Chris Maliwat: Subwaygram

At the 2022 Medium Festival of Photography, I was fortunate to sit across the table from Chris Maliwat, where I learned about his years-long project, Subwaygram. I was (and continue to be) intrigued by the breadth of this project, and the empathetic lens through which he recorded his subjects. This year, Chris published this series with Daylight Books. Today, I am happy to share a conversation we had about the work.

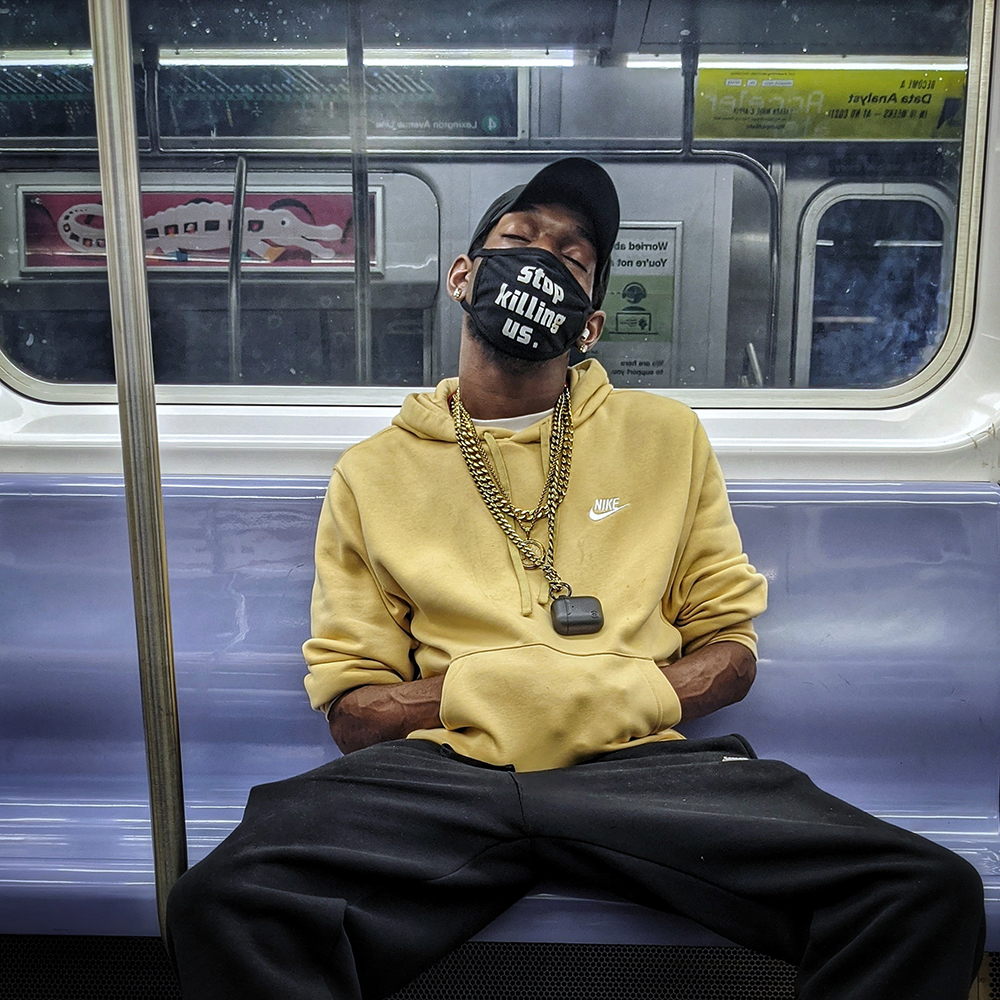

Chris Maliwat is a Brooklyn, New York based street photographer who captures surreptitious moments of everyday people on their journeys in the cities where they live. In a world where people consciously and often obsessively cultivate an image to portray, he takes candid portraits—often without being noticed by the subject—to show how people look when they are unposed and unmasked.

Subwaygram

Subwaygram captures hundreds of street portraits of the diverse community of riders two years before and two years after the first COVID case was confirmed in New York City. Complete strangers find a common place in the subway. Wall Street executives, Brooklyn millennials, and newly arrived immigrants, from all different boroughs, collide on crowded platforms and share an intimate space underground in a way that doesn’t happen above ground.

Daniel George: First off, congratulations on the book! What a great culmination of this work. Tell us more about the beginnings of Subwaygram—when you first began photographing fellow riders. From my experience on public transportation, there is a tendency to focus inward and tune out everything around me. What made you want to pay attention outward?

