Real American Places: Edward Weston and Leaves of Grass

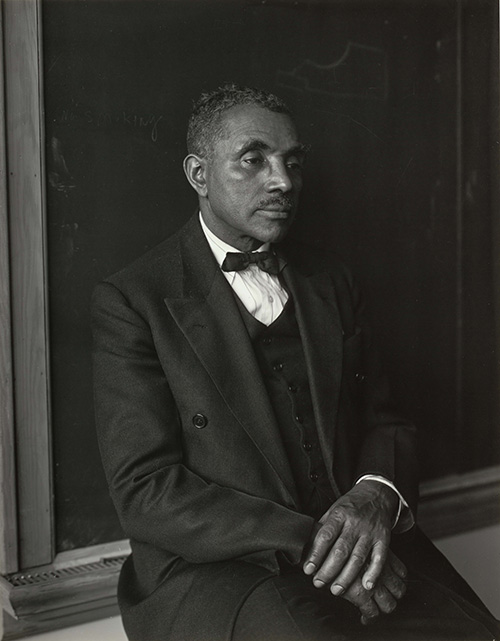

Mr. Brown Jones, Athens, Georgia, 1941 Gelatin silver print Photograph by Edward Weston The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens ©1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California has opened an exhibition that considers a rich dialogue between two iconic figures in American culture: the renowned photographer Edward Weston (1886–1958) and poet Walt Whitman (1819–1892). Real American Places: Edward Weston and Leaves of Grass in the Chandler Wing of the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art runs through March 20, 2017. The exhibition is curated by Jennifer Watts, The Huntington’s curator of photography, and James Glisson, Bradford and Christine Mishler Assistant Curator of American Art.

This is not an ordinary exhibition honoring the work of a master photographer and poet, but instead the curators go deeper to discover the realities of Weston’s assignment, his unsung collaborator, wife Charis Wilson, and the pivotal time in history in which the work was made. In conjunction with the exhibition, filmmaker Aric Allen has created a short film to accompany the photographs. An essay by curator Jennifer Watts follows.

The 25 photographs included in the exhibition illuminate an understudied chapter of the celebrated photographer’s career. In 1941, the Limited Editions Book Club approached Weston to collaborate on a deluxe edition of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, which Whitman published in five ever-larger editions during his lifetime. The publisher’s ambition was to capture “the real American faces and the real American places” that defined Whitman’s epic work. Weston eagerly accepted the assignment, and, from 1941–42—on the eve of the United States’ involvement in World War II—he set out with his wife, Charis Wilson, on a cross-country trip that yielded a group of negatives marking the culmination of an extraordinarily creative and prolific period in his career. Most of the images were made with a large, 8 × 10 camera and captured a wide-ranging landscape and set of experiences across 24,000 miles, from California through the Southwest and South, up to New England and Maine. The announcement of Pearl Harbor’s bombing in Dec. 1941 caused Weston and Wilson to abort their trip and hurriedly retrace their route to California.

White Sands, New Mexico, 1941 Gelatin silver print Photograph by Edward Weston The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens ©1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

While Weston believed the photographs to be some of his best, the resulting Limited Editions publication, which is on view in the exhibition, proved a failure on many fronts. The pages were tinted a sickly green, said Watts, and, likewise, “Weston’s elegant black and white pictures were surrounded by a mint green border, much to the photographer’s disgust. The final indignity came with the pairing of Weston’s pictures with specific lines in Whitman’s text, a decision Weston rightly felt undermined his own vision of America.” As a result, the photographs from the Leaves of Grass project have been relegated to footnote status in Weston’s oeuvre.

Mr. and Mrs. Fry of Burnet, Texas, 1941 Gelatin silver print Photograph by Edward Weston The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens ©1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

But, said Watts, “this is an important body of work that has been unjustly overlooked and clearly deserves its due. There are masterpieces in the mix, every bit the equal of Weston’s best work. How could it be otherwise? The Whitman effort came after a lifetime of honing a prodigious talent. The challenges of the project notwithstanding, Weston’s mastery shines brilliantly through.”

Though Weston deemed the book a failure, he considered the photographs an unqualified success. In 1944, he selected and printed 500 photographs for The Huntington as a gift to establish the most significant institutional legacy of his lifetime. Of this remarkable group, 90—almost one-fifth the total—are pictures he took for the Whitman project.

