Considering the Past

I’ve been thinking a lot about how our work ages and how that patina of age effects the way we look at photographs. Recently, I have noticed that photographers are submitting to competitions with work that is sometimes two to three decades old. And those portfolios are often getting a lot of attention. Christine Osinski’s wonderful work from Staten Island in the 1980’s was presented a Photo Nola last year and it garnered an exhibition in New York this past fall and representation with the Sasha Wolf Gallery and Bill Yates’ terrific series on The Sweetheart Skating Rink from the 1970’s was selected as a Critical Mass Top 50 Winner (as was Christine’s–more of their work to be featured this week). It bodes the questions, “Do photographs improve with time?” “It is a level playing field to stand along side work that has the patina of age?” “Do all photographs age well?” I don’t have the answers but I do know for me personally, that after years of working in black and white, then shifting to color, I am yearning to start shooting and seeing in black and white again. I also am appreciating looking at black and white photographs more than ever–and at photographs that show some age. Having attended Photo l.a. and Classic Photographs Los Angeles 2014 this weekend, I am keenly aware that the reverence for vintage photography is still a huge component of photographic sales. So this week on Lenscratch, we will feature portfolios that are at least 20- 30 years old. I also wanted to share an article by Jeff Gates along the same lines.

Last week I attended a seminar put on by the Los Angeles Chapter of the APA. Three gallerists, a curator, and a photographer/festival director were on the panel discussing how to navigate the fine art photo world. They were asked the question of silver gelatin vs pigment prints and all three gallerists said they were still drawn to the silver gelatin print first. They also stressed how important it was to have a darkroom background and an appreciation for craft and process. They noted that today we live in a world of images, not necessarily photographs. All points well taken (as a film shooter, must admit that I am biased) as many of my students, when they first come to class, have never made a print and aren’t yet involved in the craft of printing .

Then there is the whole subject of the journey of the photographer which is another discussion, but I thought I’d share this terrific article in the British Journal of Photography.

I don’t sit around and try to examine what I did before, how good I am now, and if I’m as good as before. In the earlier years of my life, a lot of people didn’t appreciate the work I did. I would sometimes offer to give my work to someone and they’d forget to take it. Now they pay. Usually when people have to pay, they respect it more.–Saul Leiter, 89

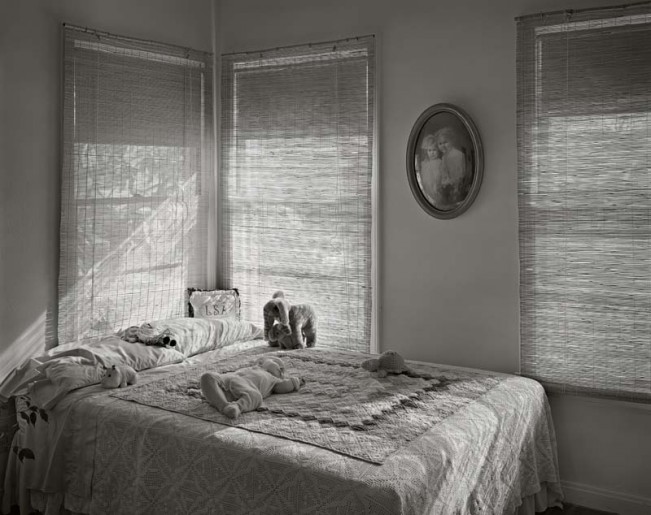

During this period of thinking about older work, I had the great pleasure of viewing the Abelardo Morell exhibition at The Getty. Not only was I struck by his pristine silver gelatin prints and his deep well of creativity, but I was struck by how much contemporary work has been inspired by his photographs. The Getty is an institution that rarely shows contemporary photography, instead shares work that has been vetted over time. The seminal exhibition, Where We Live: American Photographs from the Berman Collection, featuring the work of photographic greats such as Stephen Shore and Mitch Epstein, definitely pointed to our love of looking backwards and proving that vernacular photography seems to only get better with age.

Instead of just having an essay about my ruminations on looking backwards, I asked my friend Gordon Stettinius, who is now a publisher and gallery owner (Candela Books and Gallery), what his thoughts were on this subject. Gordon has championed photographers at the end of life, giving new exposure to decades old work. Here are his thoughts:

I am thinking that most photographic work does appreciate with time. Last week, I received a little over $120 dollars via Paypal. I had never had a positive balance in my Paypal account before and cannot remember why I even created it now. So, not knowing what else to do with that money, I was off to Ebay! And I spent my new found digital wealth on old photographs. I tried to spend it all on a Charles Gatewood 8″x10″ print of William S. Burroughs but that went for well over $200 and my last second poaching was backed only by a $125 bid. Chastened, I reeled myself back in and went for unknown artists, vernacular work. I bought an 8″x10″ of a botanist with his plantings, a “Boy with Rolling Hoop” cabinet card, an “unidentified woman sitting on car bumper- 1924″, a “50’s apartment homespun pin-up, partially nude”, and finally, I bought a “lot” of thirty-three vintage images because two or three of them caught my eye. I love old work. Obviously, I also respect known artists and I have dedicated much of my time to see that certain photographers get more recognition. BUT I do believe that almost any work that lasts, that was/is appreciated enough to be kept intact, will simply get better with time. It may be a romantic delusion but I feel the average snapshot of today will somehow manage to make us cry when we are creaky with age and juggling gauzy memories. That simple capable shot, has to have had something to it… a note taken about geography, culture, history of textiles, race, gender, fashion, architecture, signage, industry… something that will always hook someone comparatively once that moment is gone and thirty years have slipped by. The present will always compare curiously with the past.

