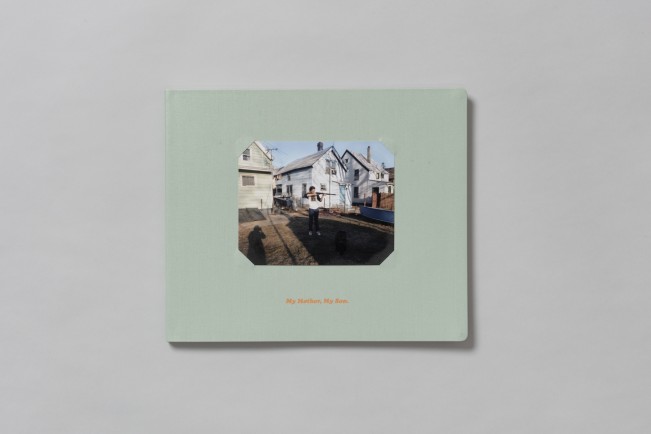

Mary Frey : My Mother, My Son.

Mary Frey is a master at finding the drama in the familiar and her most recent publication, My Mother, My Son., published by TBW Books, is a potent distillation of what she does best. A selection of both B&W and color photographs depict everyday people in everyday moments that, to me, feel like invitations into someone else’s memory. With a tipped-in print on its cover, My Mother, My Son. echoes a family album in which Frey challenges us to reflect on memory and the transient narratives of our lives.

I met Mary when I was a grad student at the Hartford Art School. She had already retired from teaching full time but had returned to review our thesis projects. As a fan of her work I was delighted to meet a hero and watch her gently deliver insights that cut right to the heart of our fledgling projects. And now, I am happy to continue a conversation, this time about her work. Our talk ventures beyond photography and into the functions of memory as well as the surprising ways we can learn about ourselves through the act of making.

The following is a transcript of a conversation between Tracy L Chandler and Mary Frey.

TLC: Can you share the backstory of My Mother, My Son. After the first two images (one of your mother and then your son, correct?), we are then introduced to a slew of characters, some repeating, others not. Are these all photographs of your own family and friends?

MF: Incorrect! The only image containing my mother and my son is the last one in the book, which was made during the final weeks of my mother’s life. All the other photographs are a mix of family members, friends or people I met while photographing in various places over a period of ten years. I often developed a relationship with these people and returned to photograph their activities again and again. And, yes, I consider them my cast of characters in my ongoing saga of living a life.

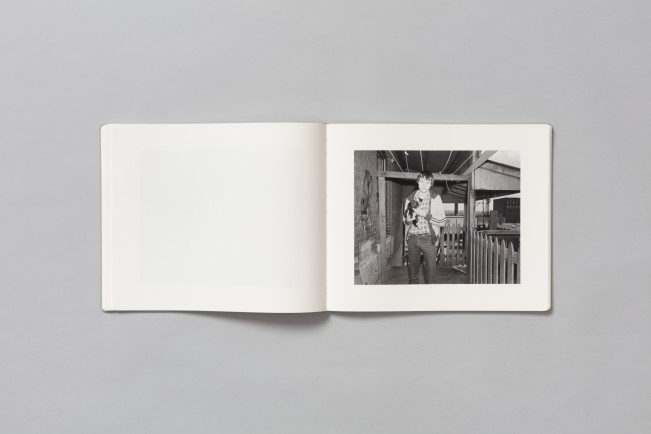

In 2017 I delved into my archive of images in order to create a book from my earliest black & white work. I titled it Reading Raymond Carver. A year later I produced a book with color photographs from my series Real Life Dramas. In thinking about these two books, I realized that the first asks questions about what choices we make while living our lives, while the second one embraces and celebrates those choices. My Mother, My Son. plays with the elusive idea of memory, considering where we have been and what we know, while contemplating what is indeed beyond our vision. It feels like a bookend to these first two publications.

TLC: Thank you for correcting me! I love that I got that wrong. It points to the subjectivity of photographs and the projecting we do. I wanted those first two images to be your mother, your son. The title set me up for that and I wanted to close the loop!

This book does feel like a progression of your previous books. Photographs are the perfect medium for contending with the elusivity of memory… what we think we remember, versus what we see in the image. One replacing the other, until they both lose any real mooring. Had it been a long time since you looked at these images? Were there any surprises?

