Christine Lorenz: Dissolution

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Dissolution by Christine Lorenz.

Christine Lorenz earned her MFA at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and BA at Ohio State University. Her photographs have been seen at photo-eye gallery in Santa Fe, in Pittsburgh galleries, and elsewhere across the United States and Europe. Online, her work has been featured by Vice, Photolucida, Humble Arts Foundation, Magenta Foundation, and Rogue Agent Journal. She was selected for participation in Review Santa Fe in 2021. She lives with her family in Pittsburgh, PA, where she teaches the history of photography and art writing at Duquesne University and Point Park University.

Dissolution

I use macro photography as a way to cultivate connections with the nonhuman world. I’ve always taken an interest in things overlooked, disposable or forgotten. Materials like salt and single use plastics, which are so familiar that we barely notice them, can become entrance points to a much bigger picture of the world and how we fit into it.

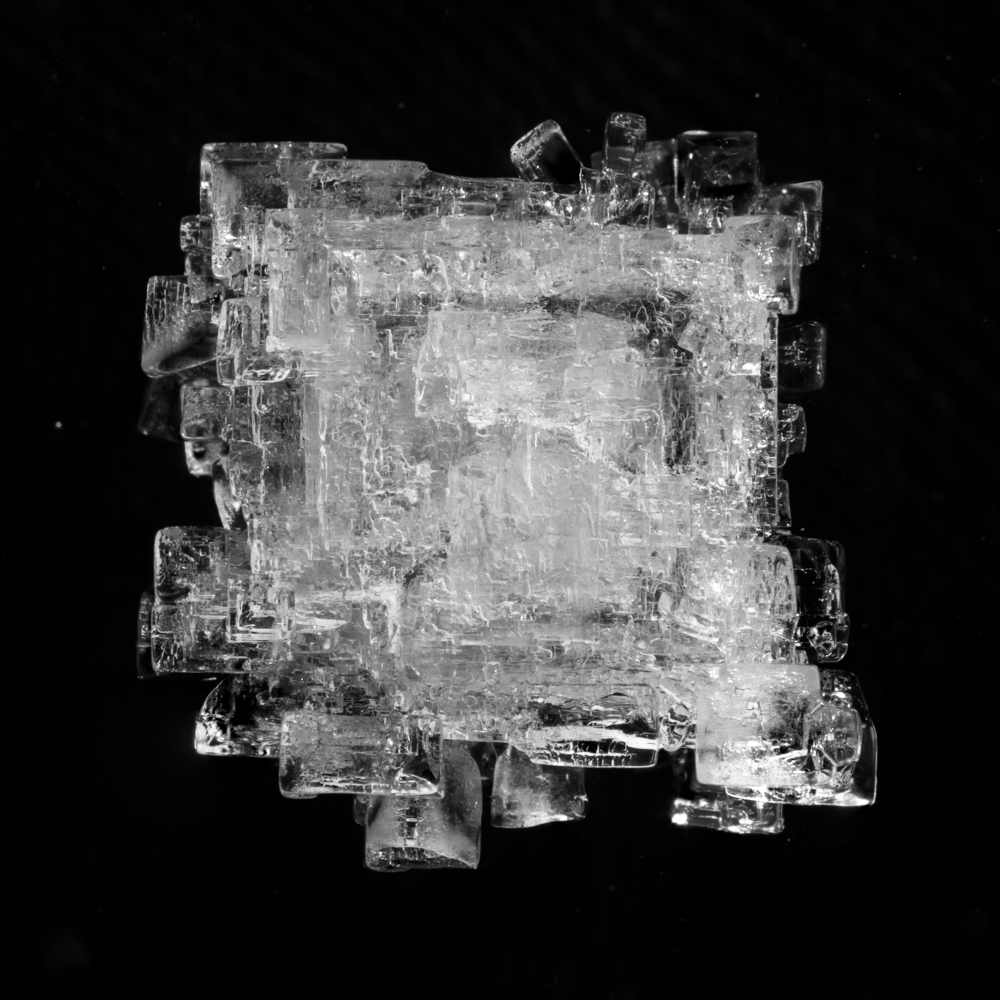

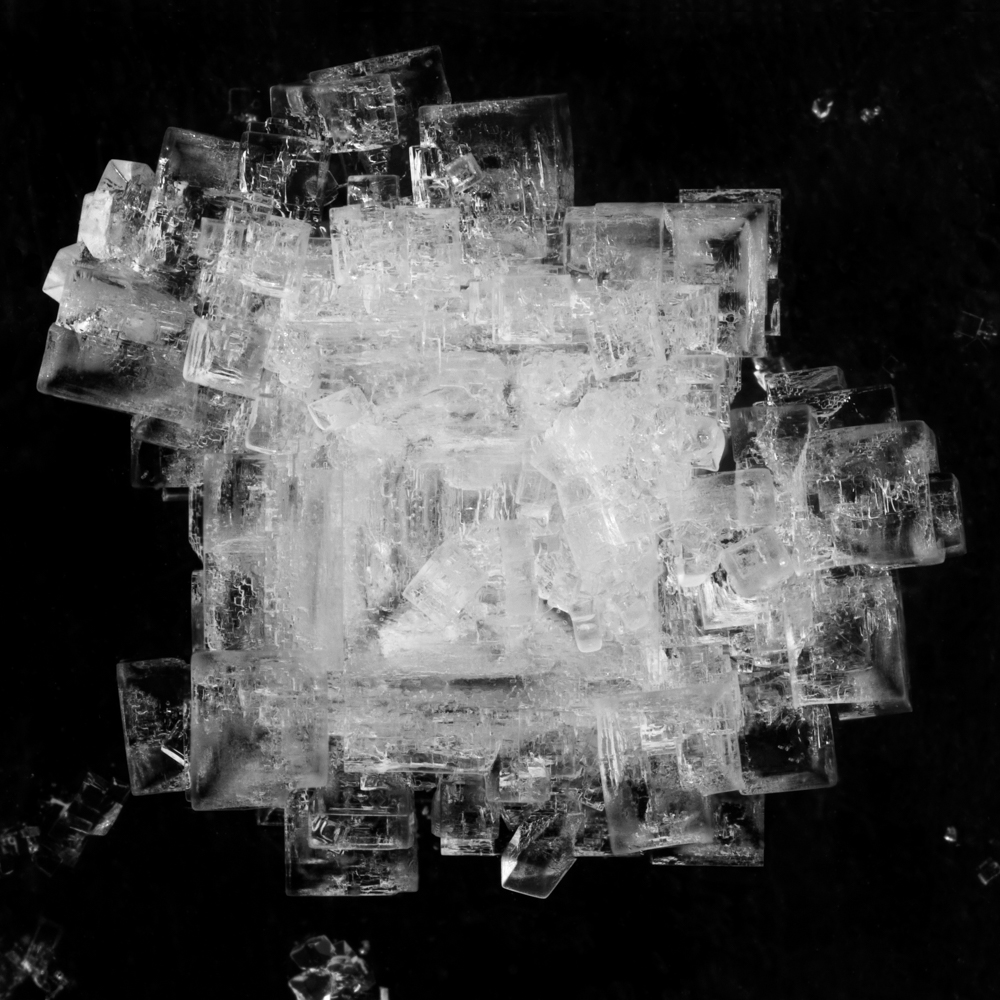

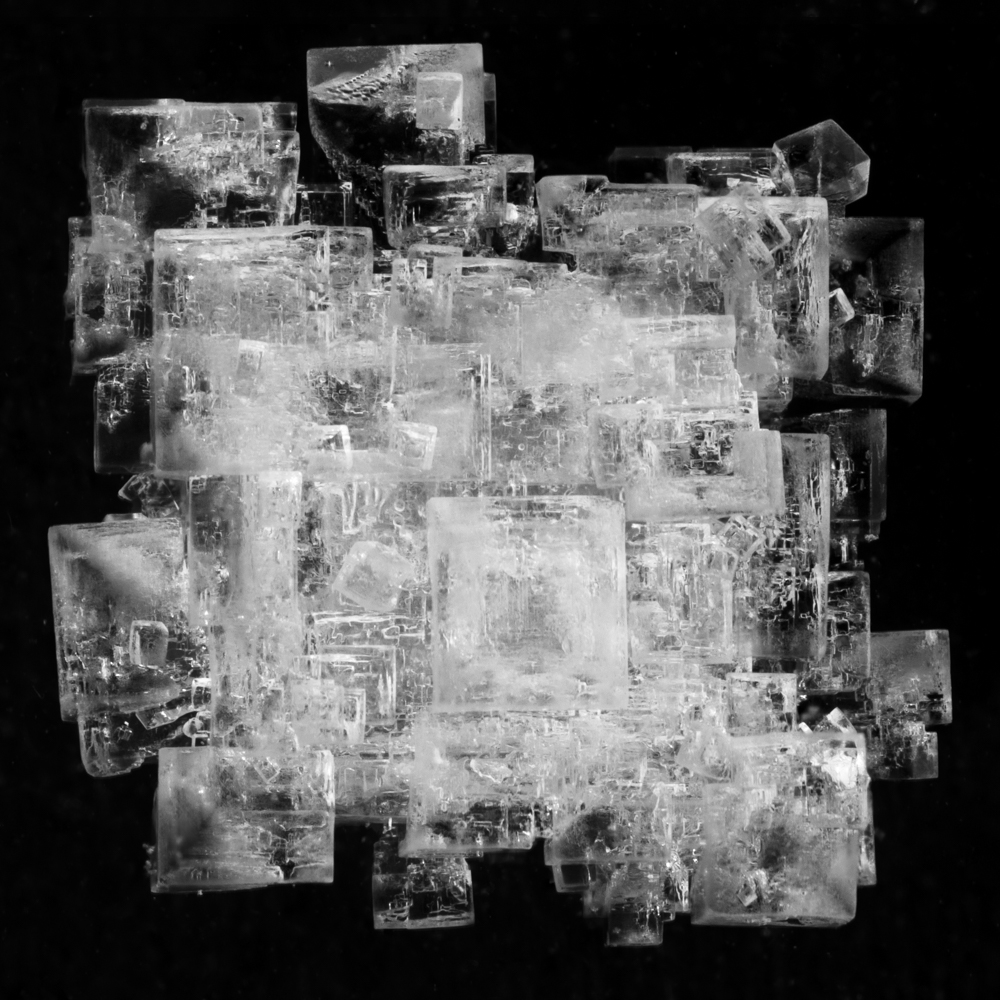

