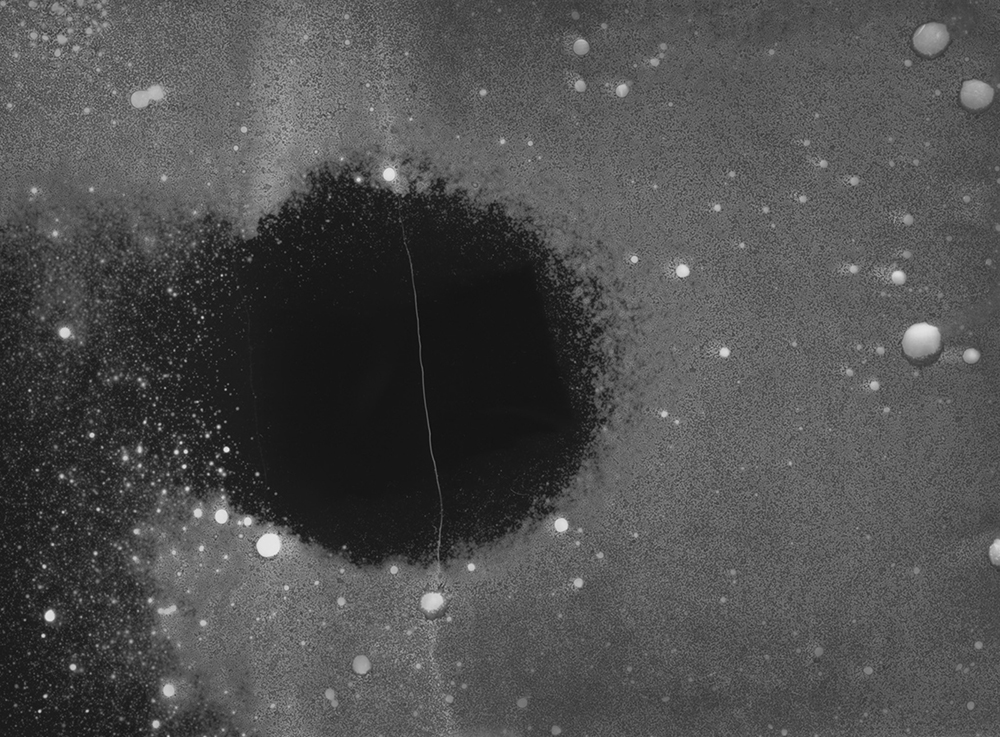

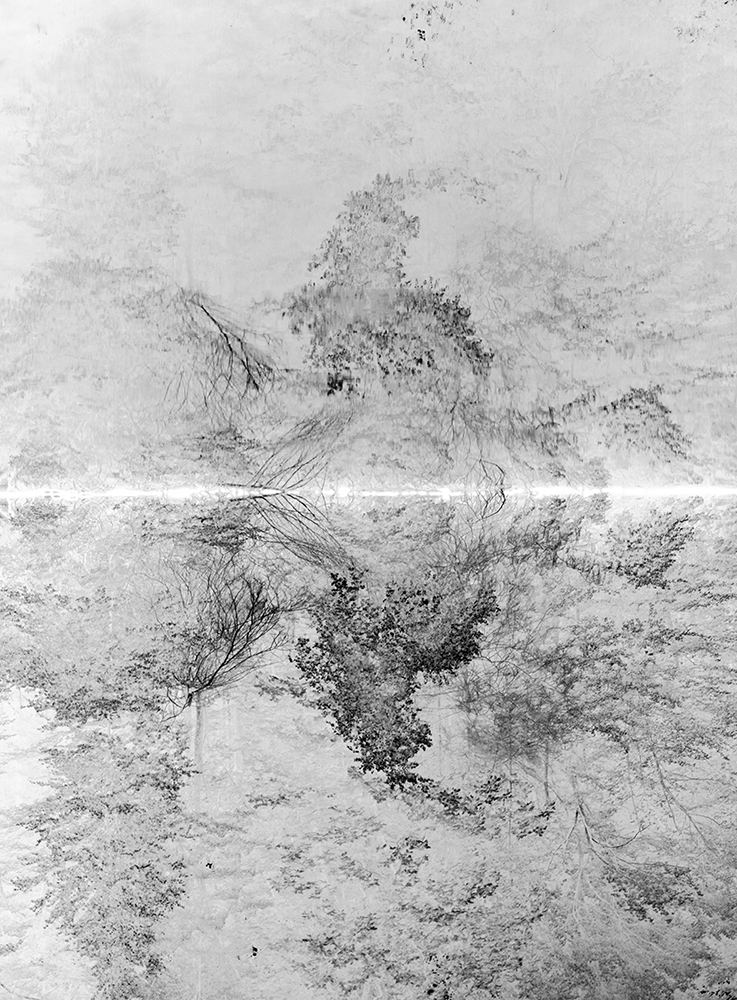

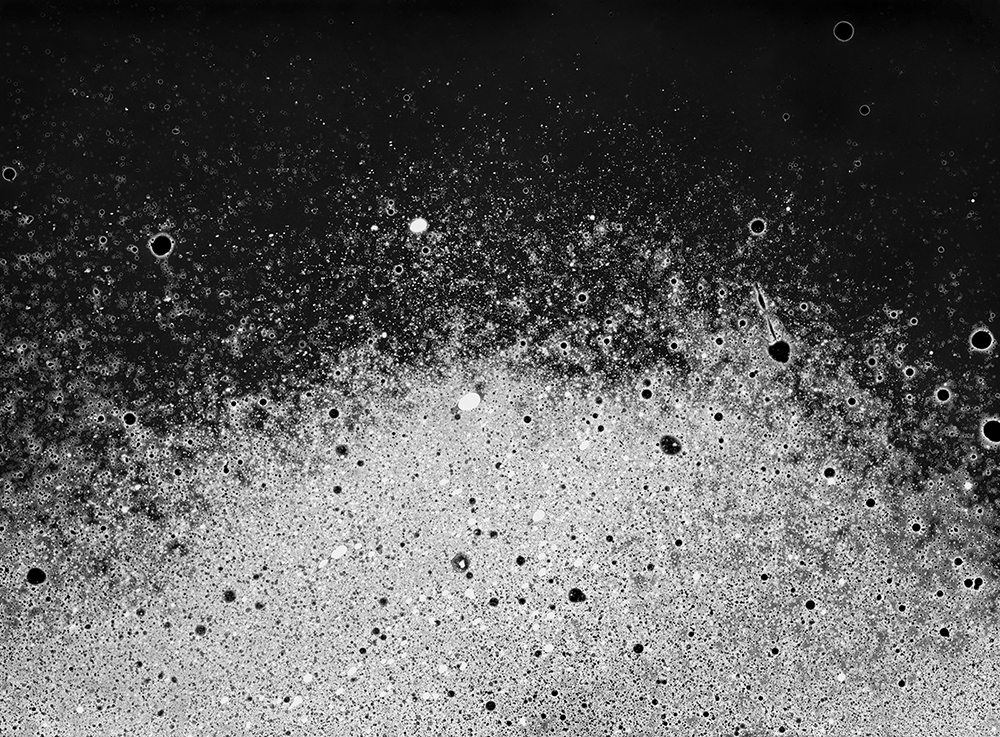

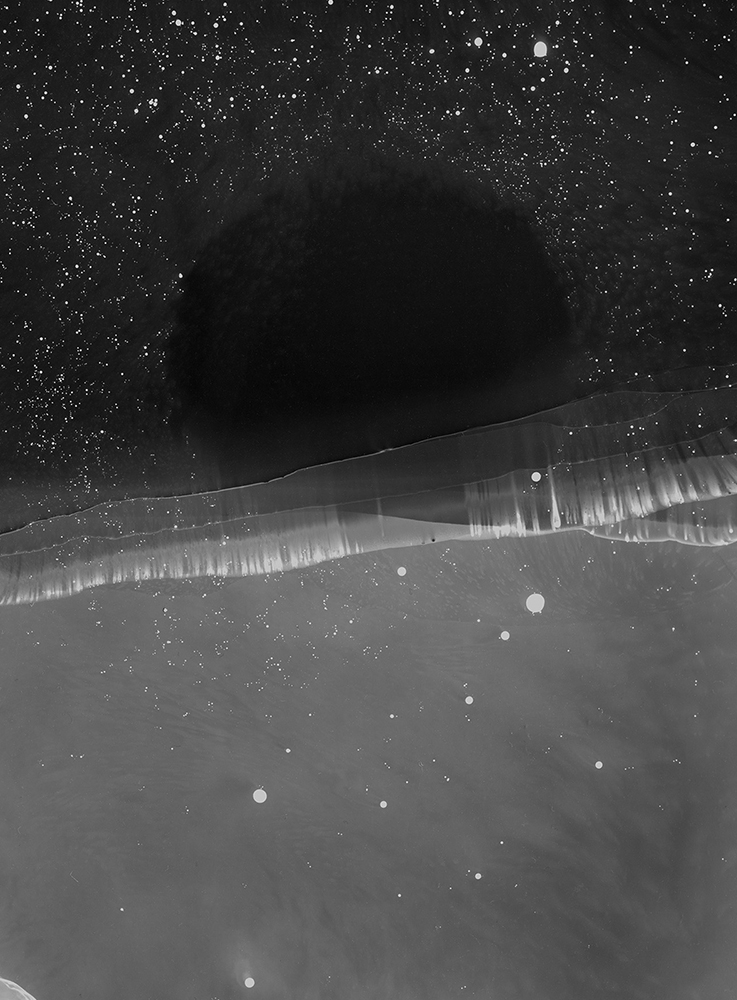

KISEKI—meaning ‘trace’ in Japanese— is a collected work of photographic images and a historical photographic process, chemigram, which I utilize to create reactions between the photographic paper and photographic chemicals.

