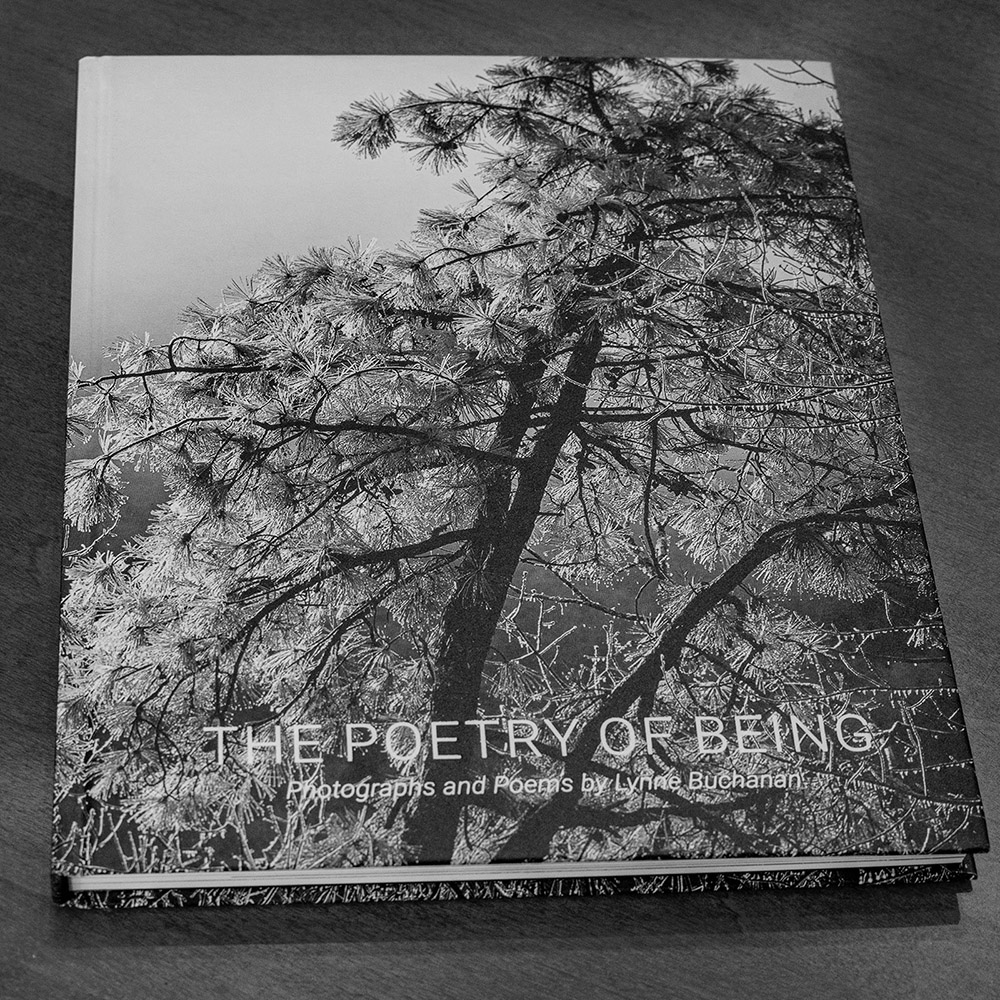

Lynne Buchanan: The Poetry of Being

For many, the idea of nature and literature go hand in hand. The stillness of a book in one’s hands versus the wildness of nature creates a dichotomy that together heals one’s very soul. When I was first approached by Daylight Books to review Lynne Buchanan‘s newest photo book, I was elated. To combine the idea of the natural world within a book, spoke to me before I ever received a physical copy. Lynne Buchanan has beautifully composed the feeling of deep isolation that occurs when the world ceases to exist for a time, all within 112 pages. Between platinum palladium prints of the natural world, we are gifted with haiku that endue the viewer with feelings of darkness at the challenges society is faced with. Never before have I been impacted by the images of nature in this way. I find myself continuing to comb through the pages, finding something new with each look. To open The Poetry of Being is akin to coming home, to grounding oneself within the images and words on the page.