Salt is the commonest of common things. Essential as it is to human life, salt finds its place in countless metaphors. We can taste it when we can’t see it, in our tears, on our skin; it makes us thirsty if we have too much. As a mineral in the world, it has a sort of life of its own. Left to its own devices, salt fluctuates between visible and invisible, organizing itself into structures and patterns, and dissolving again. Under ideal circumstances, the mineral settles into clean-edged structures that maintain clarity and precise right angles as they grow. But circumstances are rarely ideal. Fluctuations in temperature or humidity, an occasional jostle, or pollution in the water will disrupt the crystal formation. Any state we witness is a moment from a process of becoming, and our own mutable nature is there, in crystals that never quite reach an ideal form.

Daniel George: This is your fourth project that focuses on salt. What initiated this interest? And what keeps it going?

Christine Lorenz: This series began with a science experiment. Some years ago one of my kids had been trying to grow a salt crystal, using the method taught in school, with a cup and a string. Nothing was growing, and he was running out of time, so we started looking for faster ways to get crystals to form. We tried putting some drops of solution on a pan in a very low oven. It worked! Some of the formations that resulted looked like they would be interesting subjects for macro photography. As I made more, they started looking like galaxies. This put me in mind of the Charles and Ray Eames film “Powers of Ten,” and the harmonies between micro-scale and telescopic scale. All of the poetic, cultural, and historical associations with salt seemed to open up from these strange, surprising forms and patterns.

When you can isolate salt in this way, and watch it for a while, it seems to be acting on its own, to have some motive to become something. It is fascinating to observe this process, and you can’t really control it. These qualities, coupled with how essential it is to our lives and health, and the way it flows through our bodies—this has all led to salt playing an endless range of roles in figures of speech, in poetry, parables and superstitions, as far back as writing goes. And of course it has been a cornerstone of commerce and trade throughout history.

