Hiroshi Watanabe

It’s not a secret that I think Hiroshi Watanabe is a photographic treasure, and he has recently been given an opportunity that doesn’t come around too often. Hiroshi was given a commission by the San Jose Museum of Art, in California, to explore their Japanese community through his photographic vision. 19 prints from the commissioned work were purchased by the museum and 9 are on view as a part of the current exhibition, DEGREES OF SEPARATION: CONTEMPORARY PHOTOGRAPHY FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION. There will be a private reception at the museum on January 4th, in the 2nd floor north gallery.

I was especially drawn to this work because, as a Californian, have always felt a sense of disgust concerning the WW2 internment camps that were located up and down the coast, and have had a long time appreciation for Takahashi Birds, created in the camps that are now highly collectible.

Hiroshi was born in Japan, and graduated from Department of Photography, College of Art, at Nihon University. He moved to Los Angeles after graduation and became involved in the production of TV commercials, eventually working as a producer. He later established his own production company and produced numerous commercials. He received an MBA degree from UCLA Business School in 1993. In 1995 his passion for photography rekindled, and since then he has traveled worldwide extensively, photographing what he finds intriguing at that moment and place. In 2000 he closed the production company in order to devote himself entirely to the art and became a full time photographer. He now divides his time between Japan and Los Angeles.

In August 2009, I received a commission project from San Jose Museum of Art. The project was to photograph the city’s Japantown. I was told I had the freedom to photograph any subjects as long as they relate to Japantwon of San Jose. Soon after I flew to San Jose and visited Japantown for the first time. From what I have researched, I knew Japantown was much smaller than the ones in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

But I didn’t know how small it really was. The area was only 4 blocks by 2 blocks and on its streets are some restaurants, markets, shops, and other businesses—mostly Japanese related, but the streets looked like any small business streets in the US except some monuments of Japanese internment during the World War II and a Japanese temple on one of the side streets. The streets were relatively quiet and there was not much going on.

On the first day, I walked around and I could not find anything distinctive or striking enough to take pictures of. I started to think that I might not be able to come up with good enough photographs for the project, and I started to worry.

Before I flew to San Jose, the museum gave me names of a few key individuals of the community. One person was Jimi Yamaichi, Director and Curator of Japanese American Museum of San Jose. This small local museum was temporarily closed for renovation at that time. I met Jimi and he showed me the museum building which was still under construction and there was nothing inside.

I asked him where items of the museum were and he told me they were in the storage. The storage was actually two old garages in the back of the under-construction building. He opened one of the doors and told me to follow. Inside was full of dust-covered old cardboard boxes randomly piled up everywhere. He held one of the boxes and explained that inside the boxes were things from the internment camps where the Japanese were forced to stay during the war. Some were things people used and some are what people made during such confinement.

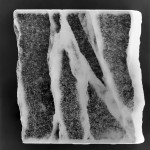

I noticed one flower brooch. It was beautiful. Looking at it carefully, I noticed that the flowers were made with tiny shells. Jimi explained that where the internment camps were mostly dry lakes and dry lakes used be bottom of the ocean and that if I dig dry lakes I will find many sea shells underground.

He said because people were not allowed to go outside, they used whatever they could find inside the fence on the dry land. Many World War II internment camp survivors now reside in San Jose area, and many items were their belongings, I was told. I thought then things inside these boxes could be the essence of Japantown and I decided to search what else are inside these boxes.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Sunjoo Lee: Untold

October 20th, 2025 -

Suzanne Theodora White in Conversation with Frazier KingSeptember 10th, 2025

-

2025 PPA Photo Award Winner: Teela Misa DeLeónSeptember 5th, 2025

-

The 2025 Lenscratch Honorable Mention Winner: Montenez LoweryJuly 26th, 2025

-

LUMINOUS VISIONS: Shoshannah WhiteJuly 17th, 2025