Notes from a Curator: Photographic Posturing

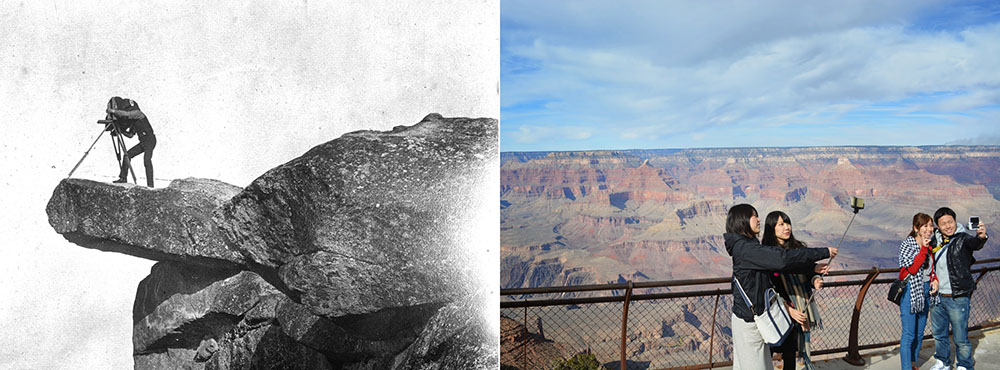

William Henry Jackson on Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park and Tourists at the Grand Canyon today with selfie sticks and digital cameras. (Sources: History Colorado-20102239 and https://selfieworldblog.wordpress.com/2015/10/15/selfies-home-in-social-media/)

Curator Lisa Volpe of the Wichita Art Museum will be sharing photographic essays on Lenscratch from time to time to give us an insight into what a curator is considering, and help illuminate the nuances of photography that effect our image making. Today, Lisa discusses Photographic Posturing and how our cameras impact our photographs beyond the lens.

Have you seen this TED talk? Amy Cuddy from the Harvard Business School studies body posture as a form of non-verbal communication. She discusses how our physical position shapes our opinion of others and ourselves—how it changes the messages we are sending. Cuddy’s talk had me thinking a lot about photography, another form of non-verbal communication. How does a photographer’s posture shape the images they are creating? How is photographic posture evolving in the age of digital imagery?

Unknown Photographer, H.E. French using a box camera, 1909. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (Image source: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3a36038)

Leica Advertisement, 1926. (Image source: http://www.loeildelaphotographie.com/2014/02/17/article/24165/100-years-of-leica-photography/)

It’s not such a crazy question. Most books will tell you that 1925 was a turning point in photographic history. That was the year the first successful 35mm camera, the Leica I, was released. This new, hand-held photographic technology ushered in an aesthetic revolution. No longer awkwardly positioned under a heavy black cloth staring into ground glass, or down into a box, the camera became an extension of the photographer’s eye, allowing for the creation of a new photographic aesthetic filled with dramatic angles and views. A photographer’s artistic vision could roam in whatever direction their eyes could.

