The Human Experience Through Alternative Processes: Tina Rowe

“One way or another, we all have to find what best fosters the flowering of our humanity in this contemporary life, and dedicate ourselves to that.” – Joseph Campbell

An idea I have constantly grappled with is the idea of humanity. How is it each human being experiences similar events yet each of us is entirely unique? Due to my curiosity about how others perceive this question, I have interviewed artists that use particular photographic processes to dissect the idea of what it means to be human.

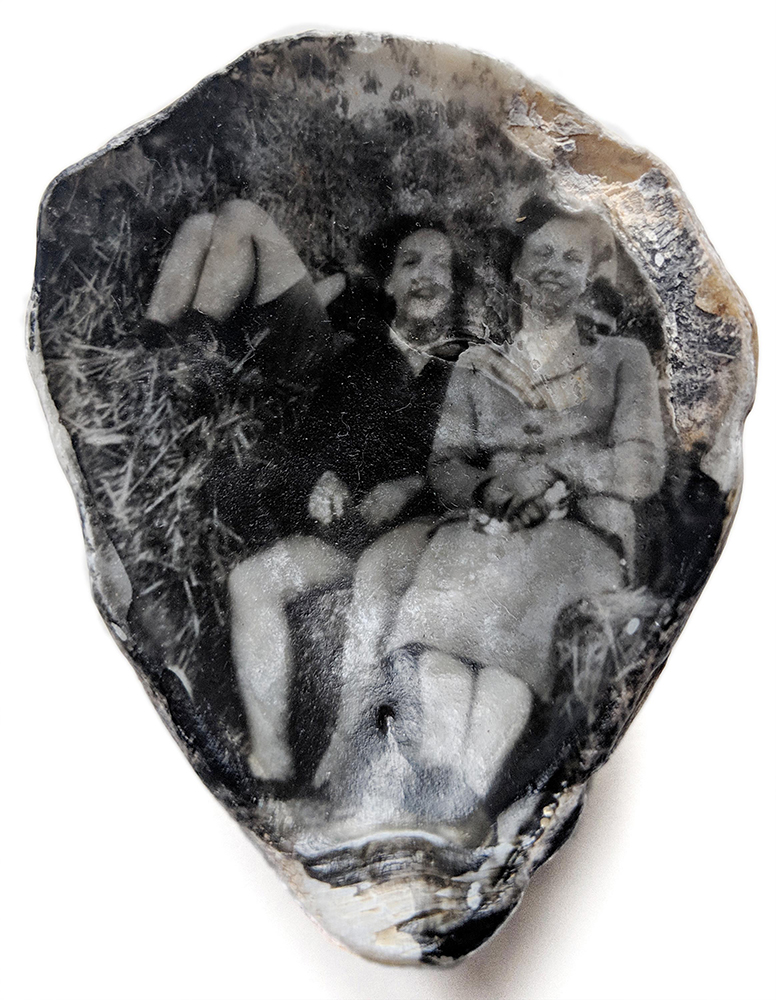

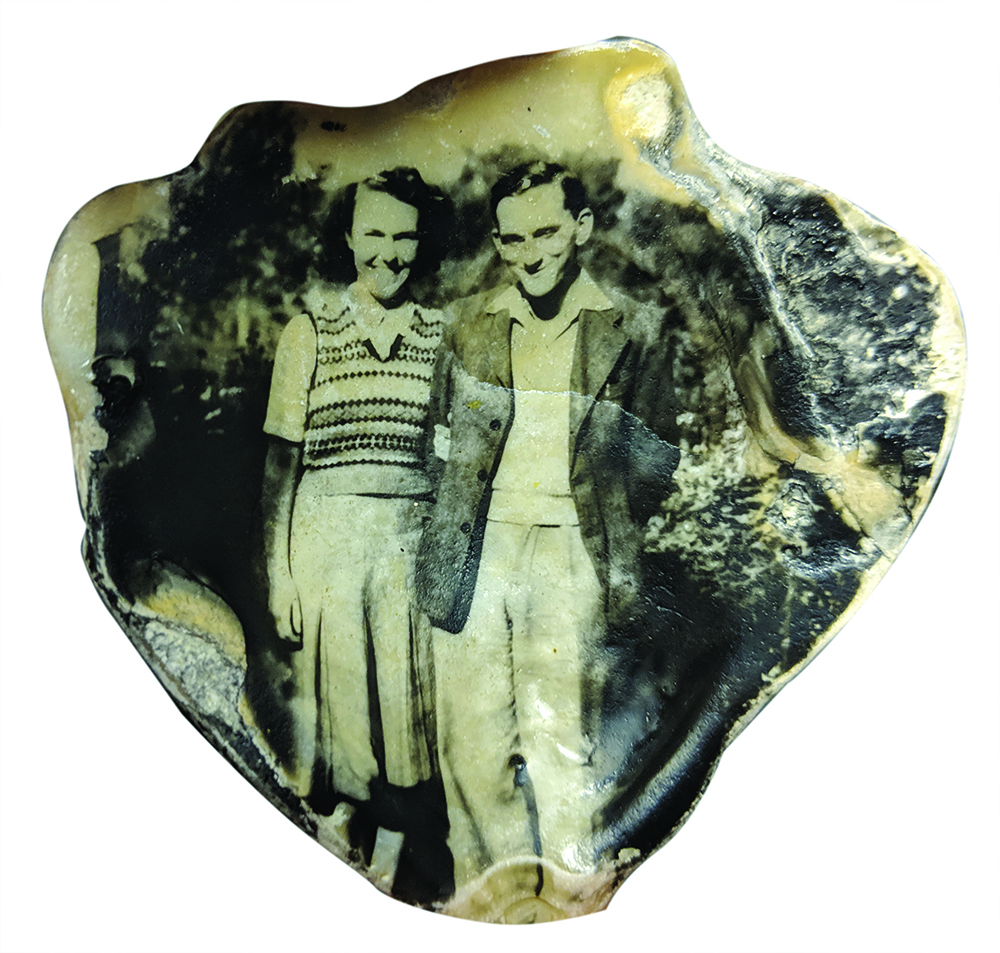

Tina Rowe‘s use of collected shells and appropriated found film photos paints a haunting yet intriguing picture of the lives of those past. In each piece the natural decay of the shell mixed with the way the emulsion has been poured, evokes the lives of each subject. We know nothing of these people yet as we look at Rowe’s work, we see a glimpse of their lives and who they may have been.

Tina Rowe works with the tools of analogue photography to explore the ways that human presence is recorded and lost in the landscape. Her work makes use of the material possibilities of light sensitive chemicals on different substrates. She is particularly interested in early processes and is a founder member of e5process darkroom, which was set up specifically to support artists who use film photography.

Follow Tina Rowe on Instagram: @tinarororo

Oyster Shell Ghosts