The photographs of award-winning artist Lynne Buchanan have been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions in museums and galleries across the United States, as well as in Athens, Greece and Barcelona, Spain. She received Honorable Mention in the alternative process category for the Poetry of Being series in the Julia Margaret Cameron Awards, and her Wanderings in Wild Places platinum-palladium series received Honorable Mention in the Pollux Awards. Lynne latest book, The Poetry of Being, includes photographs and haikus and was just released by Daylight Books in June 2023. Lynne is also the author and photographer of Florida’s Changing Waters: A Beautiful World in Peril, which was published by George F. Thompson Publishing in 2019. She had the honor of presenting her Florida’s waters book at the Miami Book Fair, as well as at the Society for Environmental Journalism and the North American Nature Photography Association’s Summit. Lynne has also published articles for Waterkeeper Magazine and her work has been featured in numerous magazines. She is the recipient of masters degrees in art history/museum studies from George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and in creative writing from the University of South Florida in Tampa. She also received a bachelor’s degree in art history from New College in Sarasota, Florida. Her mentors in alternative process photography and platinum palladium printing are Jill Enfield and Pradip Malde.

Follow Lynne Buchanan on Instagram: @lynnebuchananphotograph

The Poetry of Being

I was inspired to begin this series of images during lockdown in the first Covid wave, when I was seeking to stay connected with life in a period of profound isolation. For four months, I took my elderly mother out of her congregate living facility and into my home to keep her safe before vaccines became available. At the same time, some family members and friends were seriously impacted by the pandemic both physically and mentally and also required my support.