If an original contemporary photograph is a novel and expansively articulated idea, then it will always splash down into our midst like a brilliant and hopped up wolverine into a suburban mall food court. And that screeching varmint of an idea will command attention, it will disrupt the natural order of things, it will fill out its speedo and speak three languages and dabble in kimchi fermentation… And then with a little more time, this spectacular incendiary photoklast will shed a little of its dynamic appeal, settle in to its new routine, maybe start dating the cashier over at Sbarro. But sadly, most ideas and images do not receive the aesthetic stigmata that the artworld gatekeepers will etch upon certain ‘chosen’ work. Most work, most photography, falls into the ‘capable and dedicated’ realm. We keep making it, even if it isn’t brilliant at every turn. And the fresh bloody art newness of our recent work will always require our unconditional love. We keep moving (hopefully) though and the next project unseats the last one and so it goes even as our culturally broadcast highlights are few and far between. Even as the creators cannot be much trusted to see clearly right away, neither can those with the formally weighted opinions be completely believed. What distinguishes the good work from the celebrated work often has as much to do with synergy and being in the right time and place as it does anything else. Sometimes a generous temporal distance between creation and recognition is enough to rouse interest in something, some curious aspect, that missed catching the wave of adulation back in the day.

Since becoming a gallerist, I have been trying to peel back the veil on the contemporary art market and to understand the vagaries of art as business, promotion and collectibility and the role that narrative plays in the trajectory of artwork. I have been trying to learn these inscrutable artworld mechanics because my role now is to advocate for certain artists in an attempt to help them gain exposure and income, so that they might carry on. My goal is pretty simple but the means by which I get there is part polish and part pyrotechnics and part hard-earned experience. I find that when I ‘believe’ in something then the whole process of advocating for that work feels okay to me. It feels pretty good to me actually. I wish I could do more for more people. But we do what we can do, and this gallery and others like it, we are all part of a hive mind tending to our visual heritage like so many frogs in so many wells. We place a lot of value on work today and because we do, because we cherish ideas and expressions, we hope, in turn, that our own ideas and artwork will continue to be honored. A psychologist might suggest we are busy projecting value upon the past so that our present, soon past, will hopefully have a like value one day… Maybe… But I do love older work for reasons above and beyond the original intent of the original maker. I love the nature of time and fragility layered over the unique significance of the artists craft.

Later this week we will be highlighting another photographer that Gordon is championing, Louis Draper.

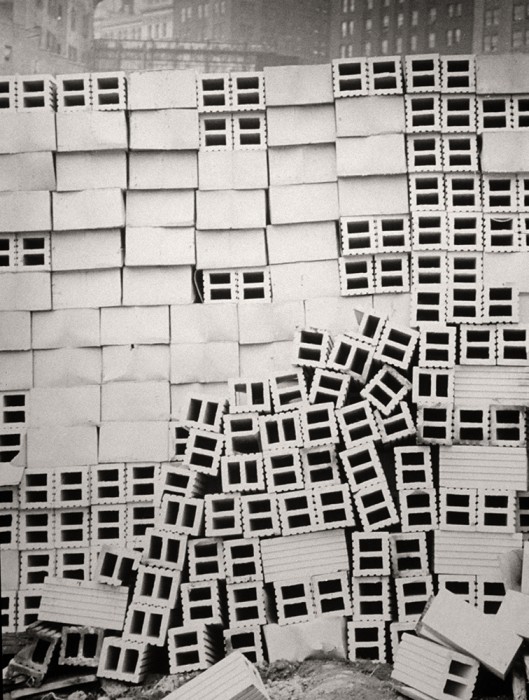

“Candela Books + Gallery is presenting the first retrospective exhibition of the mid-century African-American photographer, Louis Draper (1935-2002). Retrospective will showcase over 40 photographs spanning Draper’s career, from the late 1950s to 1990s. Primarily a street photographer, Draper’s archive has revealed an incredible range of artistic skill, including portraiture and abstraction, which will all be highlighted in the exhibition.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

2023 in the Rear View MirrorDecember 31st, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Staff Favorite ThingsDecember 30th, 2023

-

Inner Vision: Photography by Blind Artists: The Heart of Photography by Douglas McCullohDecember 17th, 2023

-

Black Women Photographers : Community At The CoreNovember 16th, 2023