One of the things that makes this so interesting has to do with what salt is in the earth, as opposed to what it is in our imagination. We all know salt as a consumable good, and consumer logic keeps our attention on how we can get a product and what it can do for us—not on where it comes from or where it goes. Where does it come from? It comes from the store. Where does it go? It goes away. But salt is a mineral that comes from the ground. Most of it is mined from enormous underground deposits; near where I live, for example, there are two mining operations that stretch for miles underneath Lake Erie. It took millions of years for that salt layer to accumulate. Salt mining is a massive industry. Humans are moving countless tons of salt at any given time, and only a very small fraction of that goes to culinary use. Most of it goes either to salting roads or to chemical processing. Geologists will tell you that salt and petroleum have a complex, intrinsic relationship, and in many parts of the world certain salt formations are signs of where oil and methane can be found. When we think about salt, all our poetic and cultural associations have to do with what’s familiar, which is what’s in our food—but all of that is only the tiny tip of the iceberg of human entanglement with the life cycles of salt on our planet. So for me, thinking about salt means thinking about perspective of time and scale, about visible and invisible, in the material as a mineral.

We’re all affecting the literal earth, this 4.5 billion year old earth, through our daily lives, in ways that are not visible to most of us. How are we supposed to deal with that? How are we supposed to even grasp it? Is it possible for us to think in geological time? I think it’s one of the great things about being human, to be able to exercise our imagination and our empathy in that way.

DG: How does Dissolution fit within and converse with these other projects?