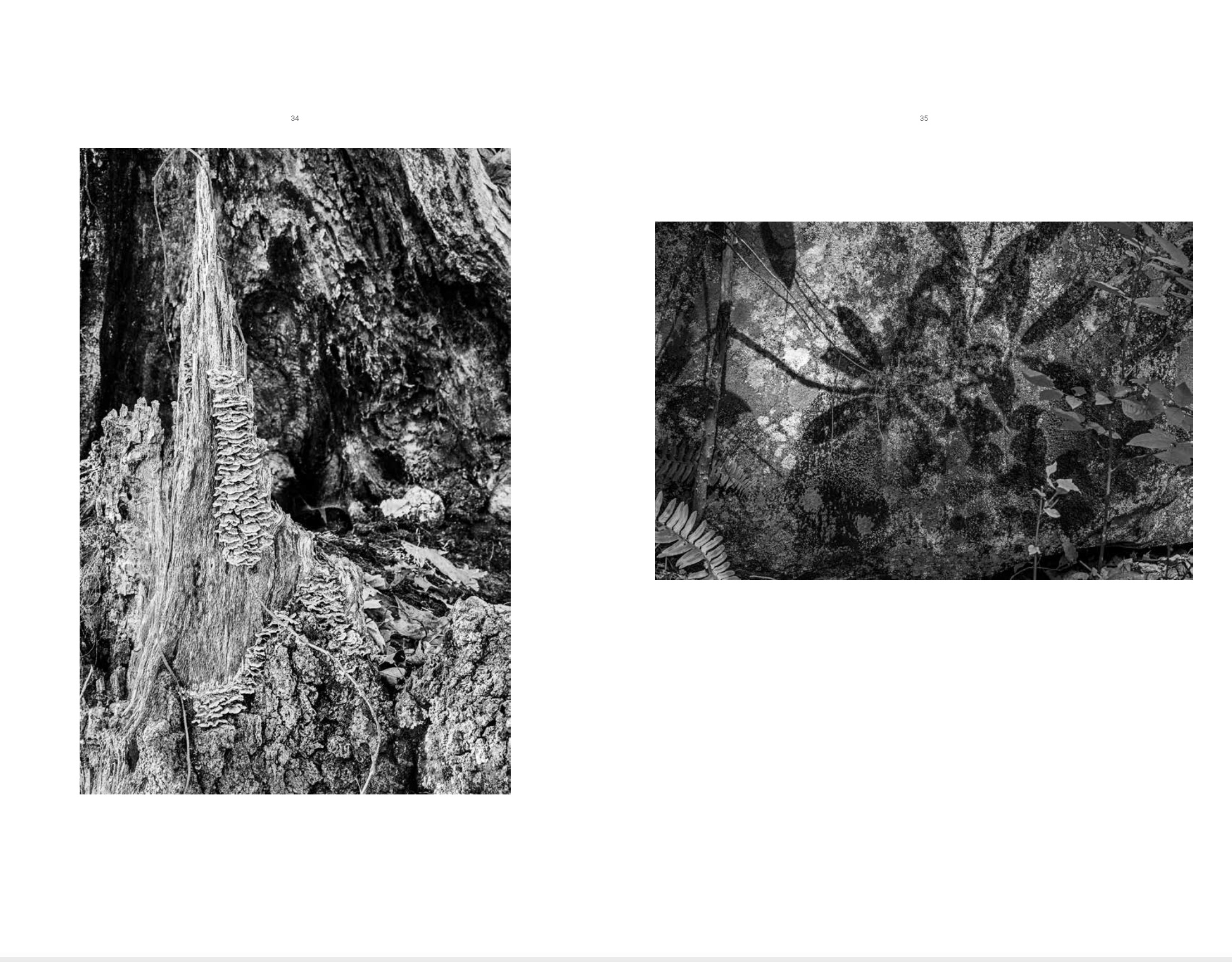

Photographing daily on my mountain ridge and in nearby natural areas made and continues to make me feel more balanced and grounded. When I witness aspects of nature that have hung on through illness and physical harm, it gives me the strength to keep going. Nature heals my soul by reminding me how interconnected existence is, and how traces of energy remain and future growth is supported even after lifeforms return to the earth. The often lyrical way Mother Earth teaches us about the stages of life and death helps me live with what is happening to the planet and cope with mortality. Photographing ordinary things in my immediate environment taught me compassion for all living things, especially those that have been harmed or are different, as well as how to celebrate every stage of being, including the transition to non-existence.