I was given a box negatives that were found at a car boot sale along with other items related to photography. It seems the negatives were developed by an amateur photographer who wasn’t particularly skilled so it was difficult to gage what the actual images were. I used them as a practice as I had intended to print portraits of trans racial adoptees on these shells as I liked the literalness of printing a discarded thing on another discarded thing. These negatives seemed more suitable because the subjects really are lost, there are no names, it’s possible to guess the timescale from their clothes but even the relationships between the subjects are not fully clear. Placing the images on the shell and displaying them amongst other items mudlarked from the Thames while encouraging the audience to pick them up and examine them meant that these figures were really looked at, really seen, if only for a moment.

I studied early modern English history as an undergraduate. I became very interested in how the process of recounting history often erases the majority of the individuals who contributed towards it. We see palaces and talk of the people in whose name they were constructed instead of thinking about the people who built them. But each and every one of those people was an individual, with a name, with parents, someone who ate and drank, slept and dreamed.

I like to mudlark, which is picking up items from the shore line of the Thames in central London. A few years ago I started to notice the thousands of oyster shells that can be found near St Paul’s cathedral. Oysters have never grown in central London, they had to be bought in from Essex and Kent, along mud and gravel roads, by mule, in carts. Over 100s of years millions of them came through, were sold, shucked and consumed and the shells thrown back into the river.

