Once-Taboo: Tynan Byrne’s Polaroids of Bonding and Brotherhood

This week on Lenscratch we present an eclectic survey of photo-based artists exploring issues of Queer identity and representation. These exceptional artists expand our appreciation for diverse photographic techniques, directing our attention to critical issues of bodily autonomy, reclamation, and belonging.

Today, our focus is on Massachusetts-based photographer Tynan Byrne. A Q&A with the artist follows.

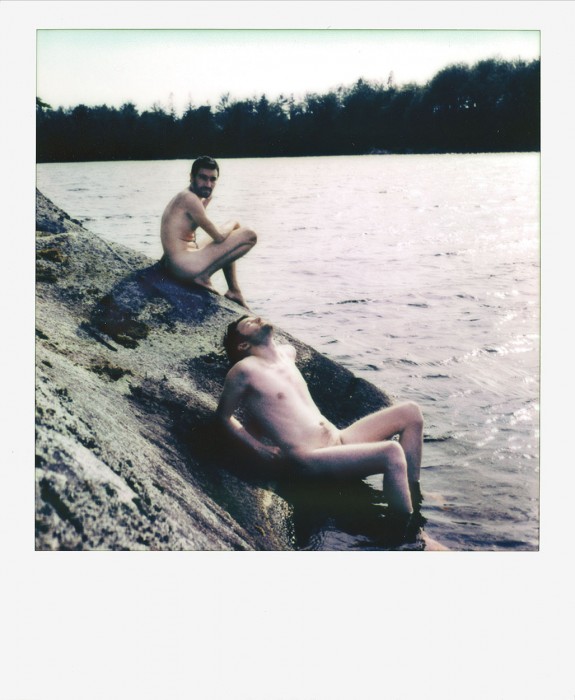

Tynan Byrne is a photographer in Somerville, MA. His series center around intimate and honest aspects of his life as a gay man–harkening back to childhood in Maine, his interpersonal relationships, literature, and love for the history and methodologies of photography itself. The work in his current series challenges the notion that male nudity is too often reserved for and confined to sexual settings; that when gay men occupy such an intimate space with straight men it is done so as an act of exploitation. His photographs exemplify fraternity evolving, quelling dormant anxieties of unworthiness and disavowing fears of inequality.

Most recently, he has had work exhibited in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Montgomery, Alabama, Dallas, Texas, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, as well as several online galleries and publications. He received his first solo exhibition at Gallery Kayafas in Boston, Massachusetts which ran in the Spring of 2022, and has a second solo show slated to open in the summer of 2024 at Gravedigger’s Daughter Gallery in Maine. Byrne is part of the artist critique group Recently, and is currently working to create a new artist collective in the Boston area of gay and queer artists, creating a space for its members to share their work amongst like minds and seek out opportunities for exhibition, publication, and discourse. He currently works as the Instructional Media Technologist within the Art Department at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.”

Follow Tynan on Instagram: @tybyphoto

Polaroids

My developing body of photographs seeks to magnify the unconditional—if at times inscrutable—friendships with straight men whom I’ve grown up alongside. Drawing on the ways that Polaroids, particularly as singular objects, have impacted gay history—as keepsakes for gay men to cherish once-taboo intimacies, or to be displayed in bathhouses and gay bars as rights of passage—I opt for the uncompromising lens of a Polaroid camera to retain the fleeting, charged moments during casual exposure to prioritize fraternal camaraderie. This ongoing project ties this secret history to the present—part research, part performance—to create a modern iteration of men admired and rendered on film.

The series depicts the private battles between Affection and Admiration that I inherently waged throughout my adolescence and early adulthood, when discerning where lust diverges from those of fraternal love was often a challenge. By capturing our spaces of shared vulnerability, where the subject and I are both nude, I reference an early tenet of the gay community when men relied on Polaroids to preserve their lovers and friends without fear of repercussions or being outed. The taboo of gazing at the male form in societal and art historical contexts had taught me to fear that which I was inherently drawn to and desired, in turn creating a compounded disconnect between myself and my gay identity. In facilitating scenarios in which my subjects and I share a vulnerability, I have equalized our dynamics while still maintaining control as the photographer.