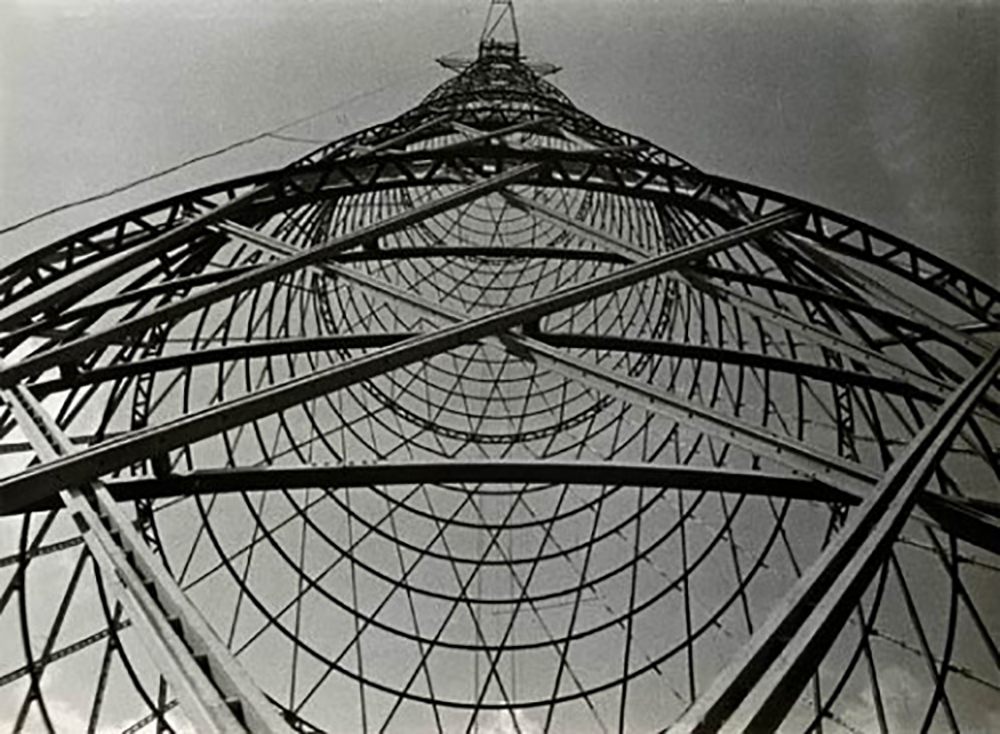

Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956), Suchov-Sendeturm (Shuchov transmission tower), 1929. Gelatin silver print, 5 13/16 x 8 7/8 in. © Rodchenko & Stepanova Archive, DACS 2010. (Image source: http://www.reframingphotography.com/resources/alexander-rodchenko)

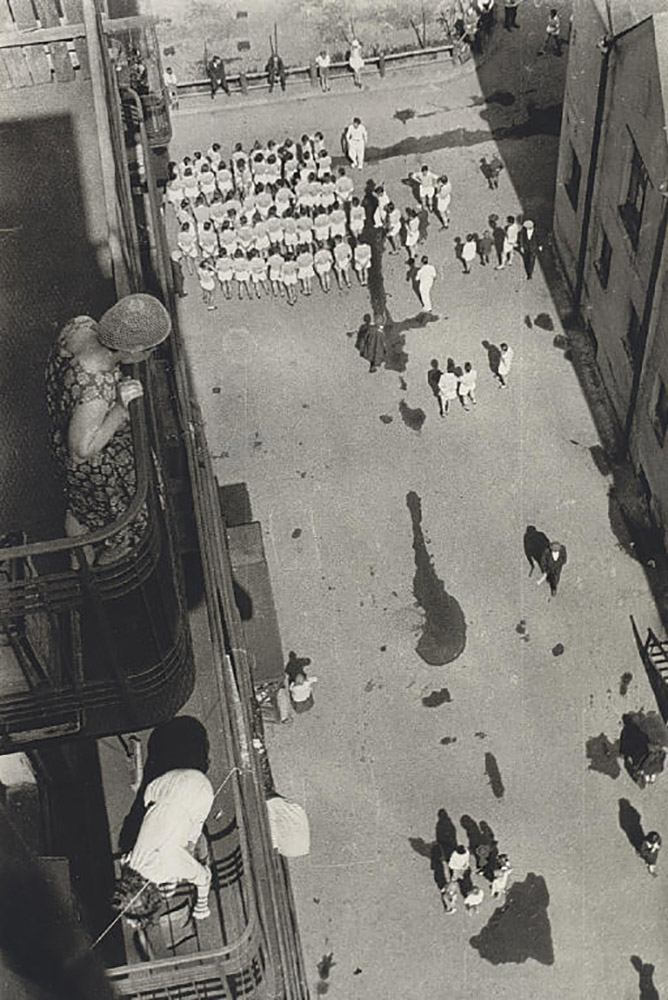

Russian photographer Alexander Rodchenko’s daring work demonstrates the new artistic possibilities unleashed when photographers were able to hold the camera up to their eye. Rodchenko captured soaring new buildings from low angles and public spaces from bird’s-eye views. He advised photographers to “take several different photographs of an object, from different places and positions as though looking it over.” He urged photographers to eliminate “old points-of-view,” especially that of “looking straight ahead.” In short, he advocated for new physical perspectives.

Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956), Assembling for a Demonstration, 1928. Gelatin silver print, 11 1/8 x 7½in. (Image source: http://monoskop.org/Alexander_Rodchenko)

Another familiar example of the link between posture and imagery is the twin lens camera with a waist level finder preferred by Diane Arbus. Arbus’s early photographs from the 1950s were created with a 35mm camera, and they don’t yet have the distinctive style one associates with her photographs.