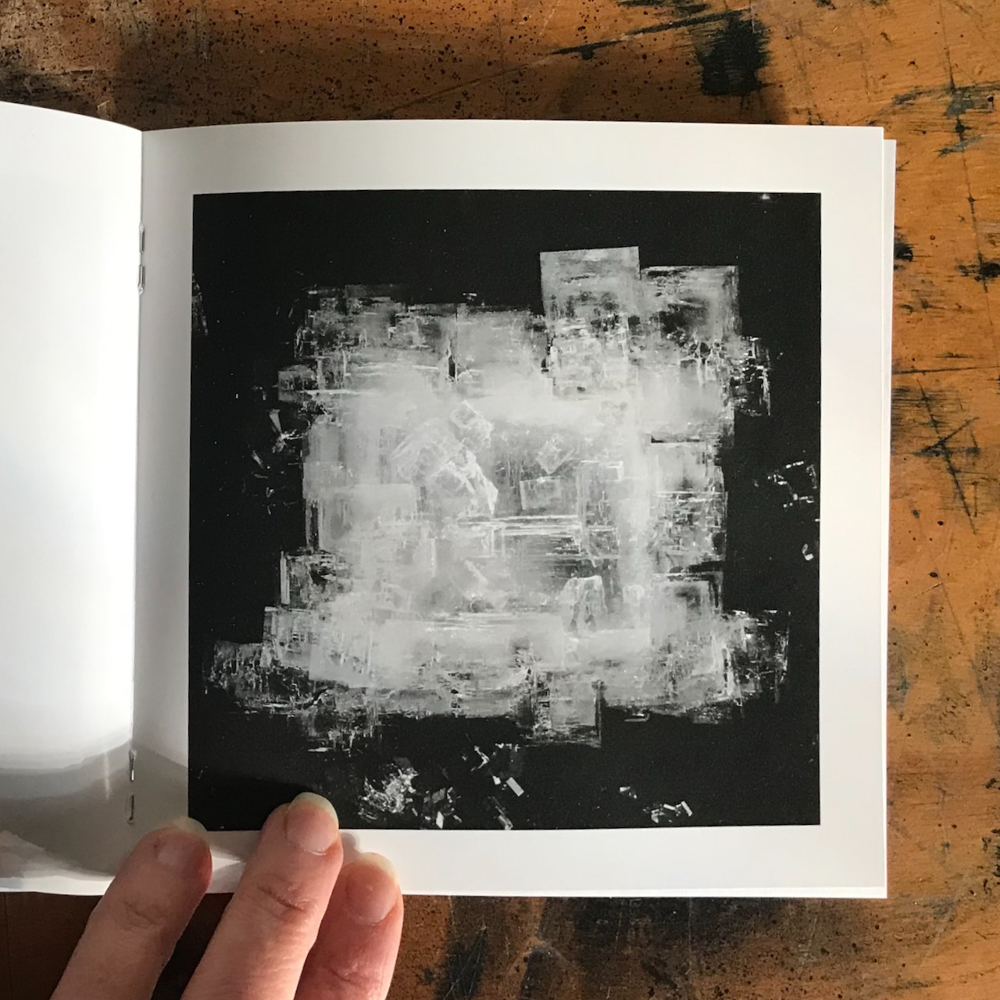

CL: The crystals you see in this series had been growing for a few months. I was getting ready to photograph them by transferring them into a tray with fresh saline solution. It turned out that the solution was not fully saturated, and the crystals began to dissolve. You can see it in the rounded edges and the places where they seem to be coming apart. I was in the process of editing the photographs of this group on January 6 of last year. I tend to see human-like qualities in the behaviors of the salt crystals, and when it looked like they might work together as a series, Dissolution seemed like an appropriate title.

The historic events of January 6 represent the threat of a different type of dissolution altogether. But it was one that I personally came to process through geological terms. On a human, social level, things build over long periods of time, and become so substantial that from one person’s perspective they seem stable, even inevitable. A solid foundation, so to speak. But then from a larger perspective, we sometimes realize very abruptly that we are part of things that are in flux and not permanent at all. This is frightening to observe. I don’t see beauty in it. We do our best to affect what we can, but we also have to find our own ways to come to terms with what we cannot change.

DG: How would you say these images, which isolate “a moment in the process of becoming,” more broadly reflect “our own mutable nature?”

CL: It’s a timeless question: in the big picture, what are we striving to become? If we could visualize what the shape of perfection would look like, would it have something to do with geometry? When it comes to abstraction, people will respond intuitively and in their own ways, and that’s part of its enduring appeal. Maybe it’s because I spend so much time watching these salt forms as they grow, but I come to empathize with them. They are formed by a constant negotiation between a drive to attain a kind of perfect geometrical form, and the forces around them that are always pushing in other directions.

This crystallization is a process that is slow from one perspective and fast from another, and the crystals can dissolve at any time back into a solution that can be dispersed, down the drain and out into the world, or it can be left to slowly evaporate and crystallize again. No state that we observe is ever a final state: it’s always a moment in a process that may be too slow for us to see. Photographs can capture that state, which is likely to be gone by the time we see the images.

DG: Would you mind sharing your process for making these images? Also, I am interested in hearing more about the photobook you created for this project.

CL: The crystals in the photographs come from ordinary materials. I dissolve table salt in boiling water on the stove, let it cool down, and pour the solution into different glass or acrylic vessels. Over time as the water evaporates, crystals form. The process of crystallization is affected by temperature and humidity, and since I do this in my home, both of these fluctuate quite a bit. The evaporating dishes are likely to get bumped, and it’s always possible that the salt will have traces of other minerals, or that something along the way wasn’t quite clean. As a result the crystals that form are never the kind of perfect cubes you’d hope for. There are always cracks, rough edges, opacity, and things coming together at funny angles. When the crystals form in contact with the air, a completely different range of possibilities emerges.