These documents of fondness are indulgent and fraught; they push the boundaries of these friendships yet are still capable of bridging the distance between male-to-male relationships. In the way of past era’s Polaroids have in turn become a secret history, the work in this series is my own private keepsake—talismans of power regained and recontextualized.

Why was the Polaroid your medium of choice to explore ideas revolving around sexual identity and expression?

Initially, it wasn’t. The Polaroid for me was always a more casual, lackadaisical method of documenting my life. I saved what I deemed as my, “real work”, to my other cameras like the Pentax 67 or the Hasselblad. Polaroids were always a part of my home life with my friends and my partner throughout our changing apartments, ways to archive who came over, the parties we’d throw, the silly gay events we’d find ourselves in, etc. So it wasn’t until I looked back and examined many of these shots that I considered there being something work following in the nature of these images. I had, up until this point, been working on a project in which I photographed my friends nude in domestic and outdoor situations, but I found they were so rigid, so formal, and lacking an element of whimsy—moving to the Polaroid would allow a bit more fun to be had. Shooting with an SX-70, SLR 680, Now+, or Fujifilm Instax Square, meant I could pocket any of these cameras and go anywhere, uncollapse them or whip them out and make quick, painterly shots, while getting an image in a matter of minutes to show my models just what it was I was eager to capture. It welcomes collaboration, and an immediate bonding point, deepening the relationships between maker and subject while fawning over the excitement of a physical photograph to hold and watch change right before our eyes.

The Polaroid also, as we know, is so beautifully prone to error in the most exciting way possible. An uneven spreading of the chemistry through the roller can produce strange color shifts or kiss marks, and sometimes an image just comes out strangely. The shutter happens to get stuck open, the metered exposure is too dark, the model had just fallen out of frame, or the camera spits out two shots at once, and then you’re left with one less frame to work with. But in that chance of loss comes opportunity, and it can be thrilling to work around, especially when you’re photographing something as live as a performance of nude expression. The livewire nature of the medium offers the same air of nuance and nervousness as the process of examining oneself in the presence of others—what you hope for may not be what you get, no matter how exacted and premeditated the image in your head may be.

What are your considerations when working with the male nude in your practice?

There’s something neutralizing about being nude—it recalls a kind of starting point every time you exist fully exposed in a space with another. Initially, the models I chose for my work were close friends of mine; straight men I had grown up with in high school and who are still dear to me. They were people I trusted and who trusted me, people with whom I shared a history and who I wanted to show respect and love for in my work. To achieve this, I use nudity as a mode to equalize our power dynamic, when at earlier points in my life I had felt inherently inferior to these straight men during my adolescence, I now wielded the opportunity to rewrite that self-imposed law which kept us emotionally alienated. As the photographer and facilitator, I ensured we acclimate to this new boundary, one I’d pushed our friendships into, before beginning the process of making images. We would casually lounge, address our own or each other’s bodies or simply carry conversations as though nothing was different, at which point the shoot would begin, waiting for casual gestures to present themselves or moments to pass that would spark an idea.

This process grew beyond just photographing those I’d grown up with, and has moved more into inviting others I’d grown close to to partake in the project—other straight friends I’d made as an adult, and eventually evolving towards photographing other gay and queer friends. Each shoot pushed the extent of our friendships to new levels, and created space for us to revel in our own nudity, performing a kind of pride and basking in the strangeness our bodies naturally possess. I would think of the works of past Polaroid artists, consider what circumstances they’d found themselves in to have captured their models, how they were likely rarely platonic acts but rather steeped in secrecy, taboo, and anticipation. How did this differ or relate to my work? When I look at my work, or the works of other queer photographers utilizing the Polaroid, I bring these considerations to the work, and how the photographic object is so bound to a history which seems to only be understood peripherally, inherent to the nature of using a machine to create a single document with little to no footprint. There is, for me, an entire undiscovered world of the male nude hidden within boxes and attics or destroyed over time; an Atlantis lost to time holding a culture now more widely acknowledged, accepted, and lauded for making personal work. So to contribute to the evolving mythos of this contemporary history in something as simple as a Polaroid is not only tongue-in-cheek and exciting, but also an honor.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026