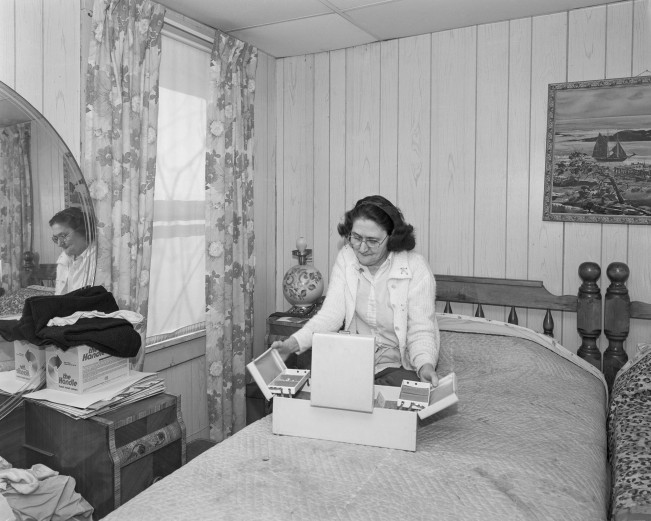

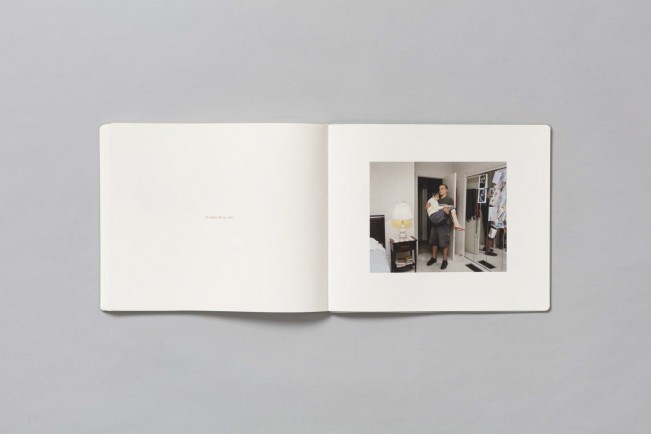

MF: For this project I dug into my contact sheets as far back as 1978 and reviewed work up until 2004—the date the photograph titled My Mother, My Son was made. I wanted to build the book around the feelings suggested by this image, so my challenge was to create a narrative arc that carries a viewer through different scenarios that describe the joy of looking balanced with a sense of self-reflection. There were some images I had never seen or forgotten about (surprises, for sure), as well as some that my mind stubbornly kept returning to. Nonetheless, I was really able to look at all this work with fresh eyes. Since a photograph holds its own fiction, its meaning may slip, shift or change depending upon the context in which it is placed. I decided early on that the first photograph—the woman looking into her jewelry box, like peering down a rabbit hole—should begin this journey.

TLC: It begins the journey so well! The way she is opening it too, like a book. I love thinking of this image as a metaphor… the book becomes a box of photographic treasures!

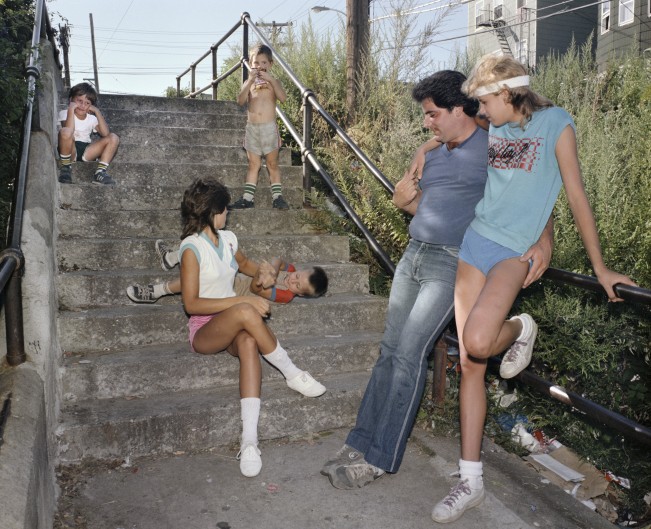

In this work you mix color and black & white photographs together. How do you see them playing on memory and fiction differently? Do we “believe” one more than the other?

MF: When I first began to put this book together I had two goals. The first was to use the photograph of my mother and my son as a way to provoke a conversation around aging and memory and the second was to see what would happen if I combined my B&W and color images together. It took me a while to reconcile their combination and in the end there are—excluding the cover print and the last image—only 10 color images within an edit of 21 B&W images. It’s not a matter of “believing” one form more than the other. I feel the B&W images operate in an interior space, a place of remembering in the broadest sense, whereas color can suggest so many readings—visual, sensual, emotional, referential, historical, etc. In the sequence of the images I see my color photographs acting as interruptions that bring the viewer back to a moment embedded in a reality—even if that reality is only located between the four edges of the frame.