Every one of those shells attests to a way of life and by association to individuals. We can piece together an outline of a human being from a shell, from an analysis of the chemical traces we can place it, examining the ridges and how far apart, how old the bivalve was and even when it grew so we can place it in a specific historical context and make guesses about the people who transported, sold and ate it. Those are the material facts of a life. Everything else is gone.

It doesn’t take long for people to become lost to us. So when my brother in law gave me a box of negatives he’d found at a car boot sale I decided to print them on to some of the shells I’d been collecting because I liked the fact these disparate objects were weighted with history that was easy to ignore unless something made people stop and look.

This work is usually shown on the floor of a gallery in and amongst other objects I have picked off the shoreline including modern garbage, grit, bones and gravel. People are encouraged to look at and touch the objects. This is counter to what you might usually expect in a gallery. People swiftly go from realising that they are looking at another human being to thinking about their own relationships. One of the most important properties of these images is that they sit easily in the palm of the hand. People hold them with great gentleness, they think about the people in the images and frequently memories of people they have known are triggered. This work won the Denis Roussel Award in 2019. -Tina Rowe

Kassandra Eller: How did your photographic journey start?

Tina Rowe: I got interested in the way things look because the way I look has always been an issue. I am an Anglo Somali transracial adoptee (TRA for short). I grew up in a white family in a white part of the UK in the 1970s. I experienced a lot of dimwitted racism in my day-to-day life, at school, in the street, even at the hands of parents of my friends. My family never experienced the grinding tedium and fear that being on the receiving end of that stupidity entails. I inhabited a different world in the same space as the people I was closest to. It felt very unfair because it was.

When I tried to address it, at home and at school, it was often dismissed as me making mountains out of a molehills. It’s quite shocking to think of that as a response to a bullied child now, but we were still in the foothills of the stiff upper lip and other forms of emotional unintelegence in those days. The positive was it made me observant because avoiding trouble made life easier. Being observant has other benefits as, although I had very little agency, one area I had complete control was drawing and I was quite good at it. I particularly liked graveyards, not least because they are pretty static, but also because people write on gravestones. There was always some kind of an outlier who told a story in more detail than the others. I’d wonder why they felt the need to depart from the usual born/married/offspring/died formula which then made me think about the lives of people who had not which kind of led me into thinking about all the other signs of lived lives around me.

My home town, Malvern, is pretty ancient. Amongst the many visitors had been Romans. Roman armies were diverse, it’s not impossible that someone who had been born in what is now Somaliland could have stood in the same places I walked around every day. Someone who’d been born in a hot, caramel colour landscape with vibrant intense blue skies could have been standing on the top of the Worcestershire Beacon looking across softly lush green hills that fade towards the Welsh Black Mountains, probably shivering.

The urge to record through drawing took me to art school. I was expecting advanced drawing lessons. But that’s wasn’t how my art school functioned and I was quickly disillusioned. They did, however, give us classes in photography which I enjoyed. Then suddenly, my father died at the age of 52. The darkroom became the only place where what had just happened was forced into the background because developing and printing is a process, especially when you are new to it. You click, wind, rewind, you tank your film: dev, stop fix, wash, you print your photo: dev stop fix, wash. Those hours of concentration in the dark meant I did not have to be in a world that had this awful crater in it. Plus I was taking the photos using my father’s Praktika Super TL, so I guess, in the darkroom, I had a way of still being with him.

I photographed walls, paths, buildings, the landscape around me. I produced no real work as per my syllabus and was rightfully booted out at the end of the year. I was a pretty pissed off and petulant teenager so I destroyed everything connected with the course except the stuff associated with photography and photography became an essential part of how I dealt with the world.

KE: How did you discover alternative process photography? What made you want to experiment with this?

TR: I tried a few darkrooms after art college, but they were full of bearded men who talked a lot about focus planes and wanted me to pose for them so I gave up. In the early 90s I spent three years in Krakow, Poland teaching English as a foreign language and took loads of photos which I paid to have developed until I found this amazing little hat shop that also sold photographic equipment. I bought an enlarger, trays and chemicals and constructed a darkroom in my bathroom. I spent most of my spare time walking around Krakow, letting my camera lead me. After I lived there I lived in Hamburg and went back to using public darkrooms.