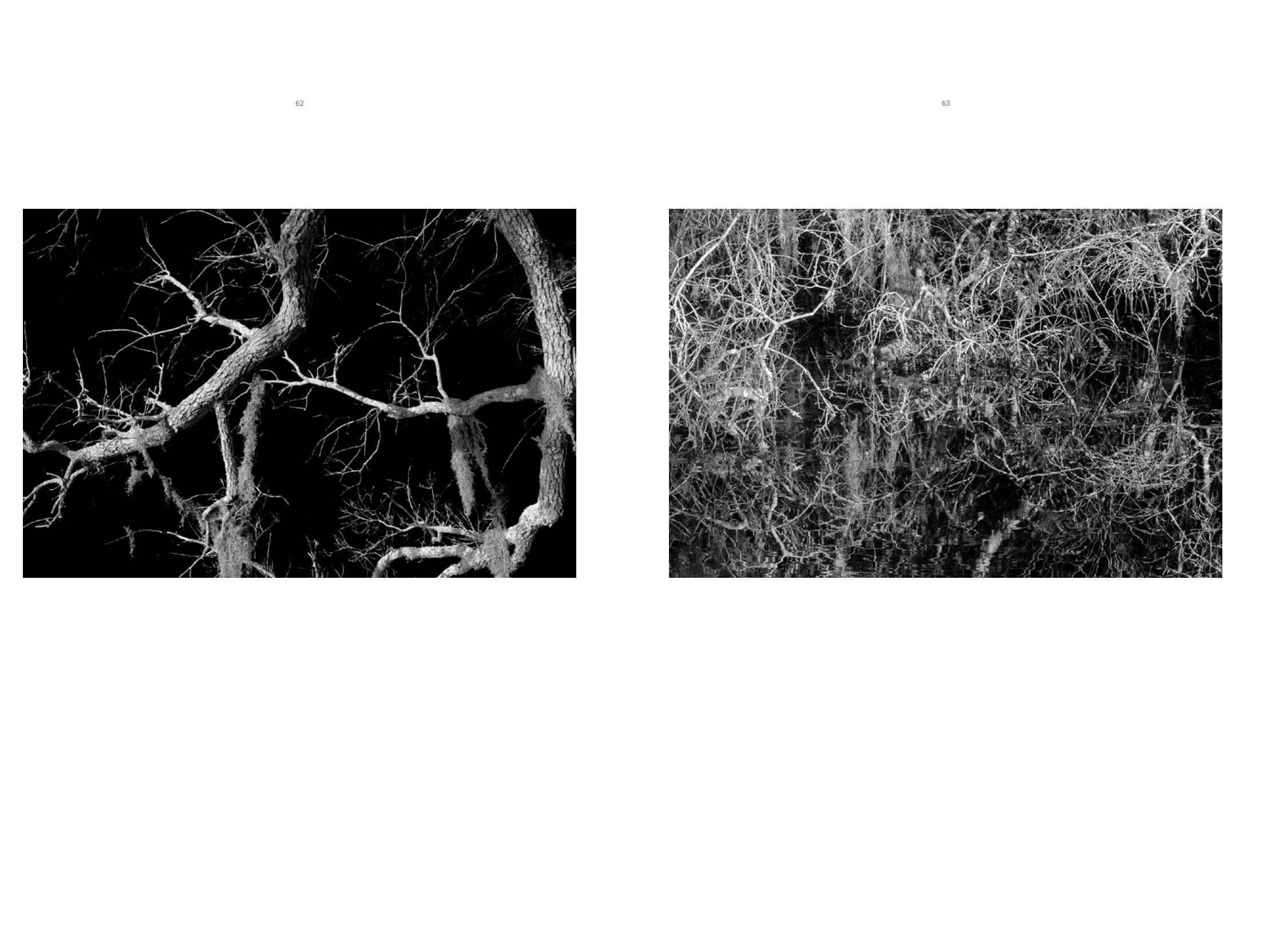

As I age, I find I am more interested in expressing my emotional response to the fragility and perseverance of nature, versus an idealized version of the environment. My images include traces of what was, things still hanging on, the effects of climate change and human impact, and the cycle of life which includes decline and death, while also celebrating the commonplace since all of life is precious. I am drawn to burls, scars, and other physical disconformities that evoke a history of experiences.

The magic of light is always a focus, whether it is how it can transform the ordinary into the extraordinary or whether it evokes the manifestation of the spiritual in the material. Shadows are important too, as light would not be known without darkness and aspects of scenes that are not yet fully illuminated contain emergent possibilities.

Time is a unifying theme, because my photographs celebrate the present, while including elements such as roots that suggest the past, water which is a continuum, and paths that serve as portals leading to a more hopeful future in these challenging times.

In making these images, I strove to convey the lyricism of being and to create art that by-passed labels and my analytical mind and went straight to the heart of what is. Less increasingly became more, and explicative language began to feel inappropriate when attempting to describe why I was drawn to certain subjects. I began forming haikus in my mind as I was looking at the landscape before me. The idea for a book began to percolate.

The darkness of the times led me to switch from color to black and white, although I still photographed in color and then converted the images to black and white in post processing. Part way through the project, I decided that the shadows might contain the answers, or at least help define the questions which are always more interesting. The every day world became increasingly magical while I connected with the ground of being, as Heidegger described it almost a century ago. I began making digital negatives, so I could make platinum-palladium prints and literally watch the images come into being as I exposed them to ultraviolet light and then submerged them in the clearing baths. Although additional prints can be made from the negatives, the process makes each one unique as are the subjects they depict. The richness of platinum-palladium printing imbues darkness with its own beauty and the use of noble metals both preserves transitory states and underscores how valuable all of existence is despite or perhaps because of its impermanence. -Lynne Buchanan

Kassandra Eller: Thank you, Lynne, for agreeing to this interview! This book is deeply impactful and how you have photographed nature in this way is profound. I wanted to start our discussion by diving into your photographic journey. When did you become interested in photography and what led you to where you are today?

Lynne Buchanan: I have always taken photographs of my family and places we traveled to and have countless photo albums. I didn’t want to forget all of the special moments, even the most ordinary ones, that constituted my life and I knew my children were growing up and they’d be out of the house living their own lives before I knew it. It wasn’t until 2011 that I became seriously interested in fine art photography though. I attended a workshop with Clyde Butcher at his gallery in Big Cypress immediately following a yoga intensive I’d gone to in Miami (I’d also recently completed yoga teacher training). Clyde switched from color to black and white photography after his son was killed in a car accident and he moved to the Everglades to live in solitude and heal through being in nature. He told us to walk into the wild with our arms open and orient from our hearts, which really spoke to me. I was so thrilled with what I noticed and learned being in nature with a camera that I ended up leaving my job as a commercial credit analyst at a bank to pursue photography, while also continuing to teach yoga. Two years later, Clyde had a show at the South Florida Museum and the museum put out a call for photographers for a group exhibition called “Walk Slowly, Look Closely.” I submitted some photographs and they said they loved them all and had a hard time deciding which two to use and ended up offering me my first museum exhibition in 2013. That show was called “On the Rivers of Florida: Lynne Buchanan’s Photographic Meditations.” (The curator was pleased with that exhibition and he offered me a second exhibition in 2015 of my color Cuba photographs at the same time Clyde was showing his black and white prints of the Cuban landscape.)

