Semaj Campbell: Five Sixty Four

Lenscratch recently held its annual(-ish) call-for-projects, and the response was impressive. In total, there were over 500 submissions. We are eager to look through each of these entries and share some highlights over the months to come. Today I am in conversation with Semaj Campbell about his project Five Sixty Four.

Semaj Campbell, originally from Brooklyn, NY, completed his studies at Trinity College with a dual focus on psychology and studio art in 2018. Having graduated, he furthered his artistic journey by earning an MFA from Lesley University. Concurrently, Semaj serves as an educator and football coach at Avon Old Farms School in CT. Inspired by the works of Gordon Parks, Deanna Lawson, Latoya Ruby Frazier, Chi Modu, and Bruce Gilden, Semaj’s art is a testament to the reimagining of the black gaze through his personal narrative. His photography challenges historical prejudices and false narratives that have marginalized black figures throughout history. By amplifying the voices of the oppressed, Semaj provides a platform for those discarded by society, fostering a powerful counterpoint to ingrained biases.

Instagram: @semaj.doc

Five Sixty Four

My photographs delve into the deconstruction of the linear narrative and the monolith of Black life—narratives that have long been misrepresented, exploited, and confined to narrow confines. Through my work, I aim to amplify the voices of everyday individuals who have been oppressed and marginalized, often pushed to the periphery of society’s consciousness.