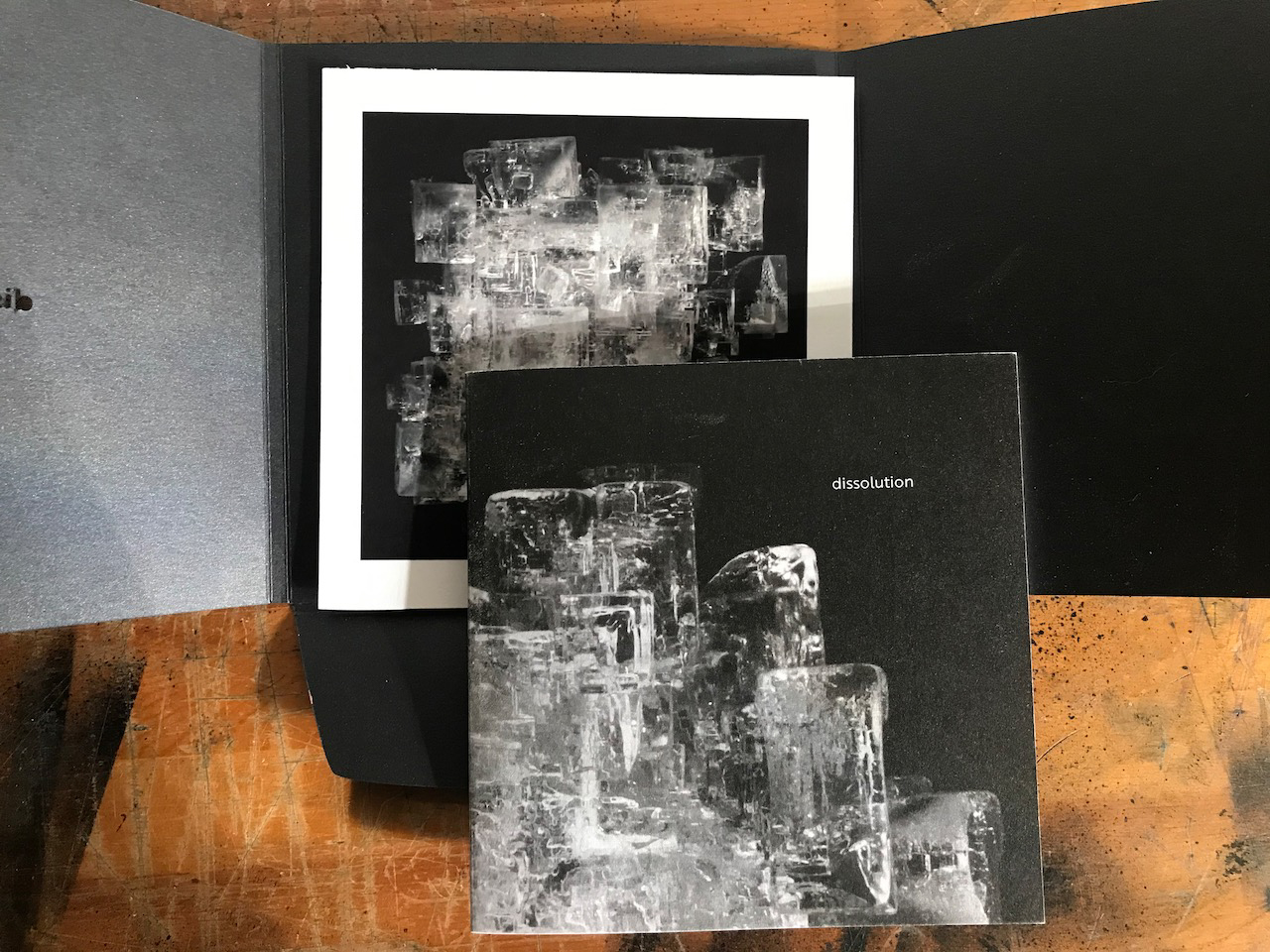

The photographs in the Dissolution series were made with a Canon 6D and a good macro lens, using a copy stand and a lot of focus stacking. The crystal formations in this group ranged from around 1/4” to 1/2” across. There are nine photographs from this series in the booklet, which is digitally offset printed. That process doesn’t quite do justice to the tonality of the photographs, so I also produced a limited edition of the book that includes a 6” square print in a custom-cut folder.

DG: You describe yourself as an examiner of the “ordinary, overlooked, disposable, and forgotten.” Could you talk more about this curiosity?

CL: I’ve always been kind of a scavenger. I never completely let go of that tendency kids have to empathize with the objects they encounter. Beyond a certain age, if you feel like you can have a real connection with a rock, you might be an artist, a poet, or a hoarder. But I think that tendency is worth paying attention to. We live in a world of interconnected systems, and we interact with objects in ways that go far beyond functionality.

I’m very interested in the kinds of connection people feel with objects—with things that bring us happiness, and things that have emotional significance to us, but also with things as things. To feel like a particular thing deserves to exist, and merits attention, is to grant it a kind of life. I’m interested in what kinds of things seem alive to us, what kind of things don’t, and how those feelings affect how we act upon the world.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 2November 27th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 3November 27th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 4November 27th, 2025

-

Nancy E. Rivera: No Present to RememberNovember 22nd, 2025

-

Astrophotography: Molly WakelingNovember 6th, 2025