Ultimately, I knew teaching English alone wasn’t going to pay my pension, so I decided to return to the UK. I wasn’t sure what to do and seriously considered applying to study photography, but fear of destitution made me study teaching and learning with technology and ended up with a 20 year career that was an increasingly well paid exercise mainly in being sidelined. In 2003 I was offered a job in Leeds. I still had my photo habit and part of why I took this post was I reckoned I would be able to find a public darkroom there and without the distractions of the life I had in London, which was full of distractions. I thought I could knuckle down and learn more about printing. But I couldn’t find a darkroom for love nor money, which seems bizarre now, but that was back in the day when Google’s strapline was still ‘don’t be evil’.

What I did have was a good scanner and had strong photoshop skills, so although I didn’t develop my films, I could now produce prints which could easily become negatives. I also found a book about alternative photography in the university library and I decided to have a go at gum prints and cyanotypes as no darkroom was necessary.

It was still easy to get dichromates, so I began with gum prints. I think it’s magical that you can make a print with watercolour or ink. I was very taken with Stephen Livick’s multi layered colour prints and initially tried to make similar work but I wasn’t patient or accurate enough to get the kinds of results he did. Nevertheless, the possibility of darkroomless work really appealed to me because I wanted to print.

By the time I’d come back to London in 2005, I’d made a fair number of prints, had an understanding of the possibilities of the processes and had discovered some great alt photo groups on Flickr, which were much better than the fractious alt-photo discussion groups I had been relying on. I learned more by seeing what was possible. By 2009 I had connected with Sebastian Sussman via Flickr and on facebook and he eventually persuaded me into Double Negative Darkroom for a lith printing course and it’s from there that my practice really started to come alive.

DND had a serious community of practice connected to it. There were regular courses on wet plate, carbon, mordançage and I lapped it all up. Those processes fit better into the way I wanted to create images because of the need to think about substrate, chemistry, heat and light, in ways that the darkroom for silver gelatin just didn’t. There are rules that you need to follow, but those rules are frequently bendable. By 2013 I’d met Douglas Nicolson and we built a studio above the darkroom which we still share.

KE: Is there anything or anyone who inspires you?

TR: In 2015, along with Guy Paterson, Paulene Morphett Douglas Nicolson and Ben Bradish, we took over the running of DND and changed the name to e5process. We are an artist lead darkroom and I guess we are a bit marmite, you either love us or hate us. We provide facilities for colour, black and white and alternative. We don’t provide technicians but any one of us will chat about the possibilities of this or that process, share ideas, methods and leads. I find that really inspirational.

I mentioned Steven Livick earlier because he fired my interest in gum printing, but my particular interest in liquid emulsion came from visiting Hacklebury Fine art and seeing the work of Stephen Inggs and Edward Dimsdale. I was blown away the first time I saw these two artists, I just couldn’t get my head round how it worked. As my own technique has developed, they have inspired me to think about emulsion in different ways and to consider how I might use it as an element of the final image as opposed to a layer that the image goes on. I particularly like the work of Edward Dimsdale and cannot recommend him too much.

KE: Alternative process photography allows the artist’s hand to be present in the work. For this project why did you choose this alternative process method and how does your interaction in creating the images affect the meaning of the work?

TR: As a TRA, I’ve always been asked about where I’m from and where my parents are from. But the question really is, “how come you look the way you do”. I wanted to make some work that got away from those questions about TRAs and would focus on the experience of being a TRA. I thought it might be interesting to print portraits of other TRAs on things that had been cast aside. I started off collecting shells from the tidal Thames in central London in order to make fractured portraits of other TRAs. I didn’t like the results because the images were too dislocated. By the time I’d got that far I’d discovered that the emulsion didn’t always stick to the shells, so I needed to learn about subbing. Then I realised I didn’t like the way the emulsion was pooling in some areas and not others so I started to modify it to give a much smoother coat. I also grew to really hate brush marks because they really stand out of small objects, so again, more experimentation was involved. I was down a rabbit hole and although the subject had been discarded, the process was too interesting to abandon. Then my brother in law gave me a box of negatives he’d found at a car boot sale. They just seemed like a natural fit, and they were. I guess I’m present in the idea, but I really worked hard to not be present in the process. I threw a couple in the sea at Walton on the Naze last year and they quickly appeared on a Facebook group, there were some questions about how the images had got on the shells, but they were outweighed by speculation on who the people were and how they reminded them of their own family albums, which was what I was trying to achieve.