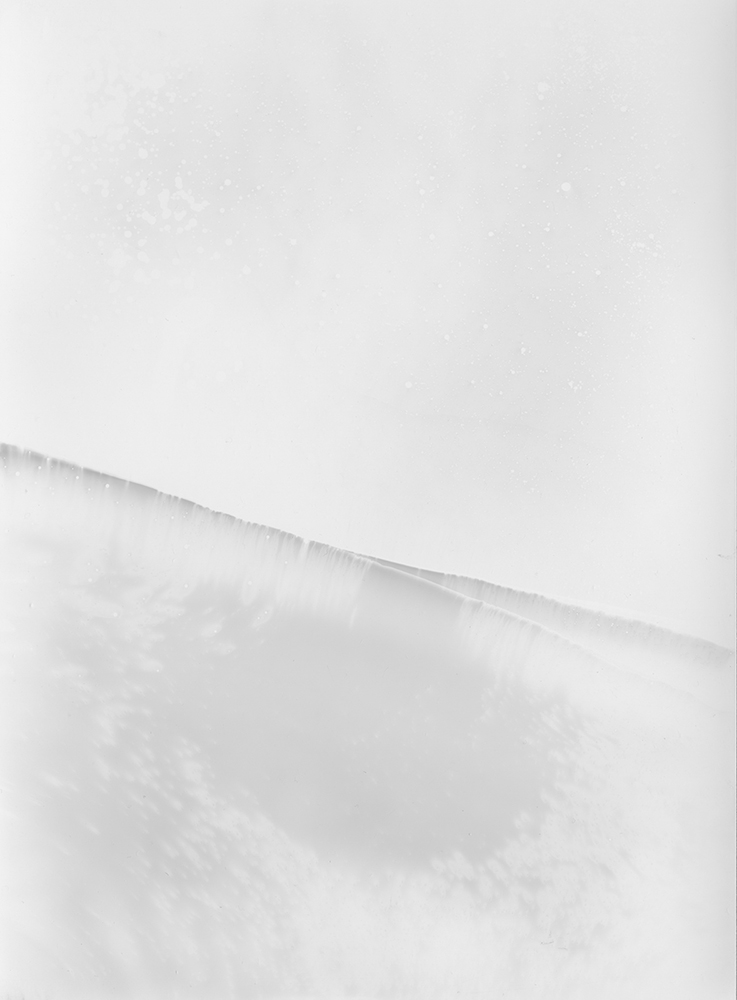

These images were created in and between my two homes, in Japan and America, over the course of years, mainly during the past few years. While KISEKI became a reflection of reminiscence and nostalgia toward my home country during that difficult year, the work is much more than that: it is a spiritual journey populated by memories that surface between reality and illusion. It is also a reflection of a feeling of emptiness, surrender and acceptance to a greater and larger force or power, such as nature and the universe.

In KISEKI, following the path of lights and shadows, I am searching for evidence of the existence of my home in my own fragmental memories.

Daniel George: I’m curious about that time you spent traveling and living between Japan and the United States, and what led to the formation of this project. What prompted you to begin making work about your experience?

Lieh Sugai: I moved to New York over twenty years ago, from Japan. During the difficult times in the past few years, many people, including myself, who live away from their family were not able to see them for a long time. For me, the way to deal with the situation was to create something from that experience. I started looking for familiar subjects in America that remind me of Japan, and that is how this series originally started. It became a reflection of reminiscence and nostalgia toward my home country and I titled it KISEKI—meaning “trace” in Japanese—the creative process was similar to collecting memories and putting the pieces together and creating a path that led to the place where I wanted to be at the time.

DG: Tell us more about your fascination with the chemigram process. What drew you to it, and is it something you will continue moving forward?

LS: I started experimenting with chemigram during the pandemic, after I created a DIY darkroom in my apartment bathroom. The process is simple but the result was unexpected. It is a chemical reaction between photographic paper and photographic chemicals, and I found it interesting because the uncertainty of the chemical reaction reflects the feelings and emotions that we had at that time, during the pandemic—we didn’t know where the whole situation would lead us, especially in the beginning.

I now go back working with the camera more, but I want to continue experimenting with this historical photographic process because, in a way, I see it like painting and I enjoy the process of creating something unexpected.

DG: Your images in this series vary in their level of abstraction—from a simple use of black-and-white, to wholly non-representational. I am interested how this relates to the theme of reality and illusion of memory. Would you talk more about the significance of including both these types of works?