I grew up in Florida and had always loved the rivers there. While I was photographing for my first solo exhibition, I noticed that the water was in trouble in many places and I approached the curator to see if he would be interested in exhibiting photographs showing how the water was changing. In 2016, I had my third solo exhibition at the South Florida Museum, It was called “Changing Waters: The Human Impact on Florida’s Aquatic Systems.” After the exhibition came down, I kept photographing water in Florida for several more years and in 2019 I published a book with George Thompson Publishing entitled “Florida’s Changing Waters: A Beautiful World in Peril.” The photographs in the book were taken over six years and I worked with Dr. Robert Knight, the head of the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute, Jason Evans, an environmental sciences professor at Stetson, members of the Waterkeepers organization and indigenous people around the state. I also began photographing biodiversity to contribute images to an organization formed through the University of Florida. While I was working on the water book, I learned a lot about cyanobacteria in the waterways, salt water intrusion into wells, sea level rise, and other issues affecting the state. It concerned me so much that I decided to relocate to the Asheville, North Carolina area where the water quality is much better and there is more biodiversity.

My interest in water and environmental issues led me to travel to Bangladesh in 2018 to work with the Waterkeepers there. I was interested in seeing what happens when water quality is seriously impaired, and I discovered many rivers no longer had fish. In addition, Bangladesh is frequently referred to as ground zero for studying the effects of climate change and sea level rise. In 2019, I went to Antarctica to photograph the melting sea ice and emperor penguins, which are also at serious risk from the effects of climate change. While working on all these projects, I developed serious eco anxiety, so in the summer of 2019 I went to Wild Rice and took a workshop with Douglas Beasley entitled the Emotional Landscape which totally shifted my work and it became much more personal. Around this time, I switched from color to black and

white photography. My work went from being a more documentary record of what was happening to the environment to expressing my emotional responses to the changes. I also attended an 8-week workshop with Jill Enfield on alternative process photography at Penland and that is when I discovered and fell in love with platinum palladium printing. After I left Penland, Jill introduced me to Pradip Malde who became a mentor and helped me refine my process.

KE: I see in your bio that you received an MA in Creative Writing. In this book I can see that your writing complements and drives meaning into your photographs in a beautiful way. When you are photographing do words come to mind and help you form an idea of how you want a photo portrayed? Do you feel as though your background in writing informs your photographic work and the way you present it in any way?

LB: I have always loved writing, but I actually stopped writing for a long time after completing my masters degree. I have heard that happens to some people. However, I did continue journalling and I believe that writing motivated me to explore what my observations meant to me. I didn’t come back to writing anything more than blogs until Covid, when suddenly I felt a strong desire to write poetry again. My mother was suffering from heart failure during that time and has since passed away. A family member also developed Long Covid and I could only communicate with him in one sentence texts for a long time. That inspired me to start writing haikus, because I wanted to strip away all inessential clutter in my brain and get at the essence of what it meant to be alive, to suffer, and to find hope. I signed up for a workshop with Natalie Golderberg and Eddie Sollway called “Perspectives–Three Simple lines and the Color of the Wind” on photography and haikus. Sometimes, I go into nature and haikus come to me while I’m connecting with the landscape and that influences how I frame and compose my images. Other times, I’ll photograph something because it calls to me on an emotional level, and the haikus come later. Even when I don’t write anything and just photograph, my work is still lyrical and bypasses my analytical mind so that my perception is linked with the subjects I photograph in a more poetic way. When my photography had a more objective and environmental bent, I was making images of specific things I saw like cyanobacteria, pollution, and sea level rise. However, lately I’ve decided that our environmental issues are the result of a crisis of intimacy, as my colleague and friend Susan Patrice has also commented. Now I’m more interested in expressing my emotional connection to places and how their health and survival strategies hurt or inspire me. There are a lot of reparations I feel we all need to make to the land as well, and my work is one way I’ve found to honor nature.