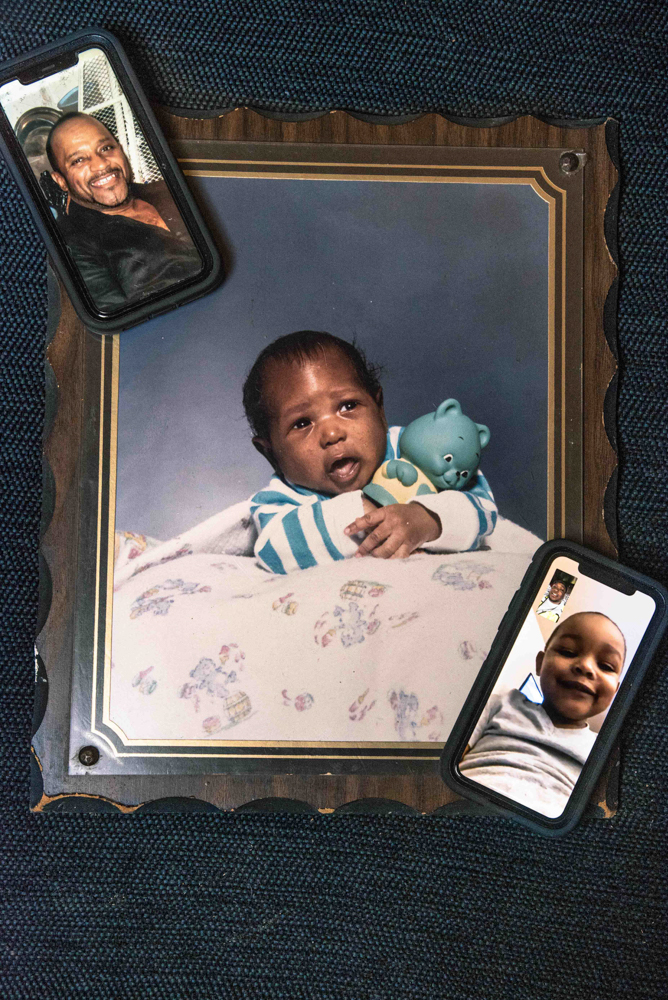

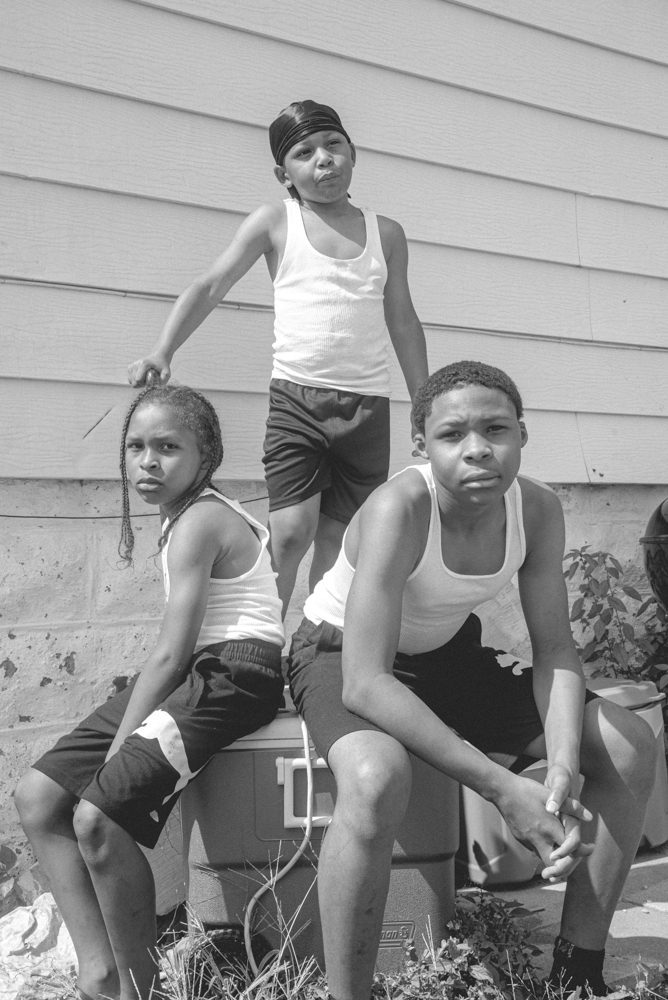

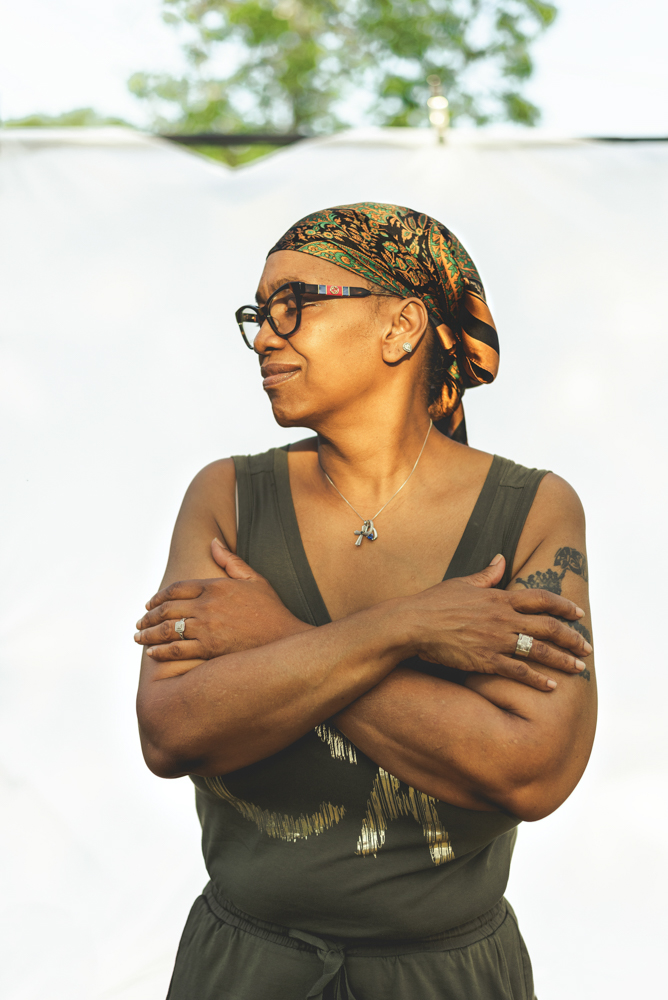

In this body of work, I turn my lens inward, documenting my own family and exploring the intricate dynamics within Black families, where unspoken and unaddressed traumas seem to persist across generations. By focusing on my family, I seek to use them as a microcosm for Black families grappling with the legacy of generational curses and traumas. My art seeks not only to reveal these complexities but also to challenge and expand the narrative of Black life, offering a more nuanced and authentic representation.