LS: I wasn’t sure if the simple photographic images and abstract images including chemigram would work together as a series in the beginning but when I think about the core of this project—memories and nostalgia towards my home country—I was working to put together various fragments, to fashion a kind place constructed of memories. These non-representational images do reflect my actual memories, especially older ones, but the way they surface takes place somewhere between reality and illusion, like a dream. I found that they could be presented as different time periods of my memories and brought together into a collected work.

DG: You describe this project as a spiritual journey and a reflection toward your home country. What sort of discoveries did you make about notions of home throughout your creative activity?

LS: The last few years were a trigger for this project, but during the creative process, I realized that these emotions toward my home had been building up over all the years since I had left Japan, more than twenty years ago. It was interesting to find this out because I always wanted to live abroad when I was young and since moving to New York had never really missed home—or I should say, never felt the same way that I have recently.

I think that the pandemic changed my way of looking at things and made me reevaluate the things around me, including my family. And so while the creative process was both a spiritual journey and reflection toward my home, in a way it was also about self-discovery.

DG: You write that, “In KISEKI, following the path of lights and shadows, I am searching for evidence of the existence of my home in my own fragmental memories.” Do you feel that the photographic medium has a specific value in unlocking a sort of greater understanding? What do you suppose that might be?

LS: I think the photographic medium does have a specific value in evoking understanding in us, because of its ability to speak to our instincts, in a kind of echo of our capacity to see and interpret the world, and ourselves. The visual can explain without a thousand words, and though this series is very personal and subjective and it could be hard to grasp what it’s all about in the absence of words, there is nevertheless something recognizable—I hope—in the sense of unknown-ness or uncertainty that are reflected in my scattered, fragmented memories and emotions, if that makes sense. There is my story behind it all, but I would be happy for viewers to come up with their own interpretation of this work as well.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026