Diane Arbus (1923-1971), Couple at a Dance, 1960. Gelatin silver print, 14 x 11 in. (Image source: https://onlineonly.christies.com/s/photographs-by-diane-arbus/a-couple-at-a-dance-nyc-1960-30/251)

It was in 1962 that she started to use a 2 ¼ camera and her distinctive approach truly emerged. Arbus celebrated the clarity and detail possible with her new camera and film, but it also changed her physical position and, therefore, her relationship to her subjects. The somewhat intrusive glare of the 35mm lens was no longer aggressively pointed outward. Instead, the posture required to operate a twin lens camera makes the photographer submissive—head down, arms close to the body. In essence, Arbus was putting her subjects in the position of power, allowing the “freaks and pariahs” (as Susan Sontag called them) to become equal collaborators in her photographic process. As Cuddy argues, in any interaction, we tend to compliment the other person’s non-verbal communication. Arbus’s subjects look at us, more than they are being looked at, thanks in part to the posture Arbus assumed.

Diane Arbus, The Junior Interstate Ballroom Dance Champions, Yonkers, NY, 1962. Gelatin silver print, 14 7/8 x 14 5/8 in. (Image source: http://www.sothebys.com/content/sothebys/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2015/photographs-n09405/lot.165.html)

Or, consider Cindy Sherman’s shutter-release method, which changed her physical position to the camera. Sherman’s images of various female personas emphasize the ways in which self-identity is often measured by ubiquitous pop culture images. Physically displaced from behind the camera to the space in front of the lens, Sherman embraces the role of photographic subject, a role that is inherently performative. As Roland Barthes notes, as soon as he feels himself “observed by the lens,” a transformation occurs. “I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image” (Camera Lucida, 10). For Sherman, a change in physical position was paired with a change in imagery. Stepping out from behind the camera meant abandoning her personal vision. In front of the lens, she transformed herself into the images of others.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #6, 1977. Gelatin silver print. 9 7/16 x 6 1/2 in. (Image source: http://nymag.com/anniversary/40th/culture/45773/)

There are clear echoes of Sherman’s work in the meteoric rise of the selfie, both in the posture of the photographer/subject and in the meaning of the imagery. It’s the digital age that ushered in the ubiquity of the selfie, thanks to the no-cost, instantaneous nature of the photographs, the presence of a camera on every cell phone, and the multiple social platforms for this public form of portraiture. According to Dr. Mariann Hardey of Durham University, this imagery is “about continuously rewriting yourself…it’s an aspect of performance.” Like Sherman’s work, selfies are all about transforming yourself into an image before the lens—object more than operator—as reality star and “selfie addict” Kim Kardashian’s images can attest.

Yet, even if people aren’t indulging in performative portraiture, most of the population is currently at arm’s length from their photographs. Tourists at the Grand Canyon, families in their living room, holidays, weddings, and sports, are now captured by a digital camera or cell phone held far away from the body. Most people stare at a screen rather than through a viewfinder. Photography, for most of the population, happens out there.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that as more and more people hold their cameras and phones away from them, contemporary art photographers steadfastly keep photography close—not only in posture but in subject. Artists hold their cameras to their eyes (or slip behind the ground glass of a large format camera—another intriguing physical relationship). Photographing in this way isn’t strictly a necessity from a technological standpoint (though you can argue for the aesthetic merits of the approach). Instead, it is done as a matter of pride, or a labor of love, or because of some other emotional motivation. The physical proximity seems to cultivate a sense of intimacy in the final images.

2015 was a year marked by a notable rise in the number of photographic projects that are deeply personal in nature. As Aline Smithson writes in Lenscratch’s “Our Favorite Things” wrap-up of 2015, “We are creating projects about ourselves, our identities, our families, using the camera to capture our interior worlds rather than just the outside world or what’s reflected in our viewfinders.” Smithson’s association of project focus and the physical nature of photography is especially germane. I can’t help but wonder if those projects have a lot to do with the posture the photographers assume, in comparison to the rest of the photo-taking world. As Amy Cuddy notes in her talk, the messages we communicate and the ways we understand ourselves are influenced by our own posture.

Lisa Volpe is the Curator at the Wichita Art Museum. She previously held several positions in the photography department at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (SBMA). She served as a the Ralph M. Parsons Curatorial Fellow for the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and as the Case Western University Fellow in the photography department at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Volpe lectured in the art history department at the University of California, Santa Barbara and held an adjunct professorial position at the Brooks Institute. She contributed to and helped organize several collaborative exhibitions and publications including John Divola: As Far As I could Get, a collaboration between SBMA, LACMA, and the Pomona College Museum of Art; and Chaotic Harmony: Contemporary Korean Photography a collaboration between the Houston Museum of Fine Arts and SBMA.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025