Daniel George: In your statement you wrote that your work was informed by Latoya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family. What was it about that series, specifically, that motivated you to look inwardly at your own family, and how did you translate this and make it your own?

Semaj Campbell: What Latoya did with the camera helped me understand how to involve family in the artistic process in a raw,authentic way. She showed that you can sincerely represent your truth without exploiting anyone. She did this by providing context, including a collaborative piece where her family was engaged and involved. She also addressed social issues that affected not only her family but also her community and loved ones.

In my project, I use the spaces within my loved ones’ households to create that sense of authenticity, ultimately hoping to contribute to a genuine yet beautiful embrace of one’s story and journey. Latoya’s series of images resonateddeeply with me, helping me see glimpses of myself and my family within the confines of her frames.

DG: Your work makes me think of how we are influenced by our familial relationships, both past and present. As an outsider looking in (and only privy to certain information as described in your pictures), I’m curious about how you feel these images describe your “development as a man, a black man, an artist, a black artist, a teacher, a black teacher, and a human.”

SC: I feel like everyone I’ve photographed—and plan to photograph—has had a significant impact on my life. Ofcourse, there are some family members I’ve spent more time with growing up, but I’m grateful for the unique influence each of them has had on me. My family, like any other, has its own personal challenges, yet I’ve learned so many beautiful things that have ultimately shaped me into the man I am today.

Starting with my closest family, my mom and my brother, they have been my heart, my foundation, and my support system in everything I do or set out to do. My mom is the most loving and selfless mother anyone could ask for, yet she’s also tough as nails—even though she’s just pushing five feet tall! Haha. She has taught me to believe in myself,to prioritize God and family, to incorporate discipline and integrity into everything I do, and ultimately to care for and be selfless toward others.

People like my cousins have been more like big brothers, guiding me through their words and actions. They’ve shapedmy sense of humor and deepened my appreciation for family and life. They also helped me grow as an athlete when I was younger, taking me to the park with them and letting me watch them play ball. It’s surreal sometimes to see them now as parents, nurturing their own families. Their essence remains the same, but they’ve grown into these mature, responsible figures.

My aunts and uncles were influential in similar ways. Since my mom had me at a young age, they were more like oldersiblings when I was growing up. They would let me do things my mom wouldn’t allow when they babysat me, and I remember those times as always being fun—especially growing up in New York.

My grandmother and great-grandmother were the matriarchs of the family. My great-grandmother was a little stricter, but my cousins and I always had fun at her house, which inspired the title of my project, 564. The roots of 564 begin with my great-grandmother and her husband, as I explain in the project statementand write-up. My grandmother, on the other hand, is known for her beautiful smile—I like to think that’s where I gotmine from haha. Like me, she’s laid-back and quiet but has an extroverted, fun side as well.

I could go on and on about various family members, but each life experience has molded me into the person you see today: a teacher, a coach, an artist. Much of my development as an artist, I think, stems from naturally being an introvert. Even as a child, I was always observing, noticing specific details and interactions around me. I’m still not a man of many words, but I’ve grown to be more vocal over time. The camera has become an essential tool for me,helping me express ideas and navigate my thoughts more clearly.

DG: I was drawn to the way that you use the home as both a framework around which you build a personal narrative while making connections with others in communities that are “largely comprised of black and Hispanic families.” Would you elaborate on why you feel it was important that Five Sixty Four functions as a “microcosm for the larger scope” of other people’s experiences?

SC: One piece of the project I think is crucial for people to experience is the actual voices and recordings of my subjects. I believe the photos speak a unique language on their own, but to truly experience the project in its entirety, I think the voices need to be heard. I’m currently working on a way to make that happen, but in the meantime, I do havea video on my YouTube page that incorporates the images from the project along with the interviews.