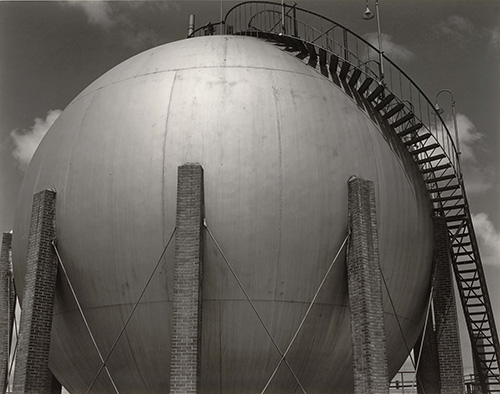

Gulf Oil, Port Arthur, Texas, 1941 Gelatin silver print Photograph by Edward Weston The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens ©1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

In 2003, The Huntington acquired Charis Wilson’s typescript diary recounting every aspect of the journey, which is on view in The Huntington’s Library Main Exhibition Hall, as well as documentation detailing the contentious creative wrangling between Weston and the Limited Editions publishers, both of which significantly informed the research for this exhibition. The Library’s manuscript and rare book holdings also include a number of original Whitman items, including a sampling of Whitman’s draft pages and his handwritten corrections on printed proofs for Leaves of Grass. Some of those pages will be on display in the exhibition.

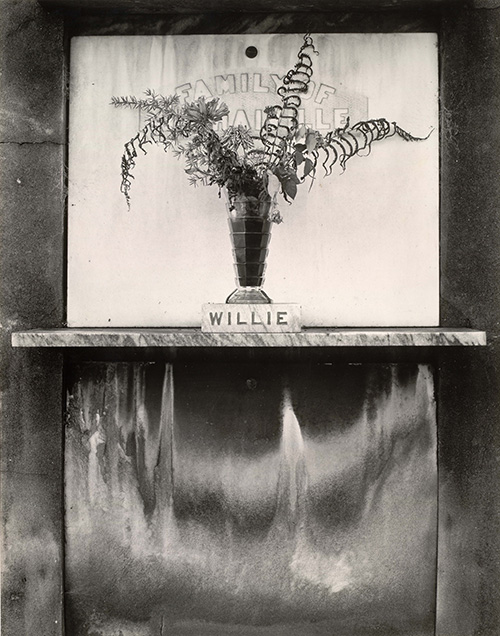

New Orleans, 1941 Gelatin silver print Photograph by Edward Weston The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens ©1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

The Brooklyn Bridge, 1941 Gelatin silver print Photograph by Edward Weston The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens ©1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Jennifer A. Watts, Curator of Photography, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens shares this essay on the exhibition:

On the evening of May 27, 1941, photographer Edward Weston and his wife, Charis Wilson, ate a quiet supper with friends and listened to President Franklin D. Roosevelt make a radio address. “I have tonight issued a proclamation that an unlimited national emergency

exists,” the president announced. As the Nazis continued to overtake Europe, Roosevelt warned that America needed to shore up its military readiness in anticipation of being called to support Britain and its allies.

Edward and Charis were set to leave the next morning from Los Angeles on a cross-country trip. A brand new eight-cylinder Ford (nicknamed “Walt”) sat loaded with gear: an 8×10-inch view camera, a Cooke Triple Convertible Lens, film negatives, a typewriter,

camping equipment, and cans of food. Preparations had taken weeks. Armed with letters of introduction from influential friends—and hundreds of contacts stretching from California to New York—the two planned to take a southern route before heading up to

New England and driving back six months later via a northern path. The assignment? To create a visual portrait of America for a deluxe edition of Walt Whitman’s iconic poetry collection, Leaves of Grass.

President Roosevelt’s sober message signaled turbulent times. While the nation veered ever closer to World War II, Weston faced a difficult journey of his own. With more than three decades of accolades and awards behind him, the 55-year-old photographer stood

at the pinnacle of his career. When he accepted the invitation from George Macy, publisher of the Limited Editions Club, to photograph “the real American faces and the real American places” that symbolized Leaves of Grass, Weston saw it as a tantalizing opportunity to

make a truly significant body of work.

Edward and Charis left Los Angeles as scheduled. Following Route 91 to Barstow and then east into the Mojave Desert felt as familiar, Charis wrote, as a “repeating dream.” The two had only recently completed another major road trip after Weston’s 1937 receipt of a

prestigious Guggenheim grant (the first awarded to a photographer). The resulting book, California and the West—with pictures by Edward and text by Charis—had appeared in 1940 to great acclaim. With the Whitman commission, the artist relished the opportunity

to expand his geographical boundaries and push yet further a visual investigation of landscape, continuing his “mass observation in seeing,” as Weston described it.