TLC: Yes! You describe it well. It is less about believing and more about shifting between states of awareness… “remembering” is another way of being fully embodied in a moment, that moment just happens to be the past. The B&W images do tilt us toward that kind of presence whereas the color images are more akin to how we see and experience the present. But either way, we are still looking at photographs. Like you said, between the four edges.

I have to say though, your photographs really draw me into the content. I forget that I am looking at a picture and I jump into the story, the drama of these people and their lives. They are in the midst of the most everyday living and here we are right along with them. Even with flash, even with a posing subject, you still have a way of creating a casual intimacy that helps the viewer drop the stance of the observer and just go right in. I am wondering about your process, your way of accessing these subjects and photographing that allows for this… How do you choose your subjects? Do you spend a lot of time with people before photographing them? Are you participating in the same activities or just observing? What does a Mary Frey shooting session look like?

MF: My working process varies, depending upon the situation. For some of my “characters” I have specific ideas about what I want from them–for example, the boy holding his puppet–but generally I hang out with my subjects, observe their activities and either get lucky enough to release the shutter at the right moment, or in most cases have them repeat their actions. My choice of a subject is essentially visual and I’m very clear as to why I ask someone to pose for me. ( “I love how your dog looks… I love your blond hair…”) I’m strictly an observer, the fly on the wall. Not everyone works out, but when they do it’s magic.

In my early B&W work I strove to have my photographs hover somewhere between feeling documentary and staged. Given that I was using a large format camera and my subjects needed to hold a pose, this came about somewhat naturally. This way of working carried through with the color work, as well. And I generally felt my photographs were most successful when I invaded a personal, intimate space–be that indoors or out. This still is the case.

TLC: You use the word “invade” when speaking about photographing in a personal space but these photographs don’t have an aggressive quality. The way I see them, there is much love. Or, at least, respect and appreciation. You have been making these photographs for a long time. Do you remember what motivated you to go out and photograph in the first place? Does that still hold true for you?

MF: Invade may be too forceful a word, so let’s say enter. When I go out to make photographs I strive to enter spaces, either physical or nonphysical, that feel private. It’s here where a subject’s vulnerability is exposed and interesting photographs can happen. In the early years I set up a challenge for myself, to make provocative work out of my every day, never needing to travel far from home. To that end, I made up lists of possible scenarios or activities to pursue. After a while this just came natural to me while I photographed, as I began to notice gestures or moments that held meaning far beyond their purpose. That’s what got me to pick up a camera in the first place, and that’s what propels me still.

TLC: So I just went through the book again and now I see the title caption on the opposite page of the ending image of your mother and son. I had missed that on my first viewing. Sorry about that. But, wow, that picture! It is so real and sweet and heartbreaking.

MF: I made it in 2004. Despite the fact that I often photograph my family and friends in my work, I have always regarded them as simply subjects… stand-ins for ideas about family, not my specific family. This photograph is different and it has taken me 20 years to realize it’s my first self-portrait of sorts or at least a documentary moment. Thus, the urge to give it a title. I still believe that photographs hold their own truths, but I have to admit that My Mother, My Son has called my bluff.

The following is a quote by Jorge Luis Borges that has always resonated with me… I probably should have included it in the book but oh well…

A man sets himself a task of portraying the world. Through the years he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and people. Shortly before his death, he discovers that that patient labyrinth of lines traces the image of his face.

My Mother, My Son. by Mary Frey is published by TBW Books. The photobook is available for purchase through TBW Book’s website.

Mary Frey is a photographer who currently lives and works in western Massachusetts. The artist earned her MFA from the Yale University School of Art in 1979 and subsequently taught photography at the Hartford Art School, retiring from the undergraduate program in the Spring of 2015.

Frey has received numerous awards for her work, most notably a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1984 and two photography fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1980 and 1992. She was the recipient of a Te Foundation Fellowship in 2004 and an artist’s grant from the John Anson Kittredge Fund in 2010. During the 1994-95 academic year Mary Frey was the Harnish Visiting Artist at Smith College, Northampton, MA and in the spring of 2001 she completed an artist’s residency at the Burren College of Art, County Clare, Ireland.

Her work has been exhibited extensively and is part of many public and private collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Chicago Art Institute and the International Polaroid Collection.

Much of Frey’s work addresses the nature of the documentary image in contemporary culture and most recently she has worked with 19th century photographic processes to produce ambrotypes and lithophanes. She has two books of her early images, Reading Raymond Carver and Real lIfe Dramas both published by Peperoni Books.

TBW Books is an independent photography book publishing company founded in Oakland in 2006 by Paul Schiek. In 2023, TBW Books began its sister company Workshop de Allende in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

Follow TBW Books on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Matthew Finley: An Impossibly Normal LifeFebruary 22nd, 2026

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026