Chris Maliwat: I took my first subway portraits while living in Japan in the late 90s. I was living in Tokyo as a part of a college study abroad program. It was the first time I had lived in a big city and I was fascinated by how integral public transportation was to the life of the city. The cobweb of lines were the arteries underlying every block and the trains pulsed, delivering the 14+ million citizens through the vast body of the sprawling metropolis.

At first, I did turn inward – burying my head in books during my daily commute, occasionally drifting into a daydream while thinking about what lies ahead or nothing at all. And then something shifted, I started to observe my fellow passengers in their own liminal states, somewhere between two physical spaces and mid-thought.

I became obsessed with capturing those moments, yearning to understand what stories were running through their heads.

(you can see some of the photos from that original work here)

DG: This is a pretty broad question, but how did your way of thinking about these photographs evolve during the pandemic? And over the span of the past several years of making these images, how did you develop in the ways you thought about all this?

CM: When the pandemic hit New York City, like so many others I stopped taking the subway entirely. We were wearing gloves and masks at the grocery store and wiping down our mail and I couldn’t fathom feeling safe on the trains for a long time. When I did start riding again, the level of anxiety and hesitation in the air was palpable. I could feel it in how I held my shoulders and the way I took shallow breaths while passing others. I saw it in how people interacted from a distance, like repelling magnets dispersing in the cars. I found it really disorienting. Before the pandemic, I would complain about packed trains but it felt like we were all experiencing it together and there was safety in numbers. COVID weaponized our breath in a way, and the camaraderie one used to feel on a train full of strangers collapsed into more like a minefield.

It felt important for me to document this time in our history, as we navigated personal safety in a public space. It became a bit of a daily meditation for me, it helped me remember that we’re all in this together and we’re not competing with each other.

DG: I’m curious about how you work. Do you only photograph those individuals who sit nearby? Or do you move around inside the train—drawn to certain people?

CM: For this series of work, I only took pictures as a part of my daily commute or as I was heading to and from my apartment to meet friends or run errands. It felt important to me to capture images as a participant, as a fellow passenger, and not as an outsider. I generally photograph folks that I sit close to. There’s often some kind of energy, an aura almost, something emotive that I sense in people that I’m drawn to. It’s hard to describe but I guess I’ve trained my eye to notice people who have expressive faces or body positions. They make me want to lean in and learn more about what they’re thinking about.

DG: What is the allure of the “unposed and unmasked” portrait?

CM: In a world where selfies are the norm – where all of us have predictable poses and smiles when confronted with a lens – I craved a way to observe and capture the authentic essence of people. There’s an earnestness and vulnerability that attracts me.

DG: One component of these images that I find compelling are the smaller vignettes contained within the oftentimes crammed frame. Could you talk more about the importance of the gesture and expressions of your subjects in these photographs, or those ways in which you found (as Aaron L. Morrison writes in the book) “commonality with fellow riders?”

CM: Walking on the subway, it would be easy to miss or ignore all of these vignettes and turn up some random podcast or binge some downloaded show. I seek out these stories, I think, because I find it incredible how revealing even the slightest gestures can be to convey the full spectrum of the human condition. It makes me feel more connected and constantly reminds me of how fantastically diverse this city is. It makes me feel like I belong here.

DG: Did you envision the project in book form? What was the process like taking it from Instagram and translating into something physical?

CM: I didn’t. Instagram provided a great feedback loop for the project and helped me hone my process and visual style. My previous projects were B&W 35mm film, so this was a big shift for me. Translating the ‘feed’ into book form was a challenging and fun process. There were some elements I wanted to preserve. I kinda like the intimacy of scrolling through photos on your phone, I enjoyed the challenge of expressing a lot in a tiny square. I had a lot to learn about visual pacing and establishing a narrative arch. I produced a lot of book dummies, spent a lot of time arranging and rearranging little squares sprawled across my living room floor. It was terrifying and ultimately really satisfying to produce something that has a beginning and an end. I was shooting photos right up to the final month or so of the final edit… There’s a finality that the physical book form forces you to confront.

DG: What insights can you share about the book making process—for those interested in pursuing publishing their work?

CM: I had a pretty narrow definition of what I thought was possible at first. I really became a student of photobooks, spending hours flipping through books from the vast canon of photobooks. I would take note of how each book made me feel and what I deciphered as the mechanics to achieve those feelings. It really helped me find and refine my own artistic voice. I also found it very useful to seek feedback through portfolio reviews and critiques. Those experiences required me to articulate my intention in words and ultimately helped guide the edit and final form.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026