Ruotong Guan: Falling. Slowly. but,

This week we are looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our last call-for-entries–way back in late-2022 (a new call will be going out sometime in the near future, so stay tuned for details…). Today we are viewing and hearing more about Falling. Slowly. but, by Routong Guan.

Ruotong Guan, born in Hefei, China (1998) is a Shanghai-based visual artist. Her photography explores female identity and family dynamics including familial relationships, shared spaces and ideas of home.

Guan received her BFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2021 with the Merit Scholarship. Her work has been exhibited at Three Shadows Photography Art Centre (Xiamen, China), Czong Institute for Contemporary Art (Gyeonggi-do, Korea), Mana Contemporary (Chicago, IL), and Site Gallery (Chicago, IL).

Follow Ruotong on Instagram: @weveebeen

Falling. Slowly. but,

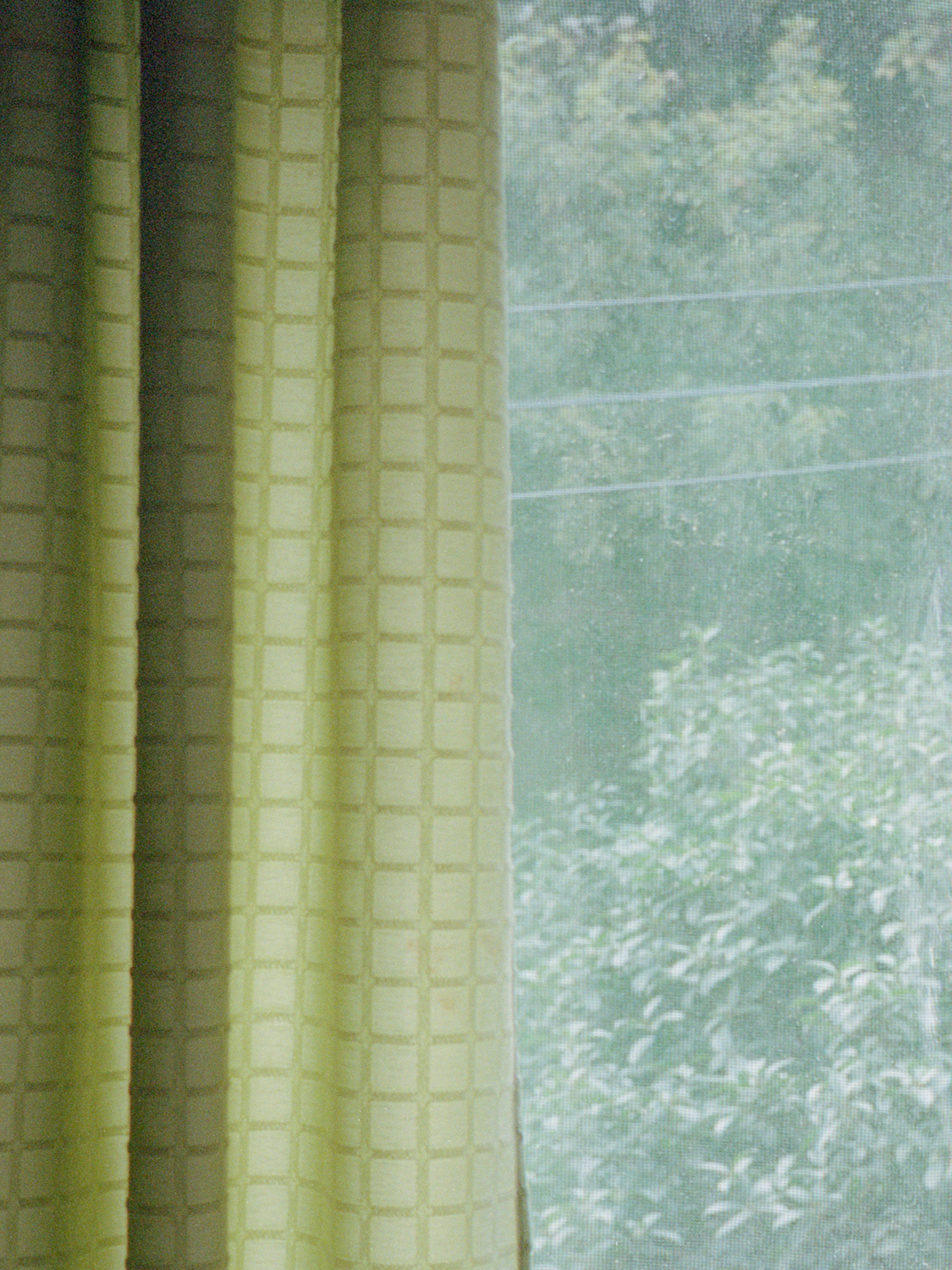

My photography practice explores family dynamics and female identity. I photograph my family, the imperfect worn-out domestic objects, and the physical space my family shares.