To answer your question, it goes back to what I mentioned about Latoya, Ruby, Frasier, and her project—not being only about her family, but her community. It really sets a platform for conversations about how the work transcends into other communities and households in different forms. The project illustrates something I believe many Black and Brown families can relate to, in some shape or form. Maybe it’s an image that reminds them of how their mother usedto organize her kitchen, or the way clothes were stacked on the couch during laundry day, or maybe it’s someone who reminds them of their cousin or the emotional connection they feel when they look into the subject’s gaze in the photograph.

I’m hoping my work can transcend and inspire others to create, just like Latoya’s notion of family did for me. And even outside of Black and Brown families, I believe this work can be viewed through a lens that allows it to live beyond the realm of Black art. People may have different levels of connection to the work, but I think even some White families can relate to themes of struggle, beauty, perseverance, broken bonds, loss of a loved one, and generational curses.

Many of the issues I’ve witnessed within my own family structure are similar to what my close friends have experienced,and they are going through the same things I’m going through. For me, using my camera as a tool to express and address subjects like this can help inspire someone, or at least allow someone to connect to the work in their own personal way.

DG: Your interviews with family members are a critical part of this work. How do these conversations inform your photographs, or your ways of seeing and addressing the “lingering effects” of their experiences?

SC: The interviews are really interesting. When I first started, I wasn’t sure how I would navigate them. I didn’t want the focus to be solely on trauma or negative occurrences in someone’s life. Instead, I knew I wanted to use the interviews as a platform for each person to express themselves without interruption. I also saw the interview as auseful tool to help put my subjects at ease with the idea of being photographed. Of course, all of my subjects trust me, but there’s always this element of nervousness when a camera is brought into a space. Being photographed can be nerve-racking for anyone.

In some shape or form, I think everyone wants their voice to be heard. By allowing my subjects to “talk their talk,” as some would say, I find it helps to lower their guard, contributing to a more relaxed, authentic, and fun experience. So, in one way, the interviews help my subjects feel more at ease, but they also generate ideas for how I might want tophotograph them within their environment.

Ultimately, my goal is to find the balance between sincere and dignified representation. Of course, I want photos that convey a sense of rawness, but as a photographer, I never want to exploit someone just to get a good shot. I usually have a few ideas in mind for how I want my subjects to be photographed, but then I let the process unfold naturally,working through a sense of feeling. The same usually happens with the interview questions. I might go into the interview with a few questions—some that I’ve always wanted to ask or was unsure about growing up, along with some generic questions to get the conversation started. But I often find myself disregarding most of the questions I’ve written down because the conversation takes on its own natural flow, and that’s when the best dialogue happens.

DG: In your biography you write that your photography seeks to challenge “historical prejudices and false narratives that have marginalized black figures throughout history.” How would you say that this series lends itself to this objective?

SC: I believe this project lends itself to challenging historical prejudices and false narratives that have marginalized Black figures throughout history. It establishes a platform where people can hear directly from individuals within thecommunity. Throughout history, Black people have been labeled as lazy, incompetent, ignorant, and more. Many of these judgments are based solely on what has beenportrayed in the media. What is often overlooked is how Black and Brown people have been neglected, discarded, andabused for generations, and how these injustices continue to impact communities to this day.

Is this project going to provide a solution to all the problems within Black and Brown communities? No. That’s not myintent. As I mentioned before, this is a project that I hope will inspire others, serve as something for people to connect to in their own unique way, and ultimately open up conversations and dialogue around certain issues.

I’ll close with this: One thing that has stuck with me, said by a professor in my MFA program, is the suggestion to use the phrase “a sincere representation” rather than “truth.” For me, I’ve come to realize that even with the due diligence of interviewing and photographing my subjects with integrity, it can never be the entire “truth.” It can only be my sincererepresentation of all the things I have collected and processed. I invite others to challenge, question, and disagree with the work, because that’s what art is supposed to do.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026