Born and raised in Illinois, Weston had moved from Chicago to Los Angeles in 1906. He married and opened a portrait studio in Tropico (now part of Glendale) to support his wife Flora and four young boys. Outside of his day job, he made dreamy, soft-focus photographs featuring dancers, his family, female nudes, and other evocative subjects that won Real American Places: Edward Weston & Leaves of Grass prizes at top Pictorialist salons. A meeting in New York in 1922 with Alfred Stieglitz, art photography’s éminence grise, as well as three transformative years in Mexico beginning in 1923, led to the emergence of a sharp-focused aesthetic and prints of radiant depth.

By the time Weston relocated to the bohemian coastal colony of Carmel in 1929, his reputation as a leading photographer of the West Coast school was sealed. There he fell in love with Charis Wilson, the beautiful, self-possessed daughter of famed novelist Harry Leon Wilson, and the two built a simple home and studio named Wildcat Hill.

The Whitman project began straightforwardly enough. In 1940, Macy asked 50 of the nation’s foremost literary critics to list the ten most influential American books; Leaves of Grass appeared near the top. Given the volatile global political climate, many saw Whitman’s collection as a full-throated tribute to democratic ideals. The Limited Editions Club had issued Leaves of Grass in 1929, but Macy called that edition a failure because of its restrained and delicate design. This time he sought a quintessentially American photographer to illustrate—an expectation that became the project’s stumbling block—a quintessentially American work.

As Charis and Edward headed east toward their first significant stop—Boulder City, Nevada, and its massive hydroelectric dam—Charis was behind the wheel, since Edward had never learned to drive. Their itinerary took advantage of cheap lodging and the hospitality

of acquaintances. Despite early fee negotiations, Macy remained firm on $1,000 to cover six months of travel and six months of printing, plus supplies. Weston’s initial insistence that he needed to see the full sweep of America took Macy aback. The publisher thought that the “melting pot” nature of Southern California would provide a wealth of “American types” from which Weston could choose, an assertion the photographer found ludicrous. Despite the early disputes that augured bigger challenges ahead, Weston told Macy, “I fully expect to do the best work of my life in the coming year.”

Once at Boulder (now Hoover) Dam, Edward immediately got to work. Over the three days that he and Charis toured the site, he made 18 negatives, a prolific output for a photographer who created precise compositions on the ground glass and never cropped or significantly altered his final prints. All in all, Weston found it a “tremendous experience,” he wrote to his sister May.

Indeed, for Weston—whose work in recent years had been tied closely with that of Ansel Adams and other California artists focused on the natural world—the trip’s industrial and architectural sites excited him the most. The Westons stayed an extra three days in Port Arthur, Texas, where Edward made more than a dozen pictures of gleaming Gulf Oil storage tanks that appear gargantuan and otherworldly, like spacecraft touched down to earth. At the Armco Steel Mill in Middletown, Ohio, a place he had visited in 1922, Edward pointed his camera up to the sky for a series focused on concrete smokestacks and intersecting power lines. Charis claimed they would have explored more such places, were it not for security restrictions.

By August, when the pair reached New Orleans, a number of problems had reached a slow boil. Four months had passed, and they had covered thousands of miles through Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and now into the South. En route, the partnership had taken a painful turn. Though 28 years his junior, Charis—talented in her own right—considered herself Edward’s equal on the project. She had been typing up each day’s events and envisioned publishing a book similar to California and the West. The realization began to dawn on her that Edward did not see her contributions as equivalent to his own. In the midst of a disagreement about whether they should venture off the beaten path, he hissed, “It’s my grant.”

Weston had been sending negatives back to his son Brett in California to develop, and the routine worked well. When he sent a progress report to Macy, the publisher fired back a letter stating that some of the subjects Weston mentioned gave Macy a real “fright.” He asked the photographer to send sample pictures straight away.

Thus came to the surface the fundamental misunderstanding that dogged the project from its inception to the bitter end: how the publisher and Weston construed the word illustration in relation to the book. The artist interpreted it in a metaphorical sense, whereas

Macy wanted to tie Weston’s photographs to specific lines in Whitman’s text. “I appear to have fastened onto an idea that you haven’t,” Weston replied to Macy. “[That] the pictures as a whole were to embody the vision of America that Whitman had . . . The fact is, illustrating specific lines in the poems would—to my mind—be too easy and get you no where.”