When making projects, I draw inspiration from family memories, looking back on the past and contemplating what brings not only me but us to where we are today. With photography, I seek to convey the nuanced complexity of both familial relationships and societal dynamics while visualizing my gentle intangible emotions. I see the pains and the happiness around my family, I notice their aging while I grow, and I know what we are struggling for. I make photographs to make me remember, to walk from the past to the future.

Daniel George: What motivated you to begin Falling. Slowly. but,?

Ruotong Guan: It was back in early 2021, when I came back home from Chicago during the pandemic. On the night of Chinese New Year, we had dinner as a family, my grandfather told me that the house where he and my grandmother live was added to the government demolition list and that he had signed the paper declaring his agreement to the action. He was told that because of the dilapidation, there could be safety issues and that it was no longer fit to live in.

I was the last one in the family to know this because I was away for a long time. It caught me off guard as it is an important house to me and my family. My grandparents have been living in that house for more than three decades. Both my uncle and my mother lived there before they had their own family. My cousin and I shared a great childhood there with our grandparents. I still remember the summer days when I would wear a silk dress my grandmother made for me, and play in the backyard.

Since the demolition would only take action if more than 92% of the people who live in that area sign the agreement, no one knows when it will happen or if it is really going to.

The possibility of losing the house, the urgency, and the frustration make me keep going back to my grandparents’ house, to stay with them, and stay in the house.

It is the reason why I started this project.

DG: You write that you are inspired by “family memories, looking back on the past and contemplating what brings not only me but us to where we are today.” Would you elaborate on these interests?

RG: When I was making this project, I spent a lot of time with my grandparents. My grandmother has been diagnosed with diabetes ever since she was young. Her memories are clouded by the side effects of the disease and her aging. She remembers things from many years ago in detail but barely anything happened in recent years. So when I was in the house with her, she kept telling me about those old-time stories. I learned about my grandparents’ migration from Shanghai to Hefei in 1969 which later became the relocation of the whole family; my mother’s younger days before she took on the identity of a wife and mother; the inevitable family fights; and of course, my childhood anecdotes that I have no memories at all.

These family stories make me realize that there are more similarities we share in our blood than I thought. They all shed a shadow on me, more or less. The most amazing thing for me in this process is that I get to learn about my mother from her mother. It is a completely new perspective and actually leads me to my other project “Like Mother, Like Daughter”, in which I especially focus on mother-daughter relationships, and women’s identity outside of the family.

DG: As you made the photographs for this series, did you gain any new insights into your family dynamics, as well as your own identity? Would you mind sharing?

RG: Yes as I mentioned above, my grandparents relocated from Shanghai to Hefei, taking my mother and her brother with them. This relocation isn’t just about places, but also language. The entire family of my mother’s side speaks the Shanghai dialect, which has a completely different system and pronunciation from Mandarin. My father speaks Mandarin, so does my mother when she speaks to him. Shanghai dialect is a secret channel for my mother’s maiden family only.

I grew up speaking Mandarin and listening to the Shanghai dialect. The communication between my grandparents and I was not always smooth, not to mention that my grandmother could barely hear anything unless it was yelling because of the side effects of diabetes. It was kind of weird when my grandfather and I talked in Mandarin, and he would translate some important information into Shanghai dialect and yell it out to my grandmother. It was a very visualized and presented language barrier inside of my family, and I stood right in between.

My grandmother always wants me to claim myself as a Shanghainese, as Shanghai is a more advanced and developed city. Ironically, I even couldn’t yell out in Shanghai dialect to her myself.