KE: It seems as though this project originally started as a way for you to explore and “break away” from the reality of the pandemic. At what point did this become a project and when did the idea of a book begin to form?

LB: Working on this project was a lifeline for me. The pandemic affected all of us in profound ways and brought facing our own mortality into focus. Walking in nature was grounding and balancing, but it also enabled me to connect with the cycle of life in the natural world and somehow make sense of what was happening in the human sphere. The idea for a book began to percolate when I saw the connections between the poems and photographs I was making. I hoped putting them together in book form and sharing what helped me keep going would benefit others since all our lives were upended and so many people seemed to be suffering.

KE: Light seems to play a big part in this project, so much so that you mention it in your statement. I loved how you said “light would not be known without darkness.” It seems as though in your images you play with the dichotomy of light vs shadow. Would you elaborate on why you chose to use light in this way and pair photos with each other based on this?

LB: My yoga practice has always taught me to seek the light, especially in dark times. And it also taught me the importance of acknowledging the shadow side, because when we don’t have the courage to look into the darkness it can overwhelm us. When I was in college, I studied Jungian psychology with one of his former students and am very familiar with the concept of shadow work. Sadly, it appears many in our society are not. I made The Only Choice is to Follow the Light, the opening photograph in the book, to express my need to keep focused on the light and hope during Covid and at a time when political tensions were getting in the way of finding the best course forward. I also believe we only know the light from its relation to darkness. I recently made an image called Grace of a Sessile-leaf Bellwort flower along the Bartram Trail in North Carolina. These flowers grow under the leaves and are also connected underground through a network of rhizomes. The flower I photographed was so delicate and small and it touched me how it was shielded by its own leaves and those of nearby flowers of the same species. When I began processing the photograph in preparation for making a platinum-palladium print, I realized that the light reflected by the delicate flower touched me emotionally when I considered its relation to the shadows around it. That really is the definition of grace–being able to shine when times are the most difficult and not allowing the world or life to break you. We can’t prevent darkness and challenges from occur. All we have control over is our response and acting with grace reduces internal strife and can inspire other to be their best selves as well.

KE: Due to the black and white nature of these photographs, there is a sense of reflection and a serious nature to the images. I see in your statement you originally shot these photos in color. Did you switch to black and white in post-produciton as a way to portray your state of mind in that moment?

LB: Absolutely. My Florida’s changing waters work was all in color because I wanted people to see what was happening to the water and to make the images closer to what they would see if they were traveling down the same waterways. I wanted them to believe that my photographs were an accurate reflection of the objective state of things, and not an alarmist exaggeration. The Poetry of Being is about my emotional and intimate connection with the environment and my feelings about what I was seeing. Even though it is highly personal work, I hope it provides a doorway for others to connect with the natural world in their own intimate ways. Black and white imagery always feels more emotional to me, and it also removes subjects from a purely objective realm where we identify and dismiss things once we’ve categorized them and never truly allow our encounters to change us. Tim Carpenter recently published a remarkable book, To Photograph is to Learn How to Die, in which he stresses the importance of why we photograph and connect with the world in the ways we do, instead of what the photographs are of on a strictly literal level. Since I began photography, I have been attempting to make images from a place of immersion and connection, rather than standing outside looking at the world. Tim’s book draws on philosophy, poetry, psychological perception, music, and other creative pursuits that help us come to terms with our own mortality, so we can ease the ache caused by our awareness of it. That was also a goal of mine in making this book. Not only do black and white images remove subjects from their ordinary context, they also prioritize light and shadow and connect us more directly with the internal workings of our psyches.

KE: The haiku you have written are so beautiful. I find myself continuing to go back to go back to read them. With both photos and poems to consider, how did you decide the sequencing of your book?

LB: I started The Poetry of Being in a year-long bookmaking class with Elizabeth Avedon through NORDphotography. She astutely suggested that I not pair every image with a photograph, even though I had written haikus for many of the images that are in the book. If I’d included one for each image side-by-side, it would have made people begin to expect the pairings and then people might skip them or not look at the photographs as closely–sort of like what happens in a museum when people’s attention is divided between reading wall labels and looking at the images. Although I wrote many haikus on location, they often ultimately pertained to more than one image so including them more sparingly made the most sense. I was fortunate to work with the very talented designer Ursula Damm at Daylight. I sent her a layout I’d come up with and then I sent her more images and haikus. She kept most of my pairings, but she moved a few of the poems and haikus around and knew how to pace the reader’s experience appropriately. I liked her approach. We worked back and forth until we came up with the final sequence and I think it works well.