The book’s designer, Merle Armitage, soon entered the fray. A self-described “impresario,” Armitage was a longtime champion of Weston and a bellicose friend. Armitage sent Macy a screed. He took the publisher to task for his literal-mindedness with regard to two accomplished artists working generations apart. He reminded Macy that it was the timeless spirit (rather than the specificity) of Whitman’s poetry that made Weston the perfect complementary choice. “Let us keep before us the reminder that ‘the strongest and sweetest songs remain to be sung,’” he wrote. “This quotation by Whitman is the very essence of his meaning, it was the future of America which interested him equally if not more than its present.” For the time being, Macy demurred. He avowed that the project had room enough to satisfy Weston’s “cosmic America” as well as the publisher’s more down-to-earth concerns.

Weston kept working in spite of the testy exchange. He considered New Orleans and its Deep South environs a high point of the trip. He and Charis made the acquaintance of fellow photographer Clarence John Laughlin, who squired them to his favorite haunts,including Woodlawn Plantation, a former architectural beauty ravaged by the weight of its past. Weston made a disquieting photograph of an automobile parked between the home’s Greek Revival columns, looking as if it had simply run out of gas.

The Westons were captivated by places that seemed quirky, strange, or exotic to a couple of Californians, like a forest of glittering trees made of glass jars—a “bottle farm”—created byan Ohio eccentric named Winter Zellar (Zero) Swartsel, and New Orleans’ above-ground cemeteries, with their water-stained vaults. As they headed north to New York and then into Maine, the two stayed with friends and fellow artists who recommended local sites. Famed photographer and Precisionist painter Charles Sheeler showed Weston the churches and barns of the Connecticut countryside. On a different occasion, a day trip out to Whitman’s birthplace on Montauk, Long Island, yielded nothing. Weston would be satisfied, however, with a picture he made in Brooklyn, an obvious bard locale, showing the famed bridge in the background and Manhattan peeking through.

And what of the “faces” that Weston had agreed to make? In spite (or more likely because) of his four decades working as a portraitist, the ratio of people to places is proportionally small. Weston took this one aspect of the job quite literally, searching for “types”: Yaqui Indians, a Tennessee farmer, some homespun Texans, two African-American men. The racial realities of Jim Crow America form powerful through lines in Charis’s journal entries. She records a comment from one Texan about “Negroes knowing their place” and mentions segregated drinking fountains at the Gulf Oil plant. Migrant sharecroppers found shelter at dilapidated Woodlawn, using the plantation’s doors as firewood to cook and keep warm. A portrait of Brown Jones, made in a classroom in Athens, Georgia, is a somber study of the cook and choirmaster dressed in his Sunday best. An alternate view shows Jones looking forthrightly at the camera, his expression open and unguarded. No pictures of African Americans were included in the book.

While Edward and Charis relaxed one December afternoon at a Delaware home, a butler burst in to announce that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. Charis had been plotting a Midwest route back to California to avoid the worst winter weather. That plan was instantly jettisoned. The two left for Georgia the next morning to retrace their southern route back to Los Angeles. Charis hoped to linger a bit on the drive, but Edward was in a rush. He knew that submarines were patrolling up and down the coast; he also feared possible enlistment for his four boys. They arrived in Carmel on January 20, 1942, some eight months, 24 states, and 20,000 miles later.

Weston immediately set to work sorting and selecting the 800 negatives he had made on the trip. In late March, he sent 70 prints to Macy, who would ultimately choose 49. The publisher had fired Armitage as the book’s designer and had decided—all protests to the contrary—to pair the pictures with lines from Whitman’s text. Macy informed a horrified Weston that the images would be printed on glossy paper bordered by a green mat. The book was rushed into production, and Weston never saw the proofs. He presented a copy to his friends Sally and David McAlpin with the inscription: “No apologies for the illustrations, but for their presentation, my tears.”

Though Weston deemed the book a failure, he considered the photographs an unqualified success. In 1944, he selected and printed 500 photographs for The Huntington Library as a gift to establish the most significant institutional legacy of his lifetime. Of this remarkable group, 90—almost one-fifth of the total—are from the Whitman project.

What to make of the photographs produced for this contentious commission near the end of Weston’s career? The best of the group build on subjects that Weston already knew and loved: the industrial sites of Middletown steel; the broad expanse of western desert, with its confounding sense of scale; New Orleans graves flattened out like Point Lobos tide pools. With other pictures, one can sense his frustration, which Charis noted at times, especially when he defaulted to “illustration mode.” Yet there are masterpieces in the mix, every bit the equal of Weston’s best work. How could it be otherwise? The Whitman effort came after a lifetime of honing a prodigious talent. The challenges of the project notwithstanding, Weston’s mastery shines brilliantly through.-Jennifer A. Watts, Curator of Photography, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Dawn Roe: Super|NaturalJanuary 4th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

The Aline Smithson Next Generation Award: Emilene OrozcoNovember 21st, 2025