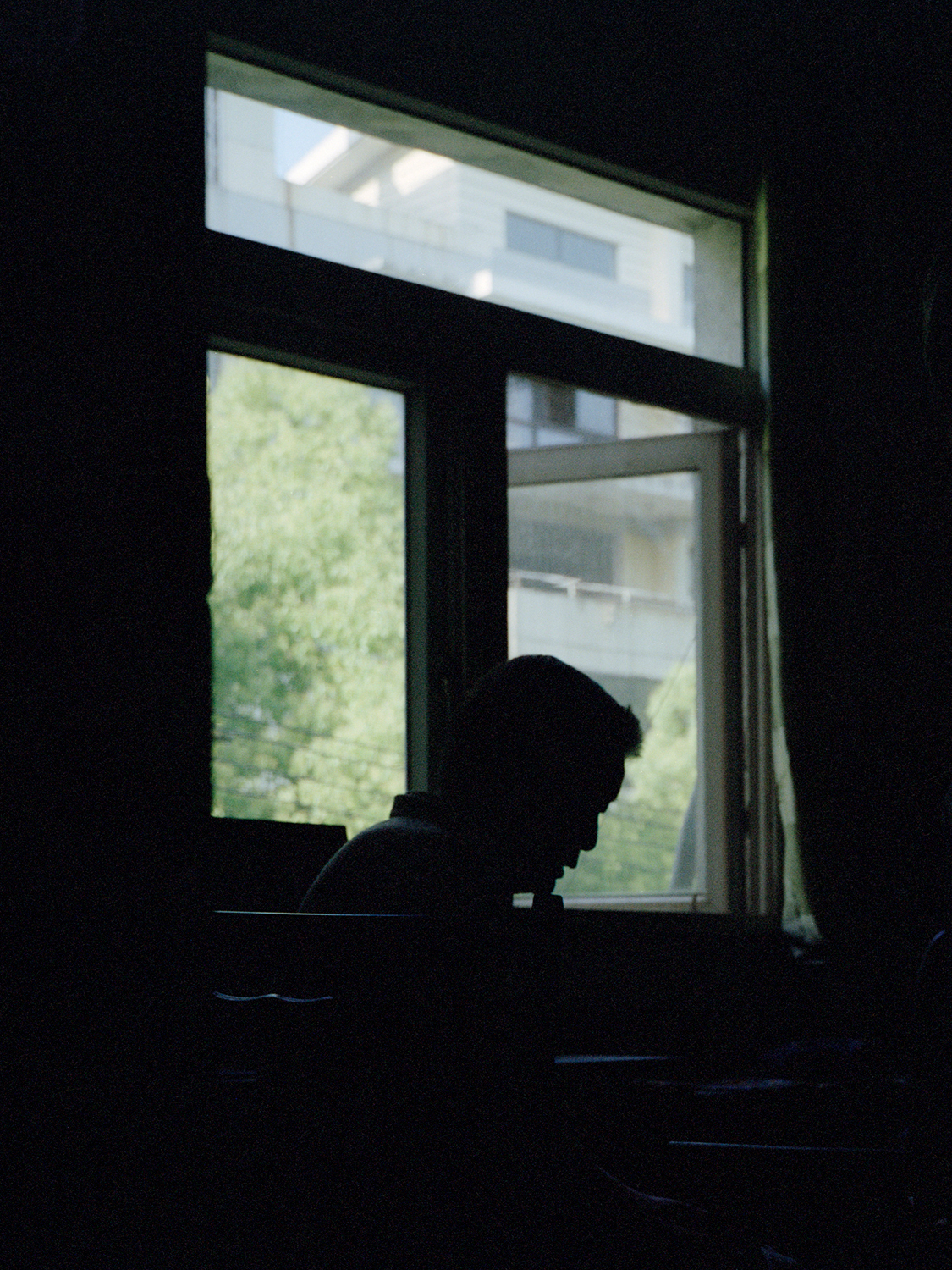

My in-between position gives me an excuse to be the observer and listener in the family, granting me the freedom to look around and photograph while they talk.

DG: I was drawn to your use of domestic objects and physical spaces, along with photographs of your family, as a means of describing your familial narrative. What significance do you see in contrasting these types of images?

RG: From my perspective, domestic objects, physical space, and people – these three bring together the idea of home and family. Take the clock in the image “A Crack of Time” as an example. Time is especially important to my grandmother as she has to take her injections and medicine strictly 30 minutes before the meal. That clock has been on that bedside table forever. The crack, the rust, the medicine and the cotton swab used after the injection reveal the importance of time, the health condition of the person in that space, and a subtle stillness.

Every home has a distinct smell. It comes from the food this family cooks, the shampoo they use, the plants they keep… It is the witness of the day-to-day life that happens in that physical space. My images are the visuals of this distinct smell. They present a life and a characteristic in front of the audience.

DG: What do you feel photography contributes to your practice of communicating the “nuanced complexity of both familial relationships and societal dynamics.” What more are these images able to say?

RG: Photography brings focus and attention. It urges me to be more aware of my being and surroundings. And what’s interesting is that when I hold a camera, it is an identity switch – my family sees me as a “professional photographer”, a grown-up, other than their daughter or granddaughter. They would have a real conversation with you, instead of asking what you want for dinner. This identity switch helps me take a step back to look at my family in the context of Chinese history and social changes.

I spent five years in America, which changed a great deal of my ideas on relationships. It is a stereotype that we Asians tend to be more implicit in expressing their feelings. The most common example is that we don’t say “I love you” as frequently as the Westerns. For the older generations, perhaps they would only say it on special occasions like weddings. I realized that I should say it more often so I practiced, but the most of time my family didn’t know how to react and considered it awkward. Therefore I spend more time with them and take photographs with affection, the implicit Asian way. I hope that my images may reflect some characteristics of Asian families that are not well presented or understood and say “I love you.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026