KE: Alternative process photography holds a special place in my heart because of the intimate nature of how the photographer interacts with their images. During the process of platinum printing, did you run into any unexpected outcomes? In your opinion, how did the use of an alternative process drive this project forward?

LB: My mother was dying of heart failure during Covid and developed vascular dementia. She couldn’t remember how to use a telephone or turn on the TV and she was helpless without others to assist her, but her mind was in tact enough to recognize how impaired she was. It was heartbreaking to witness. Yet, she was able to appreciate flowers, blades of grass, and the smallest natural details in her shrinking world. She hung on to life with remarkable tenacity for as long as she could. I often thought of her as one of her flowers innately reaching for the light to keep her life force energy going. I took her for walks almost every day, so that she could connect with what she could still appreciate and what brought her joy. She often pointed to things she wanted me to photograph and in so doing she taught me to see how extraordinary the most ordinary things can be, since everything is a manifestation of life and spirit. Platinum-palladium printing dovetailed with what I was experiencing through my experiences with her perfectly. After I placed my digital negatives (made use the Piezography system from Cone Inks) on paper coated with sensitizer and exposed them in a UV light box, I would watch spellbound as the images came into being. The richness of platinum printing imbued darkness with its own beauty and the use of noble metals both preserves transitory states and underscores how valuable all of existence is despite, or perhaps because of, it’s impermanence. A blade of grass or jewel-like water droplets on a trumpet vine appeared sacred when printed through this process, because of the shimmering qualities of the medium. Actually, all life is sacred all the time, but we have been conditioned to seek out grand vistas and the sublime and frequently consider aspects of life we see every day as lesser in value and disposable. One important unexpected outcome is how incredible the blacks are and what we can see in them the longer we look. In inkjet printing, the blacks can appear blocked up, but the more I worked with this process, the more I felt I was looking at a Rothko painting. In both instances the longer you stare at the images and allow your eyes to adjust to what is surfacing, the more you see and a spiritual presence seems to emerge.

Making a book based on platinum-palladium images can be challenging since this medium has a distinctive look that is quite different from silver prints or black and white inkjet images, but Ofset Yapimevi in Turkey did a fantastic job. We printed the book in quadtone on Munken Pure Rough paper, which is the closest paper I could find to the Revere Platinum paper I make my prints on. I sent them my platinum-palladium prints and they sent back sheets with offset test prints and then I sent the sheets back with my comments. They then modified the prints and I think the images in the book successfully mimic the look and feel of platinum-palladium prints. I am grateful to Daylight for going the extra mile with this and I think it was worth it.

KE: I have found that the projects I take on often become a way to process my emotions. It seems as though The Poetry of Being has acted in the same way for you. Did this project become a therapeutic way of understanding your emotions and thoughts during the pandemic?

LB: Yes it did. Not only was I facing my own mortality, as we all were and ultimately always are, I was doing my best to help keep my elderly mother safe and help family members who were also impacted. I had to be strong for everyone and as reassuring as possible, even though the world was turned upside down. I walked by this one tree on my mountain ridge every day that had been struck by lightning and had bark that was peeling off as a result. The bark hung onto the tree for more than a year, and whenever I saw it still hanging on it gave me the strength to keep going. I’d also go into the woods and observe fungi breaking down fallen tree limbs and I understood that food was being provided to the forest and that energy remains even after organic matter dies. That was reassuring to me while processing the realization that my mother would not be with me much longer. It also helped me understand that life and death are natural cycles, even though the onset of the pandemic and the large number of deaths that resulted, was an extraordinary occurrence that shocked everyone. Grasses and small plants reaching for the light helped me connect with an intrinsic desire to live that exists in all lifeforms, including myself, and motivated me to take care of myself and my family as best I could so we could all get through these challenging times.

KE: Due to the nature of this work it feels as though this project could continue on. How did you know this was a completed project? Did there come a moment where you knew that you were finished?