KE: How do you handle mistakes when using alternative processes? Are there times when an error turns into a piece?

TR: Liquid emulsion is pretty fragile, it certainly fogs easily. I use Foma LE because it’s fairly cheap but you need to look after it. I’ve had two litre bottles that have been less than perfect but they’ve been a god send in some ways. I wanted to get textures into some prints and I used the fogged emulsion to do this. Foma also make a lot of the papers I like to use for lith and I was glaring at some fogged emulsion one time and the penny dropped, if I can use fogged Foma paper, I should be able to use fogged Foma emulsion. And I totally have done.

I take nothing for granted with these products and I’ll mess with them until I get bored, which hasn’t happened yet. These days I’m a pretty good record keeper. The biggest mistake I make is to not properly record my darkroom shenanigans.

KE: Each oyster shell has its own imperfections and unique shapes. How did you decide what images to use on certain shells? What was the process like when deciding on each composition?

TR: There’s no magic here. I print the same image on different shells until I get one that looks right. The more I do the more I got a feeling for what flitted where. Why some things work and some things don’t can be interesting but I don’t dwell until something flicks a switch. I trust my eye but I know that other people like different pieces more than me. I find the like counts on my Instagram really telling as a result. The stuff I think is towering genius frequently is ignored and the stuff I think is sub-par, often gets way more likes than I think it deserves. I make the work, it’s up to you what you think about what I’ve made.

KE: You discuss the idea of being lost or forgotten in your project statement and I would like to discuss the emotions you felt as you created this work. Did you feel as though by utilizing these shells and found photos you were creating a new narrative for these objects?

TR: I don’t think of this as creating new narratives, rather that I’m reminding people that the subjects have narratives. Placing an image on a substrate that offers the audience an alternative way to look at and engage with the image of another human was the purpose. It matters to me that people are listened to and looked at as individuals. Even abstracted from their lives, even if only present in a single frame, they are still images of individuals. The purpose of this work is to nudge any audience into considering that the human beings represented on the shells were just as much a complex network of relationships, ideas, physicality and life as they are. I also feel it’s important to acknowledge that the shells themselves are just as much evidence of individuals. They were collected, packed, transported, shucked, eaten and tossed into the river Thames. Each and every one of those acts is just as much evidence of a life as what is printed on them. Each shell encompasses a network of experiences. Just like our lives. Nobody is special. Nobody is not special either.

KE: To conclude I would like to ask what is next for you. Is there anything you are currently working on?

TR: I’m always doing a few things.

The work that started with the shells as blossomed into some other areas. I have a continuing project where I photograph fruit and flowers that grow in the urban landscape. They have to be things I pick and use and they have to photographed in a specific way, the film developed using particular chemistry and printed with liquid emulsion on tosa washi paper. I’ve also experimented with metal leaf on the back of the print which gives it a really lovely glow, or printing on both sides of the paper. It’s good to use the skills I learned in the shell project for a completely different set of works that still manages to explicitly map an interest to a making practice.

More important to me personally I guess, is a recent trip to Somaliland which I crowdfunded for. I gave a cyanotype workshop while I was there, which was a nothing like giving one in any of the other places I’ve done this in the past as art making really isn’t part of the local culture. I did a lot of prep work before with cyanotype on cloth and discovered a few things that have turned into new works. I’m beginning to put some kind of a response to it together. It was a challenging experience, totally different from any residencies, travel or holidays I’ve ever taken. It has broadened my understanding of ideas of home and belonging.

In terms of output, I’m still mulling it over. Most of the images I took were digital, but I want to make analogue prints, so there is going to be some decisions made about how I will present them, do I make contact prints? Do I use a copy camera and make film negatives? I’m not sure. But I intend to make a book of some kind. I make a lot of little books of my art works, but I think in this case I’d like to make something that has more than an edition of one, so maybe a publication on Issuu. The possibilities are endless.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026