LB: This project changed the direction of my creative process and I feel there will always be elements that surfaced here in my future artwork. My images became more lyrical, philosophical, and emotional and I don’t think I would be satisfied returning to a more documentary approach. I am much more interested now in how what I encounter in the world reveals things about myself and meanings that are intimated beyond what is contained within the frame itself. In addition to the poems included, the images themselves feel poetic to me. When poets go into the forest, they do not analytically label what the see and then write about it. They feel their connections with the world and the essence of what they encounter intuitively in ways that transcend categorization. The philosophical aspects of this work focus on how we perceive the world phenomenologically and how we know ourselves from being in the world and how this contributes to our understanding of being itself, our mortality, and all the big questions. The emotional aspects pertain to how the extremely vulnerable aspects of nature can touch our core and how beauty can be heartbreakingly touching, because it is as impermanent and fleeting as is life itself. So going forward, I know the depth of what I learned and experienced working on this project will always be part of me and contribute to how I perceive the world, my own being, and life itself.

There wasn’t one moment when I thought this project was completed. It was more of a general feeling as vaccines became available and our horizons began to open up again and we could see friends in small groups once again. This work was highly personal and arose from being profoundly isolated. It was a way for me to forge connections with something larger than myself. I frequently felt that if I didn’t go into nature, I would become lost in my own worries and lose perspective. Many people who have looked at the book have told that it makes them feel better and more grounded, even though there is a much darkness as there is light. The book focuses on the immediacy of the present moment and and an underlying life force energy. We weren’t making plans for the future, we were all just trying to survive. When things began to open back up and it seemed that we might be able to resume our lives, albeit in a new fashion, that is when I felt the intensity of my thoughts and feelings shifted and this body of work was complete.

KE: Is there anything you are currently working on?

LB: I am always working on several projects at once. One project I’m working on is Lessons from Wanderings in Wild Places. During this Age of the Anthropocene, most of the natural world we encounter has been altered by the hand of man. Indeed it could be argued that no place is safe from how our actions have altered the earth. However, there are still places that are more wild and there are many lessons we can learn about how Mother Nature and elements of ecosystems interact to help each other live sustainably. We also learn a lot about ourselves when we go into wild places, as our encounters can be both sublime and frightening, since potential dangers are always lurking. I am also interested in exploring how often we are afraid of the wrong things when we go into nature, and while we are worrying about something we think we should be fearful of something else can get us if we don’t have all our sense attuned. How I will integrate all these layers in my images is a work in process.

On the more objective end of my work’s continuum, I’m photographing old growth forests in Western North Carolina and in other parts of the country and around the world. We are losing old growth forests at an alarming rate. This is problematic because they not only sequester a lot of carbon, the legacy they leave in the soil contributes to the health of new trees that grow nearby and helps these forests withstand the effects of climate change better than younger forests can. For the past six months, I’ve also been photographing the North Carolina section of the Bartram Trail for an exhibition with the Kinship Photography Collective that is opening this month and will be on view in Highlands, North Carolina through January 2024. The trail follows the approximate route naturalist William Bartram took between 1773 and 1777, when he trekked from North Carolina to Florida through several southeastern states.

A more personal project I’m working on has to do with my family’s history as seen through the lens of old photographs, objects, and stories that have been passed down to me that reveal clues about my past and the cultural influences that contributed to the formation of my identity. My mother was English and my father was of Swedish descent. As they were approaching their deaths, I asked them many questions and tried to learn as much as possible before they passed, but there are still so many missing pieces. I realized that I am the holder of much of the past for my children and that when I am gone, they will lose even more pieces of the jigsaw puzzle that is our personal history and cultural legacy. Our society is promoting an amnesia of the past, which I believe can be dangerous. My yoga practice taught me that appreciating the now is important, but there are also lineages that are important to understand if we are to avoid repeating the same mistakes. Our belief systems are passed down to us, and just like our shadow sides, we need to know what they are if we wish to consciously accept or reject them and life meaningful, more ethical lives.

KE: Is there anything else that you would like to add?

LB: Your questions were fantastic and really prompted me to think deeply. I can’t think of anything more to add at the moment, but if you have additional questions after reading this feel free to contact me.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025

-

Mary Pat Reeve: Illuminating the NightDecember 1st, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025